One Friday evening last fall I went to hear a young Texas musician named Pat Green. At the time, the only thing I knew about him was that he sang country music. I hadn’t even heard of him just a few days earlier, when I was having lunch with some of my colleagues. I had launched into one of my speeches about how the new generation of Texans, age thirty and under, didn’t seem to care about Texas anymore. They were too homogenized, I pronounced. They were conditioned on the basic diet of cable television and standard pop music that made them no different from anyone else their age in other parts of the country. They didn’t have any sense of the Texas myth, I continued, my voice rising, and even worse, they didn’t care about acting Texan.

“Obviously, you haven’t heard about this Pat Green phenomenon,” said someone at the table.

“Pat Green?” I asked.

“He’s got a following among Texas kids that no one can explain.”

When I called Green’s managers, they told me that his next performance would be at Jesuit High School, a private Catholic boys’ school in the heart of North Dallas, not far from my house. “Jesuit?” I asked. The boys I knew from Jesuit were the prototypical new-Texas urban teenagers. Many of them were the sons of high-tech millionaires, downtown lawyers, and venture capitalists who themselves didn’t come to Texas until after they had completed their college education in prominent Eastern schools. These boys were drawl-free. They didn’t feel a need to drive pickups or use agrarian homilies. They didn’t know what a pump jack looked like, and they didn’t dream about ranches. They wore baseball caps, not gimme caps. Yet for the party that was being held after the homecoming football game, these kids had persuaded their parents to hire Pat Green.

I sat at a table in front of the stage with some parents and prominent alumni. The Jesuit boys and their dates—snazzily dressed girls in spaghetti-strap tops who attended other North Dallas private schools—were packed into the surrounding risers. Their eyes were locked on the stage. As they waited for Green to come out, they began chanting his name over and over.

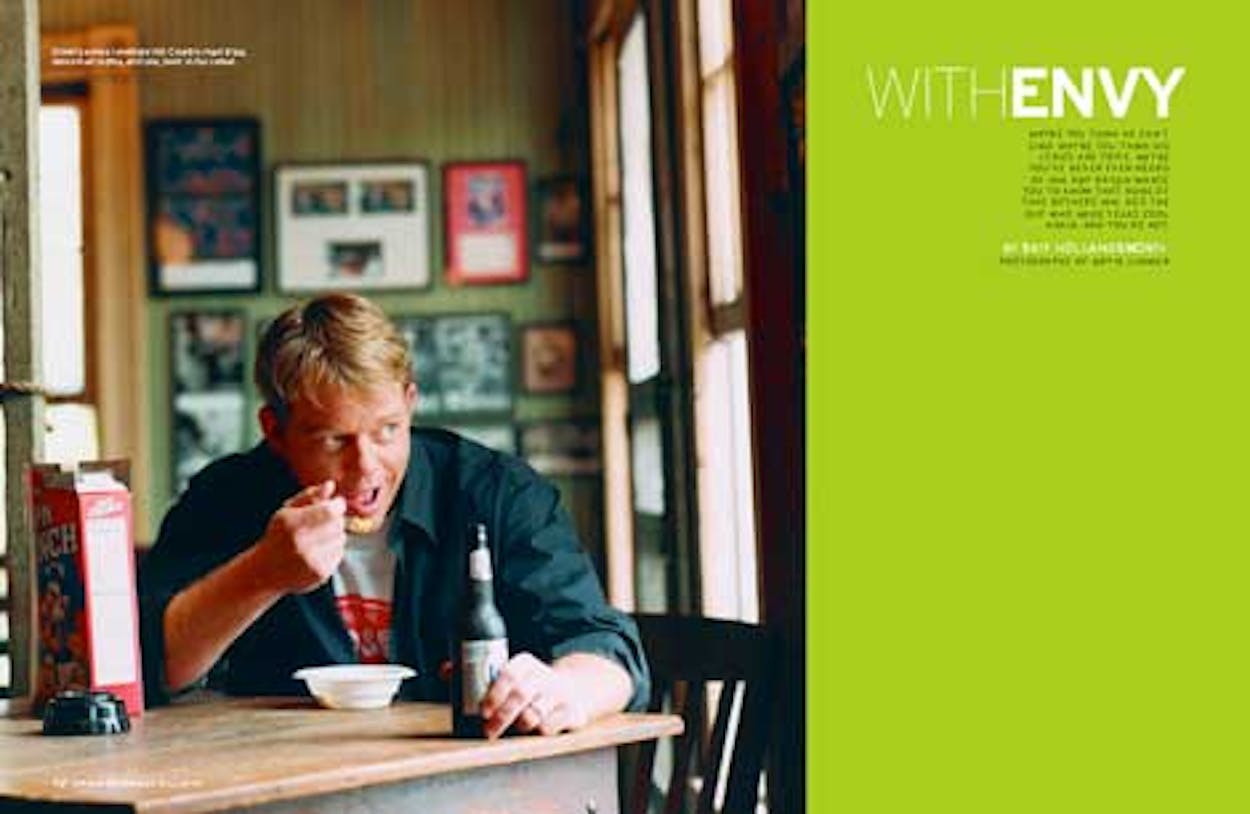

Then he appeared, an average-looking young guy with short blond hair and a big grin. He was wearing an untucked blue baseball undershirt beneath an untucked flannel snap-button shirt, blue jeans, a faded baseball cap, and old-fashioned Justin work boots, which he kicked off almost as soon as he got onstage. “Here we go,” he shouted, and his band launched into a rollicking tune that began, “Now up and at ‘em, here we go. / I’m off again to the rodeo.” Suddenly from the risers came a wall of noise, a wild adolescent tumult that made me turn completely around in my chair. The concert was only seconds old, and already all of the kids were either screaming or singing every word of the song along with him. When he got to the line “Here I go again just singin’ in this dive. / Lone Star beer in my cereal is keepin’ me alive,” the kids were singing so loudly it was hard to hear Green himself. They kept singing when he got to the line about living “back in the times of the Dukes of Hazzard, / Listening to Willie and old Merle Haggard,” and they literally shouted at the top of their lungs along with him as he sang about the warning his mother gave him about Copenhagen snuff:

“That shit is gonna kill you if the women don’t get you first.”

The adults, many of whom had also barely heard of Pat Green, began trading quizzical looks. How in the world was this happening? The singer was not handsome in the music-star sort of way. He had no chiseled jaw or tight-fitting Wranglers to show off his butt. In all honesty, he looked like the typical guy you see at almost any college bar around Texas, the one who’s a little chubby and as cheerful as a big, frolicsome dog, drinking lots of beer, pounding people on the back, singing along with the jukebox, and telling everyone he needs to get home to study for a test—even though he, and everyone else, knows he’s not going anywhere. But as Green rambled around the stage, his shirttail flapping, his head tossing back and forth in time to the music, the teenagers acted as if he were the next coming of Bruce Springsteen.

“Yeah, I like Texas. / Ain’t it fine here?” Green sang. “Like to pick my guitar down in Luckenbach / And drink that Shiner Bock beer.” Once again, the kids roared. “How,” I asked myself, “do these students even know what Luckenbach is?” Up came another song: “I woke up this morning, Texas on my mind / Thinking about my friends there and a girl I’d left behind / The way she held me when we kissed, the loving that we’d done / And how I left her waving good-bye standing in the Texas sun.” I turned around to stare at the boys of Jesuit pumping their fists into the air.

The next day, my seventeen-year-old stepdaughter, Hailey, took a few minutes away from one of her marathon telephone conversations with her boyfriend, walked into the kitchen, and said, almost reverently, “Mom told me you saw Pat Green last night.”

“You know who Pat Green is?” I asked.

“Oh, my God, do you not understand that I play his CD driving to school every morning? That everyone who parks on Senior Row [the parking area reserved for seniors at Dallas’ Hillcrest High School] has to hear his song ‘Three Days’ before they begin their day?”

I could feel my mouth falling open. Hailey is the kind of girl who studies photographs of Cameron Diaz to pick up fashion tips, watches The Real World on MTV to understand the intricacies of human behavior, and then disappears into her bedroom to brood over the injustice of not having met any of the male cast members of Dawson’s Creek.

“You have a Pat Green CD?” I asked. “The guy who sings country songs about Texas?”

“Um, hello, like, where have you been?”

Where have I been?

And where, for that matter, have you been? If you’re over the age of forty, there’s a good chance you too have little idea who Pat Green is. Even those of you who think you stay abreast of country music might not know much about him. Completely under the radar, the thirty-year-old has become a gigantic force in country music in this state, his audience consisting of an almost absurdly enthusiastic horde of fans, most of whom are white teenagers, college students, and young adults in their twenties and early thirties. Between mid-February and mid-April of this year, more than 180,000 fans showed up at concerts in Texas to see him. The 6,000 tickets to his performance at the cavernous Billy Bob’s nightclub in Fort Worth sold out in 35 minutes. The only singer who had sold out Billy Bob’s in less time was Garth Brooks, in 1991. At South Padre Island, where Green is known as the king of spring break, his two shows drew 14,500 beer-guzzling, yeehawing college students. Some 30,000 fans turned out in the rain to see him perform at Chilifest near Texas A&M, in College Station, and more than 56,000 people watched him at the Houston Rodeo in the Astrodome. Among the country acts performing at the rodeo, which ran for twenty days, only George Strait and two shows that featured a variety of Nashville stars outsold him. Green, in turn, outsold the Dixie Chicks, Willie Nelson, Alan Jackson, Clay Walker, Lyle Lovett, Brooks and Dunn, and Clint Black.

On his own, with little advertising and less radio support, Green has sold more than 255,000 self-produced, independently distributed albums, an amazing number considering that almost all of those sales have come from within Texas. Last year, when he finally decided to go national, cutting a major-label deal with Republic Records (a subsidiary of Universal Records), his album Three Days entered Billboard’s Country chart at number seven. That was also mostly due to the album’s sales in Texas. Brian Philips, the senior vice president of Country Music Television, is so hooked on Green that two of his videos, “Carry On” and “Three Days,” are on the playlist, alongside the videos of such standard Nashville names as Tim McGraw and Shania Twain. And to top it all off, Miller Lite has hired Green to appear in a series of commercials, in which he picks at his guitar and talks about his life playing music in Texas. (The first spot aired on CBS in March during the NCAA basketball tournament.) “In the grand pantheon of Texas country music,” Dallas Morning News country music critic Mario Tarradell recently wrote, “Pat Green has emerged as a modern-day messiah.”

Yet for many music critics, Green’s success is simply bewildering. It’s not the fact that he refers to a Texas of old; it’s how he does it. They say that Green does little more than sing about tired, overused images—road trips down Interstate 35, beer-and-taco dinners, Luckenbach, Gruene Hall, and the love of a good Texas woman. Evoking the revered Texas singer-songwriting tradition that has produced such profoundly poetic writers as Townes Van Zandt and Guy Clark, Nelson and Lovett, reviewers have called Green a derivative songwriter with nothing original to say. Rob Patterson, a critic for the Dallas Observer and the Houston Press, not only wrote that Green’s music was “stunningly mediocre” but also described him as “Mr. Potato Boy with a battered cowboy hat.” Robert Wilonsky, who also writes for the Observer, argued that “Green writes his songs for the Lone Star circuit, milking the native audience’s deep-in-the-heart flag-waving to collect his wooden nickels” and that his act is no different from the cheesy Texas-shaped ashtrays that are for sale at an airport gift shop. “Yee-haw, ya phony,” snapped Wilonsky. The reviews have been so vicious that the Austin American-Statesman’s Michael Corcoran wrote last year that Green had become “the most reviled Texas artist since Vanilla Ice.”

“Look, I’ll be the first to admit that I’m not the deepest songwriter in the world,” said Green, giving me a congenial shrug when I visited him recently at his home in the Tarrytown neighborhood of Austin. He and his wife, Kori, a very pretty and very smart third-year law student at the University of Texas, had just moved in, and Kori was in the living room with friends, laying down a new rug. Green, meanwhile, was sitting in the back of the house in his office, which he had decorated in what he called “basic guy.” On his desk was a computer, which he used to play computer golf. On one wall was a drawing of Pancho Villa, a photograph of Louis Armstrong, and a medallion that read “Pat Green, Texas songwriter”—about the only evidence that suggested Green was a musician at all.

“My songs don’t get real dark about the human condition,” he said. “But there are a lot of people hearing these songs and saying, ‘This guy is speaking to me. This guy is singing about a life I like living, or I want to live.’ So how do you explain that?”

How does one explain it? Even if the critics are right about Green’s Texas-centric lyrics, what many of them are missing is the extraordinary impact this music is having on a new generation of Texans. Although his audiences include plenty of gun-rack bubbas and young rural-looking women with sprayed, crunchy hairdos, he is also drawing an incredible number of J. Crew fraternity boys and urban babes whose $60 Toni and Guy trims are hidden under cute cowboy hats. Green’s fans call themselves Green Heads, they joyfully scream “Pat F—ing Green” whenever he comes onstage, they wave their baseball caps and cowboy hats in the air, and with a yahooish fervor they greet each song with farmhand-style shouts, though it’s likely that many of them have never been on a farm. For them, Green is an accessible country music performer: His voice is not overly twangy, and his music is inspired as much by rock sensibilities as by steel guitars and George Jones. But above all, it’s the message, according to Casey Saliba, a freshman at Southwest Texas State, in San Marcos, who also happens to be dating my stepdaughter. “He isn’t like those old country music singers you listen to who sing about problems with love and divorce and going broke and all that old people’s stuff,” Casey told me one day as he dug through my refrigerator, looking for food.

In fact, Green is a Texas version of Jimmy Buffett, a good-natured guy who looks like most of the men in his audience, who takes off his boots and plays barefoot, and who bangs out easy-to-sing-along songs about the Lone Star State as a laid-back, freewheeling paradise where you can have more fun than you ever thought possible and where you deal with your problems by going on weekend road trips, drinking a little beer, and visiting classic Texas landmarks that many of these kids never knew existed. In his hit “Carry On,” Green sings: “Baby’s just a little bit tired of the city. / Billboards and bullshit got her down. / Seems like you need a little Hill Country, / A little back roads drivin’, / A little bit of that old top down.” Critics might cringe, but an assistant program director for KPLX-FM 99.5, the Wolf, a Dallas country music station, told Billboard magazine that “Carry On” could very well be an “anthem for the next new wave of country music.” For its part, the Wolf shot to number one in the Metroplex radio-ratings market last year in large measure because it reformatted itself as a “Texas country” station that played Pat Green songs several times a day.

“Pat’s appeal is not hard to understand,” said longtime Texas musician Ray Benson of Asleep at the Wheel. “Every generation needs its own fun-loving troubadour, and Pat’s this young, handsome guy with a lot of charisma, playing a real energetic music, teaching a new group of kids about the joy of acting Texan, about going on road trips and hanging out at roadhouses and drinking beer. We did those very types of songs ourselves in our time, and Pat is just updating them for kids today. To my eighteen-year-old son, Sam, my own songs about road trips don’t mean shit. But he does listen to Pat Green.”

Yet Benson admitted that he too is surprised at the number of young people who want to identify with this kind of music at this point in time. No less of an authority than Jerry Jeff Walker, who came to Texas in the late sixties from New York and helped set off the famed Austin-based redneck rock-progressive country movement with Nelson, Waylon Jennings, Ray Wylie Hubbard, and others, is convinced that a new movement has taken root, one that includes Walker’s own twenty-year-old son, Django, who wrote one of Green’s hits, “Texas on My Mind,” and who has just released an album of his own, Down the Road. There are now dozens of young Texas-based country musicians, almost all of them under the age of thirty, singing songs about Panhandle sunsets, Highway 281, Del Rio, San Antonio (which they all pronounce “San Antone”), honky-tonk romances, Shiner Bock, hangovers, pearl-snap shirts, Texas-bound trains, and lonely cowboys. The musicians unrepentantly give their songs Texas-y titles—“Dance by the Rio Grande,” “Texas Time Travelin’,” “100% Texan,” “Somewhere Down in Texas,” “Hill Country Here I Come”—and they declare in almost all of their interviews that they care nothing about becoming Nashville stars because they prefer the rawer, unpolished sound of their Texas country music. Many of them go so far as to shout out “Nashville sucks!” between songs at their concerts.

It is hard to imagine that this new group of young musicians—the more notable names include Cory Morrow, Roger Creager, Jason Boland, Kevin Fowler, and Rodney Hayden—will come close to the mythical status of the Texas musicians who were part of the original redneck-rock movement. At the very least, they will never be as bacchanalian. “Kids like Pat and Django are very responsible and work hard and don’t care about causing a lot of insurrection on the stage,” said Jerry Jeff, who thirty years ago was renowned for drunkenly performing songs like “Up Against the Wall, Redneck Mother.” Nevertheless, the new breed’s music is selling. Southwest Wholesale, which distributes albums to major retailers like Sound Warehouse and Hastings Records, saw the sales of what it calls Texas music jump from $900,000 in 2000 to $3.2 million in 2001. “That’s almost all from these younger groups that normal country audiences have never heard of,” said Frank Jackson, Southwest Wholesale’s senior project manager. “Already this year, sales in this category are up more than twelve percent, and you’re seeing more and more record stores creating ‘Texas Music’ sections to showcase these albums.”

Why is it that kids who were born after the heyday of Nelson and Jennings—kids who have spent their lives immersed in boy bands, hip hop, alternative rock, and Britney Spears—suddenly find themselves identifying with a guy singing some song about Texas? “Maybe the answer is real simple,” said Green. “Maybe they’re finally figuring out that it’s a hell of a lot more fun to be Texan than it is to be anything else.”

Pat Green spent his childhood on a small horse farm just north of Waco with his mother and stepfather (his parents divorced when he was seven), but he wasn’t an old-fashioned country boy. For a show in elementary school, he performed a break-dancing routine. He liked pop and rock music, and he attended a Sheena Easton concert on the campus of Baylor University. When he was fourteen years old, he did start listening to a local country music station, in part to hear the voice of a female disc jockey whose picture he had seen in Playboy.

At the tiny private high school in Waco that he attended, Green was the basic class cutup, always affable and always willing to stay out late on Friday nights. After graduating eleventh in a class of thirteen students, he headed off to Texas Tech University, where he joined a fraternity and changed majors every few months—moving from architecture to psychology to family studies to engineering to physics to range and wildlife management to, finally, general studies. He was known among his friends for his ability to “shotgun” a beer. He started learning chords on a guitar, but it was only so that he could strum along to songs like “Shine, Jesus, Shine,” at the Christian youth camps he worked at during the summer.

Then he went to a concert featuring Robert Earl Keen, the Texas singer-songwriter who then had a sizable college following because of such tunes as “The Road Goes on Forever.” “I wanted to do that too,” Green told me. “I wanted to get onstage and have a good time and sing about all the stuff that was going on in my life.”

Green is the first to admit that he didn’t know that much “stuff.” He had experienced no anguished romance, no angst and gloom, no dark nights of the soul. “The thing about Pat is he didn’t really have negative thoughts at all,” said his wife, Kori, who met Pat at Tech. (On their first date, he showed her a photo album of his family and his dogs.) “And he didn’t have an internal audit button like the rest of us that tells us that what we’re doing is a little nerdy or ridiculous. So when it came to being a musician, it never occurred to him that someone might laugh at him when he got onstage.”

He began practicing his guitar every day in the laundry room of his dorm—he learned “Blackbird,” by the Beatles, and half of Lynyrd Skynyrd’s “Sweet Home Alabama”—and he wrote his first song on the back of a report card. It was the tune about pouring Lone Star beer into his cereal and dipping Copenhagen. One day he drove more than three hundred miles with some friends to see Kris Kristofferson perform at Gruene Hall, then turned around and drove back to Lubbock that night. He became friends with another Tech student and fledgling country singer, Cory Morrow. In 1994 the pair staged their first concert, performing in front of a bunch of their roaring-drunk fraternity buddies at a local bar called Bash Riprocks. “Our number one concern was that we not drop our guitars out of nervousness,” Green said.

After Morrow quit school and moved to Austin to pursue his career, Green remained in Lubbock and began to build a following. “At first his audience was mostly guys who liked to drink while Pat sang,” said Kori. “Later on girls started showing up to meet the guys, and the audiences went from one hundred to two hundred.”

No one was yet predicting that Green had a future in the music business. In 1995, when he was 23 years old (he still hadn’t graduated from college), Green borrowed $12,000 from his family and friends and made his first album, Dancehall Dreamer, which included songs titled “I Like Texas” and “Southbound 35.” Two years later he released a second album, George’s Bar. By then he was back in Waco after finally graduating, working for his stepfather’s wholesale gasoline business and playing nightclubs and college parties on weekends. “What began to happen was that the Tech students would buy his albums, and then they’d take the albums back home wherever they lived in Texas, and their little brothers and sisters were soon listening to Pat,” said Kori. “Pat’s name weirdly began to get around. And soon it became this kind of in thing for college kids and high school kids to say they knew about Pat Green.”

Word spread fast. By 1998 small bars in college towns around Texas were booking Green. That year he also played an early show at Willie Nelson’s July 4 picnic and got his first booking at Billy Bob’s, where nearly two thousand people showed up to see him. Two of Billy Bob’s owners, Billy and Pam Minick, were so taken with Green that they quickly signed him to record a live album. “I hadn’t seen that kind of excitement in a young audience since Garth Brooks started making his rise,” said Pam. “But what made me realize Pat was going to catch on was watching the way parents who were there reacted to his music. They loved it.”

Not everyone was impressed. The reviewers from the alternative-weekly magazines began slamming Green—Rob Patterson went so far as to equate his rabid audiences with the crowds at Nuremberg rallies—but that was probably to be expected. What was surprising was that some older Texas musicians got in on the act. Robert Earl Keen told Patterson that he felt ambivalent about having inspired Green and the new group of singers like him. Charlie Robison, the popular 37-year-old country singer from Bandera (and husband of Dixie Chick banjoist Emily Robison) bluntly told the Austin Chronicle that Green’s music was not for “educated people or real music fans.” On his Web site, charlierobison.com, Robison also went after the entire new breed of Texas musicians. “I have problems with the current endless crop of people who pick up a guitar and a week later have twenty songs about Texas, Texas, Texas, beer, beer, beer, tacos, tacos, Guadalupe, Gruene Hall, UT, UT, A&M, A&M, etc.,” he wrote. “This is whoring a music I hold dear. If you ranch this land, grew up ranching it, and your family fought for its independence, as my family and I have done for 150 years, then you too would be insulted by people who take advantage of the Texas name and flag for financial gain.”

Robison recently told me he now regrets having made the comment about Green. “I’m sure some sort of jealousy was involved on my part about his popularity,” he explained. “I had been slaving for twelve years to write music about the Texas I knew, a Texas where people, including me, often felt like outsiders. But you have to give Pat credit. He was able to plug into this whole other audience out there ready to identify with his vision of what Texas is.”

Green was such an unabashed fan of Texas that one music critic wondered if he wasn’t “just some kind of satirist having us all on.” But it was real. He was just like the characters in his songs, always finding happiness either in an old pickup or in a dance hall with sawdust floors or in the music of legendary Texas singers like Nelson (whom Green persuaded to sing a duet with him on one of his albums). The first time he played Gruene Hall, he wept. When he married Kori, the ceremony was held in Luckenbach. At his concerts he sold a T-shirt that listed his name and everything he liked about Texas, including the Broken Spoke bar in Austin, the King Ranch in South Texas, mesquite trees, barbecue, bluebonnets, windmills, shotguns, fiddles, off-roading, and boots—a literal checklist of Texas icons.

In 2000 Green grossed more than $1 million in income from album sales, concerts, and merchandise sales. Yet because he was still ignored by the mainstream press, most older Texans had no idea who he was. Nor was he respected among the country music establishment, because he refused to sign a deal with a major Nashville record label. He didn’t need to. He was making up to $8 on every one of his self-produced albums that he sold. The Nashville labels were offering him only a standard contract, in which they would receive almost all of his album’s proceeds. “I was going to lose money if I signed with Nashville,” he said.

It wasn’t until the summer of 2001 that he signed a major-label deal. Republic Records, which happened to be based in New York, agreed to give Green more money up front (specific terms have not been disclosed). He also signed on with the William Morris Agency to get national bookings, and he found a hotshot Nashville publicist to get him media attention. He is now booked to appear on the Late Show With David Letterman in July, he has received some favorable reviews in national magazines (“Ten-gallon hats off,” declared People), and even several Texas music critics have had to declare that his music is improving. And they can’t say his lyrics are too Texified. His newest single, “Three Days,” a love song written for Kori, has no reference to Texas at all. “It makes me cry almost every time I hear it,” said my stepdaughter, Hailey. “He defines for me what true love is all about.”

The jury is still out on Green’s future, of course. “Thirty years ago, who could have imagined that some guy named Waylon Jennings was going to knock Barbara Mandrell out of her number one slot?” said Country Music Television’s Brian Philips. “We’re due for a new movement to sweep through and turn everything upside down again. This time, that movement might very well be led by Pat Green.”

Then again, it might not—which Green told me was just fine with him. “If I spend the rest of my life playing Texas dance halls, that’s fine with me,” he said. And despite his national bookings, Green was adamant about continuing to play the smaller honky-tonks around Texas whenever he got the chance. “That’s where I will always feel most comfortable,” he said.

That’s an understatement. Not long ago I took Hailey and her boyfriend, Casey, up to see him play in front of nearly four hundred fans at a hole-in-the-wall country bar called the Groovy Mule in Denton. Afterward we went back to Green’s bus, where he put the sweat-stained baseball cap that he had worn during the performance on Hailey’s head.

“Oh, my God,” I thought, “Hailey’s going to cry.”

“Oh, my God,” Hailey said, “I’m going to cry.”

“Hey, it’s not like I’m the Beatles or anything,” Green said.

“Well,” said Hailey, a tear trickling down her cheek, “maybe you are to me.”

- More About:

- Music