Barbecue in the Texas Panhandle has struggled for a foothold in statewide prominence, and that’s not entirely because of its far-flung locale. The area is a relative newcomer to Texas barbecue history. Amarillo’s founding in 1897, after all, was a year after Southside Market opened in Elgin. The oldest barbecue joints in the area opened in the fifties, which explains why Texas barbecue lore rarely mentions the Panhandle. Still, the region has produced one of the best barbecue cooks you’ve never heard of. Back before Aaron Franklin, before Sonny Bryan, heck, even before Walter Jetton, there was a man they called “The Barbecue King.”

At the age of 77, John Snider estimated he’d cooked over 4,000 whole steers—his specialty. He fed tens of thousands across the country, including Presidents Franklin D. Roosevelt, Harry Truman, and LBJ. He was cheered by Panhandle ranchers in 1937 as a “master of the art of barbecue,” according to The Canadian Record, and in 1936 the Palacios Beacon said he was “reputed the best barbecue artist in Texas.”

Snider didn’t come from a line of pitmasters. He was born John Renison Aldridge in Collin County, but at the age of thirteen he moved to the Panhandle town of Tascosa with his mother, Mary, and adoptive father, George M. Snider. By seventeen he went by John Snider and had taken a job at the U Bar V Ranch, where one of his duties was the gruesome task of burying the same hanged horse rustler over and over again. According to his 1947 biography in The Junior Historian, “Every spring the winds changed and blew the body out of the sands, and John and the other boys would rebury it.”

Snider spent some time chasing steers on the cattle trails headed to northern markets, but preferred life on the ranch until he moved to Amarillo in 1902, shortly after the city was founded. His barbecue career quickly flourished in Amarillo, as he told the Fort Worth Star-Telegram. Snider said he was “called to pinch-hit for a cook and barbecued a whole animal”—his first. It was 1903. He told a more colorful story of his start in barbecue to The Washington Post* in 1932:

Well, when I was a youngster I used to go lots of barbecues. Before the barbecue had finished I was usually the only sober man left on the lot, and, naturally had to finish it up. This happened so many times that I finally just decided to become a ‘barbecuer.’

Despite his eventual fame, barbecue was just a side job for Snider. Minus a short stint as an insurance salesman in Fort Worth in the twenties, Snider was a West Texas lawman. He joined the Amarillo police force in 1905, eventually working his way up to city marshal. By 1930, after a brief stint in Fort Worth, he was back in Amarillo for good as a level-headed city detective (in 32 years on the force, he never fired his pistol), but the big barbecues never ceased. In 1926, the job was “seventy beeves and as many muttons,” in Fort Worth for the West Texas Chamber of Commerce’s gathering of 6,000 members. Snider fed 2,000 in Wayside in 1931. The biggest of his career was in 1924 when 15,000 gathered at the Henry Hardin Ranch, but they only had food for 12,000. Even still, the biggest challenge of the day was getting the cars back out of the deep canyon that night. As people piled into in their Model T’s their gravity-fed carburetors quit working and most stalled out on the steep gravel road. Others tried another steeper route backwards, but they also got stuck. Reports from the Amarillo News-Globe don’t say how everyone eventually got out, but Snider learned a lesson too that night: he was never again short on barbecue.

Cooking whole steers over wood coals made Snider famous, but another of his side dishes lives on in Panhandle barbecue joints today. In 1922, he began serving stewed apricots with his barbecue. Along with his secret-recipe mop sauce, it became something of a signature. It’s the first mention of stewed apricots with barbecue I have found, and serves as the only reasonable explanation that joints like Sutphen’s in Borger (originally opened in Phillips in 1950) and Dyer’s Bar-B-Que (1967) in Pampa and Amarillo serve it with their barbecue today.

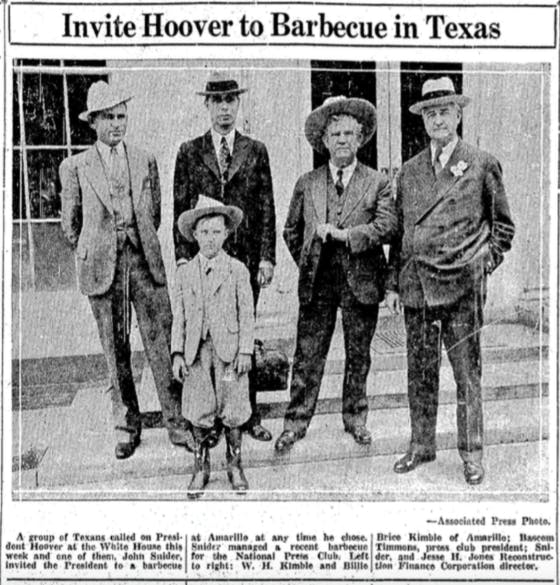

Snider brought the apricots along with 30 steers with him to Washington, D. C. in 1932. An Amarillo journalist, Bascom Timmons, had become the president of the National Press Club and invited Snider to cook Texas barbecue along the banks of Chesapeake Bay for the club’s annual party. Snider drove from Tuesday to Sunday in a “motorized wagon” with the men he referred to as his “barbecue sergeants” and his spitz dog Chico. (Supposedly, a Movietone newsreel team filmed the 1,850 mile journey, but I haven’t tracked down the footage.) Along with the beef and apricots, they served pinto beans, potatoes, onions, pickles, and coffee.

It was “one of the greatest feasts in the history of the National Press Club,” according to The Washington Post*. The reporter marveled that “the animals were cooked in immense pits over which Snider kept watch 22 hours without rest.” The barbecue impressed the lawmakers who attended so much that Snider was invited to the U.S. House of Representatives to be recognized. He received a standing ovation. Snider was later invited to the Egyptian Embassy by the country’s foreign minister Sesostris Sidarous Pasha to share some barbecue secrets. “The minister was much interested in Mr. Snider’s method of barbecuing,” per The Washington Post.

To much celebration, Timmons invited Snider back to Washington in 1938 for another National Press Club event. The Cisco Daily News (who, like a few others, misspelled his name as Snyder) got downright sentimental, calling him “the last of the old chuck wagon cooks.” President Franklin D. Roosevelt was the guest of honor, and the menu included “twenty grass fed steers” for the 2,500 guests. Texas Senator Tom Connally also attended, and got a bite straight from the pitmaster’s hands, as shown in the photo at the top.

It took until 1947 for New Yorkers to take note of Snider’s particular brand of Texas barbecue, The New York Herald Tribune sent legendary food writer Clementine Paddleford** to New Mexico to watch Snider prepare 650 pounds of beef and mutton, barely an appetizer by Snider’s normal standards. Paddleford noted an unusual side item on the menu. “Salad was made by a local restaurant, the company’s idea, and to John’s disgust.” There’s no place for salad on the chuckwagon.

Paddleford’s descriptions of the preparation paint a detailed picture of Snider’s method. She wrote that Snider and his team had set up up a pit with metal sides and grate on top. Space was left between the sides and the grate to shovel coals in during the cook. A feeder fire is set up next to it. They used mesquite, “but to John’s mind piñon would be ten times better.” They lit the fire at 5 in the morning, and the first meat went on an hour and a half later. The meat was covered by a canvass during cooking, and was turned by a man with white gloves. The barbecue was served on high tables that diners stood around, and “there was a spoonful of dried apricot to a serving, the fruit cooked down to a jam-like consistency.”

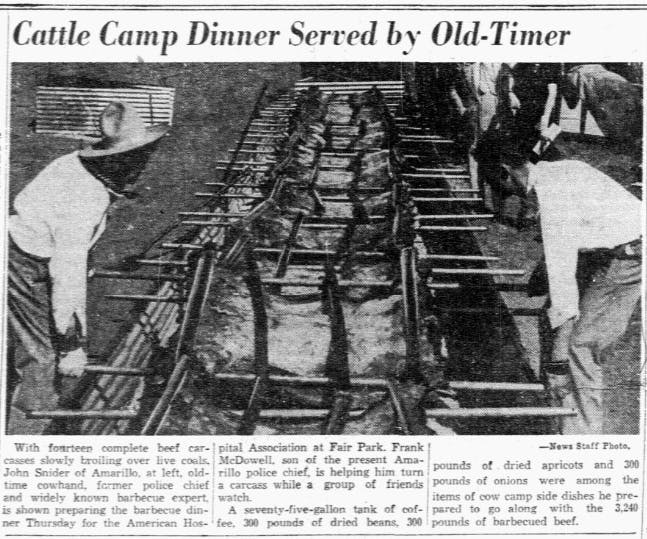

That day, the beef carcasses were cut into large chunks, but Snider usually cooked the entire animal. He preferred yearlings—somewhere between what we consider veal and a full-grown steer—for their smaller size. Cook time was between 15 and 24 hours, during which time the beef was mopped with Snider’s secret sauce. The only fuel was hot coals. “No live fire is allowed under the meat at any time,” the Dallas Morning News noted when a reporter watched him cook 14 steers in Fair Park in 1938.

Snider’s second wife, Ida, may have been on his crew in Dallas. In the 1940 census, “barbecue cook” was her denoted profession. In 1946, she passed away before his next big trip. The National Press Club asked Snider back for one last hurrah in 1950, when the pitmaster was 77. He had retired from law enforcement five years prior, but still looked the part in a nutria Stetson he’d owned for half a century. Whole beef carcasses were cooked over oak coals (they couldn’t find mesquite), enough to feed 3,000 including Sam Rayburn, John Connally, and LBJ.

Snider was 84 on his last cook I could find a mention of. It was a barbecue in Amarillo in 1957 that got only a few lines in The Tulia Herald. He passed away six years later. One obituary barely mentioned his barbecue skills, favoring the story of a deceased Panhandle lawman. A writer for his hometown Amarillo Globe-Times, someone who had probably eaten his barbecue, offered fond memories of Snider’s beef and barbecue sauce, and of course those apricot preserves. He may have been a marshal with a badge and a gun, but it was a shovel and a mop that made John Snider a king.

* Thanks to David Fahrenthold and Alice Crites at The Washington Post for providing these archive articles.

** Thanks to the Special Collections department at Kansas State University for providing the article from their Clementine Paddleford collection.