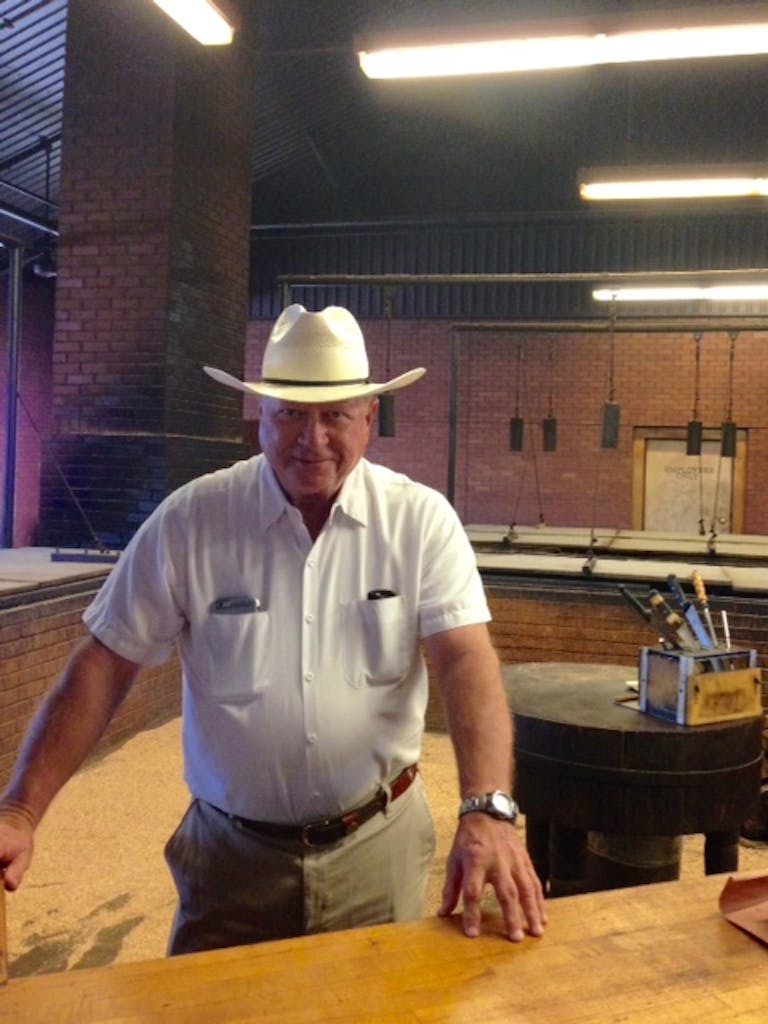

Former Owner: Kreuz Market; Opened 1900 (current location 1999)

Former Owner: Kreuz Market; Opened 1900 (current location 1999)

Age: 69

Smoker: Indirect Heat Wood-Fired Pit

Wood: Post Oak

Rick Schmidt owned Kreuz Market from 1984 to 2011. He bought it from his father Edgar “Smitty” Schmidt, and sold it to his son Keith. Rick took a momentous step in moving the business from its previous home of ninety-nine years, and Keith is seeing it through its first expansion to a new location in Bryan that will open in a few months.

I sat down with Rick at his custom made table at Kreuz Market which is reserved for Rick, and Rick alone. We discussed the one hundred fourteen year history of Kreuz Market by examining how the business evolved from a grocery store and meat market into a barbecue joint. Then Rick shared how the staff, the menu, and anything else has changed through the years. Our conversation continued for a long while, so of course we got into the well documented rift between he and his sister Nina who owns Smitty’s Market up the street. Rick shared enough for a two part interview, so this first portion covers his time in the original building before the business was moved in 1999. The negotiations between he and Nina, and the subsequent years in the new building will be covered in Part II next week.

Daniel Vaughn: Are we sitting at your own personal table?

Rick Schmidt: Yeah. I had one of those six-seater tables here, then last year, Lynn Wilkerson who did our menus, he showed up one day and had made this for me. It’s called the Rick Schmidt round table. Keith [Rick’s son and current owner of Kreuz Market] told me I should take it home, but I want it here. This chair here is mine too. It’s a $10 chair I bought at an office supply deal. I have a bad back and this thing makes it feel better. It’s the best $10 I’ve spent.

DV: How often do you come into Kreuz Market?

RS: When I’m in town, almost every day around the noon hour. It used to be in the afternoon I had some friends who would come around 4:30. We used to close at 6:30, so it was hard to get inebriated in that length of time. But then a few of them died and the beer joints here in town started to hire some pretty girls. It went away, so I just come down at noon. I still enjoy it. Keith lets me eat, kinda like feeding an old racehorse. He’s doing a good job and I’m proud of him. It’s hard to believe, but it’s been three and a half years since I retired.

DV: Were you able to let go of it?

RS: Yeah. Keith was with me long enough. He has his things he wants to do, but I’ve been in his position. I grew up working in the market a little bit, went off to college and played baseball. I had a baseball scholarship to TCU. I loved that town. If I had to live in a city, I’d go to Fort Worth. Cowtown is a good name for it. After college, I started out as a food rep for Oscar Mayer. Then I worked for H. J. Heinz. Then one of my customers hired me and I became a commissioned salesman in Houston. I sold frozen foods to restaurants and hospitals. We did such a good job of kicking Sysco’s butt down in Houston that Sysco bought us. They said they weren’t gonna be bad to us, but they cut our territories and made it hard to make a living. I transferred to Sysco in Austin. Then the same stuff happened. They cut my territory, so I went to work for one of their competitors, Labatt Foods out of San Antonio. I was doing well, but six months into it my dad gave me a call and said “I’m gonna sell the market.” I called my brother Don. He was working in real estate in San Antonio. To make a long story short, we bought it, but it took a couple years to put the deal together.

DV: How long did it take you to make the decision to buy it?

RS: It was immediate. Don was making good money and I was doing well too selling frozen food.

DV: Did you ever feel like you were on the dark side selling frozen food?

RS: No. It made a good living. Sysco has everything. I was working for Heinz when Johnny Ball owned Zero Foods and the Rosenthal family owned Food Service Corporation. They put their stuff together and came up with Sysco. That was in the early seventies. I saw Sysco grow and get arrogant.

DV: Was Lockhart in your territory when you worked out of Austin?

RS: Yeah. I had a few accounts.

DV: Was Kreuz Market one of your customers?

RS: Yes. My dad was tough on me. I had to hit the right price or I wouldn’t get the business.

DV: What did you sell to your dad?

RS: Mostly meat, shoulder clods and briskets, and wheels of cheese.

DV: Do you remember the beef prices from back then?

RS: Briskets were $0.79 per pound and on up to $0.99. When they hit $1.00 it was big news. Clods were around twenty or thirty cents higher. Now that’s changed and briskets keep going up.

DV: I guess you need to push the clod a little more.

RS: We don’t really push anything. For a long time, the clod was it. Especially back when we would bone out our barbecue meat. We used to have our cattle butchered. We would bone the forequarters, and even some of the hind quarter meat, and sell it across the pit. We would bone out some shoulder and take the seven bone out of it. We sent it through a jet net to hold it together so it would cook evenly. We would jet net the boneless chuck, the shoulder, and the prime rib. We started buying shoulder clods from Massengale Meat in Austin in the seventies. Nobody knew what a clod was then. You mention clod, and people thought you meant a clod of dirt. It’s not a real appetizing name. We had brisket, which was fat meat, and we had shoulder and chuck. When that ran out we’d sell the clod. No matter what was on the block, people would still ask for brisket. To them, meat on the counter was brisket.

DV: The menu has brisket and clod on it now, but what was on the menu when you were cooking the whole forequarters?

RS: They’d say “Give me lean beef or fat beef.” Then we started supplementing shoulder in for the lean meat.

DV: You can order dry or juicy sausage here. What’s the difference?

RS: If you ask for a dry ring, that’s one that has cooked down a little more.

DV: A little of the fat is cooked out of it…

RS: Juice. Some people will tell me “That sausage is greasy.” I tell them “No. It’s juicy.”

DV: Is it a German sausage?

RS: I wouldn’t have been able to answer that until about twenty years ago. The formula came from the Kreuzs. They came from Germany, but I’d never eaten a German sausage that tasted like that. Generally it was pork with some garlic. They all had a different taste. People would ask me if it was German sausage. One day a charter bus came through at the old place. It was a big group of German citizens who were touring Texas, or maybe even the whole US. They went through the line, took their food upstairs and ate. A lady came and asked me “are you the owner?” I said “Yes ma’am.” She said “I want to tell you that your sausage is the only sausage that I’ve tasted here that reminds me of my hometown.” She said “Each little town has a wurstmeister, a sausage maker, so each town has its own flavor.” She said “Your sausage tastes like my hometown.” So, it’s German sausage.

DV: Do you remember her hometown?

RS: No. I was too stunned that I didn’t ask. I should have.

DV: Your sausage is primarily beef with salt and black pepper. Do you also use a little cayenne?

RS: Yes. And there’s also a binder. You have to have bull flour. I had a crew that made a batch without a binder. It didn’t taste very good. It was crumbly and extremely juicy. When I cut into it, it just crumbled like hamburger meat and the juice ran all over. The binder has wheat, rice, and a few other grains. It affects the flavor.

DV: And you still make it right here?

RS: Yes. It’s all hand tied which is labor intensive.

DV: And you’re also supplying three locations of Hill Country Barbecue and two locations of Lockhart Smokehouse.

RS: And pretty soon, Kreuz Market in Bryan.

DV: I saw the foundation poured in Bryan.

RS: They set the pits the other day too. It’s getting to a point we’ll need a full time sausage crew.

DV: You always had just the one location while you owned it, so what are your thoughts about this new location in Bryan?

RS: I don’t delegate like Keith does. That was a fault of mine. If it was up to me, I’d make every ring, cook everything, slice it, weigh it, and give it to the customer. I was that much of a perfectionist.

DV: When I interviewed Roy Perez, he used another word for it.

RS: [Laughing] I know. He’s been a little hard on me sometimes, but I had to be hard on him too to get him where he’s at.

DV: Would you agree that you were hard to work for?

RS: Yeah, because I wanted it a certain way. Part of that goes back to my dad. My dad didn’t think that anybody could run it as good as he did. I came back to buy the place in 1982, but it took two years to get the deal done. The reason it took so long was that my sister [Nina Sells] fought us the whole way. At one point my brother gave up and went back to San Antonio. I told my dad I was going back to work for Labatt. It wasn’t working. I told him to give it to Nina or sell it to her. He said “Well, she can’t run it.” So I said “Then you have a problem.” So anyway, by the time my brother and I bought the thing in 1984, my dad was hoping in the back of his mind that I’d stump my toe. I’m the younger brother, but I was the lead on it. I was more in the sausage room. I was the fastest sausage stuffer and tier. I could do anything. I didn’t ask anyone to do anything I wouldn’t do.

DV: Hadn’t you gotten rusty after all those years of selling frozen food?

RS: No. It’s like riding a bicycle. Back then my dad and the Kreuzs always used beef rounds to make the sausage. Packerland was the last supplier. They started getting their beef guts from South America. Down there they used seashells for roughage in the cattle feed. The guts had little bitty seashells in the lining and you can’t wash it out of there. I couldn’t use them and Packerland said that’s the only option they had. I checked all over everywhere and there wasn’t any.

DV: Did you switch to pork then?

RS: Yes. We always stayed way ahead on beef casings. You’d get them in and salt them. Somebody would have to stand at the sink and turn them. You’d stick your finger in there and flare them out and run water in there. It would suck the water all the way through the casing and turn them back out because they came inside out. Then you’d lay them out and cut them. We’d cut them in fourteen inch strands, throw them in a pile, and four or five people would sit around a table like this tying string to one end. Then we’d salt them and put them into barrels. We’d try to stay a few barrels ahead all the time. When we made sausage we’d get a bucket or two and soak them. Then we’d stuff them. The stuffer would pull them on and stuff them and slide them over. Another person would grab the tail end and the string, flip them over, and tie them off into rings. That’s the way we made sausage. The big labor was that first tying.

DV: Did that change when you went to pork casings?

RS: I had to do something fast because we were running low on beef casings. I talked to Roy Jeffrey who ran Luling City Market. Roy and I were in school together. He was here visiting. Snookie is what we called him. I said “Snookie, we’re going to have to go to pork casings.” I went down to Houston one morning and he showed me how they made sausage. You stuff the whole string but leave a gap between each ring. Then you take a ring knife like they use on sewing machines and cut at the gaps so they’re open on both ends. Then you anchor the string, pick up a piece of gut and lay it on top. You come through one time, pick up the other side, tie it tight and you’re done. You can make a whole line of them until the end of the string, then you take a knife and cut the string at the end. The process went a little slow at first because we had to get used to it. My employees fussed about it. We’d take three and a half hours to make four tubs of sausage the old way. This way it might take five hours. My dad came in and asked one of the old time ladies that worked for us “How do you like this new way of making sausage?” She said “Oh Smitty, it’s horrible. It takes too long.” He said “That’s what I thought.” I could hear him around the corner. Then he asked how everything else was going, and she said “Not good at all. I’m not getting my hours anymore.” Well, that’s because we didn’t have to sit around turning and tying the guts to fill those barrels anymore. Pretty soon we got better at it. I’d get in there just to give them a push. It worked. The thing that goes back to is why I was such a stickler. I had my father looking over my shoulder. He was just waiting for me stump my toe. If any employee did anything that a customer complained about, I was going to catch hell.

DV: If he was willing to sell it to you, why did he feel that way? Wasn’t he done once he sold it?

RS: Physically he couldn’t work anymore. He was mad about it, and he wanted to think that nobody else could run it but him. The banker said the same thing when we asked for a loan. He called me back the next week and he said “The board just doesn’t think the place can run without Smitty.” I said, “Well, I’ll show you then.” I ended up running it for two years for my dad. At the end he had more money in the bank than he’d ever had in his life. That’s when he said “I guess you know a little bit about what do around here, so I’ll finance it myself.”

DV: So the two year negotiation time was really just you showing your dad you could run it? That’s a long audition period.

RS: When I took it over he had no savings in the bank. He was paying his bills, but about three months of running it we had too much money in the checking account. I asked him what he did with the money when it got that high. He looked at me and said “We’ve never had that much money in the checking account.” I was straight salary at the point, and he didn’t pay me much. At first I had threatened not to come because of the big pay cut I had to take. Nina’s husband J.D. Fullilove worked for my dad for ten years. He always had a big wad of money in his pocket. He was the manager before we took over. My dad said he was going to run him off, but I said “Dad, you don’t want to fire your son-in-law. Let me take over and let me deal with it, and you won’t have that stigma.” That night my dad called me. “I can’t stand it. I fired him.” He said he didn’t have any help, so he needed me and my brother to come help. I had to give my notice, so I worked my route in Austin, and came down to work for him on nights and weekends. I did that for two weeks before I started running it. The first thing I did was make them balance the registers. The employees were so mad at me. That’s how we got the checking account up to $60,000. He said “That’s great. We’re really making money.” I said “Well I’m not.” So he decided that after we paid the bills and kept some money in the account to operate off of, I would get 25% of what was left. It more than doubled my salary, so I had a real incentive.

DV: But it sounds like your real incentive was just to prove your dad wrong.

RS: And to prove me right. That’s why I had a quick temper.

DV: When did your dad pass away?

RS: In 1990.

DV: Did you ease up without him looking over your shoulder?

RS: No. I never did. He never once told me I did a good job. Me and my older brother both pitched at TCU. Never heard him say good game or anything. He was just an iron ass. He was a good man. He was a volunteer fireman for thirty-six years, and a good member of the church. He had a lot of friends, but he rode us hard. Our mother died in 1960 of leukemia. I was fourteen, Don was nineteen, and Nina was nine. If he told us once, he told us a hundred times, “I promised your mother on her death bed that I’d take care of Nina.” Our mother was an old German gal. She was a working person. After that he married a great lady, Alma. They were married twenty-five years before he died. She and her first husband were friends of the family, and her husband died in a car wreck in Austin. They had the same friends and they got married in 1965.

DV: Did your relationship with your dad change the way you deal with Keith?

RS: Yeah it does. I’d been in his position, so when he wanted to do some things he kept asking my permission. Finally I told him that I wouldn’t put any weight on him. We made the deal, and both of us were happy with it. When he needs or wants some advice, he asks me.

DV: How old were you when your dad first bought Kreuz Market?

RS: Three. Well, he took it over in 1948, then bought it in 1951.

DV: Do you know what was on the barbecue menu then?

RS: It was sausage that was the big seller, then any other cuts of meat. There was the shoulder, the chuck, and he’d take round steaks and slice them about an inch thick. That was the worst barbecue in the world, this round steaks. We boned out hindquarters and we’d get to the kidneys. He’d put them in the sausage, and say “That’s my profit.” It was edible, but to cook a kidney, you’ve got to boil the piss out of it. [laughing]

DV: I guess your story about the round steak tells us why barbecue comes from the forequarter.

RS: The forequarter is the best part of the animal anyway. It tastes better. The round is better off as hamburger.

DV: I’m guessing there were no pork ribs.

RS: No. Every once in a while we’d get long on pork chops, so he’d cook them. We might have three pieces of pork every day. The people who knew would get there early to get the pork chops. We also sold brisket and prime rib just like the round steak. We called it fat meat. Dad would cook neck clod too. It’s lean and the grain goes everywhere. It looks good, but it’s alright. The shoulder clod’s great too, but the grain changes about three times in a clod.

DV: When did you stop serving cuts like the chuck here?

RS: That stopped when we started cooking more clod. We didn’t sell the chuck roast in the meat market, so it went into the sausage.

DV: When did you start using boxed beef?

RS: That was the early seventies. That’s when we moved to the shoulder clod. We started buying brisket shortly after.

DV: Did the briskets have bones in them?

RS: No. The brisket was always boneless.

DV: Did the menu still say brisket and clod?

RS: It just said barbecue, fat or lean. Before my time, back in World War II when they ran out if their allotment of beef, they cooked chicken and goat. After the war was over, they went back to beef.

DV: Did you have beef ribs?

RS: No.

DV: When did pork ribs get added to the menu?

RS: Not until we moved up here. I wanted to add them to the menu at the old place, but we didn’t have enough pit space. We had the space up here. I did some experimenting with different sizes. I weighed them, cooked them, then weighed them again to get the yields. I picked out the best one which is a 4- 4 1/2 pound spare rib, the big ones.

DV: What was the percentage of bone and waste?

RS: When you buy one of our pork ribs, the bone that you have left over will be between fifteen and twenty percent of the total.

DV: When you were growing up, did you think of your dad as someone who owned a barbecue place or a meat market?

RS: Both. Well it was a small grocery store then in an old building. I would ask him what he was going to do with the building before it fell apart. He said he’d just hold onto it as long as it would stay up. In that big gravel parking lot he talked about building a supermarket. He wanted something like the Blacks had at Northside Market up the street. He had the plans drawn up. He didn’t buy that parking lot for parking. Fortunately, he didn’t do it.

DV: But he had his own business.

RS: It was a big step. I remember taking a ride up to South Austin to Bluff Springs where my grandparents lived. They were proud as punch on a Sunday afternoon. We drove up there and I saw my mother and my dad hand grandpa an envelope of cash. He had loaned them money, and they paid him back. I remember grandpa saying “Y’all are the only ones that paid me back. The rest of them think it’s a gift.”

DV: What did your dad do before he bought the place?

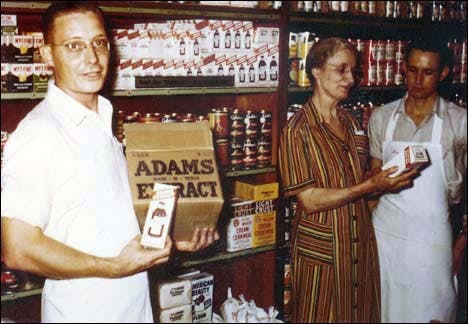

RS: He worked for Kreuz Market since age fifteen. He was twenty-eight when he bought the market. A big grocery store chain out of Austin had come down and offered my dad a job to run their meat department. He liked the fresh meat business more than the barbecue side.

DV: Did he cook?

RS: He could cook but he hired people mostly to do that. As soon as someone needed something cut, he’d go help them instead of cooking. I like the fresh meat business too, but there isn’t much money in it.

DV: That grocery store job was a pretty good job to pass on.

RS: Yes it was. He even gave the Kreuzs notice. At the time there were two Kreuz brothers and their brother-in-law. Teddy Kreuz was the mainstay, his brother Alvin which they called Mr. Molly, and their brother-in-law Hugo Prove who was an old time bartender from Houston who married their sister. Mr. Prove was the sausage maker, Mr. Molly was the meat cutter, and Teddy was the office man who took care of everything. They had a black guy back then named Lucius “Lightning” Alexander that took care of the barbecue.

DV: Was he one of the cooks there?

RS: He was THE cook. He died in the fifties [1957], but he was there a long time before then.

DV: What about other employees?

RS: There was Houston Wright. He called himself Dummy. He was a butcher. He killed animals. He skinned them and gutted them and brought them in here. He cut up meat for sausages and trimmed out meat for barbecue. He also made and tied sausage, and he cooked sausage. Hot Shot Hernandez was a Mexican, He was the other sausage cook. Those two hated each other, but they got the sausage done. Walter Palmer was another guy, but I never met him. Up in the meat market was Nolan Petty. My dad spent a lot of time up there too. There was another guy who worked there stocking shelves and waiting on the counter. His name was Gary Woods. He went on to become Red McCombs right hand man [and the president of the San Antonio Spurs and Minnesota Vikings], so he did well for himself.

DV: Did Kreuz Market have their own live animals back then?

RS: We had our own feedlot and we had stocker cattle that we fed out.

DV: Where was that feedlot?

RS: It was one mile out on Highway 20 on the right. The old slaughterhouse is now part of a garage of a house that’s there now. Dad sold it.

DV: What are your first memories of working at Kreuz Market?

RS: I guess I was eight. My mom made me a little apron. I didn’t do anything but sweep and stock shelves. When I got into high school, my dad had a deal with us. As long as we were playing sports we didn’t need to work at the market. During baseball and football season we didn’t work. During the summer we’d work, but usually is was some project that needed to be done. The first summer I was in TCU I came home and my dad had bought a building next to him that he needed torn down. He hired a friend of mine and I, and we took a few sledgehammers and took it down. He paid us minimum wage. We took the nails out of the wood and tin. Farmers would come buy the stuff. Once it was all sold, my dad took our wages out of the total and gave us the rest of it. It turned out to be good summer job.

DV: That took the whole summer?

RS: Yep. Tearing down old Sam Stein’s.

DV: Do you have any idea when the brick pits were installed? Did they always have the offset pits?

RS: They were always like that. They were sheet metal lined. They’ve been rebuilt. About eight or ten years is all we’d get out of them. There was sand underneath to buffer the concrete from the heat. I hated the sheet metal lining too. After my brother left the business in 1997 and I was still trying to make a deal with my sister to buy the place, I had plans to go back in with steel lined. You have to tear all the brick and sheet metal out, then get the sand and all the grease out. It was rank. The only thing that keeps the grease from stinking is firing them up every day. If you let those pits go a week you won’t be able to walk into that building.

DV: Was the post oak always the wood of choice?

RS: Yes. That’s mainly because we’re on the southern tip of the post oak savannah. There’s a lot of blackjack here too, but it’s no good. I’ve never cooked with live oak. It’s fortunate that we like the taste of post oak.

DV: What about the sauce. There’s hot sauce, but never any barbecue sauce.

RS: The hot sauce was in the meat market. It sold for a nickel a bottle. We didn’t have barbecue sauce and weren’t intending to get any. Customer No. 1 would come in and get their barbecue. They’d go into the market and get their cheese before going into the dining room. Well, there wasn’t a dining room, just the hallway there. They’d also buy an onion, maybe a tomato, and bottle of Gebhardt’s hot sauce. It was the best. They ate their meal, but left some in the bottle. They only paid a nickel for it, so they left it on the counter. Customer No. 2 came along and sits down and uses the hot sauce. Sometime later customer No. 2 would come in and there wouldn’t be a bottle there. They’d get up and ask Smitty where the hot sauce was. He’d say “We don’t put it on the table.” And they’d say “Well, it was here last time.” He got so tired of hearing that, he just started putting the hot sauce on the table because it was so cheap. They stopped making Gebhardt’s so now we use Crystal hot sauce out of Louisiana.

DV: Never a thought about serving barbecue sauce?

RS: I thought about it, but not for long. We go to a lot of effort to get the flavor of the meat through the seasoning and in the pit with the right wood. I don’t want to cover it up with anything. I recommend you try the meat without it first.

DV: Do people bring in their own sauce?

RS: Sometimes, but they get looked at awfully strange. I don’t mind.

DV: Has the seasoning always been salt, black pepper, and cayenne?

RS: Yes. It’s about the quality of the salt and pepper that we buy. Getting the right pepper is a big part of it. My dad told me that if pepper makes you sneeze, it’s dusty. Black pepper is a big flavor in our sausage too.

DV: The knives chained to the counter, those were chained down to keep fights from happening, but wasn’t it really to keep the knives from leaving?

RS: That’s the ultimate part, but it was a bit of a deterrent. Used to be that there were seven beer joints right around where Smitty’s is now. On a Saturday afternoon it got pretty wild. The drunks would get hungry and come staggering in. We didn’t take any s— from them.

DV: Were there a lot of other barbecue joints in Lockhart at the time?

RS: Long before my time, every meat market had a barbecue pit. So there were as many as a dozen in town. My father’s father was a meat cutter, so he worked for several of them. He was the meat cutter at Northside that the Blacks owned. One of the meat cutters we had here had worked with my grandfather. He’d say “Mark Schmidt could cut a round steak so thin, it didn’t have but one side.” That was the signature of a good meat cutter.

DV: During the lifetime of Kreuz, was there a gradual shift from meat market to barbecue joint, or was there a sudden change?

RS: It was gradual. When I got out of college in 1969, my dad didn’t have a register that would calculate meat and grocery sales. I kept track of grocery sales in a notebook for about a month. I had the invoices. At the end of the month we’d lost about 25% of what he bought. It was bad for shoplifting. He said “I never did like groceries anyway.” We put up a sign for 25% off the first week, 50% off the second, and had a fire sale the last week. That’s when we became a meat market.

DV: You said your dad passed away six years after you bought it from him. Had he retired by that point?

RS: He retired from the time that we bought it.

DV: Was there anything to mark the retirement like a party?

RS: No. Not really. We did have a party for my brother, Don when he retired in 1997. He knew what was coming up with Nina and he didn’t want to be part of it.

Part II is coming next week and will cover the big move down the street to the new building.