Sprinkle it on, rub it in, or shake it over the meat. It doesn’t really matter how you apply it, if it’s seasoning for barbecue, it’s called a rub.

To really examine meat the almost inseparable relationship between meat and rub, you have to back a few millenia. For thousands of years, salt has been sprinkled on freshly-harvested meat as a way of preservation, but that’s a very different process for a very different story one day possibly down the line. To find something akin to what we know as “rubs” today, you have to fast-forward quite quickly through time to the more recent history of the Civil War-era South. For generations, meat cooked over direct heat was doused in a wet “mop sauce.” Wesley Jones, a slave from South Carolina, talked about his antebellum-era mop sauce in a Works Progress Administration slave narrative (dialect reprinted):

I used to stay up all night a-cooking and basting de meats wid barbecue sass (sauce). It made of vinegar, black and red pepper, salt, butter, a little sage, coriander, basil, onion, and garlic. Some folks drop a little sugar in it.

This technique of mopping still occurs regularly through the South (Rodney Scott’s spicy mop sauce has made the whole hog at his South Carolina location of Scott’s barbecue famous around the country), but most Texas pitmasters skip the wet method and stick with a dry rub.

Proprietary recipes for meat spice mixtures are nothing new. Eighteenth century cookbooks included recipes for something called “kitchen pepper,” like this one from Charlotte Mason’s 1797 cookbook that included salt, pepper, cinnamon, and ginger. A century later, Ana Marie Morris of Baltimore also had a kitchen pepper recipe, which added cloves, allspice, and nutmeg to Mason’s mix (that doesn’t sound like something I’d want on my brisket).

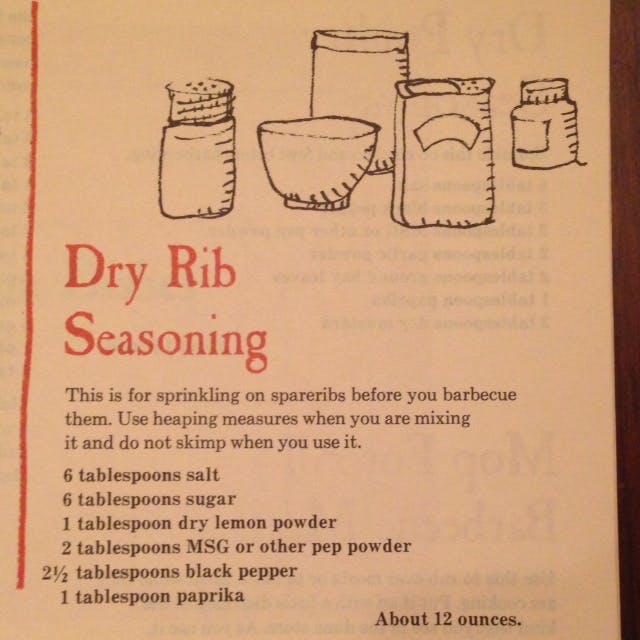

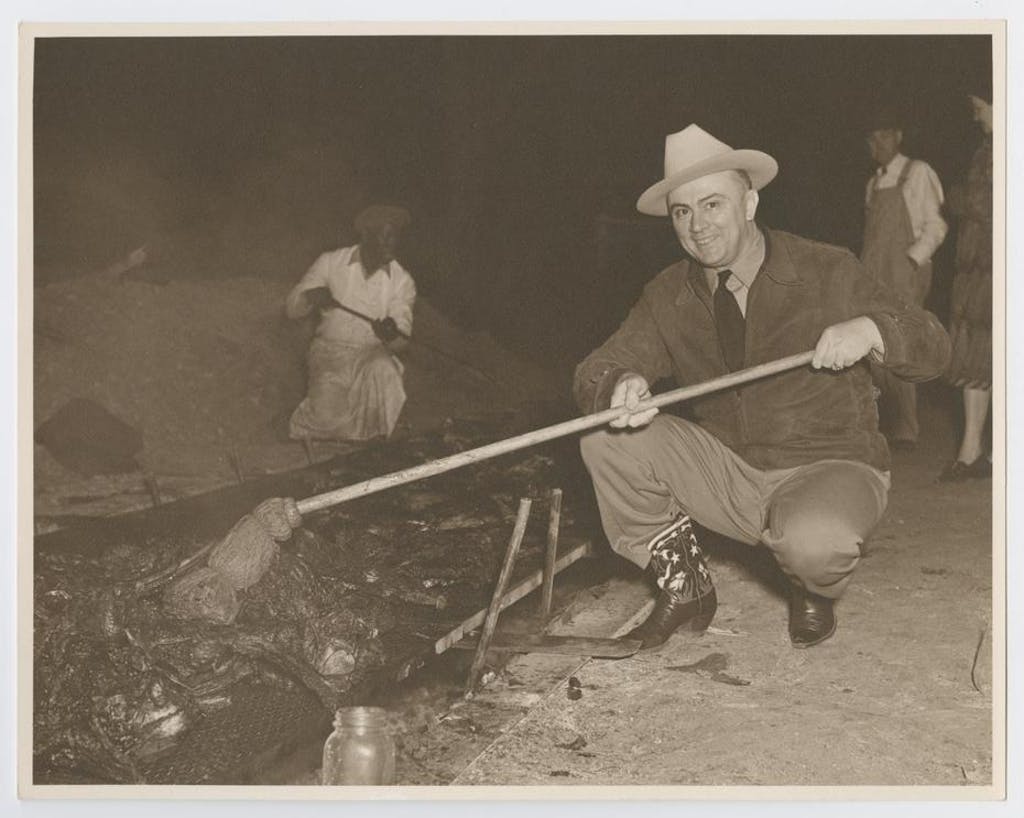

The instance I found of what could be considered a recognizable rub recipe is from the 1965 cookbook, Walter Jetton’s LBJ Barbecue Cookbook. Jetton’s “Dry Rib Seasoning” includes salt, pepper, sugar, and paprika (the primary building blocks for most modern rubs); MSG (an ingredient that’s a little taboo these days); and dry lemon powder (which now might be hard to come by).

The term “rub” was still novel as recently as 1979, as evidenced by a story printed in the Dallas Morning News. In it, journalist Dotty Griffith reported on the annual Wild Game Dinner for Austin politicians held by the Sportsmen’s Club of Texas, putting the term “barbecue rub” in quotations marks. Even for a seasoned food writer, it wasn’t yet a common seasoning parlance, but the recipe that was published in the DMN few months later sounds familiar—it included sugar, salt, pepper, chili powder, garlic powder, cumin, and cayenne.

I don’t think it’s a coincidence that the rise of the dry rub coincided with the rise of the backyard offset smoker. Smoking with indirect heat meant you could leave the meat alone during the cooking process, that mopping wasn’t necessary. This allowed cooks to put as much seasoning on at the beginning of the cook, knowing it wouldn’t be washed away with a wet mop. It also meant ingredients like sugar could be used without risking that it would burn up under the intense heat of direct heat cooking. Modern barbecue rubs are designed for low and slow cooking.

Every two years, the Hearth, Patio & Barbecue Association (HPBA) collects consumer information on barbecue trends. From 2009 to 2013, backyard barbecue cooks regularly using dry rubs rose from 14 percent to 33 percent. Some of that increase can be attributed to the popularity of television shows like BBQ Pitmasters. On the screen, as much emphasis is placed on the rub for the success or failure of the barbecue as is placed on the pitmaster. You could make a drinking game out of how many times you hear “flavor profile” in every episode. That “profile” is largely built on multiple applications of different barbecue rubs.

And rubs are big business: you can even buy the rub from host Myron Mixon on his website for nearly a dollar an ounce. Other commercial rubs—some loaded with sugar and salt, i.e. cheap ingredients—still fetch a high price despite the low price points of their basic ingredients. I examined the cost of one commercial rub versus a homemade version and found a ten-fold markup. That’s why restaurants don’t usually bother buying a pre-made rub.

Some joints don’t even bother with any seasoning. Billy McDonald of Mac’s Bar-B-Que n Dallas explained to me why it’s all about meat and smoke to him. “Why do you need to put seasoning on your meat if you’re buying good quality meat?” To McDonald, seasoning just gets in the way. “You come here to taste the meat.” That’s an extreme position, even for the most conservative pitmasters in Texas, the state known for the Dalmatian rub: salt and pepper. That’s what some of the newest joints like Franklin Barbecue in Austin and Snow’s BBQ in Lexington use on their meat, along with some of the oldest like Louie Mueller Barbecue in Taylor and Kreuz Market in Lockhart. (Okay, Kreuz adds a little cayenne into the mix, but you get the point.)

That covers all of Texas Monthly‘s latest Top 4 BBQ Joints, except Pecan Lodge. They smoke everything the old school way with just wood smoke, but their rub is a little more complicated. Eater shared in its profile of the Justin Fourton that “Pecan Lodge’s blend includes Lawry’s seasoning salt, granulated garlic, black pepper, chili powder, mustard powder and paprika.” That chili powder and paprika give the rub that familiar red color. Most any commercial rub being sold today is red, which seems to be what consumers associate with a barbecue rub. But is paprika the best spice to pair with beef and pork?

Chefs around the country were polled by authors Karen Page and Andrew Dornenburg, who compiled that input into their book, The Flavor Bible. It matches up ingredients with other complimentary ingredients. Under beef brisket they list black pepper, salt, garlic, and brown sugar, but not paprika [though it is listed as complementary for pork ribs]. That doesn’t mean it can’t work with beef, but it’s a reminder that building your own rub allows you to develop something based on your own tastes. Take out those spices from the cabinet and see if you like them before blindly following a recipe. You may have an aversion to garlic powder or find allspice offensive. If you’re looking to prefect your barbecue recipe, you might as well start with flavors you know you like.

In fact, I’d suggest to backyard cooks just starting out to begin simply with just Kosher salt and cracked black pepper. It’ll make prep time a lot simpler, and will allow you to focus on the cooking technique. Like any good science experiment, you want to eliminate variables. Get your technique right, and you might find that salt and pepper is enough, or maybe it’ll be time to add some flavor. If you do have the itch to create your own specialty rub, remember this when building the recipe: Ingredients like sugar and salt have the ability to dissolve into the meat, but not much else. Paprika, cumin, chili powder, garlic powder, and anything else with powder in the name are just that—powders. They will sit on the surface of the meat throughout the cooking process. If these powders become too high of a proportion in your recipe, then you’ll end up with a gloopy mess of wet rub on the meat instead of a good bark.

This weekend is the perfect time to build your own signature rub that is sure to compete with the big boys on the supermarket shelves. If you truly want to replicate some of the most popular rubs out there, you’ll have to special order specialty items like honey powder or grains of paradise, but it’ll still be a lot cheaper than paying for someone else’s packaging. And who knows, maybe you’ll just settle on good old salt and pepper, and spend your extra money on another pork chop.