I am a Texas Rangers fan . . .

I looked like a Rangers diehard, right down to the vintage baseball cap (the superior 1972–1985 model, with the red bill and the block T). But I had a dirty secret. Once a Rangers-mad kid, I’d bailed on the team long before its “claw and antlers” renaissance. I still rooted for the Cowboys, who had won three Super Bowls in my four years of high school. In the same period, the Mavericks had been operatically bad, which, perversely, bound me to them for life. (You could score loads of autographs after the games: “Right here, Mr. Mashburn!”) But the Rangers? How to explain what had made them, for a kid coming of age in the early nineties, so uncool?

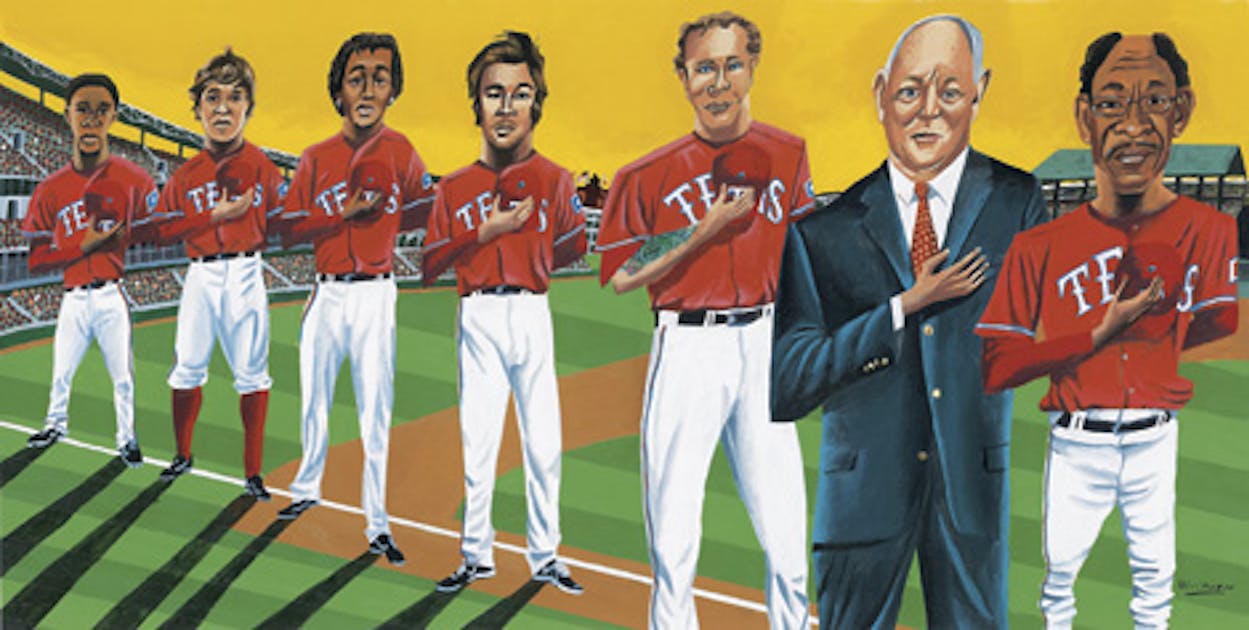

First, the old Rangers were not a good baseball team. The only memorable book written about them is called Seasons in Hell. Around the country, mentioning you were a Rangers fan typically solicited . . . nothing. But it was an unsatisfying kind of loserdom. Look at some of the names that percolated up through the franchise over the years: Mark Teixeira, Alex Rodriguez, Iván “Pudge” Rodríguez, Juan González, Sammy Sosa, Kevin Brown, Kenny Rogers, Rubén Sierra, Julio Franco, and Nolan Ryan—not to mention Jeff Burroughs, Al Oliver, Fergie Jenkins, Gaylord Perry, and Bobby Bonds. The Rangers had great talent, and they wasted it. They were doomed to be what pro-wrestling promoters call a mid-carder, a nice-enough team that would contend for second or third place in the AL West. “Not horrible,” said one of the team’s new owners. “Just kind of there.”

The culture of the franchise didn’t help either. Arlington was an absurdly friendly place, full of kind men who tucked polo shirts into khaki shorts. “If a player ever got booed in Texas,” Al Oliver says, “it was his fault.” As a teenager, I had my own growing anxieties about Dallas–Fort Worth life. And that friendliness—that sunny contentment as the world passed by—was just the kind of thing I was anxious about. I left Texas behind, and with it, the Rangers.

Now in my thirties, I had returned. I had become exactly the kind of sports fan I hate: a bandwagon-riding poseur who waits for a team to win and then shells out a few hundred dollars for the best (obstructed-view) seat in the house. Jeff Francoeur, a former Rangers outfielder who is now with the Royals, told me a story: On Sundays this past fall, he watched fans filing out of Cowboys Stadium, which sits across from the ballpark. These fans would walk a few feet and then shed their Cowboys jersey for a Rangers jersey underneath, molting like the North Texas cicada. I laughed. But deep down, I knew that jersey-changer was me.

No matter. These Rangers made coming back easy. The team’s culture was one of self-improvement, redemption, and recovery. After his cocaine revelation, Washington repented loudly and profanely (“I f—ed up,” he told a newspaper columnist). Left fielder Josh Hamilton, a former crack addict, was leading a national Christian revival tour. The team’s number two starter was “straight edge,” a salesman for an abstinent life. This kind of stuff is not uncommon in sports. But the Rangers were so open about it that it had become a mantra. The Rangers were an AA meeting in spikes.

I am a Texas Rangers fan . . .

The lethargic sensibility that so offended me had changed too. Jim Sundberg, a talented catcher who started playing Arlington in 1974 and is now a team executive, imagines an intensity scale that ranges from one to ten. Today’s Rangers? “We’re at an eight,” he says. And what about the old Rangers? “Maybe a two.” The transformation, he explains, was due to Nolan Ryan, who was sitting on the front row at my right. Ryan joined the Rangers as the team president in 2008 and then, last fall, bought the club with several partners. Ryan already had a highway in Arlington and a field at spring training named after him; like no other Ranger, he seemed to radiate legitimacy. “People in Texas agree with everything that comes out of his mouth,” says second baseman Ian Kinsler. George W. Bush impishly observed that the team had tapped Ryan to throw out the first pitch in game three of the series. The former leader of the free world would have to wait till game four.

I am a Texas Rangers fan . . .

Yes, they looked like the same old Rangers that October night, letting a young pitcher for the San Francisco Giants named Bumgarner and a stingy home plate umpire tie them in knots. The following night, in game five—I’d moved out from behind the post and into the upper deck—they got only three hits and lost the Series. We fans stayed for a while, chanting, “Let’s go, Rangers!” while the Giants celebrated. Something significant had happened: The Rangers had set themselves up to be contenders for many years to come. They had finally made their mark on baseball—and, well, on me. After rediscovering them, I set out with the zeal of a convert to find out just what it is that makes them tick. To write a Boys of Summer treatment for a team that never, ever deserved one. In turn, they rewarded old and new fans alike by starting 2011 as if the previous season had never ended. So yell it out with Chuck Morgan: Ladies and gentlemen, your (profoundly interesting, oddly moving) Texas Rangers!

***

Ted Williams was the first manager of the Rangers. He lasted all of one season in Arlington. “He’d take off his hat and scratch his head and mumble words you never heard before,” says Dick Billings, who played catcher for the Rangers from 1972 to 1974. “He liked the barbecue and the fishing. That’s about it. He wanted to get out of there.”

Williams liked to instruct his batters to hit the top of the baseball early in the game and the bottom of the ball in the late innings, just as he had as a player. “We’d look at each other and say, ‘You gotta be kidding me. I’m lucky to hit any part of the ball,’” Billings recalls.

I ask Billings if the ’72 Rangers ever dared to dream about going to the World Series. He begins to laugh. “We weren’t under any grand delusions. We were thinking, ‘I hope we hang around long enough to get our pensions!’”

People like to talk—occasionally smirk—at the way Ron Washington talks. There was the famous Washington quote—“That’s the way baseball go”—that turned up on a T-shirt. One Dallas sports columnist went so far as to call his way of speaking “E-Ron-ics.” When I sidle up to Washington’s daily press conferences at spring training, in Arizona, I find them as stubbornly data-free as they appear in the sports pages. The Rangers are trying to stay healthy, taking it one day at a time—name a cliché. But a funny thing happens when you survey Rangers players. You realize that talking isn’t Coach Wash’s weakness; it is his unappreciated genius. Through Washington’s mouth, the reinvention of the franchise began.

Washington was born in the Ninth Ward of New Orleans, in 1952. He had nine brothers and sisters. “Yes, I lived in the projects,” he tells me. “And after we got out of the projects, we lived in neighborhoods. But I was able to play baseball, which is all I wanted to do anyway.”

Listen closely to Washington and you sense he’s underplaying the roughness of his childhood, taking some heat off his fastball, as it were. Washington hurt his knees in the minor leagues in 1978 and was only a marginal player in the majors. The Twins, his second of five teams, released him in 1987, just before they won the World Series. He became a well-regarded coach with Oakland (he makes a cameo in Michael Lewis’s classic book Moneyball). The A’s interviewed him three times for their manager’s job but always gave it to someone else. Washington was a ripe 54 years old when he came to Texas, in 2007.

The Washington who showed up in Arlington, then, was a baseball lifer who had a deep familiarity with failure and an abiding appreciation of fate. I ask Darrell Miller, who’s working with Washington to create a baseball program for inner-city kids in New Orleans, to describe how he talks. Miller thinks a minute. Then he says, “It’s like it’s indirectly direct. He really gets to the core of the matter without hurting people’s feelings.” In other words, through Washington’s own travails—out of the projects but not quite into major league stardom—he has developed a way of talking that is frank but not cutting. His great skill is that he can take all the happiness and sadness that occurs during a 162-game season, whirl it through his head, and speak it in a way that keeps his team level.

“The first thing he did,” Rangers veteran Michael Young says one morning before practice, “is turn the clubhouse over to the players. He lets us police things in here.” Indeed, one of Washington’s favored tactics is saying nothing, removing himself from a situation where another manager might throw his weight around. Washington is always present, but he’s often silent. “The way you would sum up Wash,” says bench coach Jackie Moore, “is that he’d make a hell of a poker player.”

Silence is but one approach. During a game last season, Washington came up to Julio Borbon, the 25-year-old outfielder, and asked him to execute a squeeze play, a tricky maneuver that requires a batter to lay down a bunt while a runner charges home from third base. Wash was laughing when he made the request. “It was really peculiar,” Borbon says now, “but it was actually something that I liked.” Washington explains: “I was trying to get him to understand that this is no big deal. You just execute it because you’re capable of executing it.”

Another time last season, former catcher Matt Treanor came up with a runner at first and one out. Treanor misread a sign and tried to lay down a bunt. The ball went straight up in the air for an out. “Before Wash said what he wanted to say,” Treanor recalls, “he wanted to know what I was thinking.” Washington always wants to know what you’re thinking when you screw up. In Treanor’s case, Washington told him he wanted him to swing the bat, not bunt. Treanor came away thinking the manager had more confidence in him than he had previously known.

These are the kinds of delicate exchanges that sustain a team over a season. I ask Washington if the conversations are stored somewhere in his brain. “They are,” he says. “I couldn’t give them to you verbatim, but if a situation came up, they would pop into my head. ‘Matt was in that situation!’ Or ‘Julio was in that situation!’ I have so many young guys, I just try to explain to them what they have to do to make sure that next time they get it right.” ESPN’s Buster Olney remarked in the postseason that the Rangers had one of the loosest locker rooms he’d ever seen. By the time the team got to Yankee Stadium for the American League Championship Series, says Francoeur, “We were so relaxed, we didn’t give a crap where we were.”

The drug revelation last spring pushed Washington into a corner. He had tested positive for cocaine before the 2009 All-Star break, and the following March, the news broke on Sports Illustrated’s website. The team meeting that Washington called had such a strange vibe that pitcher C. J. Wilson thought the skipper was gravely ill. But after Washington spoke, Wilson stood up and told his teammates to treat the manager like family. Young said, “I’ve got his back. Anybody who doesn’t feel that way isn’t a Texas Ranger.” When Washington confessed to the media later, talking as bluntly as he ever had, he looked up and saw Young and other players standing in the back of the room in solidarity.

The manager who emerged from the scandal was even more verbally formidable. Before, Washington was tough; now he was incapable of being embarrassed. “If it so happened that I had to leave,” Washington tells me, “I would have found a job in baseball. Maybe not as a manager, but I’d be in the game.” His voice grows intense. “I’m one of the greatest infield instructors in baseball! That ain’t patting myself on the back—I’m good. And I’m one of the best third-base coaches in baseball! That’s not patting myself on the back—I’m pretty good.”

At spring training, Washington often throws batting practice, and I saw him pretending to zip the ball by his hitters rather than serving up an easy pitch. “Just remember,” he barks at third baseman Chris Davis, “you hit when I let you hit.” A few days before, when Young talked to the press about his off-season dispute with management, Washington repaid Young’s earlier gesture by standing in the back of the room. “We know what kind of guy Wash is,” says reliever Darren O’Day, “and we know he gets the most out of us.”

Washington realizes that speaking the language of baseball players is his gift. “If they are making fun of me,” he says of his critics, “that’s their problem. I’m from New Orleans! I am who I am! The way I do it, it works.

“And if it takes ‘E-Ron-ics’ to do it,” he says, a smile appearing at the edge of his lips, “that’s just the way it is.” Now, then, is Ron Washington making himself perfectly clear?

***

In 1978 the stud outfielder Al “Scoop” Oliver got a call saying he’d been traded from Pittsburgh to Texas. In the hierarchy of seventies baseball, going from the “We Are Family” Pirates to the lowly Rangers must have felt like a demotion. “I didn’t know much about Texas,” Oliver says. “The first thing that came to mind was the assassination of Kennedy.”

Oliver was a gifted hitter, the perfect complement to Bobby Bonds and Richie Zisk. Oliver still holds the Rangers record for career batting average. He threw out a couple of runners from left field, and within weeks there was a sign hanging from the bleachers that read “Al’s Pals.” Oliver would run out to his position and he’d get so many ovations that it was almost embarrassing. Rangers fans, as noted, are absurdly nice.

Did Oliver and those seventies Rangers, I venture, ever talk about going to the World Series? “You asked me a question I’ve never been asked in twenty-six years,” Oliver says. “Did we ever talk about a World Series? I did! I was so confident that I really believed we could win.” He adds, “I think the media thought there was something wrong with me.”

The faithful follow Josh Hamilton everywhere. A big man with curly hair and a sleepy demeanor, Hamilton is the most famous Christian athlete in Texas, if not America—a magnet for the penitent. In Arizona I trail the reigning American League MVP one day after practice as he tries to walk from the field to the locker room. He follows the left-field line, and his fans shadow him on the other side of a chain-link fence. Some are wearing shirts and hats that feature the “claws” and “antlers,” two gestures that became a signature element of the team’s identity last year (the claw celebrates a hit, the antlers a play that shows off speed). He stops to say something to a teammate, and they jolt to a stop, their knees locking like subway riders. There are probably one hundred of them—young and elderly, autograph-seekers and truth-seekers, those who call him Josh and those who yell his nickname: “Hambone!”

Once, drugs and alcohol and the devil derailed Hamilton’s life. These days, there are new temptations. As one of Hamilton’s friends puts it, “If the enemy can’t get me to do wrong, he’ll get me to do right wrong.” Meaning, he’ll tempt Hamilton into doing seemingly good things—signing autographs for the faithful, say, and telling his redemption story and charging into outfield walls—but he’ll tempt him into doing them too much. This is the temptation that keeps Hamilton’s friends up at night.

Hamilton has a two-track professional career that veers between baseball and faith, except when the two meet, which these days is increasingly often. Hamilton and his wife, Katie, have become close with James and Betty Robison, the 67-year-old televangelists who run a ministry called LIFE Outreach International. They met when Hamilton appeared on their network to promote a book, and later he and Katie bought a home near the Robisons in Colleyville. Josh tells me, “God put us close to each other.” James says admiringly, “I’ve never seen two people that I’d describe as more fertile ground to grow seeds.”

Betty has become a member of the faithful. She puts on a number 32 jersey for every Rangers game. When her friend comes up to bat, she delivers an oration to the television: “Josh, peace on your feet. Joy in your heart. A smile on your face. And patience.” Though he had a well-publicized relapse in 2009, with embarrassing photos that wound up on Deadspin, the Robisons have little worry that Hamilton will use again. At a recent dinner, James ordered a bowl of mushrooms to go with his steak and offered some to the slugger. Hamilton asked the waiter if the mushrooms had been cooked in brandy. Yes, the waiter said. Hamilton pushed the bowl back across the table.

Hamilton’s teammates were so convinced of his sobriety that they’d forgotten how seriously he takes it. On September 25, after the Rangers clinched the division title in Oakland, Hamilton and Wilson, who also doesn’t drink, found themselves sitting outside the locker room while their teammates bathed one another in champagne (the Rangers switched to ginger ale celebrations for the playoffs). After the game Hamilton went into the stands to preach to the faithful.

This is the Robisons’ fear: that the slugger is taking on a spiritual workload that would make even well-staffed ministers balk. The Robisons know of what they speak. Their TV show, LIFE Today, airs worldwide; their Fort Worth office gets more than 1,500 prayer requests a day. But, James says, “I’m in no way the kind of figure that commands public attention like Josh.” The sight of the Yankees cowering before Hamilton in the playoffs (they intentionally walked him five times in six games) and of Hamilton praising God first at the postgame celebration took Joshmania to new heights. This spring, the two families went to Abuelo’s Mexican restaurant the Sunday before spring training began for a quiet dinner. When they tried to leave the restaurant, the faithful were waiting by the door.

During the off-season, the Hamiltons told Josh’s tale of redemption at a dizzying clip. They told it in Fort Worth. They flew to Chicago and spoke four times at a church. The faithful appeared there, thousands of people who wanted to touch Josh, talk to him, shake his hand. A few days later, he was hospitalized with pneumonia. “I tell everybody I saved a little old lady’s life by stealing it from her,” he says with a smile. After five feverish nights in the hospital, Hamilton awoke in his bed, he tells me, and “there was a girl nurse . . . I woke up and she was praying over me.” The nurse had been on a different floor when she said God called her to Josh’s room. Four weeks after he left the hospital, the Hamiltons were talking to the faithful in Lubbock at an event called Heart and Soul of Sports. It was Valentine’s Day.

Hamilton knows he has to put on the brakes. His pastors have repeated it over and over. Next off-season is going to be about family, Hamilton tells me. He’s thinking about making fewer appearances to tell his story, or maybe even none at all. After the first day of practice in Arizona, the Rangers provide him with a security guard to manage the crowds.

Hamilton is learning not to do right wrong on the baseball field too. Since joining the Rangers, his furious style of play—he made an amazing diving stab in game four of the World Series—has led to several stints on the disabled list. Last September 4, Hamilton crashed into a wall during a game in Minnesota and fractured two ribs. He said the injury felt like a “car wreck.”

“Right before he jumps into the wall—that’s when you hold your breath,” says general manager Jon Daniels, who just signed Hamilton to a two-year, $24 million contract. How, I ask James Robison, can Hamilton learn not to throw his body around so recklessly? “That kind of wisdom comes from above,” Robison says. Does he counsel Hamilton about running into walls? “Big time.”

But here again Hamilton worries about letting down the faithful. “Obviously I had to pray about it,” he says. “I feel like God gave me the ability and talent to play the game, and I don’t want to shortchange anybody who’s never seen me play before.”

Call it Josh Hamilton’s new temperance. He cannot speak to the faithful at every event. He cannot shake every hand. And, heaven help the Rangers, he cannot keep sprinting when he sees warning track dirt under his feet. As Betty says out loud before every at bat, “Patience.” “Now, if he stays healthy for one hundred and sixty-two games,” says James, sounding as if he’s making a prophecy, “there’s going to be something to see.”

***

My single favorite thing about the Rangers in the eighties was watching Charlie Hough get pulled from a game. The knuckleball king would stroll back to the dugout and, in full view of the KTVT cameras, smoke a Tareyton cigarette. It was another era of baseball.

Hough, it turns out, thought a fair bit about pitching in the World Series during his eleven strong seasons in Arlington. I jot that down but tell him I’m fascinated by his smoking, a gloriously anachronistic habit for a pro athlete. “I smoked two or three packs a day back then,” he says. Wow, I reply, suggesting that holding out for that postgame cigarette must have been tough. “Oh, no,” Charlie says. “I smoked every inning.”

C.J. Wilson and I are talking about writing: novels, screenplays, TV shows, all the ways in which words arrange themselves into art. “I love literature,” the left-hander says. “I love film. The creative narrative is something I can’t get enough of.” I’ve had lots of giddy conversations with writers, though never with one who has a fastball that touches 98 miles per hour. In a season when the Rangers supplied great copy to every sportswriter in the country, Wilson was hunched over a computer, trying to churn out his own.

In the post–Cliff Lee era, Wilson, who won fifteen games last season, is the Rangers’ number one starter. He’s also their ambassador to the world of letters. Last spring, Wilson tweeted at Carlton Cuse, one of the creators of Lost, just as the show was entering its final season. The two hit it off, and soon Cuse welcomed him into the Lost editing room, immersing Wilson in the creative energy of the show. (Yes, he liked the finale.)

After Lost ended and the Rangers lost the World Series, the two men resumed their collaboration over a series of dinners in Los Angeles. “We talk about everything,” Cuse tells me. “We talk about baseball, but that’s only a small part of it. We talk about writing, about the creative process. We talk about our lives.”

They also talk about Wilson becoming a TV writer some day. “Athletes get pigeonholed into being announcers,” Cuse says. “But I think C.J.’s more interested in the kind of things I do. It’s entirely within his capacity to become a really good writer or producer.”

Wilson looks the part of a Hollywood scribe. He arrived at our interview wearing dark sunglasses and a V-neck T-shirt. By age five or six, Wilson had used his mother’s typewriter in Huntington Beach, California, to produce a short story—“Prince Charming Gets the Chick and Rides Off on a Horse.” By late high school, he was a good ballplayer producing meandering prose—it was like (and this is Wilson’s metaphor) Tolkien cramming all that bad poetry into The Lord of the Rings. Wilson majored in screenwriting at Loyola Marymount, in Los Angeles, where he starred as a pitcher and hitter but decided “academia is not my style. I’d rather slug it out in the trenches.”

When he was fourteen, he became straight edge. A popular creed in Orange County’s punk scene, it means swearing off alcohol and drugs. “So why didn’t you ever try them?” Hamilton once asked him. Well, Wilson had an uncle with a drug problem and was scared straight without ever sampling the stuff himself. He now has the words “Straight Edge” tattooed on his side and three X’s—a kind of straight edge logo—sewn into his trademark blue glove. His life is “drug-free,” Wilson likes to say, “but it’s experience-rich.”

Wilson was a loner when he arrived in the Rangers’ minor league system, in 2001, with headphones on his ears and his nose buried in a novel. It was (again, Wilson’s metaphor) a Black Swan period: His mind was feeding feverishly on itself. After hurting his elbow in 2003, he had surgery and was out of baseball for eighteen months. So he got a job at Nordstrom to learn how to better converse with people. He got serious about photography. He had nearly drowned a couple of times while surfing, but he went back to Orange County and jumped off cliffs into the ocean. “It was, like, sketchy,” he says. “But I was like, ‘Hey, if I die, I die. Cool. At least I tried this.’”

By 2005 he was on the Rangers’ big-league squad and working on a novel that takes the form of the journal of a dead minor leaguer. “I couldn’t finish it,” he says. “There was too much of my DNA in it.” In 2009 he started a Twitter account with the handle @str8edge racer. Wilson, you see, also drives race cars. “The only hobby I pay attention to is the race car driving,” says Jon Daniels. “I don’t think he can get hurt writing a television show.”

On the mound, Wilson is a clever pitcher, with an excellent cut fastball and a host of breaking balls that eat up left-handers. He has carved out a role on the Rangers like the one Ball Four’s Jim Bouton played with the Yankees in the sixties. “I’m kind of part of it,” Wilson says of his team, “but I’m also an observer.” In 2008 it was Wilson who told ESPN.com that no one in the Rangers locker room was talking about the historic presidential election. When a teammate challenged him, Wilson defended his comment by writing on a message board that the average major leaguer “is relatively a douchebag.” Another former Ranger—Wilson won’t identify him—recognized the description and posted paper copies of the quote in each player’s locker.

“The reality is that at the time I wrote it, there was a guy on our team that was gambling on sports,” Wilson says. “This guy, I just didn’t have any respect for him. I was thinking, if this guy needed money, maybe he would bet on baseball. I didn’t see anything in his moral fiber that would stop him from doing that.”

The incident points out an interesting thing about Wilson. He embodies baseball’s ideal definition of morality: no drinking, no drugs, a monastic code that is literally tattooed on his body. But with his Twitter account and writerly predilection, Wilson has something baseball fears more than anything else: a restless mind. “You can never make everybody happy,” he tells me, “unless you’re doing things that are disingenuous.” Spoken like a true writer.

This role of being in baseball but also observing baseball has attuned him to the rhythms of the locker room. Two years ago the Rangers held a hazing event in which veterans each got to dress a rookie in a humiliating outfit. Most chose negligees and bikinis. Wilson got his rookie, the Dominican pitcher Pedro Strop, a six-foot-tall beaver costume. He figured it would give Strop, who might never make it back to the bigs, an ounce of dignity.

“I think right now,” Wilson tells me, “I could write commercials.” Before the season started, he and Cuse released a Funny or Die video that had Wilson “working out” by doing chores at Cuse’s house. He says he’ll pick up that baseball novel after his career is over. And there’s a semi-formed idea for a TV show about his friends back in California, a kind of straight edge Entourage. “I’m glad I went cliff jumping,” he says. “I’m glad I almost drowned. I will write about those experiences, and it will be interesting.”

***

Is this Oddibe? “Yes,” says a cautious voice from Hollywood, Florida. This is Oddibe McDowell—former number one draft pick and the subject of a beautiful 1985 Topps U.S. Olympic Team card, a towering figure on the late-eighties Rangers.

McDowell, who is a shocking 48 years old, was never a huge talker in the press. But he’s happy to take a few questions. Question one: What does he remember about hitting for the cycle on July 23, 1985? I tell him I was sitting with my parents in left field when he hit his climactic home run. “I couldn’t even tell you what inning it was. Or whether we won or lost the game.” (He hit the homer in the eighth, and the Rangers beat the Indians 8–4.)

Question two: Ever think about the Rangers’ being in the World Series? Here McDowell has total recall. “All the young arms we had and whatnot? Sure. I always thought of that.” It occurs to me that what I mistook as sunny contentment in Arlington was really quiet frustration, the pain of all those almost-great seasons. Of course the Rangers had as much determination as the Yankees or the Red Sox. They just needed the right guru to bring it out.

With his bald head and jolly girth, Nolan Ryan is the Buddha of the Rangers. You nearly always see the team’s CEO planted in the ballpark’s owner’s box, or else he’s lumbering around the offices with his “big ol’ hands and big ol’ accent”—the apt description from Jeff Francoeur, who, during the two months he played for Ryan, was moved to ask his boss for his autograph.

At spring training I find Ryan wearing cowboy boots and blue jeans and leaning on a chain-link fence. “It’s baseball,” he drawls, “but we’re also in the people business.” You could sketch out the resurrection of the franchise like this: The new owners gave the Rangers a payroll, Daniels provided the players, Washington the rudder, and Ryan the soul.

Ryan, who is 64, left his Georgetown home to join the Rangers in 2008. He had never been a major league executive. But his run as a forty-plus-year-old pitcher in Texas had given him untold cachet.

Just exactly what Ryan did is a little hard to describe. The first thing was just being there. His presence sent a message that the Rangers had a backstop of common sense, that they would no longer manage to do things like trade away Alex Rodriguez and still be on the hook for part of his salary. Outfielder David Murphy tells me he has gotten used to being around ex-ballplayers he once idolized, but with Ryan, “I joke that I feel like I need to salute him or stand at attention.”

Ryan set about trying to fix the Rangers’ historically dreadful pitching staff. This had a practical component: With Coach Mike Maddux, he challenged the prevailing wisdom that said pitchers should be coddled instead of asked to throw nine innings. As is customary with Ryan, there was also an emotional part. The Rangers’ home field has carried the mark of death for pitchers. The dimensions and jet stream mean more home runs, or else the weather is too hot—in either case, a free agent who signs with Texas hears he’ll add a run to his ERA.

But Ryan embraced the ballpark’s faults. “We should use the heat to our advantage,” he tells me. “That’s what I say to our guys. Get out in it. Know that it can be your friend. Emotionally and mentally, it whips that other team.” After brilliant seasons from Wilson, Colby Lewis, and Cliff Lee, the Rangers began the process of rebranding their humidity.

The pre-Ryan Rangers suffered from years of flip-flopping strategy; with Ryan, they have a plan. The day before I met him, he extended Daniels’s contract until 2015; key Daniels lieutenants Thad Levine and A. J. Preller were said to be next. He helped ease Chuck Greenberg out of the organization after the ownership group’s ebullient front man proved to be a pest. After a feeling-out period with Washington, Ryan extended his contract too. Asked why he hadn’t accepted Washington’s resignation in 2009, Ryan told the press, “Just because someone in your family makes a mistake doesn’t mean you stop loving them.”

This tendency to put baseball decisions in tender, emotional terms is a trademark of Ryan’s. He likes to talk about his feelings. He is Iron John by way of Casey Stengel. “I want to know what’s in somebody’s heart, what’s in their mind,” he says. When Ryan came to the Rangers, he was stunned to find his employees hypnotized by their smartphones. “You can’t even talk to somebody nowadays without them looking at their iPhone all the time because they hear it beeping,” Ryan says. Ryan considered banning smartphones from the team until he was informed that the Rangers have a sponsorship deal with Verizon. As we are talking, he sheepishly pulls out his BlackBerry and says he texts, reluctantly.

The communications snafu that rocked the Rangers this off-season was the Michael Young affair. Young is a Rangers elder, admired for hitting and selflessness. He moved from second to shortstop to make way for Alfonso Soriano, to third for Elvis Andrus, and, finally, to designated hitter and backup infielder when the team signed Adrian Beltre this off-season. But after the Rangers tried to trade him and eyed free agents that might take even his diminished role, Young blasted the club in the sports pages. “I’ve been misled and manipulated,” he huffed.

It was Ryan who called. “I wanted to reach out and say, ‘Let’s talk about what’s going on,’” Ryan recalls. “‘What you’re feeling. What your thoughts are.’ If our relationship isn’t right, it’s going to affect how we play and who we are.”

Who we are. It’s an oddly humane sentiment in the Moneyball era, where an eleven-year vet is only as valuable as his ultimate zone rating at third base. Ryan can afford to be a sweetheart, Daniels explains, tongue only sort of planted in cheek, because he never really has to be the team’s bad guy. Indeed, when Young showed up in Arizona this spring, he was furious at Daniels and utterly at peace with Ryan.

The Young episode aside, Ryan typically sticks to a high perch. Of the players’ clubhouse, Ryan says, “I’m a believer that that’s their sanctuary. Very few people should have access to it. I’m concerned with them, but I don’t try to be their friend.”

There’s a hint of sadness in his voice. Ryan tells me that what a retired ballplayer misses most about the game is his teammates, the sense of belonging, the locker room’s pirate spirit. “I’ve never found a replacement for the camaraderie in the clubhouse,” he says. “There’s a void there.” Nolan Ryan, the baseball Buddha, has filled it by trying to be a big ol’ mensch to everybody.

***

Did you know the Rangers planned three previous World Series in Arlington? Tom Schieffer, the team’s president in the nineties, remembers scheduling a party at the Dallas Museum of Art. Another at Six Flags. Probably something in Fort Worth. When you win your division, as the Rangers did in 1996, 1998, and 1999, you have to have a plan for a World Series. And when you subsequently win once in three playoff series against the Yankees, you quietly toss those plans in the trash.

The worst thing about a non–World Series is the tickets. Those have to be printed in advance with the home team’s logo. “I had seen Rangers World Series tickets before,” Schieffer says sadly. “I just never got to use them.”

We can’t leave the Rangers without reliving the single most important at bat in team history—which is, of course, the undressing of Alex Rodriguez, on October 22, 2010, during the ALCS. After that at bat, the Rangers mattered for the first time ever.

It was game six. The Rangers, up three games to two, led 6–1 in the top of the ninth. Dick Billings, the old catcher from the ’72 team, had plunked down a few thousand bucks for seats behind home plate, and he noticed him right away: A-Rod, the guy who wondered, “What am I in this for?” during his tenure in Texas, standing in the batter’s box. He was gonna be the last out.

When Chuck Morgan announced Rodriguez’s name, everyone in the stadium got it. The song “We Are the Champions” was already cued up. From about this moment forward, Daniels remembers almost nothing.

On the pitcher’s mound, Neftali Feliz bent down and took a deep breath. He threw a fastball for ball one. Then: strike one. And: strike two. The ballpark was in a fury now, those nice Rangers fans that had once put up a sign for Al Oliver finally giving in to their passions. At third base, Young found himself staring into the crowd; he’d never heard any major league stadium this loud. First baseman Mitch Moreland caught Ian Kinsler at second with a huge grin on his face.

Kinsler was looking for the sign. Feliz had thrown nothing but fastballs that inning, and Kinsler saw catcher Bengie Molina show two fingers: slider. And then he saw Molina center his glove and stick it out, which meant, “Throw it for a strike.” The pitch was a nasty thing, curving like a Six Flags ride before diving over the outside corner. A-Rod’s knees buckled, says shortstop Elvis Andrus, who does a spasmodic dance to demonstrate.

Out in center field, Josh Hamilton had been tearing up nearly every inning, thinking about how merciful God had been to him. When strike three crossed the plate, he whispered, “Thank you, Lord.”

“It was good,” proclaims Oddibe McDowell.

Watching from the bull pen, C. J. Wilson was typically thoughtful: “People ask about the playoffs like it’s some ethereal experience. Like, man, there are fairies flying through the air and pink clouds of happy dust everywhere. It’s not like that. It’s just baseball.” But Wilson ran for the dog pile just as fast as anyone.

The dog pile is an art form that barely existed in the Rangers’ institutional memory. Here are the basics: Everyone wants to be in on it, but no one wants to be at the bottom of it. If you look at the pictures, you’ll see at least a dozen Rangers jumping around in a wide halo of self-preservation. Some weren’t so lucky. At spring training, David Murphy pulled up his bangs and showed me the scar where he’d gotten spiked in the head.

I have it on good authority that around this time, Nolan Ryan choked up and maybe even cried. But when I ask him about it, he avoids the question.

Me, the lapsed Rangers fan? I called my buddy Daniel and said a bunch of profound things. I sat in the silence of my Brooklyn living room for a while. And then I started looking up plane tickets to Arlington, fifteen-year hiatus from fandom be damned.

A few days after the Rangers made the World Series, Washington called his old friend in New Orleans Ron Maestri, a former college coach. This was the greatest baseball thing Washington had ever done. Yet he had already sent the World Series whirling around in his head, put it next to escaping poverty and missing out on major league stardom and getting humiliated in front of the league. He was deliriously happy, yes. But you know Wash, in his brilliant way, was gonna take about a million miles off this fastball. “Hey, Maes,” he told his friend. “We’re there.”

- More About:

- Sports

- Longreads

- Nolan Ryan

- Arlington