Co-Owner/Chef: Smoke; Opened 2009

Co-Owner/Chef: Smoke; Opened 2009

Age: 39

Smoker: Wood-fired Offset Smoker

Wood: Various

Tim Byres is a man who is hard to pin down, mainly because he despises labels. He has been chef, pitmaster, author, culinary diplomat, and almost a food stylist. Six years ago he opened Smoke in West Dallas along with Chris Zielke and Chris Jeffers, and earlier this year they opened the doors to a new location in Plano. Things are going well for the team.

Although its name implies barbecue, Smoke’s menu was diverse from the outset, and remains so. You’ll find seafood, paté, and a huge burger alongside the smoked meats, but Byres doesn’t obsess over brisket. “I get it that everyone is going to judge us on our brisket. This is Texas. If it is or isn’t better than the next guy’s, that’s somebody else’s opinion. Nobody’s going to die if we’re the best or the worst.”

Byres feels more comfortable seeking out the community aspect of barbecue rather than the competitive side of things. He’s certainly happy if you enjoy his smoked meats, but he’s doesn’t much care if you liked the stuff from the joint down the street any better. He just cares that you come back to Smoke.

Daniel Vaughn: You’ve done a lot of wandering as a chef. Where did it start for you? When did you realize you wanted to do this kind of work?

Tim Byres: It’s weird. My story could be told in a lot of different ways. There’s the barbecue story and the story of being an advocate for American Foodways. My background was this French fundamental training. I can have a conversation that’s wider than brisket and ribs. I always knew I wanted to be in the restaurant business. When I was sixteen I was working in restaurants and I was attracted to the energy. It’s like being on a football team. Then there are the customers. Some are having a good time and some a bad time. You can see how to turn that bad time around. When I started looking into colleges I wanted to open an Irish pub. I found culinary school because they teach the business side too. I wanted to go onto a hospitality degree after that, but I got into the system of high caliber restaurants.

DV: Where did you work at sixteen?

TB: I was a prep cook and a bar back, lugging ice in Vero Beach, Florida at a place called the Village South. It was a steakhouse with twice baked potatoes and creamed spinach. We wore tuxedos. It was super old school. People smoked cigarettes in the kitchen. Then I worked at the Tiki Bar down in the marina. We had frozen rum runners, blackened fish sandwiches, and conch chowder. It was everybody’s favorite restaurant. Each of those places I started as a busboy and eventually became a cook. I was a utility player. When I graduated from high school I had this fine dining experience and this fast casual experience. There was a value in both.

DV: Then were did you go?

TB: On to culinary school, then at high level restaurants. That was about honing the craft and taking ideas to an extreme level. The pressure was stronger. I was 21 and just married with a new son. I was at Pacific Time in Miami Beach. I took on two shifts a day and covered for other guys when they wanted the day off. I wanted the experience and the money.

DV: Was it at that restaurant that you decided not to go back to college?

TB: It was that and the reality of having kids early. I was going to be a chef and that path was clear. Jonathan Eismann was my mentor. He was an entrepreneur and a bada–. The ambassador for Belgium was a fan of Pacific Time and he offered me this job to go to Belgium. Off to Europe and it was all about working in Old World kitchens and doing things that no one does anymore. I was getting into old books and the history of the place. On my days off, I worked at a three star restaurant and a two star restaurant. I hit my goal, and I went to New York to work for Jonathan again. Then 9/11 happened and I came to Dallas.

DV: What brought you to Dallas?

TB: I was recruited here. It was a good paying job and they wanted creative development work done. I helped open Tom Tom Noodle House and Nikita. That’s where I met Jeffers and Zielke [his current business partners, both named Chris] and that whole group. That didn’t work out, so I decided to open my own restaurant. I found this space in Deep Ellum. My wife at the time and another partner, we opened this little place called Standard 2706. It was off the grid and edgy. We closed it a year and a half in. Crime was terrible. Somebody had just gotten shot on Elm Street. We needed to move.

DV: You were done, but not because of the restaurant?

TB: We were doing okay, but it was like “Do we put more money into this?” It was like we were fishing for customers just out of our grasp. Cool people from Neiman Marcus would come all the time, but we moved it to Cedar Springs. It was a prime location, but it didn’t seem to find its legs. I was going through a divorce then closed the business. That’s when I decided to really change my career. The initial spark was this spirit of energy, then honing skills, then about managing people, then being the best at our game. Getting a divorce made me wonder how all this was supposed to work. Was working six days a week how I wanted my life to look? The story sounds good because you’re hard working, or is it better to be there for your kids? I wanted to be able to go see them play ball. That’s more important than what the dining room needs.

DV: Did you find new work in a kitchen?

TB: I went to work for the Mansion under John Tesar. I was there for a year and it was great. We had a good relationship. My job was just about cooking and training.

DV: How did it feel to be part of a crew like that in a monumental restaurant that had transitioned to a new chef and get a five star review?

TB: That was my last day of working there. The last day we got five stars and that was awesome. I didn’t quit for any reason. I went to work for Stephan [Pyles], but I was on a track to get my life in order. I was done being this alpha in the kitchen. That wasn’t an end goal for me. I worked for a year and half with Stephan. I was taking steps, but when I left Stephan I was stumped. I tried my own place and that didn’t work. I didn’t like the corporate chef life. Working for a big juggernaut independent wasn’t working because I was stuck in this spot of having unachievable goals and expectations.

DV: Why was it unachievable?

TB: To be a great restaurant it seemed like you needed to have Riedel stemware and linen napkins in the bathroom, and an elite squad of valet attendants. That’s when I decided to step out of the box. The old me would have just said “Let’s give them what they want” and do it like everyone else.

DV: Is that when you left the restaurant business?

TB: I thought my life needed to be focused on my life and my family. I needed two days off a week. I also needed to be true to myself and do something I’m proud of. Before Smoke opened, my plan was to get out of the restaurant business altogether because I didn’t believe in it.

DV: It seems like you had experienced many versions of it and none were fitting.

TB: That’s right. Parts of them fit, I still had a love for the game, but if you can’t play the game under rules that make sense to you, then you shouldn’t play. I was going to become a food stylist and I was going to make organic soap. I was going to sell soaps at farmers markets. I wanted to be independent, but fall back on the corporate world by doing food styling. While working with Stephan I took a week off and went to Boston for a food styling convention at Boston University. I found some cash and stayed in a dorm on campus. Jeffers called me while I was in Boston. He said “There’s this crazy deal that opened up at the Belmont. They something that’s going to be an amenity to the hotel. It’s in the middle of the nowhere, and it’s probably this building’s last chance at a restaurant. We got in with limited money and the original talk was barbecue, so I said let’s do it. We had nothing to lose. I figured if I take the ship all the way down to the floor and crash, worst case scenario I become a food stylist.

DV: It was the building’s last chance and your last chance in the restaurant business.

TB: It was my Custer’s Last Stand. If it didn’t work, I could walk away clean knowing I had given everything I could to the restaurant industry.

DV: And barbecue was the theme?

TB: As a cook, I wanted to focus on the integrity of homemade and handmade goods. We were all in agreement that it should be some sort of barbecue restaurant, so that’s when I took off. I quit the job with Stephan. On my last day I went with my girlfriend, who is now my wife, and we got in a car and drove east with a book about the Blues and BBQ trail in Mississippi. The plan was to get to Jackson then follow the blues markers for fun. Along the way we’d stop at all these barbecue restaurants. It wasn’t about judging these places. I was about getting some raw spirit of why they got into it. I had a recorder and we asked these people what they’re favorite food memories were. They would get into Jesus and mama and not leaving home messed up because you never know when you need to come back. You start seeing all this being removed from a major market like Dallas and you start to get the chills. You get away from Zagat ratings and star systems and all the nonsense. You’re out in the middle of nowhere and it’s about core values and a circle of commerce. People are buying farm eggs from this chicken guy not because they’re hormone free or anything. It’s because everyone’s been doing it for twenty years and if you stop buying eggs from this guy, his family might starve. That’s when I started thinking about what I wanted in a great restaurant. What I wanted was a spirit of hospitality and a sense of ownership on a customer level. It’s not about me saying I have better brisket than Daniel, and I’m going to everything I can to make sure I have better brisket than Daniel. I’m going to stick it to him. That’s cool if you want to play that game, but it’s not anything that’s going to build community or leave you in a place of…there’s anxiety in just talking about that.

DV: It became about much more than barbecue.

TB: I mean I enjoy barbecue and I enjoy the idea of it, but I enjoy the community of it most. When I went through the Delta I didn’t know about all these people. I didn’t know who John T. Edge was or the about the Southern Foodways Alliance. I met the chef at Delta Bistro in Greenwood. She gave us some recommendations and then told me that I needed to go to Oxford and talk to John T. Edge. I didn’t know he was this significant food writer and major Southern food person. He met with me at Square Books in Oxford. We had coffee and I told him my story and he turned me on to the Southern Foodways Alliance. I went home and back to Smoke. We planted a garden and built this smoker for cold smoking meats. Then I called John T. and asked him if he knew someone to talk to about whole hog. He gave me Ed Mitchell’s phone number, and I went out there [to North Carolina]. Ed took me to his hometown in Wilson where his old restaurant was. They had this mural showing the story of whole hog Carolina barbecue. It shows all the steps and ends at the big house and there’s this really long table with the whole hog. Everybody’s at the table, white and black, and it’s this shared experience. Then we went to the slaughterhouse where they left the skin on the pigs for the barbecue, and then to his restaurant, but when I got back it wasn’t about ripping Ed Mitchell off. The biggest thing I got out of it was the mural and the slaughterhouse. I wouldn’t have gotten that experience without the SFA, and when you look into them it’s all about opening up doors.

DV: It sounds like you got more out of that trip to Mississippi than you ever expected.

TB: There were stories there. I see myself as a chef and a restaurateur, but I also see myself becoming more true to myself, especially as of lately. The cookbook made me understand that a personal need is to be connected and have purpose. The newer stage for me is to become and advocate of American food and the shared table. At Smoke now, we’re more about new firewood cooking. We do barbecue, but that’s not all we do. Opening Smoke became about our core values – honest, genuine, and real. It became the mantra.

DV: Did you go into the book knowing what you wanted to get out of it, or did it change as you got into it?

TB: In the beginning, they tell you want they want it to include, then you have to fight for what you want. I was like “This is my voice and my story, and if I don’t fight for my voice, it’s going to be someone else’s” Everybody wanted it to be all about Texas, but that’s not me. I didn’t want it to be all flags and Lone Stars. I don’t have five year old memories of brisket in San Angelo.

DV: The book was a major success and won a James Beard award. How did you hear about the nomination?

TB: It was crazy. I was sitting in my car in front of Starbucks over here because this was a construction site. That book was the little engine that could.

DV: Usually you’d be watching that list to see the chefs who are nominated.

TB: Yeah, but it was a huge honor, and then there’s the question of “Who am I?” Am I a chef or a writer or whatever?” For me it’s important to have purpose and connection. If I want to ruin the rest of my life working seven days a week and constantly trying to be better than the next guy, then maybe there’s a chance I could become a James Beard award winning southwestern chef. Or maybe, if I continue the path I’m going, maybe that’ll show and I become a James Beard award winning chef. Who knows, but with the book it was a crazy heartfelt project. I didn’t want to leave anything on the table. I had one chance at a great book. I went to press broke on it, but proud that our spirit was in there. I wanted to break this all-barbecue mold.

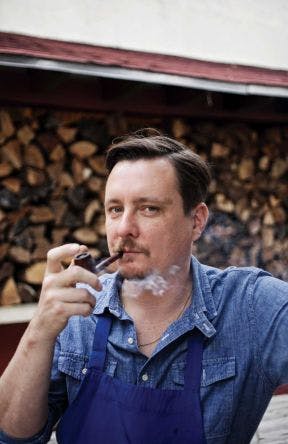

DV: And smoking the pipe at the end?

TB: They tell us we had two pages left. I had run out of stuff, so the final how-to was how to smoke a pipe. It was stupid, and they loved it. It so naturally filed in there. It helped cut the edge off the barbecue thing. I wanted it to be about firewood cooking and working with your hands, making sausages and what I consider exceptional biscuits. I try to cook in a nostalgic way, but represent the food in a new way.

DV: It’s like when you opened Smoke you could order meat by the pound on the scantron sheets, but then you also had this whole other menu.

TB: Yeah. Now it’s like are we a barbecue restaurant? Sometimes. Then we had a vegetarian menu, a regular menu, then the barbecue scantron. That was us honoring meat by the pound, but also having fun with it. You know what? We’re not going to be Snow’s. We’re a full service restaurant with ambitions of having a great experience. It’s like being at Chicken Scratch on the first day of spring when it’s 75 degrees outside and people are out there and there’s a band. Everybody’s happy. Kids are running around and people are drinking. It’s an experience that you can’t get anywhere else in town, and it’s rad. To be able to do that in between a condemned hotel and a trailer park…now we’ve got hotels going up around us.

DV: Back to Mississippi. I’m guessing you didn’t find much brisket there during your trip. How did you find the inspiration for the brisket at Smoke?

TB: I just dove into it. I was more into doing it than impressing people.

DV: Did you just go buy this big Bewley smoker and just start throwing stuff in there?

TB: That’s pretty much what happened. What else are you going to do?

DV: You could talk to some of the barbecue people around who have been doing it.

TB: Okay, but we’re not that salt & pepper only stuff. I wanted to do our version of it. If something is working for us with the brisket, then we have that day’s brisket. It’s like the people on the quest to find the pink butcher paper that Aaron Franklin uses, it’s like just do it or don’t. It’s not the holy grail. Nobody is lining up around the block because of the butcher paper. Who f—ing cares? It’s a sandwich. Have a damn sandwich. I’m proud of our sandwiches, but I’m more proud that we make everything on that plate than being in the Top 50 best brisket places in Texas.

DV: There are no shortcuts on the plate.

TB: Yeah. The hearth thing we have is wildly primitive. We have guys who come in here and thy don’t know how to do any of this stuff because it’s off grid. The sauté station here is taking a pan and putting it in the coals. It’s like cooking outdoors on a campfire.

DV: How may of your cooks came here because they could cook in a different way here?

TB: Most of them.

DV: So, is the hearth here the fruition of you being in the business of being you?

TB: Today it is. It’s something we didn’t have the room for at Smoke Dallas. But we have some stuff down there that’s not replicatable here. This isn’t something I see as a newer and better version. It’s probably a little cleaner and more stylish. I don’t know which one’s better.

DV: As far as location, this seems like the other end of the spectrum. You’re next door to a TGIFriday’s at Preston and Park in Plano.

TB: For sure. That was on purpose. It’s great being called a pioneer, but pioneers had rough, hard lives. Westward expansion…people died on their way out to California. That’s where we started, but we’re not in the business of being pioneers. This was meant to recreate the spirit of Smoke. It’s not about coming up here and telling them how to eat like downtown Dallas people. Nobody wants to hear that s—.

DV: But they do want to hear how we eat in other countries, and you recently got the chance to go share your cooking style with folks in Kyrgyzstan as a culinary ambassador. How did that come about?

TB: The U.S. Chef’s Corps is made up of 100 chefs across the country and we all represent a region. After winning the Beard award I got my name onto someone’s desk. It opened up the opportunity to go out of the country and share our culture. I went and lectured at a university. We went to their market and it was phenomenal. We made a menu, and I brought chile peppers and pepper seeds. We did a dry rub and grilled a steak. We did melon with charred tomatoes. They thought I overseasoned everything, and they thought I was nuts when I added honey to the salad. Honey is only used for medicine there. Then they ate it and thought it was great.

DV: They were vocal about this watching you cook?

TB: They thought I was nuts. They’re like “This guy is using a whole cup of barbecue spices on this one steak and grilling it. This is ridiculous.” Then they were showing me how to cook horse meat. That was a great boundary cross. Their view of me was all about McDonald’s and heavy branding like Nike and just consumerism. Then there’s also this mystical place called America that has power, but there’s no vision of us being people. We go to this village and meet the village wolf hunter. These people are bada–. They hunt with falcons and they’re all incredible horsemen. We’re in this village and they bring a sheep out and kill it. They simmer it in this huge cast iron pot over the coals, then they serve it with this incredible native rice dish called plov. Then we sat at a table where the seating is based on position. The most honorable is the oldest woman. She gets the first choice for the cut of meat. Then there’s me because I was the guest, and I got the head. As an American it’s like “This isn’t what we would choose as the best cut.” But I didn’t say that, I just ate it. The eye was something that they carved out and I shared it with another guy. It just lowered he guard of everyone there, and the way to do that is to eat and share. It’s like that Ed Mitchell mural.

DV: Did any part of you find it ironic that a guy not comfortable writing his book as a Texas book became the culinary diplomat showing Texas cuisine to other countries?

TB: I think our story gets pinned in by everybody’s view of Texas. I’m not going to talk about the Alamo. The Alamo is rad, but it’s not about this story. I think Texas barbecue has gotten collapsed and collapsed and collapsed all the way down to Mrs. Baird’s white bread, brisket, dill pickles, raw onions, and no sauce.

DV: There is certainly more to it than just Central Texas barbecue.

TB: Going down with the Titanic over no sauce? That’s not my game. That’s too much work.