I knew William Wayne Justice was ailing—I had heard rumors, plus I hadn’t seen him at the YMCA gym for a couple of years—so I wasn’t surprised when I heard he died Tuesday, October 13, 2009, at an Austin nursing home. Justice was physically a small man, but morally he was huge. He was one of the old-time iconic judges like Douglas or Brandeis, not afraid to let politics or even precedent get in the way of something he thought was fair—like forcing schools to integrate and forcing prisons to be more humane. Few of us are unfortunate enough to get saddled with a name like his, but Justice actually lived up to it.—MH

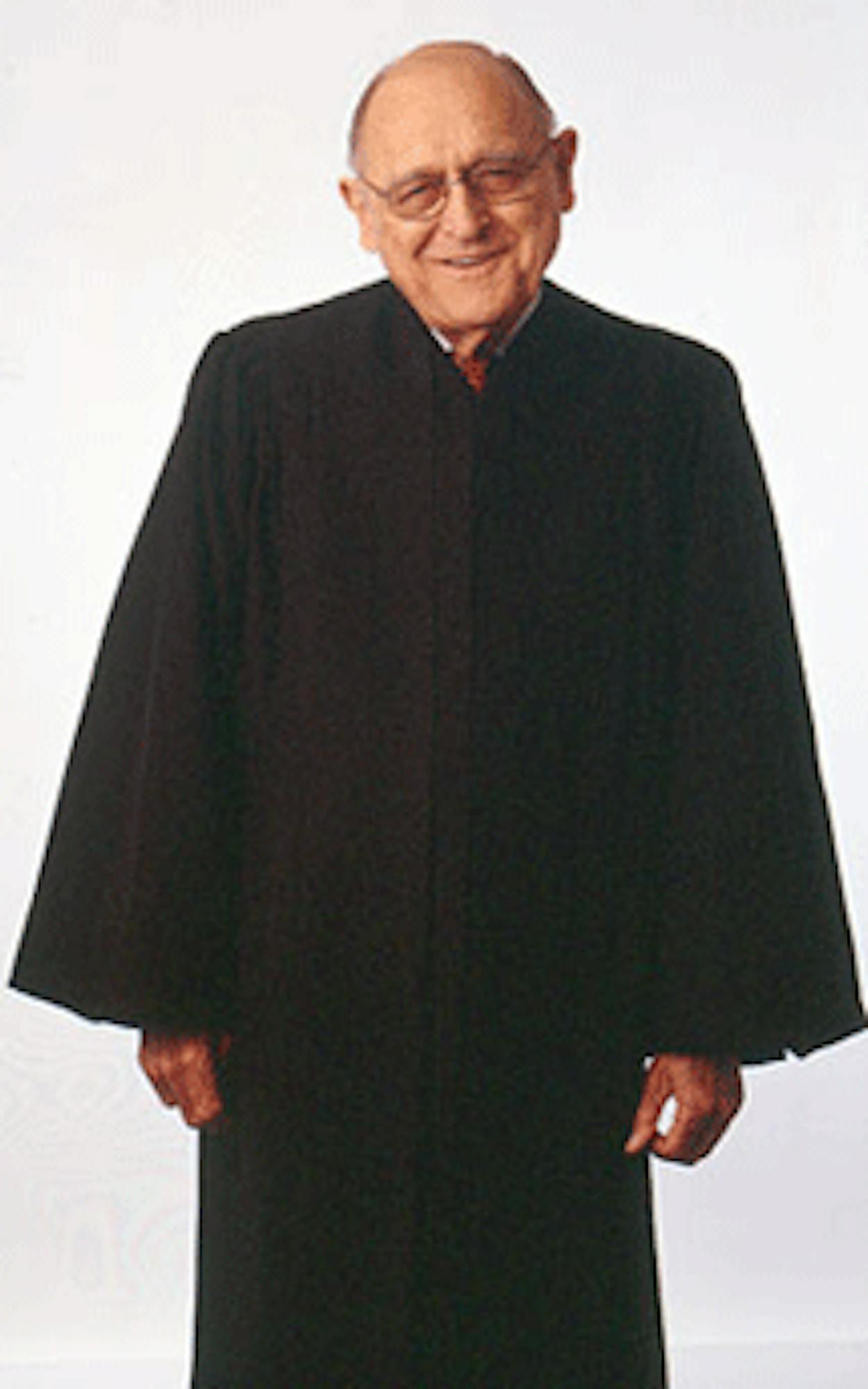

“SO,” I ASKED 86-YEAR-OLD FEDERAL judge William Wayne Justice in the weight room at Austin’s downtown YMCA, “did you consciously set out to become known as the most hated man in Texas?” The judge, who comes to the gym twice a week and was wearing black shorts and a burnt-orange Longhorns shirt, smiled and shook his worn head. “But,” I persisted, “you had to have known the reaction you would get.” He nodded and said, “I had a pretty good idea what I was getting into.”

What Justice, appointed to the bench by LBJ in 1968, was getting into was, in short, dragging the state into the modern world. The Athens-born judge did it most famously in 1971 by ordering East Texas schools that had been ignoring integration to obey the law. The good people of Tyler, where Justice was based and where he lived, were not pleased. After the decision forced local high school Robert E. Lee to jettison its Confederate band uniforms and rebel flags, the phone started ringing and the hate mail started coming. Bumper stickers were printed that read “Will Rogers never met Judge Justice.” Carpenters working on his house walked off the job when they found out who owned it, and his wife, Sue, was refused service by local beauticians. “Our social life dwindled,” the judge says in his easy drawl. “But you know, I’d taken an oath to defend and protect the Constitution, and I was going to do my best.”

Through the seventies and eighties, he would, among other things, force the state to both overhaul its prison system and offer bilingual education in its schools, acquiring a reputation among some as a champion of justice and among others as a judicial activist. After thirty years in Tyler, the Justices moved to Austin to be near their daughter, Ellen. Now the judge works out of his downtown office, surrounded by photos of his past, including autographed pictures of LBJ and Ralph Yarborough; his coffee cup says “WWJ: Populist.” When he’s not there, he’s driving to Del Rio once a month, where he has two hundred cases on the docket, or pumping iron at the Y for future battles.

Looking back at a career of siding with underdogs, he says the decision he’s most proud of is one in 1978 requiring the state to allow the children of illegal immigrants to go to public school tuition-free, just like everyone else. “How many kids have gone to school because of that decision?” he asks. (Millions, easily.) The decision was upheld by the Supreme Court in 1982; indeed, most of Justice’s decisions have been upheld by higher courts. Now he’s getting ready for a new round in his fight to enforce his 1981 bilingual education ruling, which should hit his court sometime this year. With attitudes toward immigrants being what they are these days, it’s a safe bet that Justice will be hated again—and, again, for all the right reasons.