Walter Jetton, the self-appointed “King of Barbecue” in the fifties and sixties, was a restaurateur and a mega-caterer. He cooked for presidents and heads of state, and his most significant claim to fame (a good one, at that) was being LBJ’s pitmaster of choice. This clout gave him a prominent platform to serve as an ambassador for Texas barbecue, a role he took seriously as he spread the word of his favorite cooking style across the country.

Jetton’s rise to national fame was improbable. His father abandoned his family when he was two, and Jetton was primarily raised by his grandparents in Fort Worth. He dropped out of school at 13 to bring in money apprenticing under butcher Frank Williams. At 31, Jetton leased and operated the meat market before purchasing it outright seven years later.

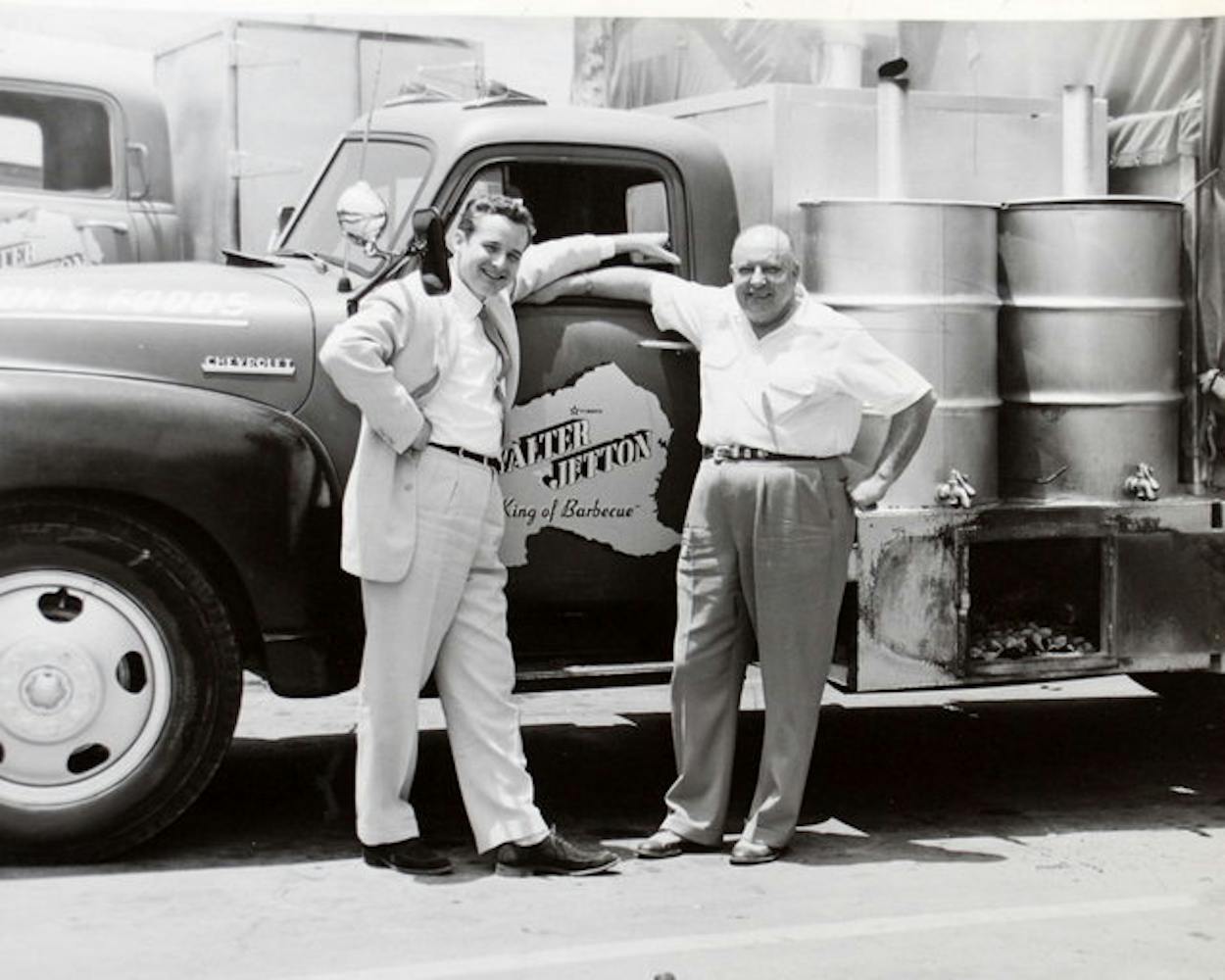

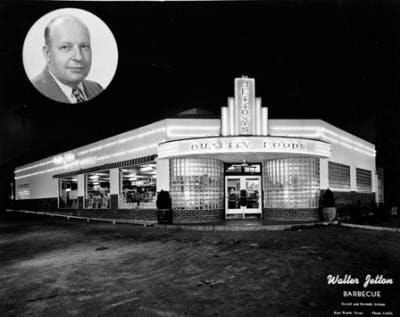

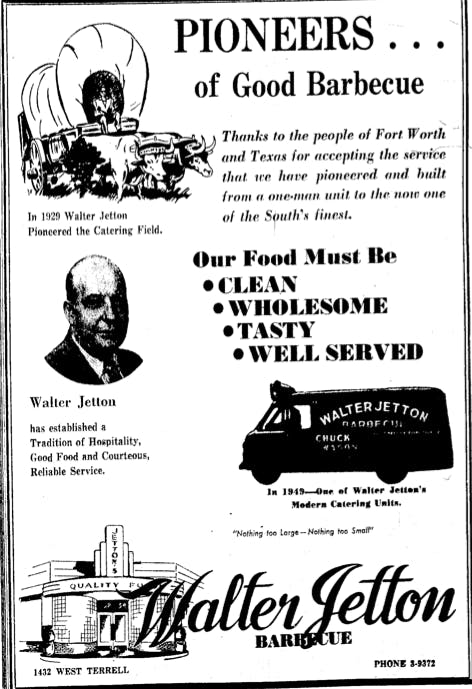

Those who remember his Fort Worth restaurant likely dined at the location he opened in 1946 on the corner of Seventh Street and Terrell Avenue. A hospital has since taken its place, but for a couple of decades Walter Jetton Barbecue churned out heaps of smoked meats in its cafeteria setting. A 1949 ad in the Fort Worth Star-Telegram touted Jetton’s catering and fleet of vans, or “modern catering units” that Jetton dubbed “chuckwagons.” These vans soon became the symbol of Jetton and his traveling band of cooks and servers, and at the height of his fame he had eighteen of these “chuckwagons” in service.

Jetton was respected enough locally to get the call when 10,000 Shriners needed barbecue in August 1950, and a few months later he fed 7,500 Baptists at a convention at the Will Rogers Memorial Coliseum.

But 1951 was the real start of his meteoric rise to fame. Fellow Texan Sam Rayburn, who was Speaker of the House at the time, invited Jetton to Washington, D.C., to cater the Texas State Society dinner. This was likely his first introduction to then–U.S. senator Lyndon B. Johnson, who would later make him world famous.

The Texas State Society was the furthest he’d traveled to cater, but Jetton was already calling himself the “National Barbecue King.” The Dallas Morning News reported on the menu, which included “pit-cooked barbecue beef, ranch-style beans, southern-style potato salad, cole slaw, stewed fruit, sliced pickles and Spanish white onions,” which was impressive enough to earn him an invite back to the dinner the next year. By then, his ads in the Fort Worth Star-Telegram freely used the term “King of Barbecue,” and Texas mail addressed as such was properly routed to his restaurant. A legend had been born.

In 1956 Jetton landed a five-page profile in the nationally distributed Saturday Evening Post. He told his interviewer of his catering business’s struggles when it began. “The first year I lost my shirt,” he said. “The second I lost two shirts.” He came off as a humble and affable character, but also a shrewd, adaptable marketer. Before that first catering gig in D.C., his friend C. L. Richart persuaded him to wear what amounted to Western costume to the event to “play up the Western angle.” He put on a cowboy hat, boots, and a colorful shirt, and the bespectacled butcher transformed himself into a cowboy cook.

Jetton was an early adopter of smoked brisket. When the Saturday Evening Post chronicled his transition from butcher to pitmaster, it noted that when Jetton took over Williams’s butcher shop in the forties, “he built a smoke pit in the back of the store and learned to barbecue ribs, brisket, clod, sirloin butts and other slow-selling items.”

Some later profiles of Jetton relied too heavily on recipes from the famous LBJ Barbecue Cook Book to characterize his barbecue, assuming his directions for cooking over direct heat meant that he eschewed the smoked variety. He told the Dallas Morning News, however, that “smoke is the secret,” and commented to the Saturday Evening Post that “wood from any tree that produces a sweet nut can be used.” (But he preferred Central Texas oak.)

The New York Times helped clarify these conflicting reports—Jetton’s catering style differed from his restaurant operation. “Mr. Jetton has two methods for grilling and barbecuing. At the cafeteria the meats are cooked in a smoke oven in indirect heat. The heat and smoke are derived from such woods as oak, hickory, walnut and pecan. On the ranch the meats are cooked directly over charcoal.” The NYT also reported on the menu at the restaurant. “The bill of fare includes, in addition to barbecue, a creditable hot chili, homemade breads, ranch beans, fried cauliflower, white beans, charcoal‐grilled steaks and numerous desserts.”

Jetton began traveling so much in his “chuckwagons” that he needed someone to watch the pits back at the restaurant. The Saturday Evening Post reported that in 1956 Jetton tapped Ethan Boyer, a sixty-year-old black man who had worked with him for thirty years. The Post said Boyer commanded three separate grills where “as much as 20,000 pounds of meat” could be smoked daily. That’s an astounding amount of meat (it’s possible they added a zero), but just as unlikely was seeing credit given to an African American working behind the scenes. And Boyer was described not as a cook, but as a “barbecue expert.”

The numbers out on the catering circuit were also astounding. In 1955, Jetton’s catering company cooked “500,000 pounds of beef, 100,000 pounds of ribs, 100,000 pounds of chicken, 75,000 pounds of ham, 50,000 pounds of sausage …” That year he catered jobs across Texas and in Phoenix, Atlanta, New Mexico, Louisiana, Pittsburgh, and Washington, D.C. By the time of the famous Sparerib Summit (more on that later) in 1964, Jetton’s fleet of chuckwagons was feeding 1.5 million people per year, according to the Dallas Morning News.

Jetton was well acquainted with politicians, but according to Sports Illustrated he could also play the part of lobbyist. When the Fifty-second American Bowling Congress championship was held in Fort Wayne, Indiana, in 1955, the ABC tournament committee was planning a vote on where to hold the next championship two years later. The front-runner, Miami, was upset by Fort Worth in large part due to Jetton’s traveling barbecue crew:

On Tuesday, Chamber of Commerce members passed out straw ten-gallon hats and red bandannas—not only to bowlers but to every pretty Fort Wayne girl. On Wednesday, Walter Jetton, who calls himself King of Barbecue, drove into town from Fort Worth with a large truck equipped with kitchen, a trailer containing Texas chickens and sides of longhorn and a chuck wagon. From the wagon he and his helpers, garbed as cowboys, passed out barbecued meats to bowlers and that night threw a special party for executive committeemen and the press.

On Thursday, when the delegates voted, it was 52 for Fort Worth, 11 for Miami and one for Buffalo. Jetton repacked his gear and returned to Texas, but the women of Fort Wayne were still wearing ten-gallon hats and, as a local columnist said, he wouldn’t be surprised if most of the population went to Fort Worth for their vacations this year.

I guess it’s not too surprising that bowlers would favor barbecue over stone crabs.

A few years later he would begin cooking for Lyndon Baines Johnson at his ranch outside Johnson City. As a senator, Johnson hosted the Mexican president, and once he became vice president the German chancellor came for dinner. Jetton catered them all, roasting beef quarters on a spit and huge racks of spare ribs over charcoal. He understood that part of his job was to put on a show: one archive video shows him basting a whole steer to welcome diners as they arrived.

But his crowning achievement—cooking for a president—happened later than he expected. He was tapped to cater a grand dinner in Austin to welcome President John F. Kennedy, but the revelry quickly became mourning when the news of JFK’s assassination in Dallas made it to the capital. Jetton was left with 3,500 KC strip steaks that never made it on the grill. But just a month later he would have another chance at feeding the leader of the free world.

It was dubbed the Sparerib Summit, and it was the first official state dinner where barbecue was the main attraction. Like a dozens of events Jetton had catered for Johnson up to this point, it was scheduled at the LBJ Ranch, but it had to be moved to the nearby Stonewall school gymnasium because of bad weather. Spareribs, German potato salad, and coleslaw were on the menu, and Walter Jetton was in the national spotlight.

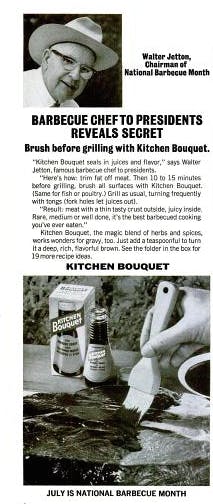

After the event, Jetton was profiled by the New York Times, the Dallas Morning News, and Time magazine. He became the spokesman for National Barbecue Month and a paid ambassador for Kitchen Bouquet, a browning sauce that your grandmother probably used in her gravy. This popular barbecue master even caught the eye of Hilton Hotels, and they brought him to France to cater the opening of their a new Paris hotel in 1966.

Jetton was on top of the world until his health began to deteriorate. He sold his business in 1968 and died later that year from a heart attack. He was 61. The company tried to continue the catering operation without him, but it folded soon after in 1975. Today, the Jetton name rings familiar to few aside from presidential or barbecue historians and some Fort Worth residents with fond memories of his restaurant. Jetton may have given himself the title “King of Barbecue,” but for a few decades he certainly deserved it.

Many of the photos above came from a memorial website to Walter Jetton that was created by his grandson Chris Jetton. Many more photos and Jetton’s LBJ Barbecue Cook Book can be found there.

- More About:

- Black BBQ