Protest season seems to be upon us after the recent election. Citizens are taking to the streets to show their displeasure with a new leader, which isn’t anything new in the United States. Before the original Brexit united us, we were anything but polite. Of course you remember the Boston Tea Party, and you might even have retained some knowledge of the Stamp Act, but what about Governor Tryon’s Barbecue? It sounds festive enough, but the most belligerent barbecue in history served as a chilly nineteenth-century welcome to another new leader.

William Tryon was a British soldier who brought his family to North Carolina in 1764. He had moved to the colony to become its governor, but Governor Arthur Dobbs was still in office. Tryon took the position of lieutenant governor and waited his turn, and when Dobbs died in March 1765, Tryon happily stepped into the vacated seat.

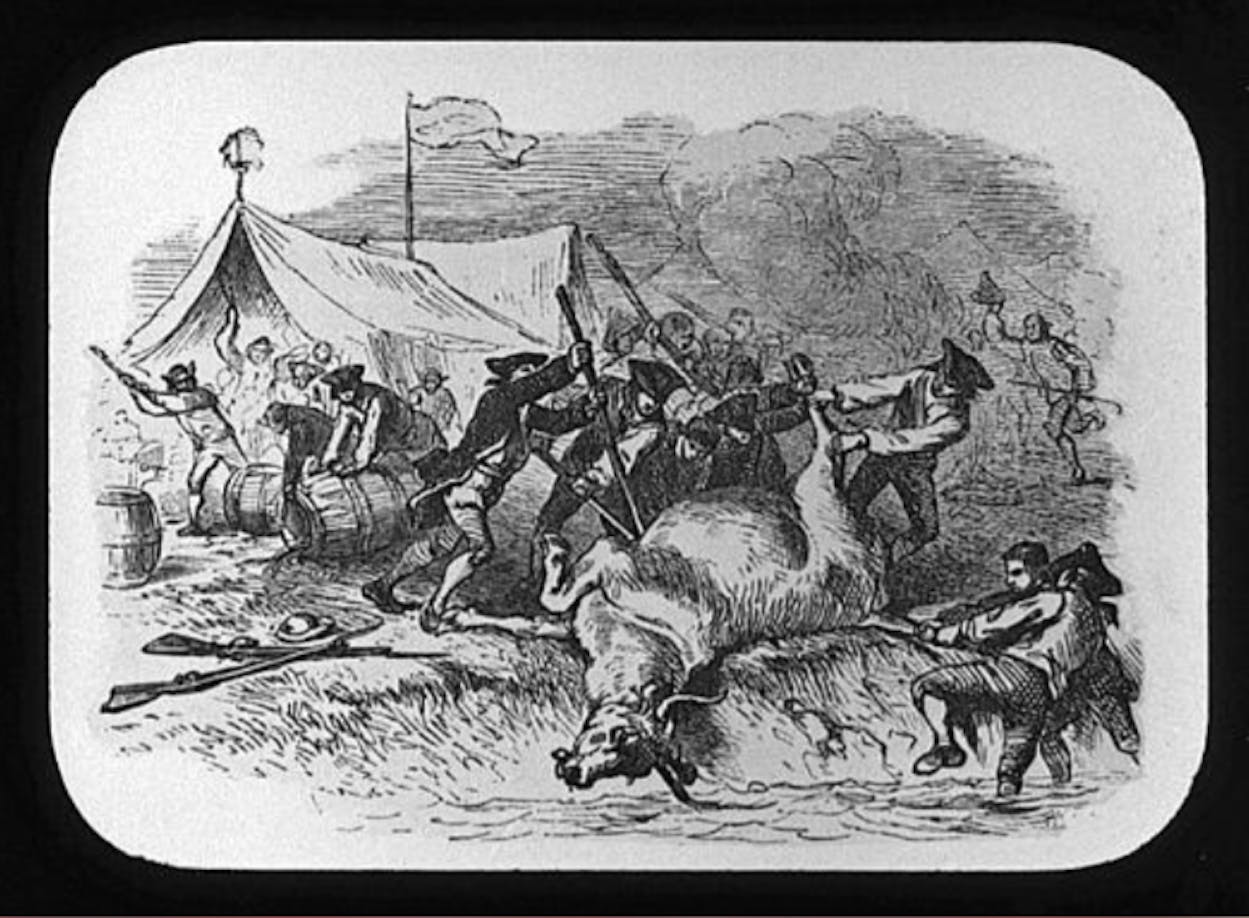

It became official later that year, and on December 19 (or December 20, because the records are unclear) Tryon planned to hold a grand celebration announcing his governorship. There was going to be barbecue, liquor, and cannon fire—always a good combination. Trouble was, tensions over the Stamp Act boiled over and ruined the day, which ended with a perfectly good ox thrown in the Cape Fear River. At least that’s the story retold today, probably thanks in part to the artwork above.

After some research I learned it wasn’t quite that simple, but first a refresher course on the Stamp Act. It’s the reason you’ve heard the line about “no taxation without representation.” The Brits were in bad financial shape and decided to tax pretty much any important paper or document in the colonies. They did this by way of a stamp that needed to be purchased and applied to legal documents, newspapers, and even playing cards. There were also sheets of paper that could be purchased with the stamps already affixed. Colonists felt the tax was unfair if it wasn’t matched with representation in the British Parliament, which the British had no plans to accommodate. As the date neared that the act would go into effect, riots broke out.

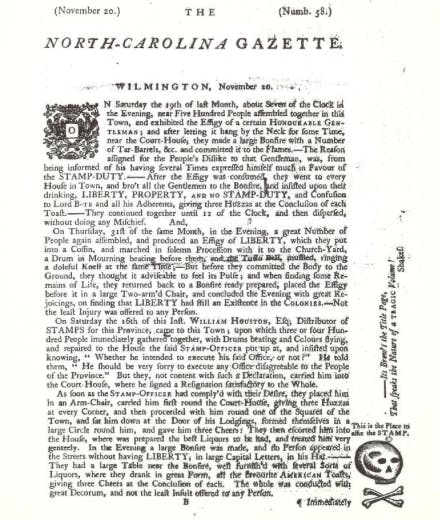

Stamp distributors, an appointed government position, were forced to resign their positions by angry mobs. Supporters of the act saw their homes ransacked in Newport, Rhode Island. The governor of New York had to flee when his home was attacked and carriages burned, and in Boston the lieutenant governor’s house was damaged so severely that it was abandoned. Down in Wilmington, North Carolina the angry crowds hung their designated stamp master, William Houston, in effigy before he even got to to town. Then, on Halloween night of 1765, a protesters, who must have had a flair for melodrama, gathered and “produced an effigy of LIBERTY, which they put in a Coffin, and marched in solemn procession with it to the Church-Yard, a Drum in Mourning beating before them,” as reported by the North Carolina Gazette.

When Houston finally made his way to Wilmington on November 16, he bunked at Governor Tryon’s house on Market Street where a marker stands today. Tryon attempted to head off the three hundred or so protestors who showed up looking for Houston, but Tryon eventually turned him over to the mob. Without much of a choice, Houston marched down to the courthouse with the mob and resigned his position, leaving Wilmington without a stamp master.

The city was also without stamps. The war ship Diligence, captained by Constantine Phipps, carried the stamp paper from England to be delivered to Wilmington. Phipps was met with an armed militia on November 28 when he tried to dock and was forced to backtrack up river and anchor the ship for months without unloading the stamped paper. Without a stamp master or stamps, any printing or distribution of documents became illegal, so we have the printer of the North Carolina Gazette to thank for defying the law to print a newspaper. You can see in the image above the mock “stamp” of a skull and crossbones under the words “This is the Place to affix the STAMP.”

The stamp business was still at a stalemate a month later, and the beleaguered governor Tryon was also in the fifth month of a long illness. Still, he went ahead scheduling a ceremony to formally commemorate his ascension to the governorship that December. From downriver in Brunswick, he embarked on the Cape Fear River in a wooden boat with the embattled Captain Phipps. They docked at the Wilmington wharf, where they were greeted with celebratory cannon fire. An ox roasted over a barbecue pit as the militia gathered to welcome Tryon, who gave a speech imploring the colonists to accept the stamps still sitting on the Diligence.

There are multiple accounts of what happened afterward, but it’s safe to say the barbecue didn’t go as planned. Most modern retellings of the barbecue repeat a few key details, including that the fully-cooked beef was thrown into the Cape Fear River. That makes the etching above, which depicts a live ox being dunked, a bit far-fetched. At least some part of the ox being thrown in the river is agreed upon by all the accounts I could find from the nineteenth and early twentieth century, but details varied on the amount of oxen, the full menu, and even the year of the barbecue.

I went in search of any written materials from 1765 and found them thanks in large part to Lindy Cummings at the Tryon Palace museum. She pointed me to a collection of Tryon’s correspondence, which included four separate accounts of the day in question. One from the Maryland Gazette in February 1766 and another from Tryon himself didn’t mention what must have been an embarrassing event, but others retold it in great detail.

The Maryland Gazette had changed its tune by March 1766 when it published this account of the barbecue:

Col. Tryon, the Governor of North-Carolina, some few days ago made a great Entertainment, roasted a whole Ox at Wilmington, and invited all the People of Consequence, his Commission as Governor was read, after which he made a Speech [in support of the Stamp Act]. This diabolical Proposal was answered with a general Hiss, after which the roasted Ox was hung up on the Gallows, where it probably hangs to this Day, the very Negroes disdained to taste the Bait of Slavery which was laid for their Masters.

After you get past the sickening direct comparison between unfair taxation and being an enslaved human, notice there’s no mention of the river. A letter from Samuel Johnston to Thomas Barker on January 9, 1766 provided even more detail about the mob. After the militia had taunted the captain and the governor with their own boat, threatening to burn it:

They then launched the Boat into the water and collected themselves round an Ox and 6 or 7 Barrels of punch which had been given by his Excell’y. They immediately broke the heads of the Barrels of Punch and let run into the street, put the head of the Ox in the Pillory and gave the Carcass to the Negroes.

At least the meat wasn’t wasted in this scenario, but the point was clearly made to Tryon that his hospitality would not placate the militia. A full eight years before the much-heralded Boston Tea Party, the angry colonists in North Carolina demanded action, and when news of this protest and others like it made it to England, Parliament acted. In March of 1766 the Stamp Act was repealed.

Tryon moved north to his new mansion in New Bern in 1770. It was dubbed Tryon’s Palace, but he lived there only a short time before leaving North Carolina for New York. It stood after the Revolutionary War and was visited by Venezuelan revolutionary Francisco de Miranda in the late 1700s. According to his biography by William Spence Robertson, Miranda visited Tryon Palace on June 10, 1783, where “the people of Newbern had just celebrated the cessation of hostilities with England by a barbecue at which rum and roast beef were consumed by the common people, the country gentry, and the leading magistrates.” His biographer added, “‘It is impossible,’ said Miranda, ‘to imagine a more purely democratic gathering.'”