Owner: Local Yocal Farm to Market in McKinney, opened 2010

Owner: Local Yocal Farm to Market in McKinney, opened 2010

Age: 37

Matt Hamilton grew up on a ranch in southern Oklahoma, but just a few years back he was using his college degree in the corporate world. It wasn’t until 2009 that he decided to go full bore into the ranching life once again with the Genesis Beef company. After a couple years selling beef at farmers markets, it was time for a bigger move. That’s when Local Yocal Farm to Market opened just off the square in downtown McKinney. He now sells an array of steaks out of the market along with supplying local restaurants with beef. One of those customers is Top 50 BBQ joint Hutchins BBQ which buys all of their briskets from Hamilton. He may sell groceries, but when Matt Hamilton says the word “groceries” what he means is good grass to graze on for his cattle. His target is to create good fat beef the old-fashioned way – with grass.

To help navigate some of the terms used in this interview a short glossary has been provided.

Beta Agonist: Growth hormones used on cattle to increase their slaughter weight.

BMS Grade: Beef grading system used for Wagyu beef that is usually more marbled than what can be measured on the standard USDA grading system of Select, Choice, and Prime.

Cellular Grazing System: Where small portions of land are used for grazing on a rotating cycle so that each cell can recharge after it has been grazed.

Certified Angus Beef: A name brand for Angus-like cattle that are graded as High Choice. According to CAB, “Cattle are eligible for ‘Certified Angus Beef’ evaluation if they are at least 51% black and exhibit Angus influence,” which includes not having a Brahman-like hump on their back.

Daniel Vaughn: What types of beef do you sell here?

Matt Hamilton: Grass-fed beef, Wagyu and genetically certified Black Angus.

DV: Where do they all come from?

MH: The grass-fed comes from mine and my dad’s place near Durant, Oklahoma. They also come from 4M Ranch near Paris, Texas

DV: The 4M is a ranch you have a partnership with?

MH: That is a guy who stumbled in here one day and said “I’ve been looking for you for ten years.” He is an eccentric, inventor, genius guy who has a very state-of-the-art ranch. He has been developing a line of grass-fed beef without a market. He’s been working on his genetics, his ranch, and his forage program for ten years. He has center-pivot irrigation for his grass.

DV: What’s his name?

MH: David Munson. We’re moving to a stage where I’m going to take our calves and finish them there. It’s that good. We move those cattle every day or every other day on a three to five acre cellular grazing system. Those forages are managed year round so there’s something that’s fresh and in-season for them to eat year round.

DV: So, the cattle he’s raising there aren’t really affected by the drought?

MH: In a drought, even when you irrigate, when it’s hot forages don’t grow. It costs you so much money to irrigate. You just don’t do it unless you have it.

DV: Isn’t the theory about grass-fed beef that the feed doesn’t cost anything since it’s already growing?

MH: That’s the theory. I’ve always said the best thing for the grass-fed beef market is eight dollar corn. Four dollar corn is hard to compete against. It can just put the pounds on cheaper.

DV: As a grass-fed beef producer, are you an ethanol proponent?

MH: No. The bad part about ethanol production is that corn goes into the ethanol plant, but corn gluten and dry distiller’s grain comes out. Those are now an even cheaper government subsidized feed solution. Now that’s the majority of what is getting fed to the cattle. It’s not good for them because it’s been stripped of a lot of essential nutrients and it’s high in sulfur.

DV: You just can’t win. What made you want to start running this meat market, anyway?

MH: The dream was this: I’m going to raise cattle in Oklahoma and come to Texas and sell meat on the weekends at the farmers markets. God had a different plan. Selling meat at a farmers market is not a very good winter income. It’s a pretty tough income in the summer too, and I can only sell frozen beef. Marketing was a problem, and so was processing. My processor back then delivered meat to me that was unsellable. I came here and bought the building and fixed it up into this market.

DV: Why grass-fed beef, specifically?

MH: My dad is seventy-two. I was their youngest by a big stretch. He grew up when everything was organic in the forties. He’s been through this modern revolution. He has a feed mill and a farm center where he sells chemicals and fertilizers, but he knows the way we’re doing it now is how he was doing it back then. My dad has told me this my entire life. “We only have one thing to sell off of our ranch. Grass.” We could cut sod, bale hay, or harvest it with a steer and sell beef.

DV: How do you deal with the seasonality of grass and the recent drought?

MH: Cattle are in one of two phases. If the weather’s nice and they have the groceries available, they’re going to be in a fat storing phase. When an animal is just maintaining or losing weight, they’re doing that either because of the environment – it’s too hot or too cold – or because their aren’t enough groceries. The heat really affects us in the summer. As the heat hits, it doesn’t really matter if the groceries are available. Just like you and I don’t really want to eat a lot when it’s a hundred and eight degrees, they don’t want to eat either. They just want to maintain.

DV: How do those phases affect the quality of the meat itself?

MH: When they’re just maintaining or losing weight, they start breaking down and reabsorbing fat. That’s where the meats gets gamey or strong – all of those bad connotations you’ve heard about grass-fed beef. If they’re moving forward the meat is mild.

DV: They actually lose their marbling?

MH: Yes.

DV: So if they have the grass or groceries they need, what is the best time of the year to slaughter them?

MH: We’re good here October through June. July and August and early September are struggle months for us. If they’re already in good condition coming out of June, then we’re okay.

DV: How quickly does the marbling begin to fade?

MH: These cattle just haven’t developed it. Last summer was a very hot and dry summer. We didn’t get the right kind of forage into them that they needed at the right age, and they’ve been in a very lean phase coming through the winter.

DV: What age is the normal grass-fed steer slaughtered?

MH: Two years. We like twenty-four month old cattle. That’s about six months longer than the average commodity beef. The Wagyu we actually harvest at twenty-eight and thirty months. They grow very slow.

DV: Wagyu beef has a lot of marbling. Does it take that long for the marbling to develop, or just to get them up to the desired weight?

MH: We’re trying to store healthy fats like Omega-3’s. They genetically store that kind of fat, but they really start storing it later in life. The Omega-3 shift occurs in them in the later months. That’s when they go from being a Choice grade calf to way beyond Prime. Prime is only a 4.5 on the BMS grading system that used for Wagyu.

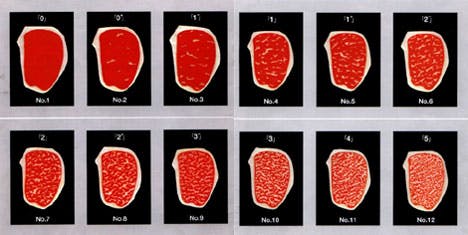

DV: What is this BMS scale?

MH: It’s a Japanese scale that they grade beef on. It’s a 1-12 scale. You hear about Kobe? It has to be a 10, 11, or 12 on this scale to be called Kobe. A 12 is 74% fat on the ribeye. We get down into 40%-50% fat with the Wagyu in the market. For comparison, Prime is about 33% fat.

DV: Where are the Wagyu cattle coming from? Are they on your ranch too?

MH: I’m not directly raising Wagyu. There are Wagyu here in Melissa at the Walking T Ranch and another ranch up near us in Oklahoma. We’re part of a grower group for Wagyu that had ranches in Texas, Oklahoma, Kansas, and Nebraska that all send cattle in to a plant in Omaha where they’re processed.

DV: You don’t process them here?

MH: No. I fought that for a while because I wanted to kill them and process them all here for the market. The problem with Wagyu is that if I kill ten of them some are in that super high marbled grade, most of them are in this middle-of-the-road, while a few will be high choice or low prime. I had to sell all that beef at the middle-of-the-road price, so if you came in one day and got a BMS 10 it was at a rocking cheap price. The next time you might get the middle or low end. When we got down to the low end here the restaurants wouldn’t take them, so I had to have a fire sale to get rid of them here at the market. Now that we have them processed in Omaha, those top grade cattle go to export. They pay so much for them, I’d have to get $120 per pound for filets to match what these export for. We let that go. That makes the other cattle more affordable and it gives me consistency.

DV: So, even if we produce the BMS 10 Wagyu beef here, it’s not available to buy here?

MH: It will if you’re willing to pay $60-$80 per pound for ribeyes or $120 per pound for filet, but at this point the market will not bear it.

DV: What about the lower end stuff? Where does that go?

MH: There are people somewhere who like that, but if you come here you’re going to get BMS 7 or 8.

DV: You’re selling grass-fed beef among others. Is the beef here also hormone and antibiotic-free?

MH: On the Angus, because they’re drug free we’re killing eighteen to twenty month old cattle. That’s what you give up by not using the growth drugs. You can take a beta-agonist level 1 growth regulator and use that in the early stages of a calf’s life and get about a half pound a day out of him. Then you use a Level 2 growth regulators at the end to really swell them up for the last thirty or forty-five days.

DV: You don’t use any beta-agonists, correct?

MH: We don’t use any growth regulators. It takes one and a half times more energy to put on one pound of fat on a steer versus a pound of muscle. So the lean steer is more fuel-efficient. It puts on more weight with less input, but if you want fat beef you need a premium fuel. Clean meat is gonna cost. The researchers say the difference in beef quality is small. Let’s say that this growth regulator is a product of mine, and I own all the rights to it. If you’re a university, a land grant college, and you want to study this on cattle. You can’t unless you have my written permission, and I’ll only give you that written permission if I agree to the results and the testing parameters. You can’t do independent research on this stuff without my permission. It’s illegal and I’ll sue you to hell and back. That’s the hypothetical situation.

DV: You also market purebred Angus here. What is the importance of the genetically verified Angus?

MH: The Hartley’s were pureblood Angus breeders out of Chalk Mountain, Texas near Stephenville. In 1992 they got really frustrated with the Certified Angus Beef program. They didn’t like marketing beef just because they were black hided. They decided to raise purebred Angus cattle. They struggled for a lot of years, then a company out of Austin called Cryogen contacted them. They do DNA testing and asked the Hartleys to use their technology to market their meat. They DNA test every calf. They have to be 90% Angus genetics to qualify in this program.

DV: What is the real benefit of using purebred Angus, or is it just marketing?

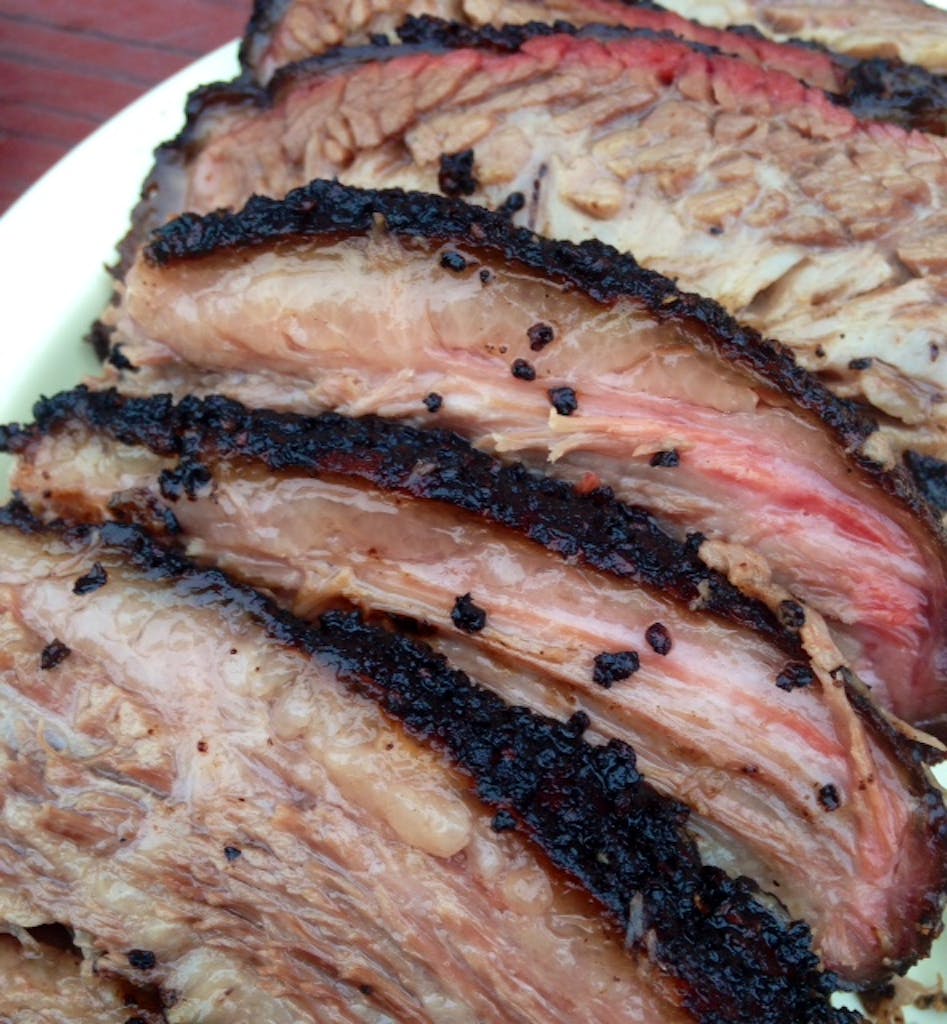

MH: Quality and consistency. The Angus breed is great. The cattle are so closely related so you end up with a very close outcome. Our customers tell us that they see the difference, especially in the briskets.

DV: In the back today you have some whole carcasses. Which of the beef types do you get in here as whole carcass?

MH: We occasionally have whole carcasses of Wagyu, we always do carcasses for the grass-fed and we never have carcasses of the DNA verified.

DV: Who processes that for you?

MH: There’s a small processor in Omaha that has the capacity to about a hundred twenty head a day. They process most of our Wagyu and send that back here. We take in about forty to sixty animals per day from them. The Hartleys use that processor as well.

DV: Why not process them all here?

MH: The efficiencies of using a larger plant like that are numerous. The hides that come off the cattle, I get $25, they get $85 because of the volume. They can sort them and sell them by the semi load. I pay someone to come haul off my waste. At the big plant they get paid for it. They process the cattle more efficiently too with the line cutting. All of those efficiencies are enough to offset the cost of the processing. If you take a thousand head of cattle to National Packing and have them contract pack those, they’d do it for about $275 per head. On a real good day your drop credits will completely pay for that, so you could be out the door with boxed beef for free.

DV: Are you a USDA certified processing facility here?

MH: In Trenton right down the road we have a state certified facility, so within Texas that’s just as good as USDA certified. I can ship anywhere in the U.S. to sell directly to a consumer. If I want to sell to a restaurant they have to be in Texas.

DV: How many head of cattle do you go through in your total operation here at the market?

MH: On the grass-fed beef we’ll run anywhere from two to eight head per week depending on the season. That’s quite a range, but that’s the reality. On the Wagyu, just for our operation here we use ten to fourteen animals per week. On the Angus we probably buy four to five head worth of Angus per week.

DV: How much of your business is done with restaurants versus selling it out of the market here?

MH: We’re about fifty-fifty. Wholesale and retail go together really well. When people aren’t eating out, they grill at home.

DV: What have you seen as the most popular cuts purchased here?

MH: We’ve really developed great carcass balance through our steak class. The consumer comes to us wanting ribeyes, strips and filets. That’s all they’ve known. Once they come to our steak class and we show them the middle cuts – the flatiron, the bistro filet, the chuck eye, the sirloin coulette, and one we cut here out of the chuck called the McKinney steak.

DV: You put on a class here just to educate consumers about these varied beef cuts?

MH: Yes. We’ve had almost four thousand people come through that class. Most of them who take that class will buy those middle cuts. The sirloin coulette is one that we’ve over-created demand for. We won’t wean everyone off of filet. If they want to pay $44 per pound for Wagyu filet, we have it.

DV: You’ve been in the grass-fed beef industry for a while, and you’ve seen the benefits and challenges with growing cattle this way. Is this the future of beef?

MH: It’s a part of the future. I don’t know how big of a part. If our industry – North Texas and Southern Oklahoma grass-fed beef producers – wanted to get to ten percent market share in the Dallas/Fort Worth area, we need to process fifteen hundred head of cattle per week. Right now if we all pulled together we could do twenty or thirty head per week, and it wouldn’t be the quality we need. But here’s the good news. We have not had professional ranchers doing this. I feel like me and a couple other families are the first ones with professional ranching background to get into the business. It’s just like NASCAR. If you don’t have a professional team you’re not going to compete. Three years ago I got made fun of at the hometown coffee shop. Now they go “Hey, I heard you were in the Dallas Morning News. That deal’s going pretty good, ain’t it? What would it take for you to buy calves from me?”

DV: Do you think the message about grass-fed beef is more easily accepted from you, a guy with a cowboy hat and a thick accent?

MH: It comes off a lot cleaner because I can walk the walk and talk the talk. They can’t say I’m the hippy who came in here to buy the old Johnson place that they can call a quack.

DV: You have a premium product here at a premium price, so I’m guessing the increase in commodity beef prices has helped you out.

MH: It has. I has really closed the gap, and it’s getting closer and closer. We’re not affected by their same market forces either. The things that will make us competitive is a processing plant that can do a hundred head per day in the Southern Oklahoma/North Texas region, that’s what will close the gap.

DV: You think that will allow you to compete with the big time processors?

MH: I had the CFO of National Beef in here. I gave him a nickel tour, and he said “what are you getting paid for your drop?” I told him “we pay a company twice a week to haul that off.” He says “I operate my plant on that, how do you give that up?” I said “That’s why I’m more expensive than you are.” What I have to pay someone to haul off is what he uses to pay his plant’s operating costs. That puts it into perspective.