This story is from Texas Monthly’s archives. We have left the text as it was originally published to maintain a clear historical record. Read more here about our archive digitization project.

One romantic called it the radical chic party of the eighties. In attendance were a phalanx of Brown Berets, a bunch of hippie hangers-on, several single mothers over thirty, one member of the Revolutionary Communist party, and some one hundred other guests, mostly civil servants and lawyers. The majority of these thirtyish, middle-class people had been protesters during their college years, but those days of genuine radical chic were long past. They had come on this night to pay belated respects to a hero of a bygone era.

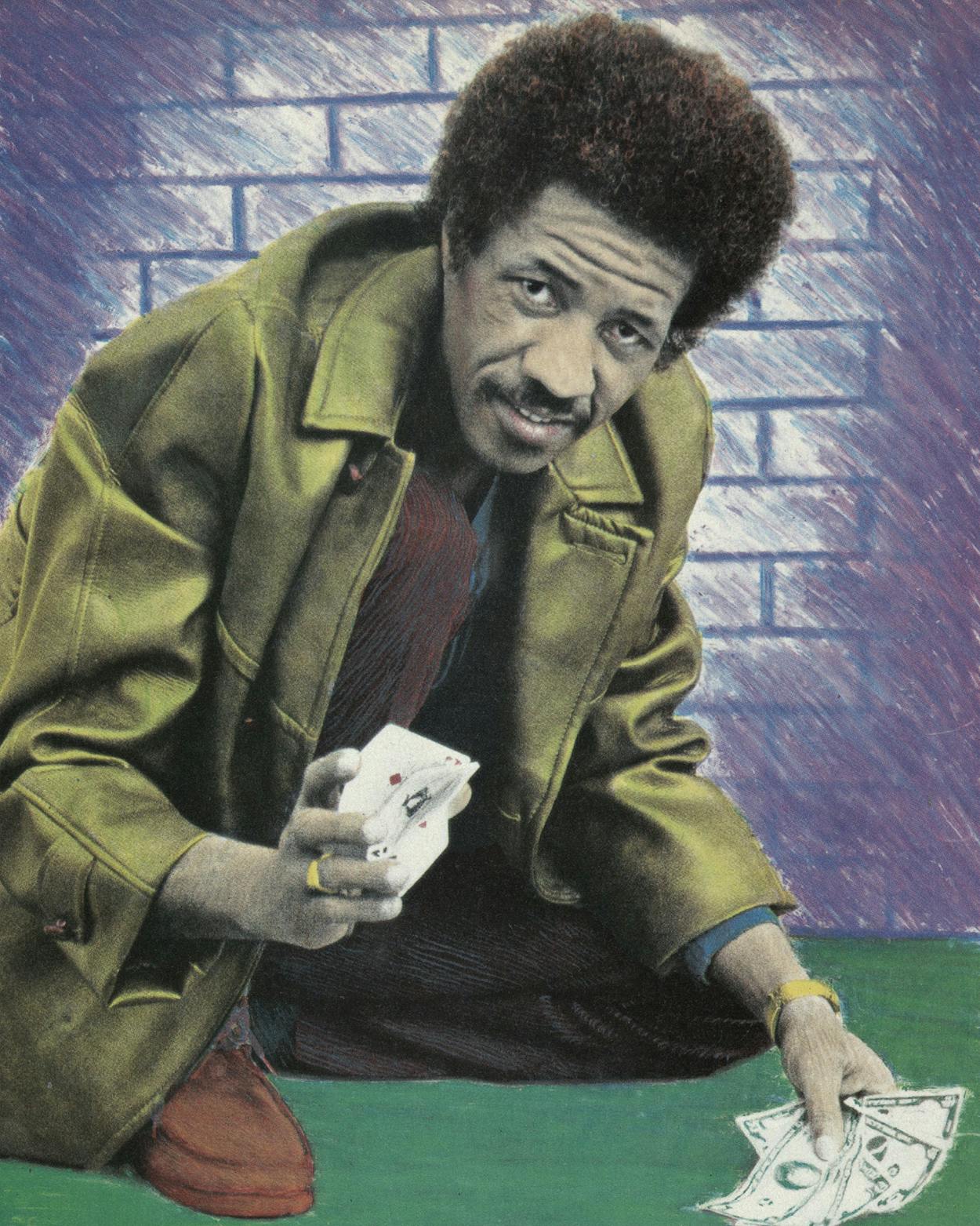

The guest of honor, Lee Otis Johnson, had once been the swaggeringest Black Power advocate in Texas. Now, however, he had turned forty and looked gaunt and haggard. His once-shimmering Afro was mottled with gray. At both the beginning of the seventies, when the fete would have been more appropriate, and at their end, Lee Otis had been behind bars.

As one of the leaders of the Student Non-Violent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) at Houston’s predominantly black Texas Southern University, Johnson had led the 1967 TSU student strike and been widely regarded as the instigator of a disturbance that came to be known as the TSU riot, in which a cop was killed and nearly five hundred students were arrested. He was most notorious, however, as the man who had been sentenced to a prison term of thirty years for giving one joint of marijuana to a police agent.

I had followed Lee Otis’s exploits for well over a decade—first as an eager participant, then as an increasingly alienated observer. During the sixties I had been one of the most active protesters in Texas and one of the first white radicals to associate with Johnson. Like him, I was passionately dedicated to the belief that we could build a world of justice and racial equality. But over the years our paths had diverged, his leading to prison and mine to the most feared strongholds of political activism and then to disillusionment.

In examining the wreckage of the movement that Lee Otis and I had helped to build, I had reached some uncomfortable conclusions. And the rumors I had heard about him since our last meeting—including persistent whispers that his last conviction, for burglary, had been a just one—only fueled my doubts. So it was with some misgiving that I faced him the night of his party. On the one hand, I wanted to know him again, to discover what the years had taught him or done to him. But even though I had put up the bond money that freed him and had invited him into my home, I was half afraid of what I would find.

Comrades in Arms

I first met Lee Otis in March 1967, a few weeks before the TSU strike began. I was introduced to him at a rally on the University of Texas campus in Austin, where I was a leader in Students for a Democratic Society (SDS). He and Franklin Alexander, another black organizer at TSU, stayed at my house for several days.

We were all deeply committed, we said, to the struggle against American racism. Our most casual attitudes exhibited a discontent with what we thought our country was in 1967: a nation gone mad in Viet Nam, with ghetto fires laying waste to its homeland. On the positive side, we were united by a vague, desperate yearning for utopia, a sentiment as ancient as the species.

Lee Otis had more than ideas and yearnings, though. He had charisma, he had grace, he had spunk. At TSU he had already made a name for himself. Once he and a buddy stood on campus with buckets of water and laundry detergent—for washing hair—and signs that read WE ARE BOYCOTTING WOMEN WHO DON’T WEAR NATURALS. The hell of it was, Lee Otis had enough charm to make the stunt work. He became a campus celebrity overnight. The incident was typical of his genius for leaving a personal imprint on his political pronouncements. Whatever his speeches lacked in profundity, they more than made up for in vivid imagery, as when he told one rally audience that the Viet Nam War was like burning a house down to kill the rats and roaches.

With his tall, golden-skinned good looks and his fondness for colorful African clothing, Lee Otis made a perfect focal point in those days of “black is beautiful.” To his middle-class white supporters he was like a piece of the True Cross. By venerating Lee Otis, whites could cleanse themselves of nagging class and racial guilt. Invoking his name was a more sophisticated, more potent way of saying, “Some of my best friends are black.”

Not one to waste his natural advantages, Lee Otis spared no opportunity to flatter and cajole his audiences. He never made a speech without an explicit compliment to the women, and they returned his admiration. If men like Martin Luther King and Malcolm X were the prophets of the civil rights movement, Lee Otis was its cheerleader.

He was no lightweight, though, as I learned one day in the Chuck Wagon, a radical hangout on the UT campus. Half a dozen of us had gone there to chat, and Franklin and Lee Otis decided the occasion called for tabletop speeches. When Franklin’s oratory was interrupted by jukebox music, we Chuck Wagon radicals looked around at each other, not knowing what to do. But Lee Otis just got up and pulled the plug. Then he stood next to the muted machine, staring down any students who had thoughts of reconnecting it.

His aggressiveness won my respect because, like most other civil rights veterans, I had scores to settle. In the South I had seen activists back down and get beaten down a hundred times. It was gratifying to see the other side intimidated, even in a minor confrontation.

Striking Out

The TSU strike had begun by the time I next saw Lee Otis. We met in a room Franklin had rented at a YMCA a few blocks from the TSU campus. There Lee Otis and Franklin were talking with the strike’s third leader, the Reverend F. D. Kirkpatrick, whom I knew from the Southern civil rights movement.

We left the YMCA for a walk through the campus. As soon as we opened the front doors, the clicking of camera shutters began. Across the street, a crowd of photographers dogged us—cops, from a half-dozen agencies. I had been around the radical movement long enough to have seen surveillance, but never—not even at the Southern Christian Leadership Conference headquarters in Atlanta—had I seen anything comparable to the corps of cameramen who sniffed our trail in Houston.

There were several issues behind the strike. The students had called for recognition of SNCC as a campus organization, for the rehiring of its faculty adviser, and for the reinstatement of Lee Otis, who had been suspended for speechmaking. They had also demanded the closing of Wheeler Avenue, a thoroughfare that cut through the campus. Over the years several pedestrians had been run over crossing Wheeler, and students viewed it as tangible evidence of the administration’s and the city’s neglect. It, like the other issues, was an expression of the students’ pervasive discontent with blatant racial discrimination.

A few days after my visit to TSU, Lee Otis and a handful of cronies came to seek support at UT. Again, they stayed with me. One evening I walked into my study and found Lee Otis working at my typewriter.

“Where did you learn that?” I asked him, since in those days few black men in their twenties, even among college students, knew how to type.

“Where do you think?” he replied. I knew only two possible explanations: either Lee Otis had been in the Army or he had been in prison. I was right; Lee Otis had a criminal record.

He told me that day not only about his prison terms but about his whole life. His father, a sawmill worker from Louisiana, had moved to Houston and worked two jobs to keep the family going when Lee Otis was a boy. Lee Otis was a brilliant student but easily bored. He preferred to play hooky and learn the skills of the streets. By the age of 12 he was expert at conning prosperous folk out of money and at picking the locks on newspaper racks. At 14 he was sent to the Gatesville reform school. At 16 he was picked up in a stolen car in Louisiana and sentenced to spend the balance of his minority in the federal reformatory system—where he learned to type. At 22 he served a year in the Harris County jail and at 24 was sent to prison at Huntsville, this time for auto theft.

At 26, in the fall of 1966, he enrolled at TSU, discovered the movement, and helped found the SNCC chapter. What he brought to the embattled campus was a hardened outlook that the student protesters sorely needed. Unlike those who feared for their future careers and ducked the notoriety of leadership, Lee Otis was an old hand at dealing with the police. They did not frighten him.

Lee Otis had talked about his criminal record almost boastfully, in much the same way that I told him about my adventures and arrests in Jim Crow Alabama. Without my asking, he vowed that his criminal affairs were all in the past, and I believed him because I needed to. Already, along with another SDS member, Alice Embree, I had arranged with Lee Otis to bring national SNCC chairman Stokely Carmichael to the UT campus.

Carmichael was set to speak on the evening of April 14, a Friday. A crowd of about a thousand students stood around the open-air stage, waiting for his appearance. Stokely was late arriving, and in the meantime I introduced Lee Otis, who harangued the crowd with excuses for Stokely’s tardiness. “Black folk have been waiting four hundred years for freedom in America,” he reminded them, “so certainly you white folk can wait another half-hour to hear about it.”

When Stokely finally showed up, two hours late, he spoke perfunctorily and then left the stage. Alice and I called for donations and the crowd responded. Nobody ever knew how much money was raised, though, because Stokely decided the split: “I’ll take the bills, you take the change.” Then he left town.

The Riot

On the afternoon of May 16, 1967, more than thirty protesters were arrested at Texas Southern and some were beaten. Lee Otis Johnson was one of those jailed. His supporters met on campus to raise bond money. Policemen appeared. A spontaneous demonstration broke out, and several protesters hurled sections of watermelon rind at the police. One, Houston SNCC figure Douglas Wayne Waller, a Viet Nam veteran, was hauled off to jail. The students dispersed, took barrels of pitch from a construction project, and set them on fire in the middle of Wheeler Avenue. Bricks were thrown from dormitories along Wheeler and shooting broke out. Police chief Herman Short ordered his cops to rush the dorms. They did, with guns blazing.

They axed their way through doors and herded residents outside. More than two dozen students were later treated for injuries inflicted by policemen. The cops left students’ rooms in ruins. They smashed television sets, radios, even a sewing machine belonging to a dorm mother. When the violence subsided, Louis Kuba, a police officer, lay dying of gunshot wounds. Some 480 students had been arrested and put in jail. Five were charged with Kuba’s death.

In November Lee Otis and Wayne Waller spoke at UT in defense of the TSU Five. “Black people are going to fight,” Lee Otis said. “All of us have taken a death vow and we will either win or die. We aren’t going to get out in the streets. When the sun goes down, a black cat with a switchblade knife can do a lot of damage.”

His animosity could hardly have been tempered a few days later when he, my wife, and I came across a float being readied by one of the all-white UT fraternities for the annual Thanksgiving parade. The float depicted a Mississippi riverboat, complete with a banjo-toting pickaninny on its rear deck. Outraged by the racist implications of the display, the three of us stole the pickaninny. Later, when the frat boys threatened to prosecute me for theft, I arranged to have the pickaninny returned to them by a contingent of about twenty black students. When the delegation arrived, one lone frat representative scurried out to retrieve the treasured object.

Busted

I next recall seeing Lee Otis early in 1968. He had come to Austin, probably on TSU Five business, and showed up at my house to ask for a ride back to Houston. He said he had to go in secret. There was a warrant out for him in Houston, he said, so he wanted to go by night, in my Volkswagen bus.

There was another man with him, who, I was told, was also from SNCC. Lee Otis called him Fastblack. He was a slender, jet-black young man, clad in a white T-shirt and jeans. A chrome watch gleamed on his wrist. Lee Otis bragged to me that Fastblack had gotten his nickname by taking that watch from a cop’s wrist during a demonstration. Fastblack, Lee Otis said, was a pickpocket.

The three of us arrived in Houston about midnight. Fastblack and I waited for a long time while Lee Otis went into his go-go dancer girlfriend’s house on unspecified business. When he returned we drove to a housing project, where Fastblack got out. Then we drove to a beer joint where we picked up Wayne Waller. It had been raining and the ground was muddy. As Wayne stepped up to my van, something fell out of his hand into the mud.

It was a derringer. He retrieved it and began beating it on the dashboard, trying to get the mud out of its barrel.

He was drunk. “Lee Otis, tomorrow is my birthday,” he whined, “and the rent man is coming. I haven’t got money to pay him.” He was nearly blubbering. “Lee, I’m going to kill him,” he blurted. I stiffened in my seat. Lee Otis didn’t even blink.

“If you’re going to kill him,” Lee Otis said, “do it this way. Go to the SNCC office and get that rifle. You know, the one that’s against the wall. Then—you know how the freeway passes by the house? Well, go get under that freeway ramp, lay there, and when the rent man goes up to the house, then you take care of him where nobody can see.”

Wayne nodded drunkenly. Lee Otis explained again and Wayne nodded again. Yes, he understood. Wayne got out, and Lee Otis and I left.

Waller did not kill the rent man, as far as I ever knew. He was drunk when we spoke to him. But the exchange in my car worried me, because it showed that Lee Otis didn’t care what Wayne did or what happened to the rent collector.

A few weeks later, on April 14, 1968, at a memorial service for Dr. Martin Luther King, Lee Otis verbally assailed one of the speakers, Houston mayor Louie Welch. Three days later he was arrested for having passed a joint of marijuana to a man almost everyone knew was a police cadet. The arrest was ironic. Lee Otis was not, in those days, a habitual user of any drug. Rumor inside the Houston Police Department still has it that he was set up. But in August 1968 an all-white jury convicted him and sentenced him to thirty years in prison.

Hard Times

Today, 1968 is remembered as the prime year of protest because it was the year of the Democratic Convention demonstrations in Chicago. But the movement’s death throes began that year, too. The civil rights crusade withered after the assassination of Dr. King. SNCC wrapped itself in the shroud of Black Power and lost its influence. SDS was ripped apart by hippies and Maoists. By mid-1969, most radical organizations were, for practical purposes, defunct.

I enrolled in law school that year but flunked out almost immediately. I was divorced soon thereafter and joined the Army as an antiwar agitator. The Army promptly kicked me out. I fled to New Orleans, where other shell-shocked Southern radicals were regrouping. We founded a publication called Midnight Special and tried to find our footing in the seventies. But before we had a fix on the decade, most of us were waylaid by alcoholism or drugs.

My West Texas dry-county upbringing saved me from personal degeneration but still did not give me an explanation for the way the world was. In 1972, during the campaign to free Angela Davis, I joined the Communist party. 1 did it because the party was thoroughly integrated and had been geared to fighting racism for fifty years. It was also a move to pay my respects to those who had gone before me and had seen the folly of the New Left’s cocky, self-defeating ways.

In the thirties joining the party had been a stylish thing to do, especially in intellectual circles. But the Hitler-Stalin pact and McCarthyism had changed all that. The party, always viewed as sinister on the West Texas horizons I had fled from, was also isolated and unwelcome to the New Left. But in 1972, when the protest movement was going under, joining the Communists was for me an affirmation of a desperate desire for social justice. I was like a man who, during a divorce, gets the word “Mother” tattooed on his biceps. He tells himself that women, like movements, may come and go, but Mother will always be there. One’s mother may be ugly or less than virtuous; some mothers are, even in the eyes of their sons. But still, she is an immovable fixture in a transient world. Every radical has been admonished that he is on the path to communism. When I joined, I felt as if I had tattooed a message for the FBI—or anyone else who might be watching: You were right. Watch out for this man.

But most of all, I suppose, I joined because Sergent Caulfield wanted me to. Sergent was a retired sharecropper and brick mason from Baton Rouge and the senior member of the Communist party in Louisiana. He didn’t much care for white folks, but he took to me and he helped me by challenging many of my most ingrained beliefs. Once, for example, I asked him, “Are the cops bad around here?”

“The trouble,” he replied, “is that we can’t get enough of them on this side of town. All they want to do is protect the rich people’s houses.” It was the first time I had ever heard a radical endorse law and order. Seeing the world through his eyes, I came to believe that criminals—no matter what their race or their politics—were only parasites on the working people.

Free at Last

With the attrition of my regiment of radicals, a new wave of protesters came forth to defend Lee Otis Johnson. In 1970 a group of these new-style student rebels at the University of Houston shouted down Governor Preston Smith with chants of “Free Lee Otis! Free Lee Otis!” Smith told a reporter that he had misunderstood them. He had thought they were antipoverty people chanting, “Frijoles! Frijoles!”

In the end, though, it was his lawyers who freed Lee Otis. In his original trial, they had asked for a change of venue, citing the intense publicity his case had generated in Houston. Their motion was denied. In the spring of 1972, four years after he was sentenced, a federal court ruled that the denial violated his constitutional rights. Lee Otis was released from prison for retrial. The Harris County district attorney’s office decided not to retry him. Public opinion about pot had changed in the interval, and so had the law. Passing a joint had become a misdemeanor in Texas.

Lee Otis returned to Houston in triumph. The marijuana conviction had given him notoriety—and admirers—even outside Texas. Opportunities surrounded him. An old friend had written a movie script that depicted Lee Otis as a folk hero. It was the era of black films, and several well-known actors were interested the story. Galas were staged to publicize the project and Lee Otis was offered loans all over town.

But sympathizers in the Houston establishment urged Lee Otis to leave the city. The death of Officer Kuba had never been solved, the TSU Five had not been convicted, and Lee Otis would pay for it if the cops had their way, his friends warned. If he intended to stay in Houston, he’d better keep on his best behavior. After several arrests—but no convictions—Lee Otis gave up and went to California, where he found a job as a paralegal and settled down to a life of relative obscurity. His newfound peace was shattered in June 1974, however, when his younger brother, who had been an outstanding scholar and an auto industry executive, was found murdered in his Detroit apartment. Lee Otis came back to Houston for the funeral and stayed.

Five months later he was accepted as an outpatient in a state-supported drug clinic. His detractors said he had become a heroin addict who stole to survive. Lee Otis denied the rumors, but before long he was arrested and charged with five separate felonies. In April 1975 he stood trial for burglary.

The trial was complicated by a confession Lee Otis had signed and then recanted, by the inconsistent testimony of the prosecution’s key witness, and by the disappearance of a woman who Lee Otis said had been with him at the time of the alleged break-in. Lee Otis claimed that the woman had been staying in the house and that they had entered it to retrieve her property. But the jurors chose not to believe him in the absence of corroborating testimony, and under the Texas enhancement statute—which can be used to lengthen minimum sentences, at the prosecutor’s discretion—the jury was required to sentence Johnson to a prison term of at least fifteen years. It gave him seventeen years. In May 1977 the Court of Criminal Appeals voted to uphold his conviction, and soon afterward all the remaining charges against him were dropped. And that’s when Lee Otis played the ace he had had up his sleeve all along.

During his years in prison he had read extensively in the law, and throughout the burglary trial he had deluged the bench with motions and documents of every description. Two of these were petitions for removal—a process by which federal courts can intervene in state court actions before or during a trial. Such petitions are used mainly in civil rights cases. Under the law, a plea for removal required a hearing before Lee Otis’s trial could continue.

But the two petitions were different. One was clearly for removal. A federal judge ruled against Lee Otis and his trial proceeded in the state court. The second petition, however, began with a simple claim for money damages, an action that did not require immediate disposal; the plea for removal was worked into the back pages of the document. Lee Otis also presented this second petition to the clerk as if it were an afterthought to the first one, focusing the clerk’s attention on the first petition. It was an old trick he had learned in prison, an inspired adaptation of the familiar sidewalk con game called three-card monte.

The second petition went to a second federal judge, where it languished because it apparently needed no immediate action. After his conviction, Lee Otis claimed that his trial was invalid. He revealed that the second petition contained a plea for removal and argued that the state court had had no jurisdiction while the petition was pending. Lee Otis’s conviction was set aside to await the conclusion of his litigation, and he was released on a writ of habeas corpus. He regained his freedom, on a bond I posted, this January. He came to stay at my house.

Coming Home

There were problems from the first. Lee Otis had no money. He had no transportation and no job. I suggested that he catch a bus downtown to the employment office.

“A bus!” he exclaimed.

“Sure, man, why not?”

“A bus—man, you ought to know that black folks have a thing about buses.”

Lee Otis was reminding me that the civil rights movement had begun with the Montgomery bus boycott.

“Look, brother,” I told him, “you ain’t pulling that guilt trip on me. I’ve been around too long.”

Lee Otis laughed. He didn’t argue anymore—but he didn’t ride any buses either. Instead, we went to Houston, where his father gave him an aged eight-cylinder gas guzzler. When Lee Otis got the car registered in Austin—everyone who knew him insisted that he not live in Houston, where cops still remembered the TSU riot—he moved out of my house.

He wound up in a residential co-op full of old movement folk, in a room across the hall from Alice Embree, my old SDS friend. He found a job as a teacher in an educational center for troubled youths. But Lee Otis didn’t adjust. Perhaps he never had a chance. He had come out of prison with hives, for which a doctor had prescribed a drug called Atarax. It helped control his hives, but he began acting strangely. He was nervous and talked endlessly. I consulted a physician and found that hyperactivity is a rare but possible side effect of Atarax. Lee Otis said he recognized what the drug was doing to him and promised to quit taking it.

For a while he did. Then one night, at a drive-in fried chicken restaurant, he backed his gas guzzler into another car, whose driver demanded $150 in compensation. Lee Otis didn’t have the money. He had barely established himself. Gasoline expenses were draining him and his medical appointments had been expensive. Within days of the accident, his leopardlike pacing and incessant worry returned.

In mid-March Johnson’s friends began hearing rumbles from his job. Lee Otis told them that he had won a raise, to a salary of about $900 a month, but he also said that other teachers wanted him fired because they were jealous of his popularity. There were troubles at the co-op, too. A stereo had been stolen from a student who lived there, and Lee Otis, after some delay, confessed to knowing about the affair. He said a buddy had taken it.

Then one day Lee Otis came to the co-op in the company of a woman who, he said, had temporarily turned to prostitution because her house had burned down. She stayed in the co-op overnight and most of the next day. After the woman left, Alice Embree discovered that her jewelry was missing. During the same period there was a theft at the law office where the party for Lee Otis had been held. Somebody had come in, probably with a key, and made off with a dozen credit cards and a quantity of postage stamps. The firm called keys in. Lee Otis was one of the keyholders.

About two weeks later a student who lived at the co-op charged that during a household dispute Lee Otis had struck her. The new hassle was the last straw for the co-op’s resident directorship: it gave Lee Otis the boot. He came to me again. He wanted to stay a few days in my house, for he had nowhere to sleep. I said okay and gave him a house key.

Looking Back

Beyond that, however, I wanted no part of Lee Otis’s exploits—political or otherwise. In 1974, about the time he came back to Houston from California, I had married Marta Luz, an apolitical foreign national. She could not find a job, and overnight I had to stop worrying about world politics and start worrying about self-support. I quit the Communist party because I didn’t have time for it and because I knew my membership would imperil her immigration status in this country.

By that time, too, I had found out something about myself: I couldn’t stand the heat. In my ten years of political activity the FBI had compiled a 226-page dossier on me, forged a defamatory letter about me, questioned my neighbors and professors, and informed on me to an employer. In the parlance of the movement, I finally just burned out.

More important than these considerations, however, I had learned that real Communists are not like me. They are staid, disciplined, settled souls—believers, not heretics. Their nonconformity is limited to politics. I had long ago asked myself why I had become involved in the movement, and the answers had not pleased me. I had joined the civil rights struggle not only because I believed in its intellectual premises but also because black people were fighting the same shiny-suited hypocritical establishment that I myself had felt oppressed by. I joined out of resentment over the economic troubles my family had suffered during my youth. Hostility had led me to the movement, which had given an outlet to what I now saw as the monster in me.

One afternoon in April I told Lee Otis all this, then tried to get him to talk about himself. “Why do you think you got into the movement?” I asked him.

“Because of the system. You know that,” he grumbled.

“Yeah, Lee Otis,” I pressed. “But all of us were born in that system. When was it you decided that it stinks?”

“Back in Huntsville, on that auto theft thing. We were working in the fields, and I got to thinking. I saw that it wasn’t my fault I was in the joint. I was there because of what the system had done to black folk.”

“Yeah, Lee Otis, but why were you there? Why was it you? Why wasn’t it your brother, or all black folks?”

“Because they can’t have us all in prison, man!”

“Yeah, but why did they have you and not somebody else?”

“Because the rest have been brainwashed.”

“Then why haven’t we been brainwashed like them?”

“Because we can see, man. I’m not blind, people in the movement ain’t blind. Everybody else just wants to join the BankAmericard set, that’s all in the world they want.”

Lee Otis knew I had a BankAmericard. I let the subject drop. Lee Otis walked out of the room without saying so long or looking back. He went upstairs, then came back down and left the house.

A few minutes later I drove to a nearby convenience store to fill my Volkswagen with gasoline. Lee Otis was inside, paying for a purchase of some kind. A pile of pennies lay on the counter, and he was counting them out. There was something strange about that, I thought. Lee Otis hadn’t been out of prison long enough to amass a penny collection, and I felt sure that if anyone had given him so strange a gift as a pound or two of pennies, he would have mentioned it. I said hello to him and looked away, as if I hadn’t noticed the pennies. But he saw that I had. I went back home and checked the basket where my wife kept stray pennies. It had been nearly full, but it was now half empty. The discovery hurt.

Falling Out

Lee Otis did not come back to the house that night, and I didn’t see him for ten days. One Friday night, however, he telephoned. He said that he was living in a motel on the fringe of the East Austin ghetto and that someone was trying to kill him, for reasons he didn’t know.

“Aw, come on, Lee Otis, why are they after you?” I prodded him. He insisted that he didn’t know. I advised him to flee, even to Houston if necessary. He said that instead he wanted to borrow my shotgun.

“Lee Otis, I can’t do that. You’ll get yourself arrested.”

“Man, you know I ain’t got no convictions,” he lied.

I told him to come to my house and I’d give him the shotgun. Then I explained the problem to Marta. All five feet of her stood straight as steel when she told me that under no circumstances was I going to lend Lee Otis a shotgun.

“He’ll go back to prison,” she shouted.

“Yeah, but if I don’t lend it to him, he may go to the graveyard. He’s going back to prison, anyway, sooner or later,” I countered.

“You just can’t let people down that way,” she told me. “You’ve got to try to talk to him.” I decided she was right.

When Lee Otis pulled his car up in front of the house, I invited him in to talk. He was tense, drawn, and obviously frightened. I suspected he was taking Atarax again and that he had crossed somebody in some criminal pursuit. I demanded that he tell me the story, but he wouldn’t.

“Listen, the less you know, the better,” he told me.

I insisted that I wasn’t going to give a shotgun to someone in his condition, and finally he left, still very agitated.

That evening Marta and I went to a party. When we returned about midnight, Johnson’s car was parked in our carport. I parked my Volkswagen behind his car, so it could not be driven off. Then I walked up to the patio gate. It was still locked. I had never given Lee Otis a key to it. The sliding glass door at the back of the house was open, and Lee Otis came out, meeting us on the patio. His hair was quite literally standing on end. His jaws were drawn tight, his nostrils were flared, and his eyes were opened wide. I had never seen him so frightened. He began whining, in a voice that creaked and trembled. He raised a hand wrapped in a washrag.

“Man, they cut me up over there at the motel, they’re going to kill me,” he rattled.

Marta put her arms around his neck. “Take it easy, take it easy,” she soothed.

“They’re going to kill me,” he insisted. “That’s the only reason I came here.” He turned a little from Marta, facing me. “Man, I’ve just got to have your shotgun, that’s all there is to it.”

I snapped his key ring from the lock of the back door and went into the house. I went upstairs, with Marta following. Lee Otis stayed below. I told Marta to check on her jewelry. She did. A half-dozen items were missing. Marta sat down and started crying. I led her downstairs by the hand and confronted Lee Otis.

“My buddy must have took it,” Lee Otis groaned, touching his chin as if trying to remember something. Then he moved toward the back of the house. I followed. He went out to the patio and whistled.

“I let my buddy out the front door. He’s over there somewhere, somewhere out in the street or on the side,” he told me.

I walked out into the street, and there was another black man, about 25, handsome and well built. He was a stranger to me. He came to the carport, wordless and nonchalant. He sat down in Johnson’s car. Lee Otis kneeled beside the car’s open door and waved me off. I went into the house, hoping he could talk the jewelry back.

Lee Otis came back into the house a few minutes later. “The dude says the stuff is upstairs on the bed,” he told me. As we climbed the stairs he babbled, “Man, you know I didn’t know anything about this, I wouldn’t bring nobody here to rob you. Man, I don’t know this guy, he just jumped in to help me in that hassle over at the motel.”

But I wasn’t listening—the jewelry was not on the bed. I took the shotgun out of its hiding place. When he saw me with it, Lee Otis reached into his front pocket and handed me three shells. “Here, I found these in your desk,” he said.

I went outside and was surprised to find that Johnson’s buddy had not run. He was still sitting in the car. He did not start when he saw my shotgun.

“I want that jewelry, brother,” I told him. The man said he didn’t have it.

Marta had come out too and heard his answer. She headed next door, toward the house of a neighbor who is a policeman. I turned to Lee Otis. “The guy next door is a cop,” I told him.

He shrugged. “You know the cops will lay it on me,” he said. I lowered the shotgun, training it on Johnson’s friend. Then I hollered to Marta to come back.

“Now, let’s have that jewelry,” I barked, as menacingly as I could, moving forward as if to shoot. Johnson’s buddy flinched this time. “Let me talk to Lee Otis,” he said.

Marta and I went back indoors while the two men talked. After a few minutes I grew impatient and went out, still carrying the shotgun. Lee Otis told me to call Marta out. I did. Lee Otis turned his back to her for a minute, then handed her a sock filled with her jewelry. She turned to the other thug.

“What’s wrong with you? Why did you take my things?” she demanded.

“I’ve been taken so many times, I don’t know what taking is,” he told her. It sounded like something Lee Otis would say.

“Listen, it’s not the value of my things that counts. It’s what they mean. My husband gave me these things,” she cried, raising the sockful of jewelry to his eye.

“Oh, it’s not the value, huh?” he sneered. She turned away in disgust.

I ordered the thug out of the car and had him empty his pockets. Marta reviewed his holdings and came up with an additional item, a pair of earrings. I told the thief to stay outside the car, at its front fender. Then I searched the car. Nothing of mine or Marta’s turned up, but I did find two vials of street drugs and a Baggie of marijuana.

“Brother, I’m taking these from you, as a friend,” I told Lee Otis. “You’re messed up enough already.” He just nodded. I told him and his buddy to leave, but Lee Otis protested.

“Don’t send me off with him, man,” he whimpered. “I don’t know the guy—he might do something to me for ratting to you.”

I went indoors, called a taxi, and waited at the carport until it came. Then I gave the thief $5 and told him to get in the cab. As he grabbed its door handle, I told him to turn around, toward me. When he did I pointed the shotgun at him. “Now, brother, I don’t ever want to see you again,” I told him.

“Tell Lee Otis to look me up,” he taunted as he got into the cab.

Farewells

Lee Otis was inside rummaging around in the bathroom that opens onto my study. “I need to bandage my hand,” he said. I pulled a roll of adhesive tape from a drawer. “We need something to cut it with,” he told me.

I stepped into the study to get my knife. The sheath was empty; my three-inch lockblade was gone. I went back to the bathroom, to find that Lee Otis had already taped sections of the washrag around his hand.

“What did you cut the tape with?” I asked him.

“I’ve got a knife,” he said, looking away. I didn’t comment. A month ago he had shown me the no-account pocketknife he carried. I suspected that he had my knife now, but I wasn’t going to threaten him or demand a search. I pulled his key ring from my back pocket, removed the house key, and handed the rest to him. But Lee Otis wasn’t ready to go.

The headlights on his gas guzzler were smashed, all four of them. Lee Otis claimed they had been broken in the ghetto fracas earlier that night and told me he had no money to replace them. I drove him to a truck stop, where I bought low beams. We came home and installed them. Then I gave Lee Otis $5.

“Man, you’d better get away from here,” I counseled. “Go anywhere you can. You’re messed up, man, and you’re headed for trouble.” With a muttered promise to do as I said, he got into his car and drove off.

Inside the house, I conferred with Marta. She was angry—she thought I’d been conned. “You know what? Lee Otis wasn’t cut over in East Austin. He cut himself when we pulled up to the house, just to have a pretext for being here,” she snapped.

There was no proof to support her suspicion, but it was plausible. I had seen no blood on the steering wheel of Johnson’s car or anywhere else except on the floor of our upstairs bathroom. Still, I was relatively satisfied. We had gotten back all of our possessions save that knife, which was mine, and the thieves had not found the one thing I cared about most: the jewel I planned to give Marta for our sixth wedding anniversary.

“Well, at least they didn’t get your anniversary ring,” I told her.

“Don’t worry,” she replied. “There’s not going to be any anniversary.” The announcement did not entirely surprise me. We’d been having troubles lately and had been talking about divorce. Marta started explaining, but she need have said little. It was my job again. She had endured my forays into Mexican guerrilla camps, bikers’ hangouts, Boys’ Town honky-tonks. But the encounter with Lee Otis was the last straw—this time the violence had struck home.

Burning Bridges

On Monday I sacked up various possessions that Lee Otis had left around the house during his earlier stays and took them to his lawyer’s office. The next day I got a call from Denise,* an old SDS colleague and ex-party member whom I’d seen only once in the past five years, at Lee Otis’s party.

“Have you seen Lee Otis?” she wanted to know.

“Not since last Friday night,” I told her.

“Well, he ripped us off last weekend. He took six hundred dollars,” she said.

“Oh, Christ,” I said. Then I explained what had happened at my house.

“Well, why didn’t you warn us what he was up to?” she scolded.

“I don’t know. I didn’t know he would go to your house and I got back most of what he took from us, so I figured there was nothing to complain about,” I said uneasily.

“Yeah, but you knew who his friends were, and you knew that sooner or later he’d rip us off too,” she said.

Then she told me what had happened. Lee Otis had gone there, showing his cuts, asking for treatment and a place to sleep. Denise had taken him in. Her husband, an employee of a catering company, had the weekend’s receipts on hand. Denise, her husband, and her mother left the house for a few hours, and when they came back Lee Otis and the money were gone. When she discovered the theft Denise went to the East Austin motel where Johnson had told her he’d been staying. He had checked out.

I called Alice Embree and the other co-op resident who had been robbed. Those of us who hadn’t already made police reports did so now. The police told us that without more evidence they could not make a case against Johnson for any of the incidents except mine. At any rate, none of us wanted to file formal charges without first talking to Lee Otis.

Within days Alice, Denise, and I began to get phone calls from Lee Otis’s supporters—the ones he hadn’t robbed. The callers asked us in the name of the movement, mercy, and the antiracist struggle not to inform on Lee Otis. Some of the callers did not ask. They lectured.

I thought for several days and decided not to pursue matters with the police, because I realized that Lee Otis had given me exactly what I had bargained for. Before he got out of prison, I had told him that I wanted to do a story about him. He had not asked me to go his bond; I had volunteered it. I had intended to have him indebted to me.

He understood what I wanted. I wanted to know who he really was. And in his own way, I suppose, he tried to tell me. I remember one evening when I was trying, without success, to housebreak a new puppy we had. Lee Otis’s suggestion on the matter revealed far more about his perception of how the world works than it did about his knowledge of dog training.

“Never reward the dog,” he counseled me. “Always punish him, that’s the main thing.”

Never reward the dog . . . what could have been more transparent? And yet, just two weeks before the theft I told Lee Otis that I was still having trouble distinguishing between Lee Otis Johnson the advocate of revolution and Lee Otis Johnson the practitioner of rip-offs. When he took my knife he finally made it clear to me. They were the same.

I told Lee Otis’s friends that I had decided not to prosecute. The phone calls stopped. I began to worry about my own safety, however. It seemed to me that I held the keys to Johnson’s future in my hands. His liberty depended upon my continued goodwill. By this time Marta had left and I was alone in our house. I had never wanted to own a pistol, but now I bought one. I figured that Lee Otis would be worried. Sooner or later he would appear.

A week after the scene at my house, I got a call from someone at the co-op. Lee Otis had returned there to claim his possessions. I decided that I’d better warn him not to show up at my house too.

Denise had also been telephoned, and she had persuaded Lee Otis to meet her and Alice and me in a park near the co-op. I drove to the spot. He pulled up there a few minutes later, dirty and unshaven. His Afro was uncombed and he was more gaunt than ever. He was also in a state of rage. He waved his arms and pointed wildly, saying he was being framed by somebody and that I was in on the scheme.

“What about the things you took from my house?” I asked him, keeping my distance.

“What things? You know I didn’t take nothing.”

“Yeah, well, Lee Otis, you’ve sure got the wrong kind of friends,” I told him, not mentioning my knife.

“Man, I’m new to Austin, I can’t be expected to know the character of everybody in town,” he spat. That was enough for me. I left Denise and Alice to argue with him and went home.

I had half a mind to file charges. I called one Communist official to ask his advice, and he said that if he were in my shoes he would do it. To give myself peace and quiet to think things through, I decided to leave the house. I considered my options. My parents would take me in, I knew, but they had suffered enough during the years of my activism. The radicals I knew might shelter me, but they, I thought, were likely to demand endless justifications for anything I said or wrote about Lee Otis. All things considered, I decided on the anonymity of a motel.

I packed up my typewriter and checked in. For three days I sat and wrote, sat and thought. During that time, I made a dozen calls. On one of them, I learned of yet another burglary, this one at the home of Johnson’s former girlfriend and her brother, a medical technician who had once treated me when I lay hurt and helpless in an Austin hospital. That news made up my mind: society was not going to gain by leaving Lee Otis at liberty. Even though it meant that he might be returned to prison and even though I knew the act would make me a virtual traitor in the eyes of many old friends, I picked up the phone and made arrangements with the police.

*A fictitious name.

- More About:

- Politics & Policy

- TM Classics

- Longreads

- Houston