“Stand straight. Keep your chin down. Relax. Quit worrying you’ll look like you’re a goober.”

For most of Natalie Maines’s life, her father, Lloyd, the potential goober, was her major influence. He was the one with the music career—the revered producer of records by everyone from Jerry Jeff Walker to Wayne Hancock, and a wicked-good steel guitar player to boot—and she obviously learned from him well, though his teachings were so low-key and subtle that she realizes today she learned most everything by osmosis. And it was he who facilitated the deal that landed her in the Dixie Chicks, her ticket to the big time. But in this East Austin photographer’s studio, before lights and cameras that are completely foreign to a behind-the-scenes player like Lloyd, she’s the one who calls the shots. She has even loaned him the makeup artist she had flown in from Nashville (standard operating procedure when you’re a chart-topping country star) and taken the time to give him a few tips on applying foundation. Natalie’s on a much-deserved break from the road right now, she has told me, turning down all requests for interviews and media ops. But since her dad is involved, she has made an exception. She’d do anything for him.

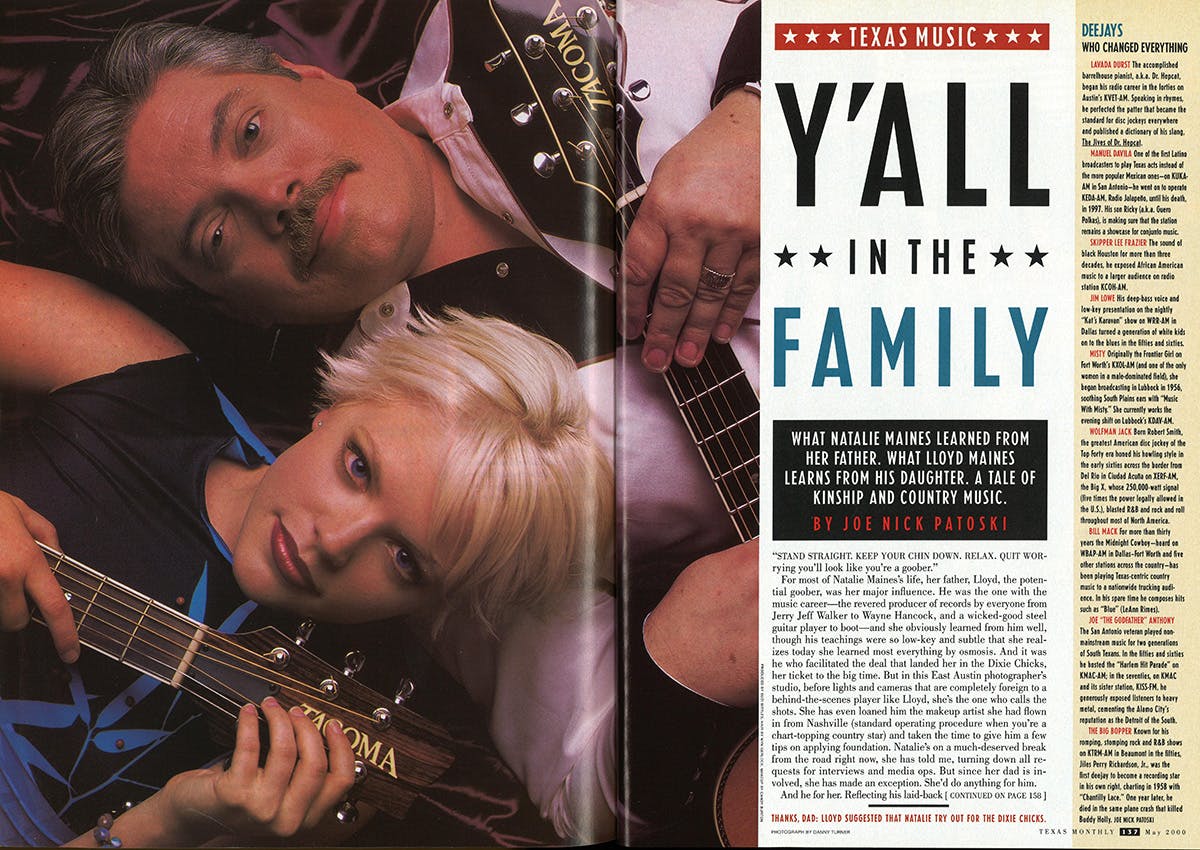

And he for her. Reflecting his laid-back approach to life, 48-year-old Lloyd patiently waits for his daughter to strike a pose before he straightens up and places his hands on her shoulders. His idea of mischief is to make devil’s horns with his fingers behind her head. For her part, 25-year-old Natalie—whose public image is that of a bubbly spitfire hardly able to contain her energy and always looking as if she’s about to burst into song—handles the session like a seasoned pro, cool, calm, and quiet, until she turns on the perky charisma and flashes a radiant smile in anticipation of the whirs and clicks.

Posing is business as usual for her. She’s used to having all eyes on her—in this case, makeup artists, publicists, photographers, and photographer’s assistants, who do what they do so she can do what she’s supposed to do. But with her mother, Tina, looking on, the superstar seems abnormally normal. For a few moments, she’s the sweet gal from Lubbock all over again, joshing with her daddy. He’s hugging her. She’s hugging a guitar. They’re the unsung first family of Texas music, playing themselves.

Lloyd has never been anything but normal. An exceptionally decent fellow, particularly for someone in his line of work, he’s as earthy today as he was 25 years ago, when he made his name as a member of the Joe Ely Band, a crack ensemble way too raucous for Nashville tastes but with too much High Plains red dirt in their boots to pass as rockers. His steel guitar was their secret weapon. He played it like it was a nitro-fueled dragster, which certainly went against the grain of how steels were supposed to sound in those days: all weepy and morose, as a counterpoint to the melody.

It was while he was working with Ely that Lloyd developed a side interest in producing. His first project, Terry Allen’s Lubbock (On Everything), was a rather auspicious debut. Recorded at Don Caldwell’s studio in 1977, the album still holds up as the most succinct commentary on the West Texas condition ever captured on audiotape. The session cemented Lloyd’s reputation as something of an efficiency expert too. The band he put together—featuring his brother Kenny on bass and a drummer named Curtis McBride—jumped in behind Allen and his leather briefcase full of songs to complete 22 tracks in two days. Lubbock (On Everything) also put on view Lloyd’s particular knack for bringing out the best in people. “Terry had recorded before for Capitol, and when he did, the producer gave him grief for stomping his foot as he sang,” he says. “Instead of trying to hide that, we kept it in. His foot became the kick drum.”

The work that followed was mostly of a more mundane variety, meaning whoever and whatever walked in the doors of Caldwell’s studio. There were aspiring country stars, of course, and rock and rollers, along with Christian contemporary and gospel groups, heavy metal bands, conjuntos and other Tex-Mexers, and local commercial clients that needed audio for radio and TV spots. He also took the lead in producing the eight albums recorded by the Maines Brothers Band, the country and country-pop combine that dominated the South Plains live music circuit after Ely moved to Austin in 1981.

Ely had wanted him to come along, but Lloyd decided to stay in Lubbock so that he and Tina could raise their two daughters, Kim and Natalie, where they themselves had come of age. He got off the road altogether following an extended international tour on which the Ely band opened for the English punk band the Clash. “My kids were old enough for me to realize that they needed a dad at home,” he says. “And I liked the idea of producing, of recording something that’s going to be around a long time for people to criticize and analyze, as opposed to playing live, which was for the moment. It didn’t matter what I produced. I just enjoyed the process, and it allowed me to pay the bills.”

Neither he nor Tina had made a big deal of what he did for a living. He had made flying all over the world with Ely and rubbing elbows with Linda Ronstadt seem like another day at the office. But it sure rubbed off. “I remember Terry and Joe and the Tornado Jams and Stubb’s,” Natalie says. “But I didn’t grasp how great they were. The person I really remember is Jo Harvey [Allen, Terry’s wife, an accomplished playwright and actress]. I adored her. I always wanted to hang out with her. I was sort of a little brat. And her term of endearment for me was ‘little shit,’ as in, ‘You know, you’re a real little shit.’ I loved it.”

No one remembers exactly when Natalie’s destiny became obvious. She hadn’t taken a single singing lesson, but she had quite a voice and an attitude to back it up. It might have been when the precocious three-year-old continued banging on the piano, willfully ignoring her dad’s demands that she stop even though she knew she was making him mad. Or a year later, when she tap-danced to Cecil Caldwell’s music and sang “How Much Is That Doggy in the Window?” backed by the Maines Brothers Band at the West Texas Opry.

“Dad was putting me onstage whenever I wanted,” she says. “I’d go to rehearsal and work up a song for the show with the band. He was just so proud.” Tina thinks it might have been the time Natalie’s second-grade teacher called her at home after Natalie refused to answer a particular math question “because I’m going to be a star.” Standing in line one day at the Baskin-Robbins, Tina became certain that her daughter was headed for some kind of career: “All of a sudden I heard ‘Greased Lightnin” being belted out behind me and I cringed. She knew every lyric and every line of dialogue from both Grease and West Side Story and could recite them in several different dialects. She had Madonna’s ‘Like a Virgin’ down cold.”

Lloyd was pragmatic about accommodating his little girl, but he wasn’t pushy. If he needed someone to sing backing vocals for a commercial, he knew Natalie would be only too happy to help. “One time he needed a vampire’s laugh for a spook house, and he let me do it,” she recalls. “The guy designing the spook house said I was excellent.” And whenever Natalie asked, Lloyd passed on the sort of deep knowledge that isn’t taught in school, like the value of doing your own songs and keeping your publishing rights, or how if someone called you “baby” in L.A., it was the same as someone in Nashville calling you “hoss.”

After graduating from Lubbock High School a year early, Natalie spent a semester at Canyon’s West Texas A&M University before transferring to South Plains College in Levelland, which was closer to home. There, her musical inclinations became her studies, and she began performing on her own more. With Lloyd backing her up on acoustic guitar and manning the console, she made a demo tape and earned a scholarship to the prestigious Berklee College of Music in Boston. Again, one semester far from home was enough. She moved back to Lubbock in 1995 and had enrolled at Texas Tech University when she got the call that changed her life.

Daddy had already given his blessing in advance. His production credits on albums by Jimmie Dale Gilmore (his self-titled second recording for the HighTone label), Butch Hancock (The Wind’s Dominion and Diamond Hill), and Jerry Jeff Walker (Navajo Rug) had raised his profile enough that he had great word-of-mouth within the community of Texas country players. It was this reputation that led to, among other things, a stint playing on two albums by a fringe-wearing girl group talented enough to play their own banjos, guitars, and fiddles. They called themselves the Dixie Chicks.

After Robin Lynn Macy and then Laura Lynch had left the Chicks, founding sisters Emily Erwin and Martie Seidel sought Lloyd’s advice for a replacement. He gave them a copy of the demo tape Natalie had made for Berklee. Could his daughter have the right stuff for them? He was apprehensive: She was only twenty—his baby girl. He knew the road was treacherous. But he also knew she was a go-getter who absorbed things fast.

Natalie accepted an invitation to try out with one caveat. “I won’t wear those cowgirl clothes,” she told Emily and Martie. A week later, she was performing onstage as the third Chick. The band’s sound and look changed dramatically. So did its financial outlook.

Especially after Lloyd brought a certain tune to the Chicks. He’d gotten a call from a woman in Amarillo named Susan Gibson, who asked if he’d be interested in producing a record by the band she played in, the Groobees. He sat down to listen to their audition tape and was floored by the first song, about a child leaving home. He played it nine times. “The dad even says, ‘Check your oil,’” Lloyd marvels. “I don’t know how many times I’ve said that.” After producing the Groobees, he persuaded the Chicks to cover the song, “Wide Open Spaces.” He says that when he sits in with the Chicks on the road, “you think you’re at a Beatles concert. These girls and these guys have tears in their eyes. It’s like an anthem.”

Having her father play with her band has made Natalie aware of how much they are in sync with each other. “We actually hear things the same way—what to hear, how a song is structured,” she says. “Some of it’s telepathic. He’ll just stop the tape and I’ll know what he’s going to say.” Sometimes she even knows what he’s supposed to say. “When we played ‘Cowboy Take Me Away’ on The Tonight Show, we all told him during rehearsal that he was doing one little lick different from what was on the record, and he’s the one playing on the recording. We had to teach him the lick again.”

The best trick that Lloyd picked up in the studio and passed on to Natalie has been how to use and not use reverb, the echo effect that was cultivated by Norman Petty in Clovis, New Mexico, and became Buddy Holly’s signature. “Norman had the most calming effect in the studio,” Lloyd says. “One thing he taught me was that when you’re overdubbing, it’s best not to let yourself hear reverb, because you’ll sound better than you really are. He said, ‘I like to hear a voice as dry as possible.’”

Natalie shares that opinion: “No reverb in the studio, on tape, in the headphones. Why use it if you don’t need it?”

What else did Dad teach her? Stick to your guns, a lesson all the Chicks have taken to heart. “Emily played banjo when she first went to Nashville,” Lloyd remembers, “and she was told she shouldn’t play banjo. She said, ‘Yes, I can, because that’s what I do.’ Guess what’s the hot studio instrument of the moment in Nashville?” Lloyd smiles wickedly. “Those three girls are nice and they’re sweet,” he continues, “but the people around them know they have to get the job done, because if someone on the team hasn’t been doing so, they’ll tell them, ‘You’re outta here’ in a heartbeat.”

Despite his daughter’s rapid rise to platinum-selling status, Lloyd has been resolute about staying in the trenches, focusing on producing up-and-comers like the Robison brothers, Pat Green, and his latest protégée, Terri Hendrix, who’s taking the do-it-yourself route, starting her own label and racking up sales of 10,000 units on her second album, Wilory Farm, and 6,000 on her follow-up, Terri Hendrix Live. He’s also taking the opportunity to work with old-timers he admires, most recently Johnny Bush and Hank Thompson. And he still sits in with Joe, Jerry Jeff, and Robert Earl Keen, but only as his time and interest allow. Robert Earl regularly sends him his touring schedule—just in case.

The biggest change in his life hasn’t been nurturing a Dixie Chick; it was finally leaving Lubbock. He spent so much time recording bands in Austin—219 days in one year by his calculation—that he and Tina relocated there in 1998, reasoning that the kids were out of the house and the work was where the work was. They miss their friends and family, Tina says, but they don’t miss other things. “I heard that it rained mud the other day,” she says. “That I don’t miss.”

Lloyd’s style of working remains the same. “I like to keep it moving,” he says. “I don’t like to waste time. Once you’ve got the machine rolling, it’s best to keep it there until you hit a wall, then you take a break. The reason I crank out so many records is that most of them are low-budget; we can’t spend a lot of days making it. An act might come in with $10,000 to do the whole master. That’s what major labels spend on catering!”

Natalie thinks he undersells himself. “I just did a session in Los Angeles with the Pretenders and Stevie Nicks,” she reports, “and they didn’t know who he is! And they should! He’s almost too fair. Not only does he tell you when it’s sharp or flat, he arranges songs. He ought to get a songwriting credit on every track he produces. He has never gotten credit for being as creative as he is.” Spoken like a doting, fiercely protective daughter.

“I’ve been a little scared of this business in some ways, just because it’s so volatile,” Lloyd explains. “Being self-employed, you wake up hoping the phone will ring. She dove right into it, head-on. I’ve observed her fearless approach. Maybe some of that has rubbed off on me.”

Just as his take on Texas music —that it’s okay to be imperfect as long as you put your soul into it—has rubbed off on the young pro at the top of her game. “Follow your heart, do what you want to do, and don’t do anything you don’t want to do; that’s what he taught me,” Natalie says. “There’s always give and take, but stick to your guns. We’re a band. Our passion is not to be stars, but to play music and reach our audience. “I didn’t realize until recently how naturally it all came to me,” she says, packing her bags when the shoot is over. She’ll spend the night at her parents’ house before hitting the road. “We both recognize we’ve got a good thing going on,” she says emphatically, leaving no room for more questions. “We know it.”