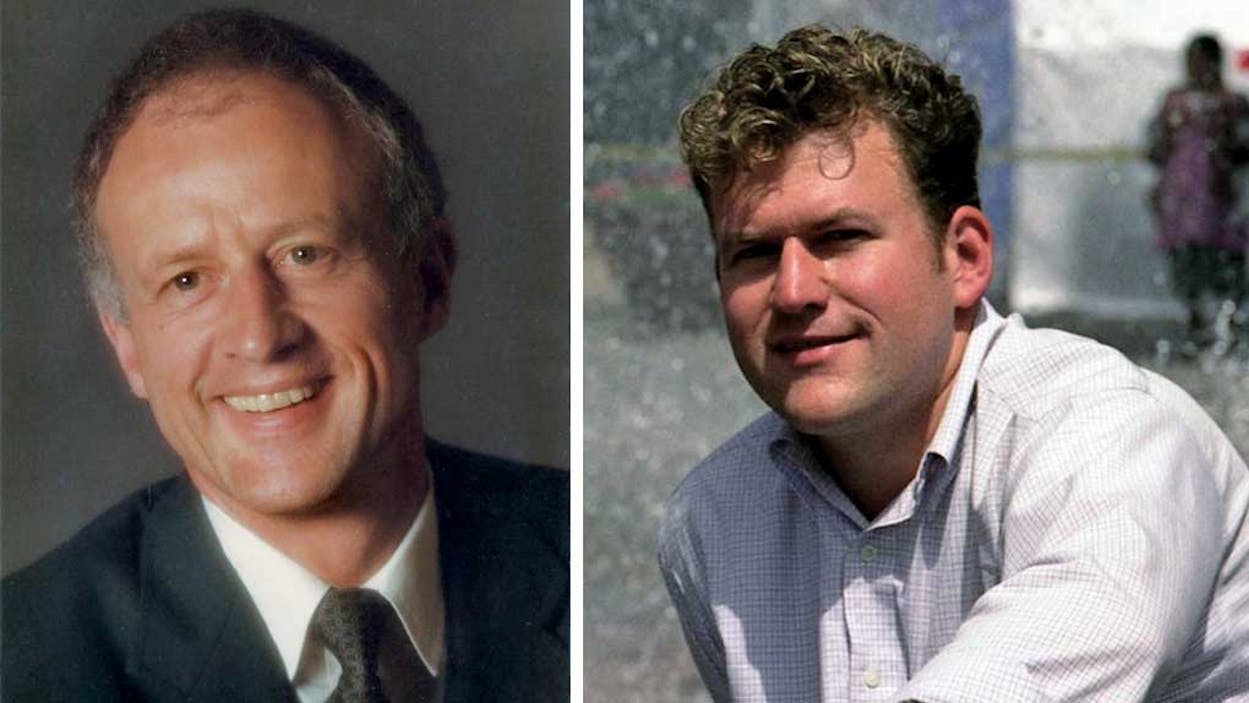

Stephen Lich was a college student when his father, Glen Ernst Lich, 48, was murdered in October 1997 by Ramiro Hernandez Llanas, a 28-year-old Mexican laborer. The crime took place at the family’s home, near Kerrville. In 2000 Hernandez was found guilty and sentenced to death. When, early this year, the convict was given an execution date, Lich, now a professor of economics at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, chose to attend. But the decision filled him with anxiety and dread—as well as curiosity. What would it be like to witness the death of the man who slew his father? What follows, in Lich’s own words, is an account of how he came to terms with his decision—and what he saw on April 9, when Hernandez was put to death.

Warning: The following contains profanity and descriptions of graphic violence.

I’ll never, ever, ever forget October 15, 1997. In my memory, it’s as vivid as anything I did earlier today. I was living in an apartment in College Station, and the phone rang at about three in the morning. Kerr County sheriff Frances Kaiser identified herself. She put my mother on the phone. My mother was sobbing hysterically. “Daddy’s been killed. We think he’s dead.” My first thought: What kind of accident were my parents in that killed him but she survived? Then Sheriff Kaiser took the phone back, and she told me the general details. My mother was robbed and attacked. They assumed the body behind the house was my father, but it had been beaten so badly the face was not recognizable.

A suspect had been caught, and his name was Ramiro Hernandez Llanas. Back in August my father had hired a carpenter to work on the house, and Hernandez was his assistant. I never met either of them because I had already gone back to school. But apparently there were some problems with the carpentry job, and in September my father fired the carpenter—quite angrily. Of course, Hernandez was out of a job then too. He showed up at my parents’ house a couple of weeks later, in early October, and said he was looking for work. My father said that he couldn’t hire him because of his illegal status, but he could at least offer him a place to stay and food, in exchange for help with some odd jobs. My father didn’t hold any grudge against Hernandez for the carpentry mistakes; in fact, he praised Hernandez for his strength (he was a big guy) and gave him the nickname El Toro. Hernandez slept in a barn, where the tools were kept.

On the night of October 14, he lured my father outside, claiming there was a problem with the generator. Hernandez beat him to death with a heavy metal bar that’s usually used for cracking rocks—bashed in his skull like a pumpkin. Then he went inside the house, took jewelry and money and raped my mother at knifepoint. I’m certain that he intended to kill her too. But through some miracle—which we’ll never explain—he fell asleep just long enough for my mother to break free.

It was horrible. The sheriff’s office arranged for a cleaning crew on the morning after my father was killed. Even so, spots of blood were still on the rocks outside the shed. Blood and gray gunk and flakes of bone were stuck between the floorboards. After his funeral, I spent the afternoon trying to scrub it out. It was my twenty-first birthday.

My father was an impressive and ambitious person. He was born and raised in the Hill Country and wound up having dual careers—one as an academic and another in military and government service. In his academic career, he went from being an assistant professor at Schreiner College, where he was the authority on the German Texans of the Hill Country, to holding a distinguished professorship in German Canadian studies at the University of Winnipeg.

He volunteered for the U.S. Army in 1972 and started as a buck private and a specialist in Eastern European languages. During summer breaks from teaching he worked as an army reservist and rose to the rank of colonel. He served as a military attaché and later as a diplomat. His team established a partnership with the Romanian military shortly after the Ceausescu government fell—a partnership that led directly to Romania’s membership in NATO.

My father was always proud to be a Texan, no matter where he was working. He once wrote a piece called “Texas Pissing” in his travel journal, about how, whenever he’d travel abroad, he’d go outside and urinate on the ground, marking his territory with a map of Texas. It represents the image he liked to portray: crass, yet intellectual; a Texas country boy at heart, while serving as a diplomat in Eastern Europe.

In 1993 he quit the academic life and retired to a mountaintop between Kerrville and Medina with a stunning view of the Hill Country. My brother and I helped my parents build a home there, one room at a time. We built a hydraulic ram to bring water up from a creek; we built a septic system. My father wouldn’t let the electric company spoil his view by putting power lines up his hill, so he and my mother lived without electricity, except for a generator that they ran for a few hours each day to charge some batteries, print papers, and send or receive faxes. He kept busy doing some work for the government, and he did consulting under the name Hill Country Institute.

He was hard on people. He was determined and demanding. His expectations were very high, especially for my brother and me. I don’t think he understood adolescents; he expected us to be intellectually mature from birth. He never understood why someone would want to read Stephen King books instead of classic or modern literature.

Though the two of us butted heads over the years, in the summer of 1997, when I was a senior studying economics at Texas A&M, he and I finally began seeing eye to eye. We were starting to understand each other. I had reached a point where I understood economics better than he did, and we could have discussions where I explained how to think about economic problems. I did research for him on portions of his job that related to business, finance, or economics. The last conversation we had was on the telephone a few nights before he was killed. At the end of it, I expressed gratitude for the guidance he’d given me. Those were our parting words.

Before the crime, I was against capital punishment. It was part of the party platform I adopted as an educated, moral person with liberal tendencies. But about a week after my father’s death, Kerr County district attorney Bruce Curry called and asked my input as to whether he should pursue the death penalty. I had just heard that Hernandez had sworn from jail that he was going to come back and kill my mother and grandmother, who lived at my parents’ home. While I stayed with my mother during the next few weeks, I slept with a shotgun under my bed, prepared to kill him myself if necessary. At that time, I had absolutely no doubt whatsoever about what the State should do. I told the district attorney that I supported pursuing the death penalty.

If ever there was a person who deserved to be executed, it was Hernandez. It turned out he had escaped from prison in Mexico while incarcerated for a previous brutal murder. Earlier in the fall of 1997 he raped a local teenage girl. Then he killed my father and raped my mother. Then he threatened he would escape again and kill my mother—and while in jail he threatened to kill a jailer with a homemade shank. If ever there had been a person who should be eliminated from the earth, it was Hernandez.

The trial took place in 2000, but I didn’t go. I didn’t really need to hear people recite the details. I had no interest in listening to my mother repeat her horrible ordeal or hearing the sheriff and deputy go through the evidence piece by piece. By the way, nobody ever questioned the evidence—there was no question of whether or not Hernandez did what he was accused of doing. When he got the death penalty, it felt like a battle had been won.

Afterward, I got on with my life. Looking back, I realize that I followed my father’s footsteps. He had done his graduate studies at the University of Texas at Austin, so I figured I might as well try the same. (My department—economics—was housed in the building adjacent to the one where he had studied.) He lived and taught abroad, so I tried the same. It suited me too. He was proud to be a crass, intellectual Texan. I was the same. And he had a particular style of mentoring students. They respected and admired him so much. I consciously try to emulate his teaching style.

One thing I wish to hell that I had had: advice. A young man needs this from his father. Advice on his career, advice on how to be a parent, advice on how to be a man. And I never got that. I’d go to his grave—he’s buried in a family cemetery outside Comfort—and talk to him about what was going on and what I needed advice on. Of course, I didn’t get anything back. He never said that he was proud of me when the top economics department in the country was going to interview me for a job. I couldn’t get his wisdom on choosing between positions at different universities. It was a one-sided discussion when I asked him about work-family balance.

But as I said, I was living my life. In 2004 I married a woman named Kristen Hassmiller, and two years later I started teaching at UNC. Kristen and I have three children; the oldest is named in honor of my father. And all through this time Hernandez was going through the appeals process. That was an emotional roller coaster: a long period of inaction, a new appeal resulting in more anxiety, waiting and waiting for the resolution, a sigh of relief when it was over, followed by another long period of inaction. I resented the teams who championed Hernandez’s case. Did they think about what would happen if they got the conviction overturned and Hernandez was released while he awaited a new trial? What if this two-time murderer were allowed to walk the streets? When they argued that he posed no further threat to society, would they have welcomed him to stay at their homes?

The defense attorneys dug up and paraded every detail of Hernandez’s past—but they weren’t completely honest about it all. I know that it’s their jobs to make every possible claim they can, no matter how ludicrous, in order to win. But once a claim is determined to be false, it should be buried. For example, the claim that Hernandez was retarded [the Supreme Court ruled in the 2002 Atkins decision that states could not execute the mentally retarded]. I understand, and share, sympathy for defendants who are “intellectually disabled.” But Hernandez was not retarded by any stretch of the imagination. Look at his cunning escape from the Mexican prison before he killed my father. Look at his behavior and the planning that went into my father’s murder. Look at the evaluations of other psychologists. Only the defense attorneys’ hired guns claimed he was mentally incapable. A panel of judges determined the claim to be meritless. That should be the end of the discussion. So many people believe it to be true, simply because his lawyers wanted to see if an Atkins claim would go anywhere.

I watched the news closely. There was more coverage in the Mexican news than the U.S. They portrayed him as a young man who simply went to work in Texas to earn money to send home to his elderly mother; then he became the victim of a cruel criminal justice system. I read a news article with quotes from his mother, and I found a video of a television interview with her. I wanted to know exactly what she said, so I hired a student to transcribe it. I found it interesting that she contradicted the allegations of retardation. What was his mental illness, she was asked. He sometimes fainted. Was it serious enough to get treatment? No. The interview showed his house—not the slum that witnesses at an evidentiary hearing had talked about. I went to Google Maps to look at his neighborhood and saw the “dump” where these witnesses said his family lived. It looked like a typical salvage yard. The news stories sought sympathy based on his upbringing and his claimed intellectual disability, but did the reporters do any research?

Before his lawyers brought up his supposed mental disability, there was also the affair with consular rights and Mexicans on death row—that he wasn’t advised of his consular rights when he was arrested. This went to the International Court of Justice. That was a big deal, and I wondered how it was going to play out. I felt relief when it was over, with no consequences for the case. More recently, there was concern about the execution drugs, but then Texas found another supplier of pentobarbital—just in time before the execution.

Over the past few years, I would occasionally check on the status of the case. In December, I did an Internet search and saw an article in the Kerrville Daily Times that there was, finally, an execution date: April 9, 2014. I searched further back, and I found an article with the words “exhausted all appeals.” It would be over soon. No more emotional roller coaster. We could wrap up this long, painful affair. I had never understood what people meant by “closure.” But maybe there would be a feeling of relief at the end of this long, painful chapter.

On January 9, I got an email from the Victims Services Division of the Texas Department of Criminal Justice setting the wheels in motion for me to be a witness to the execution. And instantly, reflexively, I knew I would want to be there, in Huntsville. Then they sent a formal letter with a packet of information about witnessing the execution. It explained which family members were eligible to attend. It said that we could bring “support” people with us, to accompany us but not watch the execution. They would wait in an adjacent room during the actual execution. It talked about the logistics of the execution. It had some advice on interacting with the news media. (I suspect that almost all victims’ families have had bad interactions with the media.) As a witness, I underwent a background check. They also offered to arrange travel plans, to find a spiritual or emotional counselor, to reimburse me for any costs. I declined. My only requests were to receive notification about media interest and the status of any appeals.

My mother and sister decided not to go, but I wanted to watch the execution. Why? What did I hope to get out of it? I asked myself this question a lot. I didn’t really know. I second-guessed my decision to attend—a lot. I knew I would be watching a person put to death against his will, a potentially gruesome event. At first, I envisioned that he would just fall asleep. Then I realized that he might struggle or strain. My initial vision had him calmly accepting his fate. But likely, he could be freaking out as they executed him. Or maybe it could be the other extreme. The killer would enter the room complacently, the IV would be administered, and the fluids would flow. An uneventful minute later, it would be finished. Would that leave me unfulfilled?

I have seen someone die before. Two years before my father’s death, a loved one died in my arms after ingesting cyanide. I had tried to stop the suicide attempt. The last moments were horrible; the final words, about the physical sensation, still haunt me. Maybe I didn’t want to watch another death. So I kept wondering whether it was a good idea to attend.

I asked myself, How would I feel if he simply passed away in his prison cell one day? I thought, well, I’d be okay with that. But would it be more reassuring if I saw it myself? I thought so. Another question I asked: Was it important to have retribution? Hypothetically, would I get more satisfaction if they tortured him to death? No. I was certain of that. Splatter his brains, just for the hell of it, because he did that to my father? Definitely not. I was not comfortable with that.

I asked myself, If I were to meet Hernandez face-to-face, what would I say or do? And I thought, I would say “fuck you.” Fuck you for hurting my family; fuck you for making it so hard for people to relate; fuck you for depriving my children of their grandfather; fuck you for depriving me of the guidance I’ve needed as I’ve grown up. Fuck you for everything. Then I realized that there was no bigger insult to Hernandez, no bigger way for the world to say “fuck you” to him, than by condemning him to death.

The reaction that I heard the most from others before the execution: “I can’t imagine what you’re going through.” No, I thought, you can’t. I couldn’t imagine what I would be going through either. I had so many thoughts and questions, and there was no guide, nobody who had written about their experience as a family member witnessing an execution.

Despite moments of clarity, I had just as many moments of doubt and confusion about the whole issue of capital punishment. One thing I was certain about, even before the execution, was that people are naive when they say that they are absolutely opposed to executions or absolutely for them. Nothing can be black or white. I could debate this for hours, though in truth, I won’t discuss capital punishment with others—and I have almost never discussed the murder with others.

But I debated my feelings with myself. And I did understand why I wanted the execution. I felt I would have peace of mind when Hernandez was gone and this ordeal was finished. My father’s death has dragged on for sixteen and a half years. Time doesn’t heal all wounds. I pick at scabs, and sometimes they fester. I haven’t let go of my father’s death. I don’t want to. If I let go of it, then I let go of a piece of him. If I make his death less important, then I make his life less important too.

***

The week before the execution was filled with a flurry of appeals and petitions, mainly about Texas’s new supply of pentobarbital, the execution drug. Lawyers for Hernandez and another murderer, Tommy Lynn Sells, argued that the TDCJ needed to reveal the source of the execution drugs to confirm their quality so they wouldn’t cause a cruel death. Their executions were stayed by a federal judge—but then the stay was overturned. On April 3 Sells was executed. Sells’s failed appeals guaranteed that Hernandez would be executed too.

On the evening of April 7 Kristen and I got in the car and began the trip to the execution. It’s a long drive from North Carolina to Texas. I was tired during the drive—I hadn’t slept well in weeks—but determined to make it to Huntsville in time. On the way I thought a lot about my father. He loved to drive—that’s another thing I got from him. I wondered what he would be doing if he were still alive. I thought about my kids and realized the thing that I regret the most about his murder: I wish my dad had known his grandkids. Having grandkids would have been important to him. He deserved to know them—and they deserved to know him.

I also thought about how well my father treated Hernandez. He let him stay at his place, made sure he had food, bought him tequila and beer. And this person turned around and took advantage of that so brutally. My father had always been a curious man, and I had inherited that curiosity. I wanted to know what it would be like to watch Hernandez die. Now I was going to find out.

When we got to Huntsville we checked in at the prison’s administrative offices and met two women with the TDCJ’s Victim Services Division. Anyone who thinks the TDCJ in Huntsville is a bunch of merciless people needs to meet the two women who were assigned to us. They were wonderful and compassionate. They showed us a video of what the prison looked like, what the execution chamber looked like. They told us all about the wide range of experiences they had seen. They were very good at explaining what to expect. The worst thing that had happened to a family member, they said, was that someone had fainted. They drove us over to the Walls Unit, warned us where the media would be hiding, where the protesters would be.

The prison building is old. It looks like a castle, with guards walking along the parapets. In the center, there is a courtyard. In a corner of the courtyard, looking very much like a garden shed, is the Death House. We were led into the prison and taken into the first room, where they patted us down for electronic devices or weapons, then we were taken to a second room, where we waited for about ten minutes. The phone rang at about six minutes before 6 p.m., and it was time. I felt a deep sense of dread as we walked down this long corridor and into a room looking into the actual execution chamber, which was smaller than I’d imagined, like a doctor’s examining room, but even smaller.

And there he was. I’d never seen Hernandez in person before, and he was a huge and hideous man, lying on the execution table. A sheet covered him from his feet to his chest, and an enormous, thick leather belt strapped his chest to the table. His arms were stretched out to the sides like—I hate to use this comparison—he was about to be crucified. IV tubes ran to his hands, which were wrapped tightly with Ace bandages. The bandages weren’t for any medical purpose; rather, they were to prevent him from making obscene gestures.

I stood right at the window, and he was only two or three feet away. He looked like Marlon Brando in the climactic scene of Apocalypse Now, but even more heavyset. Looking back on it, I could use that scene as a description of how it felt—the tension as Captain Willard walked into Kurtz’s tent, to hack him to death while he lay helpless. I felt extremely angry, like I was stepping up to someone to start a fight, confronting someone who had really hit hard at my family and now we were hitting back at him. He was strapped down, helpless, defeated, staring at the ceiling, blinking rapidly, licking his lips, biting his upper lip. He seemed nervous, but he wasn’t angry or freaking out.

Our witness room was the size and shape of a walk-in closet. Two people could stand abreast, and we could stand four rows deep. I could hear muffled talking on the other side of the wall and knew that’s where his family was. Every part of the day had been choreographed so that Hernandez’s family and I never came into contact with each other, but now I could see them in the reflection of a mirrored window on the opposite side of the room. A large middle-aged man and a large middle-aged woman stood at the front. I believe they were his brother and sister. I was told that behind the mirrored window were a team of guards and the medical staff who administered the drugs. (“Medical staff?” I thought. “Wouldn’t it be more accurate to describe them as executioners?”)

After everyone was inside the execution room and the door was locked, Warden Jones—a small man, dressed in a fine suit, with a soft voice—asked Hernandez if he wanted to make a final statement. He said, “Yes, sir,” and he began his statement in Spanish. He talked about how he loved his family, was sorry for what he’d done to them. He looked at them as he talked and blew them kisses. He went into a kind of public service announcement, telling kids to listen to their parents and do right. Then he turned and looked at me and said, “And to the family of my boss, I want you all to pardon me, I want to let you know I love you.” He didn’t say “my victims”; he said mi patrón, “my boss.” And at this point he started making these big smacking kissing noises. It was grotesque.

Then he went through the whole statement again, again turning toward the witness rooms and making these giant smacking sounds with his lips, blowing kisses at us in the witness room. That was gross, and it made me furious when he did it a second time. So this time when he turned to us, I flipped him off. I hope he saw it, and I hope he recognized me as the son of his . . . boss? No, his victims.

Then he did the whole statement a third time. And when he again turned to us, I told him “fuck you” with my middle finger. All of that talking and talking was a performance. He was an eloquent, well-spoken man, especially for one who was “intellectually disabled.” He kept talking. Maybe he was trying to buy a few extra minutes. Apparently the warden had enough and gave the signal to start the drugs. The very last sentence—and the first time that he deviated from his rambling about loving everyone—was something like “De verdad, estoy viendo a la luz y al ángel de Dios”: “I can honestly see light and the angel of God.” Then he made a quick grunt and a snort and stopped breathing. You could see the moment when his body just switched off. It wasn’t gruesome, but it was clear when it happened. A few spit bubbles started forming on his lips as the last of the air came out of his lungs, and a line of drool ran down his cheek.

We stood there in silence for another eight minutes or so, kind of awkwardly. No one said anything; we just watched him. Finally, a doctor came in to check his vital signs and pronounced him dead. The warden noted the time of death: 6:28. A guard unlocked the door of the witness room, and everyone walked out without talking, back through the courtyard, into the prison building. That was it.

How did I feel? I had gone into the room, confronted the horrible thing that had brought such badness into my life, and I walked out feeling that I had won. The confrontation was over, and he had lost. I hadn’t wanted him to die in agony. I just wanted it to be over. I’ve heard assault victims talk about feeling trapped by their fears of their assailants and feeling empowered when they take back their lives. Certainly that was true when I saw Hernandez die and when I walked out. It was done. It was good to be there, good to witness. Watching it made it very, very real; made the end very real. It didn’t traumatize me. It wasn’t overly unpleasant to watch him die. It was reassuring to have it right in front of me. I thought, “I’m satisfied with this. Done. The end.”

His final statement affected me more than I ever could have expected. I won’t ever know what to make of that last sentence, about seeing the angel of God, in the instant before he switched off. Three possible explanations: it was the way that he planned to end his statement, or it was a physical phenomenon when the brain shut down, or it was a spiritual phenomenon. I would rule out the first hypothesis—it was so different from everything else he said, and he must have been barely conscious at the time. That leaves the other two.

At one point, he said, “I am content. I am no longer carrying any guilt.” In my interpretation, that implies that he had known that he was a person who deserved to feel guilty for the horrible things he had done, and that he regretted who he used to be. He knew that he had wrecked the lives of everyone in that room. I thought, “Good, the execution forced you to come to terms with what you did.” If this forced him to realize and think through what he’d done and how he’d affected people and changed the world and done something horrible and he was being punished for that—that was satisfactory. I’ve since read the final statements of other executed killers, and I see the same statement in some of them. Maybe that’s an argument for capital punishment: the killer doesn’t have to confront his sins when incarcerated indefinitely. The killer doesn’t face that moment where he asks himself, “Can I make peace with myself?” He wanted to believe that he regretted being a monster. (Did he truly feel it in his heart? I don’t know.) He was trying to be at peace with who he was. Would this have happened if he had never been incarcerated? No. Would he have been forced to come to this understanding if he had been given an indefinite sentence? I doubt it.

But don’t get me wrong. He didn’t redeem himself to me with that final statement.

Right now I feel two huge sources of relief. First, I don’t have to worry about him being out there anymore, about his conviction getting overturned and him walking the streets. I don’t think that the purpose of sentencing a person to death is punishment. Removing a threat, or a perceived threat, is the real goal. Putting down a rabid dog.

Second, the legal process is over. I’ve hated every moment of it, how protracted it was, how much of a game it was between lawyers on each side. I don’t think anyone was looking for truth or justice—everyone was looking to score a victory. They just wanted to win. From the start the DA was so pleased to get this case happening in Kerr County, he was so enthusiastic about prosecuting it; he was going to score some points with the citizens of Kerr County who elected him. Then the appellate attorneys were trying to score points—overturning a death sentence would have been a huge win. But they weren’t interested in truth. If they had gotten a psychological examination that showed that Hernandez was intellectually capable, they wouldn’t have accepted that truth; they would have just purchased a different psychologist, one who would support their position. Though quite clearly, the prosecution did that too—they hired Dr. James Grigson, a psychiatrist who was likely to find Hernandez a continuous threat to society—Grigson, who testified that almost every single one of 167 defendants was a sociopath.

This whole experience has made me think a lot about capital punishment. I would encourage people to think about executions on a case-by-case basis, not in terms of being “for” or “against” the principle of the death penalty. I am not “for” the death penalty any more than I am “for” abortion. Neither is a decision that can be taken lightly, and neither is a pleasant outcome. But there may be circumstances where each is appropriate. When there’s a murder, a person should ask: Was this crime particularly brutal, above and beyond a simple murder (if there is such a thing)? Was the evidence undeniable? And, importantly, does the person continue to be a threat? Put all that together. In this case, I tell people all the things Hernandez did—the murder in Mexico, the rape of the teenager, the murder of my father and rape of my mother, the attack on the jailer—and I say, “Maybe you understand now why the jury sentenced him to death.” No one disputed what happened—there was no dubious eyewitness testimony or junk science. I think we’re right to be hesitant about using executions when we have doubts about innocence, when we have shady evidence. And if the person can still be rehabilitated, then that’s another thing to consider. That wasn’t the case here.

Would I recommend witnessing the execution of the murderer of a loved one? My biggest fear was that seeing another death would traumatize me in the same way that my father’s murder did—but no, lethal injection is not gruesome. It’s like watching a person being given anesthesia before surgery. It’s almost the cleanest way that a person could die. Families of victims will definitely be contrasting the way that the killer dies to the way that the loved one died.

Don’t expect vengeance or punishment. Don’t expect that it’ll cure your anger or sadness. But you will know that the killer is no longer a threat to your family or your emotional well-being. And it will give you an opportunity to confront your emotions and opponent, and you will win. When the murder happened, the killer took control of your world. The killer had the power to radically change your life. After the execution, the killer is powerless. You aren’t controlled anymore. Watching the execution drives the message home, drives the message into your heart and mind.

I hadn’t expected that the confrontational moment would be so helpful, when I stepped into the execution house and saw him there. I hated this man. I still do. And it’s human nature to want to avoid unpleasant confrontations. This was as unpleasant as it gets. And I also had to confront my inability to talk about the murder. I’ve always been terrified that people will see me as a freak when they know. Probably, they still will. I look at my own face in the mirror, and I can’t believe that it’s someone who deliberately chose to walk into the most notorious execution house in the nation in order to see someone die. I hope people don’t judge me harshly because of it. But the murder is so important in shaping who I am, so they really should know.

It was such a relief to get home after this trip. As soon as we drove up to the house, my kids came running out, and I jumped out and hugged them tightly. I missed them so badly. Usually I get miserably homesick when I stay at work past six or seven; this trip was only the fourth time in seven years that I’ve been away from the kids overnight. So lots of hugs and kisses when I got home. It wasn’t just about me missing them but also having spent five days thinking about how their grandfather was missing them. We went and checked to see how the chickens were doing, how the vegetable garden was doing. We looked at the thousands of flowers that had burst into bloom over the past week.

Whenever my father went on a trip, he always brought back some relic from the place he had been. It might be a wooden carving from Mexico, hand-knitted socks from Romania, or a unique rock from Arizona. I brought back a present for my kids too: illegal fireworks smuggled into North Carolina from a neighboring state. My father would definitely not have approved of such a frivolous thing. But his grandkids loved it and so did I. We celebrated him until the fireworks were gone.

As told to Michael Hall