Many will say to me in that day, Lord, Lord, have we not prophesied in thy name? and in thy name have cast out devils? and in thy name done many wonderful works? And then will I profess unto them, I never knew you: depart from me, ye that work iniquity. Matthew 7: 22-23

“Now the way I hear,” Malcolm, the preacher, went on, “people are getting sick in The Exorcist not because of the vileness in it—people are used to that nowadays—but because the devils in them are getting stirred up from hearing the name of Jesus.” I didn’t observe what my logically minded brother would later point out—that this also explains why so many people throw up in church. That wasn’t the only time I was slow with the counterpunch during two separate interviews with Malcolm, during two separate witch-hunts of my own, one of which carried me deep into the hill country near Boerne, and during several wistful hours watching and reading about The Exorcist.

It had been just a little more than a year since Malcolm first told me that Cotton Mather hadn’t been all wrong. Then Malcolm had been alone. This time there were two other church fathers in the office with us. The eldest, a dark-haired, heavy, slow-moving, bifocaled country gentleman of about 50, shrewd, stable and decided as a rock, had already warned Malcolm once about saying something he was “not sure of.” So this year, and it’s also true that times have changed, Malcolm said that the Salem witch-hunters had been mistaken, not for pursuing witches since, of course, that was right, but for physically punishing the afflicted. “The trouble is spiritual,” he said, “so you have to work on their spirit.”

I was glad to hear it. I had expected all in all a much more nervous meeting and a more urgent, strident tone, since at our first meeting thoughts of the power of witches had been very much on his mind. Nothing in the past sixteen months should have lessened that fear; sex, satanism, and witchcraft were more than ever subjects that set the national lips to wagging and kept certain books, magazines, and movies selling. Satan had become so strong, if the president’s chief advisor is to be believed, that He now has the strength and audacity even to attack tape recordings made by the highest office in the land. Yet Malcolm’s face was relaxed, much happier looking, more the way I’d seen it look one Sunday morning when he’d led the congregation in a hard-driving hymn, arms waving and his body going up and down in rhythm. Things had returned to their usual ominous normalcy.

Malcolm and I had first met as a result of my reading in the San Antonio paper that Malcolm’s church, the Castle Hills Baptist, would hold a book-burning in its parking lot Halloween night. Typically I had read the paper several days late and consequently missed the event. But I might not have attended anyway, since the story also contained the fascinating news that the church believed that same Halloween night (1972) would see a meeting in the hills near San Antonio of all the most powerful witches in the world. And this was to be no yearly read-the-minutes, old business, new business, motion for adjournment, dull-as-dirty-laundry meeting. They were going to receive the 23-year-old anti-Christ himself, whose appearance there that night had been scheduled—alarmists were using the word foretold—at the last meeting of the world’s most powerful witches twenty years earlier on the Isle of Man. The book-burning was to be a rally of spiritual vigilantes whose opposition to the witches was to be both proclaimed and aroused. The situation was critical; ill winds were blowing through San Antonio. The church had it on good authority that groups of local high school students were drinking blood in secret rites. Not human blood, they said, but still blood!

I imagined the Halloween book-burning: searing flames, twelve feet high, toward which move slow solemn lines of those once tempted but now savedÑtheir arms full of Rolling Stones records, Edgar Cayce biographies, horoscope charts, lewd novels, Marvel comics, magazines with lascivious photos of Chicago whores luring farm boys, Ouija boards, tarot packs, psychology textbooks, left-wing political pamphlets, hare krishna incense, all objects declared evil and therefore cast into the rising fire. And yet how much more eerie would the witches’ meeting be! What would they cast into the fire?

All that seemed like a good measure of fantasy to come from one newspaper article. It stayed with me long enough that in late November I drove down to see what the Castle Hills Baptist Church looked like and to see if I could find any witches who’d hung around after the big confab.

Rather to my surprise Castle Hills really did have hills. It’s a new, comfortable development just north of Loop 410 in northern San Antonio. The streets are quiet, the houses medium-sized to large, and surrounded by enough trees and grass to have absorbed any sterile newness.

The church is as new and as impressive as the community it serves. There are several buildings: a white wooden bungalow which holds a day care center, and behind it, two much larger stone edifices holding offices and chapels, a choir rehearsal hall, meeting rooms, even a gymnasium. The church complex occupies several acres at the top of a hill with grass lawns, some venerable old trees, and parking lots big enough for hundreds of cars. It would take a dedicated, practical, and far from destitute congregation to build such a church. Their concern with witches could not, at least in the local religious community, be easily ignored.

I had an appointment with Malcolm Grainger, the church’s minister of music, and was led to his study down hallways with shining linoleum floors and plaster walls painted brown, through shellacked doors with brown metal frames and oblong windows at eye level. The fluorescent lights were turned off in the hallway leading to Malcolm’s office. The hallway was long enough and dark enough to be a little frightening, but a door at the opposite end opened on a brightly lit rehearsal hall where lifters were still stacked in ascending tiers. Just off to the right, in his office, Malcolm was waiting.

He was not as big a surprise as Castle Hills itself had been. His hair was oiled and neatly combed straight back from his face. The hair, his broad forehead, and his teeth, often visible as he spoke, were his most distinguishing characteristics. The rest of him—his eyes, his jowls, his chin—seemed grey, difficult to see. His features made Malcolm look younger from twenty feet away than from ten. And from ten feet he could have been 35 or 40 or 45. Depending on which it really was, a life in the church had made him age slowly, at a normal rate, or faster than usual.

We shook hands across his desk, concern on both our faces. He remained behind his desk and I took a chair on the side opposite him. “I came down here,” I said, taking out a notepad and pen with a fair amount of flourish, “to find out what’s been going on. The papers said something about a big meeting of witches last Halloween?”

Malcolm nodded gravely.

“How’d you find out about that?” I asked.

“There have been signs something was going to happen in San Antonio for a long time,” he began. And then he immediately started telling me about one John Todd, a man about 28, who had come to Castle Hills with the story that he was a former grand druid, one of the ten or so highest ranking witches in the United States. Todd had been converted just six weeks earlier after seeing the movie The Cross and the Switchblade. He had then made his way to Castle Hills with his story of the world meeting Halloween night. Todd added that his occult name was Lance, that the meeting would be attended by Anton LaVey, high priest of San Francisco’s Satanic Church, by Jeanne Dixon, by the Amazing Kreskin, by representatives from the Woman’s International Terrorist Conspiracy from Hell, by a voodoo priest from Brazil, and possibly by representatives from the World Council of Churches and the Vatican. Todd claimed he feared for his life now that he had converted—his past associates would stop at nothing—but his list of witches, in spite of the great secrecy he insisted surrounded all their doings, sounded like pretty much the same people David Susskind would choose to gather for a TV show on the occult. But Todd’s paranoia ran full depth: Nixon had consulted astrologers while in China, proving his connection with the black arts, and George McGovern was a member of a Chicago coven where he used the name Lanaca.

The church had bought the whole story. “I was skeptical at first,” Malcolm told me, pointing his forehead straight into my eyes, his reedy voice gaining in timbre, “but I’ve prayed with him and heard him testify. There’re too many other things happening that all point to this. John even has a scar on his arm from the time he sealed a covenant with Satan with his own blood.”

Blood again. Malcolm would later tell me he had claimed his office with the blood of Jesus Christ to protect us from the devils that would surely come around when we started talking about them. Malcolm watched me warily; I tried without completely succeeding not to watch him the same way.

Malcolm’s office ran about fifteen feet on a side, had a carpet, a comfortable couch, several chairs, a five-foot desk. He sat before a large window flanked by built-in bookcases filled with biblical reference books and Christian tracts. The sun was shining through the window making the office light as outdoors and, as he talked, my eyes sometimes drifted to the hard blue November sky above his head.

“They’ve chosen San Antonio,” Malcolm went on, “because of the water around here, they need it for their rituals, and because the climate and everything else is like Palestine.” In fact Todd had said that the witches were going to build a temple. It would have a rounded top with bulletproof glass and doorways with no doors that still keep in heat in winter and cold in summer and a stained glass window with a pentacle and a cross. There would be one story above ground and four below. It would have some noncommital name so the general public wouldn’t know it was the world headquarters of witchcraft although the general public would all agree it was a very beautiful building.

No wonder everyone was so upset. Todd had even warned that witches were infesting the humane society so they would have access to animals to sacrifice in their rituals.

Todd’s warnings had not been seeds cast upon rocky soil. Satan, Malcolm believed, had been making his presence felt in San Antonio for some time. One of the first cases he had himself seen was that of a Mexican man who complained of hearing voices, of feeling that he had fouled his pants only to discover that he hadn’t. He felt parts of his flesh burning and was beset at night with grim visitations. The man went to a curandero, a Mexican sorcerer, who gave him a potion to rub on his flesh when it burned.

That treatment failed. Through a relative the man came to Castle Hills and Malcolm prayed with him to cast out the devil. The man admitted he was homosexual. He thought the spirit inhabiting him was in the form of a woman who made him seek out men for her. Malcolm allowed no other explanation but possession for either the man’s behavior or sexual preferences.

“I’ve always wondered how homosexuals can come into a new town where they don’t know anyone and very quickly find others like them,” Malcolm explained. “It’s the devil in them that draws them to others that are possessed. Satanists can recognize each other the same way.”

“Humanism, science, rationalism, are really the work of the devil because they tell us not to believe in devils and spirits and that makes us all the more susceptible to them.”

It was difficult to know what to say next. Fortunately, Malcolm was used to taking the ball and running with it. “Humanism, science, rationalism,” saying them as if he were spitting out bad tasting seeds, “are really the work of the devil because they tell us not to believe in devils and spirits and that makes us all the more susceptible to them.” Then he leapt into the breach with proof. He pulled a file from his desk which contained, among other things, clippings from a 1971 copy of the Village Voice. The clippings were all the ads that had anything to do with meditation, eastern religion, Gestalt therapy, psychotherapy, astrology, drugs, plays and movies about sex; a play called “Sodom and Gomorrah” had him particularly upset. He showed me these ads one by one with great solemnity, but never letting them out of his hands and watching me carefully to gauge their effect. He was peculiarly silent during all this. Then he mentioned with horror the television show “Bewitched.” He said that you could walk into any bookstore and see hundreds of books on demonology, witchcraft, Satanism, eastern religion, etc. All these things, he said, were produced by either willing or unwitting cohorts of the devil. Allowing them in your house was simply giving Satan a door through which he could pass into your soul.

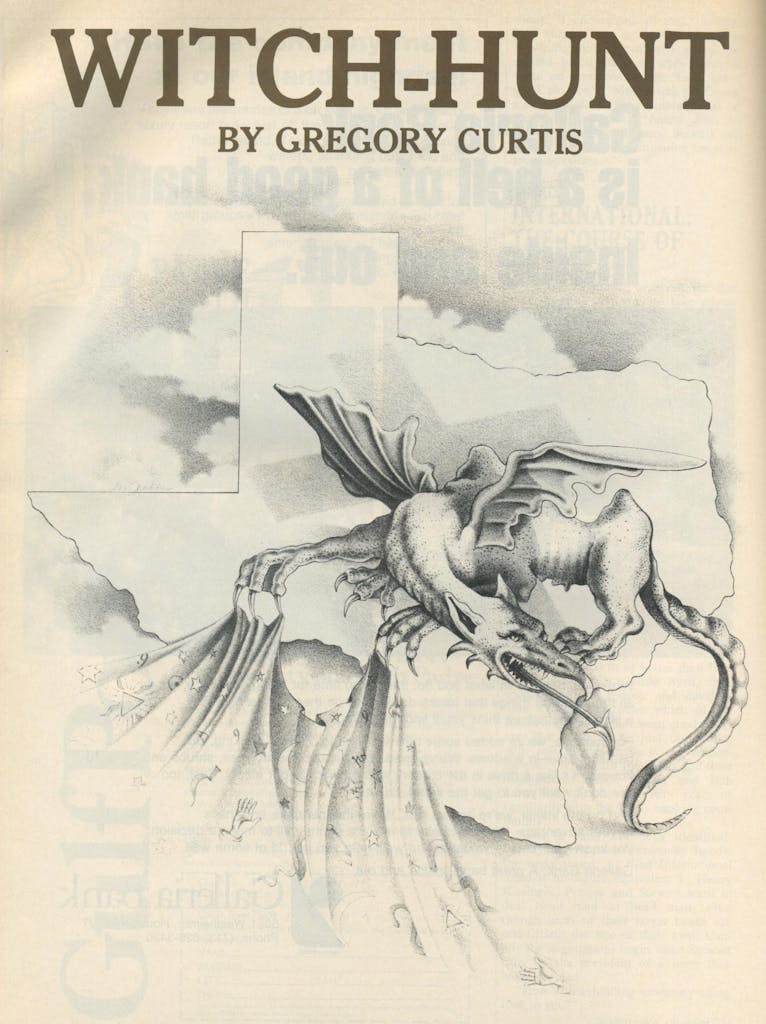

As final proof he pulled from his file a Marvel comic called “New Gods.” He pointed to a picture of an immense hairy monster with tentacles streaming from its mouth. “This is close,” he said. I didn’t understand. Malcolm and I glanced at one another but said nothing. He turned to another, larger picture, placed it in front of me, and tapped the edge slowly with one finger. It was a picture of a swarm of scaly devils riding screeching pterodactyls toward a frenzied, helpless man. “This is very close,” Malcolm said. And then I understood.

There was more but he stopped as two women joined us in the office. He placed the folder back in his desk and with a smile now back on his face, introduced me to the women.

They were the youth minister, a tall white-haired woman in her fifties, very unlike the “dynamic,” well-dressed student council types youth ministers tend to be, and a much younger woman with curled, beauty parlor hair, hose, heels, a nondescript though relatively new red and blue dress. Attractive enough in an oval, fresh-faced, hearth ’n’ home way, she was in charge of the church’s day care center. She believed that many childhood difficulties—anger, frustration, disobedience—can be attributed to demon possession. “We can pray and get rid of the demon,” she said, “but it doesn’t do any good if the child goes right back to a house where devils exist.” It seemed likely that a child who threw a tantrum and had to suffer through a long bout of prayers because of it might think twice before throwing one again. “I used to be possessed with the demon of self-pity,” she said, her perky voice assuming a kind of perky sincerity, “but I was able to rid myself of it through prayer. And now—she sat up straighter, smiled happily, wrinkled her eyes— “I’m not bothered with self-pity any more.”

John Todd had said that San Antonio high school students were drinking dog’s blood in witchcraft ceremonies, and the youth minister concurred. She said that a girl in whose home she was regularly visiting admitted that she had been involved in something like that. The principals of the high schools mentioned had been notified and given the names of the girls supposedly involved. It’s interesting to reflect that the Salem trials began with adolescent girls accusing people who for one reason or another they didn’t like.

And there really had been a book-burning. Malcolm’s account made my imagined scene seem pretty close to the truth.

Many objects of the devil had been burned. The high point had been the arrival of a girl dressed in black robes who said she had set out that Halloween night to have sex with Satan. What perverse strain of that erotic desire had led her to Castle Hills would make interesting speculation. But show up she did. Later she said, knowing there were rabbits in the woods behind the church, that she thought she was taking the form of a wolf; she wanted to find the rabbits and drink their blood. According to Malcolm, several strong men had to hold her down so they could pray over her and exorcize the devil in her.

John Todd, unfortunately, could not be seen. He was frightened that his old cohorts in witchcraft were plotting revenge for his exposing them. “But go see Jim Dolan,” Malcolm said. “He’s a reporter, too. He knows about these things.” Finally Malcolm gave me some tapes, one by Todd telling about his escape from witchcraft and another from a woman who, right in this same office, had been delivered from Satan and seen visions of Satan and Jesus while it happened.

As I rose to say good-bye to the three of them, Malcolm asked, “Are you a Christian, Greg?”

“Uhhh, yes.” I was by cultural tradition at least.

“Praise the Lord for that!” he said. “You know you’re going to be in danger.”

“Well … yes … thank you.” I held out my hand to the youth minister.

“Praise the Lord,” she said looking at me expectantly.

“Yes . . . thank you.” I held out my hand to the young woman who ran the day care center.

“Praise the Lord,” she snapped.

“Yes . . . thank you. Thank you all.”

Thank you?

I walked down that long, dark corridor to my car. Unless San Antonio concealed a whole legion of witches, what had really happened was this: a single itinerant, John Todd, had brought about one of America’s rare, frightening book-burnings. Right then he looked more powerful than any witch.

I had been glad to hear Malcolm mention Dolan since he had written the first stories I’d read about this strange phenomenon. He turned out to be someone I liked immediately—tall, fresh-faced, serious, very much aware of himself in his role as reporter.

We had hamburgers in a restaurant along the river. Dolan had earlier asked me, “Do you believe in all this?” When he saw me hem and haw, not knowing where he stood, he volunteered, “Because I don’t believe a word of it.” It made me trust him as a sensible man.

But all writers, and especially reporters, are men of imagination; by the time Dolan and I were half way through our hamburgers his imagination, earlier left behind while we poo pooed the whole thing, had caught up with him. He began telling me about the string of witches he’d interviewed in San Antonio.

They were pathetic, isolated, lonely little people who usually had followings of a friend or two or three. They glorified their meager activities with occult mumbo-jumbo and, far from presenting a united front against Jesus’ people, they each accused the other witches of straying from the true path.

Maybe the voodoo priest did do something strange that night. Maybe the lights in that fifth floor really were silently witnessing an exercise of black arts.

Nevertheless, not quite everything could be so summarily dismissed. The only would-be witch capable of holding together a coven also owned a building near the river. On Halloween night Dolan had seen lights all along the fifth floor of that building. “Now what does that mean?” he asked me and went on without waiting for a reply. “It may mean nothing, may be just coincidence, but we do know this: the elevator in that building doesn’t stop on the fifth floor.” Like a good reporter he had gone the next day and discovered this fact while posing as a potential cheap apartment renter, a role newsmen easily and frequently assume.

There had been other strong occurrences. Dolan’s it-may-mean-nothings became less forceful while his we-do-know-thises became sudden, direct, and confident. But we do know this—the Brazilian voodoo doctor was not in his hotel room that night. And we do know this—that strange girl who said she was a witch didn’t come home ’til way after midnight. “But . . .” he said at last, “I still think it’s just a lot of baloney. There are just a lot of strange things connected with it.”

So. It appeared there were real wackos running around loose in San Antonio—witches, bookburners, and even reporters chasing after them with pencils ready. The high school girl had said her friends were drinking blood. It sounded like something anyone might tell an elderly woman minister who kept dropping around. But on the other hand maybe they did. Maybe it was exactly the young girl whose family was most influenced by the church who would become interested in Satanism, just as a child told never to open a particular door finds opening that door ever more appealing. Maybe the voodoo priest did do something strange that night. Maybe the lights in that fifth floor really were silently witnessing an exercise of black arts. It was at that point that Dolan told me one of the girls he had been talking to might tell him where and when the next great witches’ celebration would be held.

“You’ve got to find out,” I said.

“I will. I will.” No reporter speaking to another reporter could have said less.

And he did find out.

As I drove toward Boerne where I was to meet Dolan the sky changed from grey to greyer and the temperature dropped enough for the cold to stop being a curiosity and start jabbing like something real. It was the winter solstice, the longest night of the year, and a dark, dismal one to spend waiting for witches.

The meeting—or ritual or black mass or celebration or sacrifice or whatever else it might be—was supposed to happen at a place called Edge Falls, a genuine waterfall a ways east of Boerne which, when it wasn’t the setting for practicing black arts, doubled as a swimming hole. Neither Dolan nor I had ever been there, but he had some vague directions. The place was supposedly surrounded by woods, so our plan was to watch the whole thing concealed behind trees, then rush back home to write our stories. Provided we were able to rush back home. Dolan had mumbled a little something about bringing a gun just in case.

It was only slightly more than a week since I’d made the trip to see Malcolm. In the meantime I’d played the tapes he’d given me. Todd’s tapes, which he called “Lucifer’s Legions” and “From the Pits of Hell,” were as preposterous as their titles. Judging by the tapes, Todd knows nothing about witchcraft that couldn’t be learned for the price of a cheap paperback. He had evidently discovered how to make a little knowledge go a long way.

…the tape by the woman who had been delivered radiated real conviction… everything pointed to her genuine belief in the visions she has seen and still sees…

But the tape by the woman who had been delivered radiated real conviction. I met her more than a year later and once again everything pointed to her genuine belief in the visions she has seen and still sees and in the voices she frequently hears; at the same time nothing but her belief says they really are there. She’s a slight, birdlike woman in her middle thirties, born a Jew and still active in the synagogue although she has by now been baptized in the Pentecostal church. She lives according to her modest means with her husband and two children in a small bungalow in a new development in northern San Antonio. All her life she has heard voices talking to her and felt from time to time hands on her, and has felt she knew what people were going to say before they said it, as well as having ESP and out-of-body experiences. It would be possible to spend quite a bit of time speculating about all this; but what ran through my mind as I drove toward Boerne was her account of her deliverance from the devil in the very office where I had spoken with Malcolm. She said the angel Michael had torn Lucifer from her after a long bout. He’d had a lizard body, green scales, forked tail, claws. Then she had seen Christ on the cross and behind him the buildings of a great city and she had the feeling of all the centuries past and present joined together behind him. Then she saw black and white clouds battling one another and when they had cleared she saw Christ again, his head bowed, wearing a grey robe, grey it was later revealed to her because our sins muddied his raiments. Heady thoughts for a drive to Boerne.

I met Dolan in the parking lot of the Antlers restaurant right at dusk. We shoved another quick hamburger down our throats and started toward Edge Falls. I had a singular impression of greyness as we drove deep into the hill country, not only from the sky, but also from the road, the leafless trees, the rocky stubble-covered ground, even from the wary deer we could occasionally see nosing among grey rocks. The sky seemed heavy, close to the earth, and we plowed through the lingering dusk and then through the early night without saying much to one another. Apparently Dolan had decided against a gun in favor of a thermos of coffee, a sensible decision all in all and one I approved of. But what if we did get into a tight spot?

By the time we got where we thought Edge Falls ought to be, it was quite dark. We stopped to ask a man who ran a shop that sold everything from pickled pigs’ feet to toilet floats where the falls were. He pointed and said about seven miles farther on we’d see a sign where we should turn. We followed a paved road, carefully checking every possible turn, until about ten miles later our road joined with a major highway. We stopped at a filling station where the owner told us the falls were about seven miles back the way we’d come. Satan couldn’t have planned it better. We went back and forth across that ten mile stretch of road, flashing our lights around every turnoff, forging down gravel roads then scurrying back with our heads down low hoping the rancher our noise had disturbed wouldn’t start shooting. Aggravation! Finally, back at the toilet float shop, we noticed, just a few yards off the road, a huge hand-lettered sign, partially obscured by the darkness, reading Edge Falls. An arrow pointed down a dirt road that ran perpendicular to the paved road we’d been on. Dolan and I looked at one another, shook our heads, and started on.

It was already well past ten. The ceremony wasn’t supposed to start until midnight but we wanted to get there enough ahead of them to get the car out of the way and find a safe hiding place for ourselves. While we hadn’t been especially worried about time all the while we were fruitlessly searching up and down that road, now that we were on the right track, it seemed like we should get there as soon as possible. I pushed the car to 65, supersonic speed for the bumpy country road we were on, and found myself sliding to a dusty halt just two inches shy of a stone wall beside a narrow cattle guard.

After that I slowed way down, but the near accident had broken the confident veneer Dolan and I were affecting for one another’s benefit. Sudden noises from the dark woods made us catch our breath. An odd reflection in the headlights made us stop to warily investigate; we found nothing and that became ominous. But sure enough, seven or eight miles into the woods, we found another large sign, lettered by the same hand as the first one, which announced a left turn for Edge Falls and a dollar charge. We stopped by the turnoff which was nothing more, at least as far as we could tell in the dark, than a short access road leading to a small cabin now lit with a yellow bulb above a plank door. Somewhere in the woods beyond the cabin we could hear the sound of rushing water. We had arrived. Now what?

I don’t know which one of us thought of the plan or why it seemed so logical at the time. What we did was drive back about twenty yards where there was another, smaller dirt road, back onto it, cut the motor and the lights, and wait for something to happen. We were literal-minded enough to assume the witches would not fly in but have to come down the same road we had. At that point we would get out of the car and secretly follow them on foot.

Dolan and I sat for a while staring into the darkness. It was so dark I couldn’t see the hood ornament on the car. It was so quiet that we spoke in whispers as we passed the thermos back and forth. We could not see one another in the darkness.

“You ever get tricked into going on a snipe hunt?” I asked him.

“Oh yeah.”

We told snipe hunt stories for a while, then the conversation sagged, dwindled, ended. It was dark everywhere, as if black velvet had been cast across the world. The sudden, though quiet, forest sounds, the hoots and rustlings and soft whistles, were the kind of noises movie plainsmen can always identify as animal or enemy. We could not tell that difference. Was that an armadillo poking among the underbrush? Or was it something else, someone, creeping toward us through the darkness? The beasts of the forest night we could contend with. We sat in silent fear of our fellow man.

And that, I realized, was just what a witch would have us do. Witches were real, all right. They hid in the puniest, most fearful regions of the soul. But expecting to find witches at Edge Falls, real witches, made as much sense as chasing after snipe with a gunny sack. I started the car and drove down to the cabin on the way to the falls.

We stopped by a tall fence fifteen yards from the cabin door. A small, thick man, country as a bluetick hound, stood just inside the cabin.

“We heard there was going to be a religious service down at the falls,” Dolan shouted at him. “Seen anybody?”

“Naw, I ain’t,” he shouted back. “If I do I’m gonna run ’em off jest like the last bunch.”

“What last bunch?”

“Last Hal’ween. Two ’er three a them weirdos showed up an’ wanted to get down to the falls. I told ’em to take off them silly costumes an’ git on home. Bunch a damn fools is what they was.”

Evidently one old country codger had stopped all the minions of hell John Todd had prophesied. God works in mysterious ways.

That was in late winter 1972. I had pretty much placed the story on the back burner after the Edge Falls fiasco. The people who had told Dolan about the meeting said they had all been there, but we just couldn’t see them. Fine. It seemed to be a good time to quit for everyone concerned. But seeing The Exorcist brought the whole experience lumbering back again.

With the exception of The Sound of Music, The Exorcist is the most financially successful horror movie ever made. It is a movie with absolutely no merit except that it has seized on the one gimmick essential to successful horror films—the creation of an evil force the audience can believe is real. Many people believe the devil does, or might, exist. If he exists, why couldn’t he take possession of a little girl? And if he took possession of her, why not … of you? From that point special effects and makeup do the rest. But tastes in evil are fickle as tastes in clothes. Remember that King Kong, which is a bundle of laughs today, was truly frightening to the audiences of its time. The Exorcist, too, will become such a joke, though a decidedly less enjoyable one.

But that will be then, and now is now. As I drove back from seeing the movie, looking for a gas station that had something to sell, I heard on the radio that a man in Mississippi, following what he took to be the instructions of a voice from God, murdered six members of his family. It occurred to me then that things might have gone from frantic to hysterical in San Antonio as well.

I was both disappointed and relieved to discover, as I mentioned in the beginning, that the situation at Castle Hills was more relaxed. Book-burnings, though they were hardly to the point of being regarded as skeletons in the closet, were at least not in the plans for the immediate future. No more talk about the young anti-Christ—suspicion now had it that the anti-Christ is Henry Kissinger. I asked Malcolm about the temple the Satanists were supposed to build. “Well, John Todd called me from California and asked if I’d seen the Unitarian church being built here.” And that was when he was warned about saying things he wasn’t sure of. (There is, as a matter of fact, no Unitarian church being built in San Antonio.) The church had been had, but belief was not shaken. The older, placid minister I mentioned at the beginning told me he had seen men possessed crawl on the floor and howl like a dog. This minister had a practical, down-home air about him, the kind of man who would know both a good cold remedy and how to wire a house. Yet this otherwise down-to-earth fellow found the devil’s hand in behavior I would tend to pass off as the result of strong drink, an extra Y chromosome, or too much television. It reflected a deeper division than a mere difference of opinion. We did not take to one another.

Looking for witches is like looking for murderers or saints—the real ones won’t come forward.

And witches turned out to be in very short supply. Looking for witches is like looking for murderers or saints—the real ones won’t come forward. It may be there is a genuine, hard-working witch-craft cult in San Antonio, picking up new members, meeting regularly, casting spells, the whole bit. But I doubt it. The few I ran across are pretty much the kind of people witches have always been from the very beginning right up until last year—the lonely, the lost, the disoriented, gathering a follower or a friend here and losing him there. Let them go their way. They would be completely negligible if their mere presence didn’t inspire book-burnings on church parking lots.

My two separate witchhunts had fizzled and the church that inspired them was taking a lower profile on the subject. So what is to be made of all this? I offer only this moral: in Ceylon, where firewalking is a semi-religious act thought possible only after long meditation and abstinence from meat and alcohol, a group of non-believers claimed it was merely a layer of ash over the coals that made firewalking possible. They ate meat, drank, did not meditate. They walked through the fire unharmed. And were set upon immediately by the religious for desecrating the shrine.

- More About:

- Longreads

- San Antonio