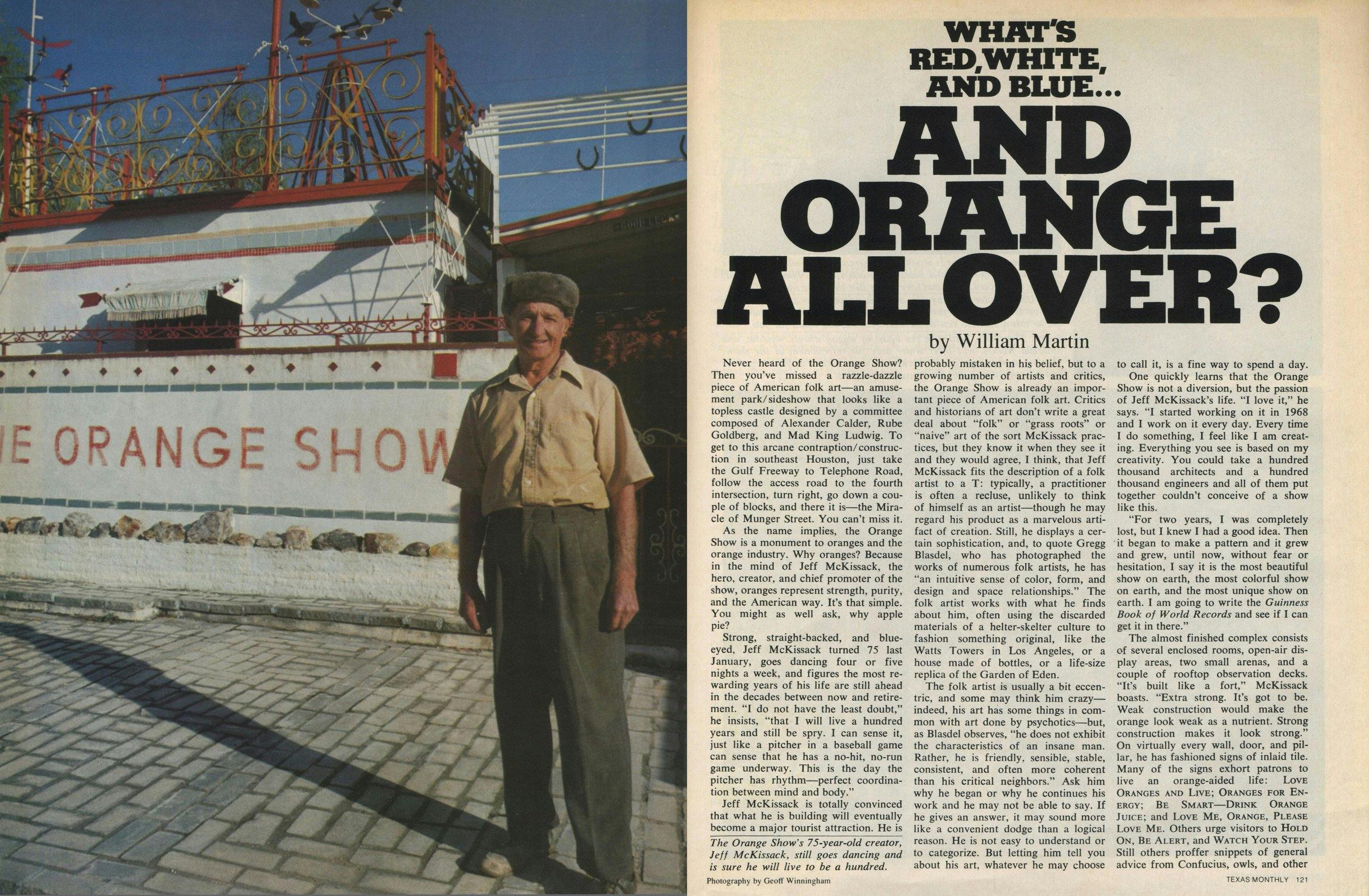

Never heard of the Orange Show? Then you’ve missed a razzle-dazzle piece of American folk art—an amusement park/sideshow that looks like a topless castle designed by a committee composed of Alexander Calder, Rube Goldberg, and Mad King Ludwig. To get to this arcane contraption/construction in southeast Houston, just take the Gulf Freeway to Telephone Road, follow the access road to the fourth intersection, turn right, go down a couple of blocks, and there it is—the Miracle of Munger Street. You can’t miss it.

As the name implies, the Orange Show is a monument to oranges and the orange industry. Why oranges? Because in the mind of Jeff McKissack, the hero, creator, and chief promoter of the show, oranges represent strength, purity, and the American way. It’s that simple. You might as well ask, why apple pie?

Strong, straight-backed, and blue-eyed, Jeff McKissack turned 75 last January, goes dancing four or five nights a week, and figures the most rewarding years of his life are still ahead in the decades between now and retirement. “I do not have the least doubt,” he insists, “that I will live a hundred years and still be spry. I can sense it, just like a pitcher in a baseball game can sense that he has a no-hit, no-run game underway. This is the day the pitcher has rhythm—perfect coordination between mind and body.”

Jeff McKissack is totally convinced that what he is building will eventually become a major tourist attraction. He is probably mistaken in his belief, but to a growing number of artists and critics, the Orange Show is already an important piece of American folk art. Critics and historians of art don’t write a great deal about “folk” or “grass roots” or “naive” art of the sort McKissack practices, but they know it when they see it and they would agree, I think, that Jeff McKissack fits the description of a folk artist to a T: typically, a practitioner is often a recluse, unlikely to think of himself as an artist—though he may regard his product as a marvelous artifact of creation. Still, he displays a certain sophistication, and, to quote Gregg Blasdel, who has photographed the works of numerous folk artists, he has “an intuitive sense of color, form, and design and space relationships.” The folk artist works with what he finds about him, often using the discarded materials of a helter-skelter culture to fashion something original, like the Watts Towers in Los Angeles, or a house made of bottles, or a life-size replica of the Garden of Eden.

The folk artist is usually a bit eccentric, and some may think him crazy—indeed, his art has some things in common with art done by psychotics—but, as Blasdel observes, “he does not exhibit the characteristics of an insane man. Rather, he is friendly, sensible, stable, consistent, and often more coherent than his critical neighbors.” Ask him why he began or why he continues his work and he may not be able to say. If he gives an answer, it may sound more like a convenient dodge than a logical reason. He is not easy to understand or to categorize. But letting him tell you about his art, whatever he may choose to call it, is a fine way to spend a day.

One quickly learns that the Orange Show is not a diversion, but the passion of Jeff McKissack’s life. “I love it,” he says. “I started working on it in 1968 and I work on it every day. Every time I do something, I feel like I am creating. Everything you see is based on my creativity. You could take a hundred thousand architects and a hundred thousand engineers and all of them put together couldn’t conceive of a show like this.

“For two years, I was completely lost, but I knew I had a good idea. Then it began to make a pattern and it grew and grew, until now, without fear or hesitation, I say it is the most beautiful show on earth, the most colorful show on earth, and the most unique show on earth. I am going to write the Guinness Book of World Records and see if I can get it in there.”

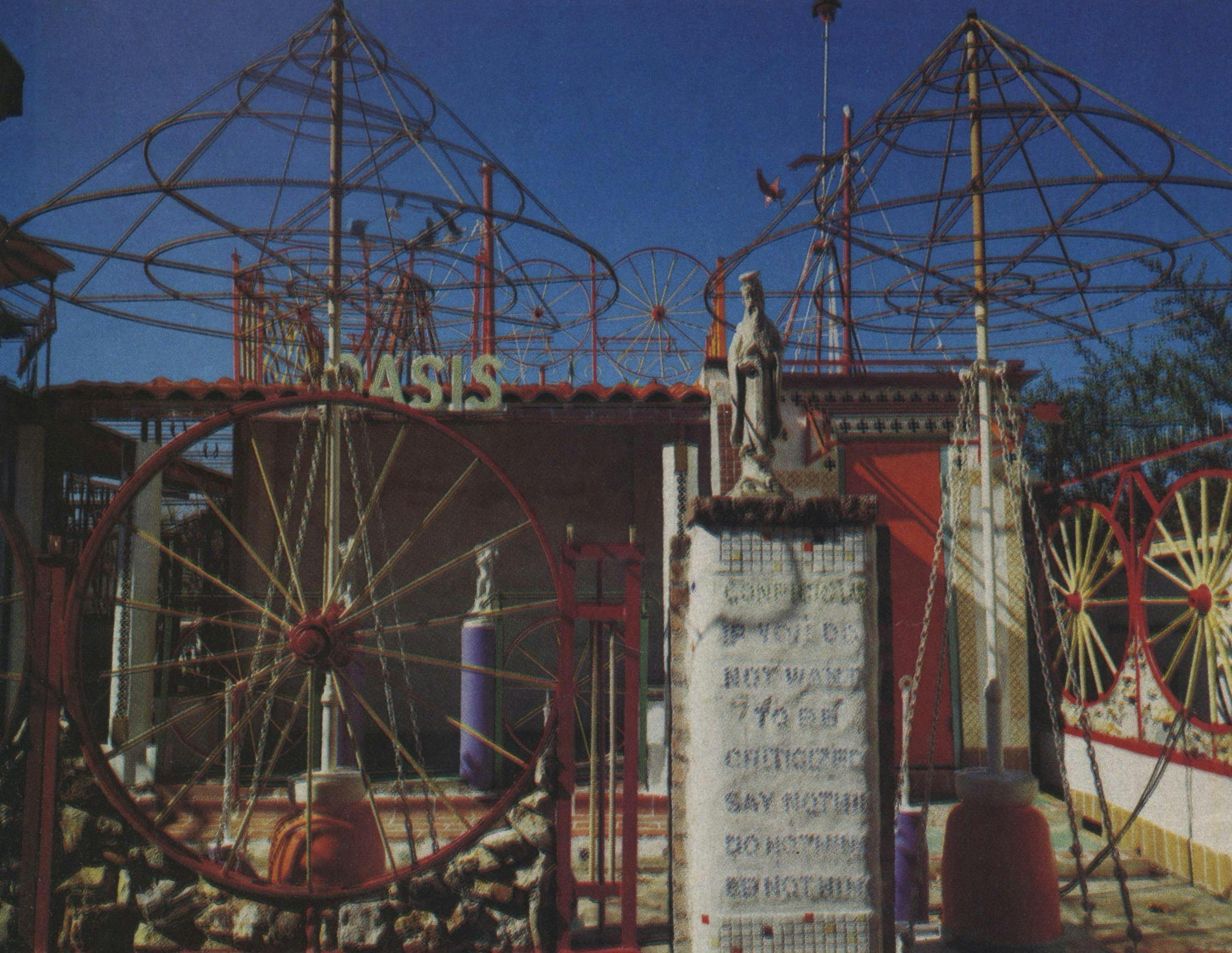

The almost finished complex consists of several enclosed rooms, open-air display areas, two small arenas, and a couple of rooftop observation decks. “It’s built like a fort,” McKissack boasts. “Extra strong. It’s got to be. Weak construction would make the orange look weak as a nutrient. Strong construction makes it look strong.” On virtually every wall, door, and pillar, he has fashioned signs of inlaid tile. Many of the signs exhort patrons to live an orange-aided life: Love Oranges and Live; Oranges for Energy; Be Smart—Drink Orange Juice; and Love Me, Orange, Please Love Me. Others urge visitors to Hold On, Be Alert, and Watch Your Step. Still others proffer snippets of general advice from Confucius, owls, and other sources of wisdom, many with a definite laissez-faire cast. Pausing before what appears to be his favorite—Whose House Is Glass Must Not Throw Stones at Another—McKissack observes, “If people would pay attention to that, they could save themselves a lot of trouble and thousands of dollars. If you start throwing stones at your neighbors, they’re going to start throwing back at you. George Herbert said that. He didn’t live but about thirty-five or forty years, but it holds good today.”

As he guides me around, McKissack fills in blank areas and empty corners with descriptions of what will eventually stand where—a monument to the American orange growers, a gift shop, a model chemical plant, a statue that once took a first prize in New York. As he talks it becomes clear that he is a man on whom the joys of process are not lost. For almost every item in the show he can—and will—provide the relevant historical, architectural, and economic data, and points with special pride to pieces scavenged from buildings wrecked in downtown Houston during the years he worked for the Post Office: roof tiles from the old Capitol Theater, a railing from a Stowers Furniture Company fire escape, and a miniature San Jacinto-like obelisk that once graced the Texas State Hotel. Many of the items, and even a collection of rocks, McKissack has picked up at antique and junk shops between here and Hot Springs, Arkansas, where he has vacationed since 1918. Everything, he assures me, would cost a fortune if I tried to buy it new today.

Obelisks, owls, and prize-winning statues notwithstanding, his greatest salvaging successes have been cast-iron tractor seats and dozens of buggy wheels. Brightly painted, they festoon every gate, fence, and partition, giving the structure the look of a playground where a giant child has dumped a box of oversized Froot Loops.

One of the two enclosed arenas contains a tiny stage and will serve as a sideshow for musical acts. A larger arena contains a crude iron vessel named the Tri-states Showboat. “We’ll put on a show with this steamboat,” McKissack explains. I’ll have miniature bales of cotton for cargo and a colored man sitting on the bales of cotton—dolls, you understand—and they will fire the cannon at the Indians. I’ve got a monkey that runs by battery and he’ll clap his hands. I’ve also got some frogs that run by batteries. We’ll stop the boat and let folks watch the frogs perform. They’re not real, but people will think they’re real. They won’t be able to tell the difference.”

Visitors who are still curious about steam-powered vehicles after the showboat extravaganza can move over to the steam buggy display. The buggy won’t go anywhere, but it will demonstrate the fundamental principles of the steam engine. I couldn’t help noticing that the show seemed to glorify steam almost as much as oranges.

“That’s right,” McKissack agrees. “I associate steam with oranges because both of them produce energy. People are interested in steam. It don’t pollute the air and it’s good for economy reasons. They’re going to have steam automobiles eventually. But nobody’ll get mixed up about the show once I get my decorations up. I’ve got orange banners and orange umbrellas with flags on them and lots of orange trees with oranges on them. They’re artificial trees made in Korea and they’re tough, too. They got wires in them. You can’t hardly tear them up. I bought a suit of clothes the other day that was made in Korea. Got it almost for nothing.”

A set of metal and concrete stairs leads to a rooftop observation deck furnished with benches, tractor seats, chairs, and, eventually, orange and white umbrellas. I’m not sure the scenery—on one side the declining asbestos-sided houses of Munger Street and on the other the Alamo motor freight company—will hold folks’ interest for long, but perhaps I have underestimated the sense of wonder present in the general population. In fairness, though, the deck does give visitors a fine opportunity to study two anemometer-like windmills that simulate planetary movement, as well as a collection of Calder-like stylized birds that perch at various points along the roof. “I got those birds out of a scrap pile,” McKissack says. “I had been cutting metal and I looked down and saw a piece of scrap cut out just like the shape of a wing. I never would have thought to design wings like that, but when I saw them I knew what I wanted.”

At the core of the complex is the exhibit room, a structure about eight feet wide and twenty feet long—keep these dimensions in mind. McKissack showed me through, explaining how the exhibits would look when completed and providing the background information I had come to expect. Two naked department-store mannequins would be part of a woodsman exhibit. The woodsman, who was a golfer in his previous incarnation, holds an ax and will be restrained by a female companion beseeching him to “spare that orange tree.” Next to the woodsman, under another spreading orange tree, the village smithy stands, and next to that a scarecrow made of pipe and metal scrap offers a homily about the needless fears of life.

Moving right along, one enters an Indian village, composed of a life-size wooden Indian, a tepee, and, still to come, a “go-rilla.” The sign behind the mélange tells a fascinating, if puzzling, story:

Indian Hate Gorilla Gorilla

Steal Indian’s Corn

Indian Hate Snake

Snake Bite Indian

Indian Hate White Man

White Man Steal All Indian’s Ideas

Take All Indian’s Land

White Man Shoot Indian

Indian Love Oranges

Orange Make Heap Big Indian Strong

“Ain’t that something?” McKissack asks. And indeed it is.

Crowded as the room is already, McKissack promises it will hold at least two other exhibits before it is finished. “I’ve got two clowns made out of round plywood and air-foam stuff, red noses and everything. They’re beautiful. They’ll go here in front of this sign: Clown Found Happiness by Drinking Cold Fresh Orange Juice Every Day. Another sign proclaimed: Purity—the Orange Is Absolutely Pure. It Grows Right Out of the Bloom Protected by the Rind. “I’m going to have another mannequin standing by that sign. She’ll be dressed up as a bride, representing purity.”

If any of the displays don’t fill the bill, McKissack claims to have at least $10,000 worth of additional exhibits stored away. “My living room is full of stuff,” he says. “You can’t wait till the last minute on this kind of thing.”

Of the various members of Houston’s art circles who have discovered the Orange Show, none is more enthusiastic than James Harithas, director of the Contemporary Arts Museum. Harithas first visited the show in 1975, at the suggestion of someone “not in the art world,” and was immediately fascinated. Until the Bicentennial flood that destroyed the museum in June 1976 diverted his energies, he frequently visited McKissack and even helped with a few odd jobs, though without revealing his museum ties.

“There is no question in my mind,” Harithas insists, “that this piece is going to be very famous before it is all over. When people visit Houston, I take them to see the Rothko Chapel, the De Menil collection, and the Orange Shrine—that’s what I call it, the Orange Shrine. It is becoming popular and well-known elsewhere. A lot of New York artists have seen it and have come to appreciate it.

“I showed it to Willem de Kooning, who is probably the most famous living painter in the world right now, and about the same age as McKissack. Obviously, they didn’t know about each other—de Kooning is a celebrated figure and Jeff McKissack is an unknown—but de Kooning immediately saw the vision and just embraced him. They got along like two old friends. You would think they had known each other for years. Later de Kooning said, ‘My God, I wish I was in that shape.’ I also took Count Panza, one of the great collectors of Europe, and it was the same thing, he was ecstatic. ‘Oh! How happy I am to have come to Houston for this wonderful experience!’ ”

What does McKissack say to these people? Harithas laughed. “He tells them about how he got something for fifty-five dollars between here and Hot Springs, Arkansas, and they love it. They are used to hearing artists say their work has this meaning and that meaning, and here they find McKissack talking about his day-to-day problems. He treats them like everybody else and they obviously appreciate it.”

Harithas doubts the Orange Show will bring McKissack any substantial income unless he sells it as a work of art to a collector who would maintain it. “I’ll bet he could get a few hundred thousand dollars out of it. That would be enough for him to sit back and fool around with it and perfect it.” If that doesn’t come about, Harithas feels the city should take it over as a monument. “It is a precious thing for the community. I intend to put the museum behind it to support it. Museums have a duty to protect works like this.”

Jeff McKissack might sell, but then again he might not, with the main chance just down the road. “I figure ninety per cent of the people in the United States will want to see it,” he says. “Of course, they won’t all be able to come. If I get a hundred thousand to three hundred thousand people a year, I’d be satisfied.” What would he do with the money? “The first thing I would do is build me a new house. I’ve lived in junk houses all my life, but when I get to be an old man I want a good place to stay. I want a house that if the president of the United States come down here, he could go in and use the toilet.” How do his neighbors feel about the prospect of living adjacent to the Orange Show and having people observe them from its rooftop? “I guess two or three of them don’t want it because it might inconvenience them, but if they are just now getting inconvenienced they are damned lucky. I have been inconvenienced all my life.”

And unfortunately the inconvenience is continuing. Just before my last visit some neighborhood boys had broken in, poured paint all over the room, and tore up some of the exhibits. McKissack had spent two days cleaning up the floor, but the mannequins were still paint-splattered and a sad-looking deer was missing its antlers and an eye. But the moving spirit of the Orange Show, happily, had not been broken.

“It was three kids from down the street,” he said matter of factly. “I bawled them out, but I didn’t say nothing to the parents. Ain’t no use to worry them; I wouldn’t get it back and the kids are worried to death already. See this churn? I bought it up in Hot Springs, Arkansas, for thirty-five dollars. I got a frog that is going to sit on a stool right beside it. It’s going to be a happy frog, don’t you see? It’s for the kids, the children. You gotta have something for everybody.”

As he spoke, I read the sign that will hang behind the world’s first frog and churn display:

TWO EAGER-TO-LEARN FROGS FELL INTO A CHURN.

One frog croaked, “I can’t make it.

I can’t make it.”

The frog quit kicking and drowned.

The other frog croaked, “I can

make it. I CAN MAKE IT.”

He kicked. The frog kicked. He

KICKED AND KICKED.

Finally, a cake of butter formed.

The frog climbed on top and

SAVED HIS LIFE.

Moral: Never give up.

Keep ’a kicking. Keep ’a kicking.

I suspect Jeff McKissack made up that story. If he didn’t, it is clear he got the point.

- More About:

- Texas History

- Longreads

- Architecture

- Houston