Owner: Mikeska Brands Texas Bar-B-Q; Founded 2008

Owner: Mikeska Brands Texas Bar-B-Q; Founded 2008

Age: 56

Smoker: Brick Smokehouse

Wood: Oak wood with oak and hickory sawdust

Tim Mikeska has had enough with running restaurants. He’s traded it in for the wholesale sausage business, and now his family’s Czech sausage recipe can be enjoyed in Texas, New York, Connecticut, and all over Chicago.

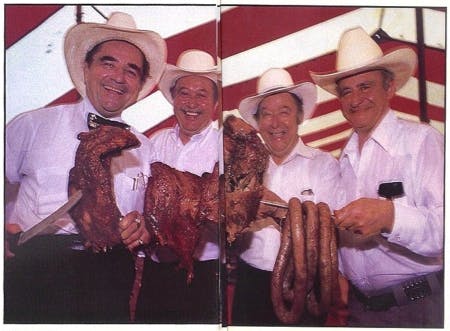

He comes from a long line of butchers and barbecue men. If you’ve traveled the highways of Texas, then you’ve probably seen at least one billboard for one of his uncles’s barbecue restaurants. There’s Clem Mikeska’s in Temple, Mikeska’s in El Campo, and Jerry Mikeska’s in Columbus. In 1986, Texas Monthly even called them the “first family of Texas barbecue.”

For years Tim ran Rudy Mikeska’s Barbecue, a restaurant built by his father in 1971. Before it closed in 2009, it was located in Taylor just across the street from Louie Mueller Barbecue. Tim and I met inside Louie Mueller to talk and share a few slices of brisket. Sadly, they were already sold out of sausage.

Tim Mikeska: Everybody wants to be a sausage maker. Everybody. They make it, and then a month later they say “that was some hard s***. I don’t wanna make it again.”

Daniel Vaughn: What is your advice for someone who wants to be a sausage maker?

TM: You just go right ahead. Good luck with it. And you know what—another thing: I looked at my Facebook and Freedmen’s has this bacon cheeseburger sausage. I just saw a post for it. People need to quit this. Was it Smokey Denmark that had the macaroni and cheese sausage with chorizo? Stop that.

DV: It was good. What do you have against stuffing other foods into casings?

TM: It complicates my life when people see it at an uninspected facility and they want us to do it in an inspected facility. They say “hey, can you?” and I go “no.” I mean I made a brisket boudin for a guy in Louisiana. It was really, really good. I made the demos because I can make demos at the ranch without having to go through the USDA. Then I apply to the USDA and I have a problem with rice, then I had a problem with having to take the smoked cold brisket and mixing it with hot boiled liver. I got about 11 pages [of comments] from the USDA. That’s my problem. They see something made and they think it can be made commercially and it just can’t.

DV: So your complaint is that people come up with ideas that are hard for you to replicate? What’s wrong with that?

TM: Yes. And here’s the other thing I did the other day to my own self. I took some shrimp and crawfish and smoked them, the other half I made into an etouffee. I was going to stuff that into the casing and I thought this was going to be really, really good. I got my stuffer ready, and a tried some. I said “this is really good.” Then about an hour later, there was nothing to stuff. I ate all of it.

DV: When did your family start making barbecue?

TM: We’re the typical, Czech family. My great-grandparents immigrated here in 1880. Every family back then had some sort of skill set; it was either a blacksmith or whatever. Ours were butchers. My great grandfather and my dad, Rudy, were butchers. My grandfather, John Mikeska, was a farmer south of Taylor. They didn’t have any money. They were butchers and at the turn of the century when he started having sons, he really didn’t think of it as having kids he thought of it as employment opportunities – it was a built-in workforce. So, when my uncles, the six brothers, were very young they went around to the other farms and ranches and they ran a beef club. All of these Mikeska boys were butchers as kids. They didn’t have any money and my grandfather said that you’ll never be rich doing this, but you’ll never hungry because they had that skill set. In 1936, when my father was only 16 years old he was the meat market manager over here at Spiegel Grocery Store, right down on Main Street. He ran the shop. He’d go to school, come back, butcher, work all night. Typically like they did in all the ‘30s and ‘40s, they took all the meat that they couldn’t sell during the week, they’d either make it into sausage or they would take the whole pieces and they would go down about three doors down where there was a pit barbecue joint. Later owned by Novosad, and then later owned by my dad. But this was before that. It was kind of a beer joint, walk up place that had a barbecue pit. So they cooked it there on Fridays and Saturdays. Then World War II comes around. My dad’s three other brothers were already in the war, they were already overseas. Fortunately for my dad, he had a skill set—he was a butcher. So when they drafted him, they asked him “do you have a job?” and he said “yeah, I’m a butcher in a store” and so the U.S. Army Air Corps sent him to Camp Pinedale as a meat and dairy inspector. Just like you would see the USDA now, he was a United States Army Air Corps meat and dairy inspector. He used to say “you know, I may not have fought the Germans or the Japanese but I fought the hell out of the germ warfare.” The reason he took it seriously was because he had three other brothers in combat in France and Europe, and he didn’t know where the food that he was preparing was going. He wasn’t sure if his own brothers would be eating. During that time, on his days off, he went to work and my mother went to work for a grocery store at Fresno, California. He got to be very popular on his days off by butchering meat and making sausage, because they hadn’t seen this before in Fresno, California. They hadn’t bought Czech sausage until 1942 and they were like “what is this?” When the war was over, they offered him a job. He said no and hitchhiked back to Taylor, Texas.

DV: What about your mother’s side of the family?

TM: My mother grew up like me, working in a restaurant. In 1928 when my mother was six years-old, they were hired as managers for the Taylor Country Club. My grandmother, Bessy Marshall, worked the kitchen and my grandfather, Dan Marshall, was the golf pro. My mom and dad were married before the war. When my dad came back, my grandparents gave him a job at the Taylor Country Club in 1946. It was there that he became very famous for his steaks and restaurant business. They still did barbecue but he was already married.

DV: What was he cooking at the country club?

TM: Steaks, seafood, and catering events. He became very famous for his steaks And then sometime in the early to mid ‘50s, Novosad had two main barbecue joints; one on Main and one on South Main in Taylor. My dad bought them both. So he managed the Taylor Country Club and he had two barbecue joints. Dad then expanded and bought two more on Fourth Street. So, my dad at one time had four barbecue pits in Taylor, one in Temple, and was running the Taylor Country Club. Then in 1963 he bought the famous L&M Café in Georgetown, which was the busiest restaurant in the county. It was a 24 hour restaurant.

DV: Wow. That seems crazy to me that he would buy two barbecue joints in Taylor that were right on the other end of town—I would close one of them.

TM: Yeah. For the one on Fourth Street, he said “you know, I’m gonna make this a nicer place.” He bought the lot next to it and built a brick building there in 1963. It was air conditioned, just a beautiful building. Right next door was the original barbecue pit. He opened the new place and he intended for the one next to it, the original one, to just stay there. People could go anywhere they wanted, there was no rules. All the people just kept going into the old one. They wouldn’t go into the air-conditioned building. So he stayed open for a couple of years and he closed and just used it for storage.

DV: Are there pits still in the back?

TM: It just changed hands last year. The guy that bought it was like “you know there are still barbecue stacks going to the ceiling? And there’s still brick pits?” And I said “yes. What are you gonna do with them? “

DV: This was on Fourth Street you said?

TM: Yeah, two blocks up.

DV: So then what happened to all these past locations?

TM: Sometime around 1970/71, our catering business started getting so big that there was no way we could do the jobs that we needed to do and cook the amount of food that we needed on the forty square foot brick pit. My dad’s catering business exploded.

DV: All the catering was run out of which location?

TM: On Main Street right by Vencil’s. It was just getting too much and he was having to cook round the clock all of the time. This old building became available in 1971, he bought it in 1972 and then he just shut the other places down and combined everything. The one in Temple was sold to one of my uncles, Louie Mikeska.

TM: So, how many of your uncles got into the barbecue business?

DV: All six of them. Uncle Mike is in Smithville, Uncle Louie was in Temple, Uncle Clem was in Temple, Uncle Maurice is in El Campo, Uncle Jerry in Columbus and my dad in Taylor. Then, in 1972 he combined everything in this building. He’d already sold the café in Georgetown, he combined everything over here and then he made this into a commercial catering facility.

DV: Were all the brothers together in this catering company?

TM: No. Everybody was individually. I love my family and we’re very close, but we don’t do anything together unless we have to do a big job together. And you can say what you want about the Mikeska family’s resistance to change, but if you were to have a list of the top 50 caterers for barbecue, we would be pretty high up on that list.

DV: How did Rudy build that business up? Who were some of his first clients?

TM: It goes back so far into the country club days. All the big politicians, Taylor was the hub of a lot of political things back in the ‘30s and ‘40s and ‘50s. It was the biggest city in the county. A lot of famous lawyers and politicians were here. In 1970 and ‘71 we did 10 jobs a weekend and serve 5,000 people. It continued to grow because there wasn’t a lot of people catering back then. Then we started doing the governor’s inaugurations. We did both of Bill Clements’s inaugurations. When we were able to pull off 10,000 people all by ourselves, it just continued to grow and grow to the point where we were catering for 10 or 12,000 people a week.

DV: When I’ve seen photos of Mikeska barbecues, they look like big shows, as well. These days, it’s like you show up to a big catering gig with barbecue and it’s all cut up in trays. You just walk through a line and pick it up.

TM: My dad was a showman, there’s no doubt. They cut it all right there. Brisket, chicken, sausage—we cut sausage up into two or three pieces, trying to stretch it out. We didn’t given them a whole link. It was easier for me to cater for 5,000 people than it was for me to do 50 people in a building in downtown Austin. That’s when you have a problem. But when you have 5,000 people, my head just clicks that way. The most that I ever personally catered after my dad died was 13,500 people. That was at Williamson County Sesquicentennial in 1998. I cooked 1,200 brisket in 24 hours, along with 3,000 links of sausage.

DV: Let’s go back. What were your first memories of your dad’s barbecue place?

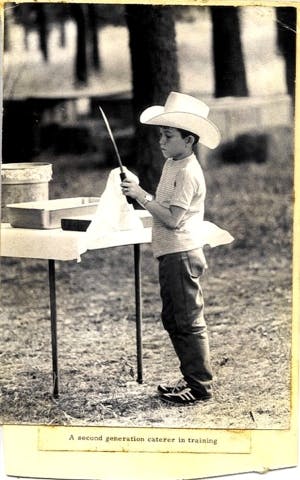

TM: I had the best childhood that any kid could ever have. Let me tell you how long I’ve been in the business. In February 13, 1960, it was a Saturday, and my mother was catering a Valentine’s party. She went into labor there at the country club. I was born the next day on February 14. Three days later they bring me back to Taylor Country Club and put me in a cardboard meat box with bar towels and told the bartender, “watch him.” I grew up, riding the dumbwaiter as a toddler. I was always around food. The first memory I believe I have is going in to the old pit room over here and watching them cleaver-chop lamb ribs. At around seven years-old, my father taught me how to debone a chicken wing. I started cutting meat when I was about seven. In the old days, over here at the old pit, brisket didn’t come bagged. They came on the whole plate. We would have to peel them, that’s take the brisket off the lower five-bone plate.

DV: Brisket came bones and all still attached to the forequarter?

TM: It was the lower chuck. The skin was off, but it was whole. We didn’t cook the ribs. Back then we boned out the ribs for sausage and served the brisket. Now they’re making a fortune out of these ribs.

DV: The short ribs?

TM: Yeah! They didn’t want them back then. When I was seven years-old was my awakening in the business, because he finally let me do stuff. My dad showed me how to make sausage. I wasn’t tall enough to reach the table, so he would stack up these Coke boxes and I would get up there and link sausage. I was really good at it, but I didn’t handle the stuffer or the grinder because that stuff could kill you in many different ways. It wasn’t until I was 16 that he actually trusted me with the recipe.

DV: It sounds like your earlier memories were much more about the butchery part than it was the barbecue.

TM: Yes that’s right. I never even got close to the actual working the brisket to put it on the pit until I was probably 13 or 14 years-old. Before that it was cutting and making sausage.

DV: As for as the menu at the old location…

TM: Brisket, sausage, lamb ribs and pork ribs. That’s it.

DV: How early on was the brisket on the menu?

TM: I remember from the mid ‘60’s there was always brisket. Lamb ribs was the big seller. I still love it. Let me tell you, I used to not be able to ride my bike in here because my hands had so much grease on them from the lamb breast. Another memory is my dad selling sausage to about four different places in The Line. It was an area south of the tracks that had barbecue joints, bars, and blues clubs. They’d run out usually on Friday and Saturday nights so my dad and I would go deliver more sausage to them. I would go into these places that had dirt and pea gravel floors. The smell that you walked into, all the stuff burning, the cigars smoke and lots of other stuff was burning. My dad would have this big butcher paper wrapped load of sausage. When he came in the door they’d say “Let Mr. Rudy in! The sausage man is here.” He would go in and I would go and shoot dice and pitch pennies. And The jukebox would have Motown on it. It would have the Shylights or Marvin Gaye or the Temptations. He wasn’t in there very long, so he had to drag me out. I loved that atmosphere. I loved the fact that my dad was selling sausage, and it’s almost come full circle. This last year I was at the Kentucky BBQ Festival. I was the emcee. There were thousands of people there and I’m trying to get back to the stage. I was running late, and a guy comes up and a woman comes up, and they said, ”Make way! Get out of the way! Here comes the sausage man!” And I froze in my tracks. This feeling of peace came over me. I made it.

DV: When your dad made that sausage was it always one recipe?

TM: Yeah. Well, it was pretty much the same. The first hot gut was made with lean bull rounds, beef navel plates, which are very fat, tallow, and tripe. It also had to have a lot of binders in it back then. When you put that much stuff in sausage you have to have something to keep it all together, and we used bull flour.

DV: But your recipe is a pork sausage now.

TM: The beer joints my dad was selling sausage to kept telling him that if the sausage was hotter, they could sell more beer, so he would up the spices on the hot guts. The clubs were gone by the 1970’s, and our catering business had gotten so big. So many people wanted sausage that it was not conducive to have a very hot spicy hot gut when you’re catering the Governor of Texas. You know what I mean? Grease is running down somebody’s chin…

DV: That sounds perfect to me.

TM: Apparently they didn’t like it that much, so we started to calm it down. We took out the tripe and added pork trim. You had to adjust the spices when you adjusted the fat. It’s the same spices, but you have to tweak the amount. Then about 1980 we started going straight pork using pork trim. A few years later they made a mistake on our delivery. I opened up the boxes and it was nothing but pork butts. We didn’t cook pork butts, so they sent it instead of the pork trim for the sausage. My dad said, “Go ahead and make it.” And I said, “Make it out of this?” He goes, “Yeah, you’ve got no choice.” So I made the sausage with the whole shoulder muscle. I hung it in the pit to smoke. When I opened the pit door up I didn’t see it dripping. When we had beef hot guts in there or trim sausage it was raining fat, but it was not dripping. It was getting thick and full. And I said, “I can’t wait to eat this.” And when it came out of that smoker, it was unbelievable. Dad had gone home to rest. I always made sausage in the afternoons, and he would go home and rest and come back. And I said, “Dad, you gotta try this.” He goes, “Well, we’re gonna have to go up on sausage” becaue we were going to use the whole muscles.

DV: No more pork trimmings?

TM: No more pork trimmings.

DV: So you’re making the same sausage today that you made with that pork butt?

TM: Yes. People see this label and they see it’s got pork, water, spices—“Where’s the rest of it?” I say, “That’s it.” And they say, “Well, this is crazy!” If you have to have a chemistry degree to read a sausage label, then get some different sausage.

DV: You have sodium nitrite in there too, right?

TM: I have to have nitrite. The USDA requires that, but I don’t consider that a filler.

DV: What is it about the recipe that makes it a Czech sausage?

TM: About five years ago, I was going through some of my dad’s stuff in the warehouse, and I found a box. And in this box was something about two feet long and it was wrapped in butcher paper and tied in butcher string. I opened it up, and in it was two Foster Brothers’ butcher knives, all carbon steel butcher knives. And I was able to trace those to between 1894 and 1905. With those knives was a paper. On the paper it had the word “otec.” Otec is the Czech word for father and below it was a recipe. I recognized it immediately because it was the recipe we had for sausage. It was a little different in quantities, but it was the same recipe. My father would have not have called his father otec. With this being from the early 1900’s that had to be my grandfather talking about his father. It dawned on me how old this recipe was.

DV: Was it the beef sausage recipe, or the one you’re making now with pork?

TM: It could actually be with beef or pork. They actually did fifty-fifty. The most important thing that I learned from my dad when it comes to making sausage is never skim on the quality of black pepper. There are a lot of different types of black pepper, but he insisted on buying tellicherry pepper. It’s expensive. Up to twenty, twenty-five dollars a pound now. Back then, it was three times higher than any black pepper, and it would come in fifty-gallon drums. That’s how much pepper we were using. He said that was the key to a great flavorful sausage—the black pepper. Yes, it’s got red pepper, garlic, and salt, but the quality of the black pepper is something you never skimp on.

DV: Your dad had this barbecue place, you worked with him there, so at what point did you take it over?

TM: Dad told me one day, “Look, I need you here all the time.” I started full time in 1985. I knew every aspect of the business. He died in August of 1989. He had cancer for about a year. My sister and I took over in August of 1989. I realized that I’d spent my entire life for this moment, getting ready to take over. I missed him so bad that it was very difficult for me. Then in 2003, I was going for a routine checkup, and I was diagnosed with renal cancer. I ended up having a two and a half pound tumor in my right kidney.

DV: How long did it take you to recover?

TM: I was sick for about a year and a half with the other issues that went with that. It was very stressful. I decided, that’s it, I’ve had enough with the restaurant business. I’m going to start this whole Mikeska Brand Wholesale Food Company, and that’s how it started.

DV: And the Mikeska Brand Wholesale Food Company, that’s all sausage, right?

TM: Yes, only sausage. I was already under USDA inspection by then. I was in the restaurant one day, and Barry Sorkin came in. He had this plan for a barbecue joint in Chicago. I said, “Are you out of your mind? What do you want this kind of heartache for?” But he had a great business plan and a great business model. And I said, “If you’ve got this kind of help and you’ve got this kind of determination, go for it.” He went back to Chicago to open Smoque, but he never talked to me about sausage. About four months after he opened he came back, his time with Craig Goldwyn, aka Meathead, and Andrew Bloom from Wichita Packing in Chicago. They were on a sausage quest. I got some sausage for him, and they were all pow-wowing in a circle. He came over, and he says, “This is the sausage I want for my restaurant.” And I said, “Great! I just happen to be USDA Certified. When can I ship you the first case?”

DV: Was Smoque your first big customer?

TM: He was my first customer. Period. We’re close. I get emotional when I talk about Barry because he’s such a good guy. And he has this passion for what he does. And he had this dream of bringing this regional food together like this, and yet, he did it in Chicago. And then there’s been so many people who have spun off of him, this idea and concept. But he’s been the most successful.

DV: But he’s not your only business in Chicago now, right?

TM: No. It took off pretty quick. We ship sausage by the truckload to Chicago. A lot of sausage goes to Chicago from Taylor, Texas. It goes out from there to the metro area to Wisconsin all the way into New York and into Connecticut. I was in line at Smoque in Chicago talking to everybody and this guy is writing all this down. He’s a reporter and he says, “You’re like Abe Froman now.” You know, the guy from that movie Ferris Bueller’s Day Off – the “Sausage King of Chicago.” We do sell a lot to folks like Gary Wiviott with Barn and Company and Jared Leonard at Rub’s Backcountry Smokehouse.

DV: You’re also selling to some Texas barbecue places as well.

TM: Yes. Pappa Charlie’s Barbeque in Houston and I’m headed up to Riverport Barbecue in Jefferson soon.

DV: You have all these distributors but I wanted to ask you about a particular vehicle that you use to deliver sausage.

TM: Yes. I’m on my third Hot Gut One. I’m a pilot. I’ve been flying for 30 something years. Flying originally was something that I did to relax. It didn’t become a vehicle to deliver sausage until I started Mikeska Brands. I have the ability to go pretty quick. Being in a company plane does make my life a little bit easier.

DV: As someone from a barbecue family with a long history, what are your thoughts on the new barbecue movement in Texas, especially the Austin area?

TM: When you talk about my family and their barbecue, none of our food is the same. They have been a little resistant to change. Anybody that has been in the business for 50 or 60 years, they’re having difficulty changing. This retro/hipster movement in barbecue has caused a totally different epiphany of barbecue in Texas. The reason I call it retro is when I sat down at Aaron’s [of Austin’s Franklin Barbecue] trailer all those years ago and ate that brisket, it was the same brisket we did in the 60’s. It was what I call full-term brisket. In the catering business, you can’t take it full-term. If you want to put a brisket in this retro/hipster movement now in a meat can and fly it to New York, by the time you got there and unloaded your airplane, you could strain it through a towel. So, when I ate that brisket at that little trailer he had, I was like “Well this is really good, but we were doing this in the 60s.” I walked over and went to meet the cook and he was just starting out. He was cooking about four or five, and I thought to myself “If this stuff takes off, he’s going to have to cook a little bit more than this.” Now I tell everybody that’s getting into the business to embrace it. Go out there and taste the Texas Monthly Top 50 and start wherever you want and see what’s out there. A lot of them don’t want to do that. My dad always said “the minute you quit learning, it’s time to go.” I’ve learned some good things and some bad things about by visiting some of these places.

DV: Do you have a favorite?

TM: That’s in business right now? I do, but I’m not going to say who it is. I will say this. North of the Red River. It would have to be the brisket at Smoque. For overall food as a foodie, it would have to be Jared Leonard at Rub’s Backcountry Smokehouse for all the other things he’s doing with it.

DV: Where is your sausage made?

TM: It’s made right down the street over here at the plant. I’ve got a long history with Taylor Meat Company. We have been with them for 60 years. I still make sausage, don’t get me wrong. At my cousin’s ranch we make a lot of sausage, especially exotic sausages for customers. I’ll tell you a story about linking. In 1981, I was making sausage over here at the restaurant. This man rolls in with this big hunk of machinery. It was a linking machine. I’m going “what’s he doing here?” Well dad came in and said “Come in and set it up.” It hurt a little bit because that was my job. Anyway, he put the sausage in there and it started linking and just spitting it out. So I started linking beside it by hand, and I beat the machine. Well the guy goes “but ours is going to be more accurate.” We were doing four to a pound, so dad took four random links that were mine and four out of the machine and went and weighed them. He said “my son’s was 1.03 lbs and yours was 1.06 lbs. He was faster and more accurate, so you can take your $17,000 machine and see ya.” This guy looks at me and he goes “Thanks a lot, kid.” He packs it up, and he leaves. I felt like John Henry. I start linking again and all of the sudden it dawned on me. What the hell did I just do?

DV: You could have just made your job a whole lot easier.

TM: I would have never had to link another sausage again. It was too late, but that was a proud moment.

DV: I’m guessing there’s a linking machine at Taylor Meat Company now.

TM: Yeah, there’s a linking machine. The times of me linking sausage are gone.

- More About:

- Sausage