Houston Wright cut meat, made sausage, and cooked barbecue at Kreuz Market in Lockhart for sixty years. He was tying sausage there before the brick building that housed the market (and is now home to Smitty’s Market) was built in 1924. He was deaf and mute by then—former Kreuz Market owner Rick Schmidt said the disability was the result of a stroke when he was nine. Smitty’s owner Nina Sells agrees on the age, but blamed spinal meningitis. Either way, they called him “Dummy.”

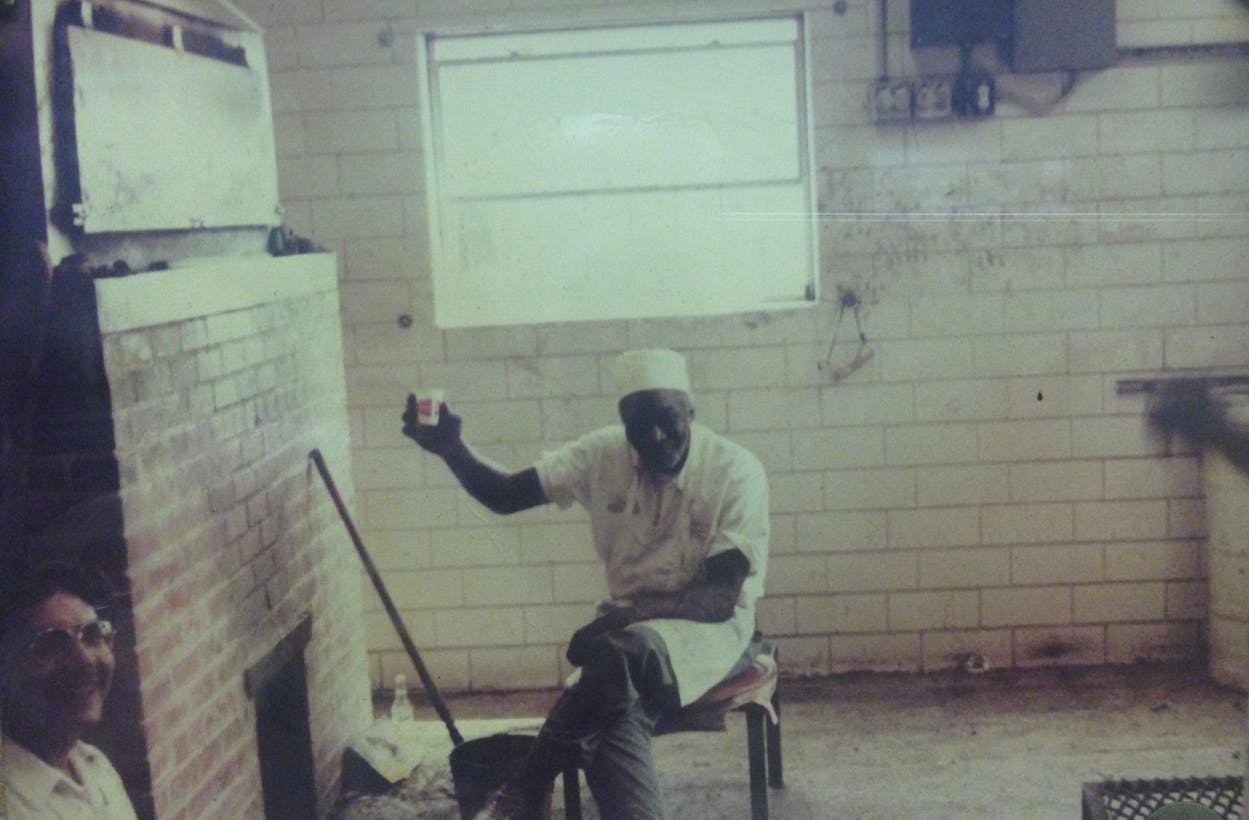

When I first noticed the collection of photos at Smitty’s pinned to a glass covered bulletin board, I asked Nina Sells about the cluster of images featuring a tall black man. She said, “Oh, that’s Dummy,” and I was slightly taken aback by the name. But she said it wasn’t meant in a mean way; that’s just what everyone called Houston Wright. Nina described those photos from the seventies that now hang behind the glass. “He would tell you a story, and that’s what I wanted to capture here,” she said. “He couldn’t talk but he would tell you things by acting them out, and we’d all listen.”

I later asked Nina’s nephew, Keith, who now operates Kreuz Market, if he had any memories of Houston Wright. “No,” he told me. I pressed again, this time asking him if he remembered a man called Dummy. Keith may not have known Dummy’s given name, but he recognized the nickname, telling me, “he was a character.”

But no one seems to know much more about Wright—or at least not about how he got started at Kreuz Market (which was called Kreuz Brothers Co. between 1911 and 1948, the time period Wright started). In an announcement of his seventy-third (and final) birthday in the Lockhart Post Register, it noted that Wright “started as a butcher’s helper.” If the dates are correct, he would have been about eleven or twelve years old on his first day at work. With age, he grew into an tall and strong man, perfect for handling the half carcasses of meat that Kreuz Market received from their own slaughtering plant.

Nina recalls when Wright worked at the slaughterhouse. “They actually butchered out east of town and he was very instrumental in the success of that.” Rick Schmidt was more blunt. “He killed animals. He skinned them and gutted them and brought them in here.” But he didn’t just bring them in as Schmidt remembers. “Dummy would show off. He’d take half of a calf and slide it off the delivery truck. He’d grab it and let it land on his back. He’d walk through the market like that. It had to weigh 250 pounds.”

In 1929, Kreuz Brothers Co. bought the Q. P. Stagner meat market in Luling. Charles Kreuz Jr. left Lockhart to operate it, and Wright went along. He continued to make that famous sausage, and Schmidt remembers the story told by his father about Wright’s brief attempt at athletics when a traveling carnival came through Luling. “They’d have a burly guy and you could pay your $5 to get in the ring with him. If you whipped him you win $100. Well, Dummy was strong, but he wasn’t a good boxer. He got in there and got knocked out.”

But it’s another story about Wright that illustrates just how close he was to the Kreuzes, who were there for him during some tough times. Wright had a day off from the market in Luling and decided to visit his girlfriend in Gonzales. He got thirsty during the eighteen mile walk, and stopped for a drink at a farmer’s well. Rick Schmidt describes the tragic events that followed his knock on the door:

No one came to the door. They hollered at him to get away, but he couldn’t hear so he knocked some more. He just wanted a drink. He decided nobody was home, so he went around the side to the cistern and drew up a bucket of water to get a drink. All the while the man inside is yelling saying he’d called the law. He took off walking back to the road and the guy shot him with his shotgun in the foot.

The Gonzales sheriff’s department found him and hauled him in for trespassing. He may have been a valued employee back in Luling, but he was also disabled black man in the Jim Crow-era South. Unable to describe his situation to his jailers, he yelled in frustration while behind bars for several days with a festering, untreated gunshot wound. They just thought he was crazy, and obviously not worth medical treatment. The dates of his incarceration are unknown, and Gonzales County doesn’t have jail records that go back that far. It had to have been before Charles Kreuz Jr.’s sudden death in 1942 because that’s who came to find him, according to Schmidt:

Finally somebody from Gonzales told [Charles Kreuz Jr.] that they had a black man down there that was just crazy. They said nobody could get near him, and that he just hollered. He had no medical. Charlie went to check because he was sure they had Dummy. When he got there, they told him “Don’t go back there. He’s crazy.” He said “If it’s who I think it is, I can go back there.” The way my daddy told me is when Charlie got back there Dummy just started crying. Charlie went back out there and cussed the sheriff’s department out. “The man is deaf and dumb, and he’s scared to death. He’s been shot and his foot’s infected.” They said “We didn’t know. We just thought he was crazy.” Charlie took him to the doctor and they had to amputate his foot at the ankle. That didn’t get it all. There was still gangrene so they had to take off his leg just below the knee. When I was a little kid, he had a peg leg.

The peg leg was eventually replaced with a prosthesis. It may have slowed his mobility, but Schmidt says his strength wasn’t diminished. “He’d take the sausage string and wrap it around his biceps about six times. He’d take his fingers and tighten them up and he’d break them just by flexing.”

Wright didn’t let this new disability hamper him any more than he’d allowed the others to. After healing up, he went back to work in Lockhart making sausage. When Edgar Schmidt purchased the business in 1948 he kept him on staff, and in his book Barbecue Road Trip, Karl Witzel described Wright’s integral role. “At the time, it was still primarily a meat market – with pits in the back and sausage-making going full tilt – orchestrated by a man known as Houston ‘Dummy’ Wright.” This was at a time when, according to the Lockhart Post Register, the local postmaster delivered Kreuz Market fan mail addressed only to “The Man Who Served us Hot Guts, Lockhart, Texas.”

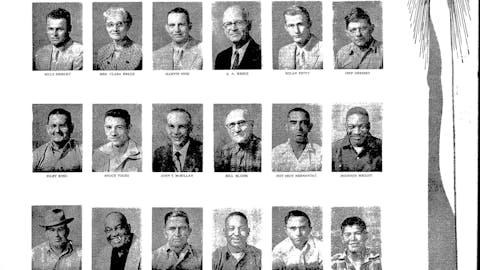

In 1955 Wright was listed with seventeen other employees in the annual Kreuz Market Christmastime newspaper ad. Among them were A. A. and Clara Kreuz, who Edgar Schmidt had purchased the business from in 1948. There was also Hot Shot Hernandez—”Those two hated each other, but they got the sausage done” recalled Rick Schmidt—and Lightning Alexander.

Lightning’s real name was Lucius Alexander. While interviewing Rick Schmidt, I asked if he was one of the barbecue cooks. His answer was succinct. “He was the cook.” Edgar Schmidt may have known his way around a pit, but he was trained as a butcher. “He could cook, but he mostly hired people to do that. As soon as someone needed something cut, he’d go help them instead of cooking.”

It’s an important reminder about our state’s barbecue heritage, and the narrative that is often repeated where Central European (white) immigrants brought barbecue to Central Texas. In the case of Kreuz Market, the Schmidts brought the operating capital and butchering skills, but even at one of the state’s most famous Central Texas barbecue joints, a black man named Lightning Alexander did the cooking. As Texas barbecue writer Robb Walsh asked in his 2000 article Barbecue in Black and White, which mentions Houston Wright, “how did it happen that we forgot blacks used to cook barbecue in Texas in the first place?”

We also shouldn’t forget that one of the most famous sausage traditions in Texas was carried on for decades by a black man with one leg who was deaf and mute. After sixty years of tying sausage—a career at Kreuz Market that lasted longer than those of its founder Charles Kreuz Sr., the Kreuz sons, or even the legendary Edgar Schmidt—Edgar moved Wright into the Cartwheel Lodge retirement facility in Lockhart where he was a heck of a domino player. He died in 1980, and though the opening line of his obituary tells you what he did—”Houston Wright, a butcher at Kreuz Market…—it doesn’t do enough to tell you who he was: a beloved member of a family who helped build up one of the most famous institutions in Texas history.