With the rise of review sites like Yelp and the ascent of food blogging, restaurants are scrutinized more than ever. Traditional restaurateurs have long understood the power of a negative review, but concern with the critics was rarely something that barbecue joints worried themselves with. But the barbecue zeitgeist—which I recognize that I, the Barbecue Editor, have played a significant role in perpetuating—has brought increased attention to this cuisine, making it a target of criticism the likes of which pitmasters have never experienced. Not only has the wave of amateur opinions swelled, but professional food critics that once viewed barbecue joints as too provincial to consider for the pages of their magazines and newspapers are now adding their critical observations. So now, the fickle food that is smoked meat, a foodstuff cooked using a notoriously difficult-to-master technique, is no longer veiled by a curtain of smoke. The stakes are higher, and as a result, restaurateurs and pitmasters are striving to produce consistently great quality.

And for some pitmasters, continually hitting that high mark means using high-grade meat. This fancification of barbecue has certainly raised some eyebrows, as evidenced by an email I received last week from a reader who noted how much focus Aaron Franklin puts on the specific quality of meat in his new book, Franklin Barbecue: A Meat-Smoking Manifesto. In it, Franklin writes “I use Prime Grade, which is by far the most expensive, but its marbling is important to the style of barbecue I’m going for.” The reader, referring to this passage, asked:

Is this the new standard by which the rest will be judged? One almost has to be an elitist to be able to procure these items. This goes against all that barbecue should be (simple, traditional, a common man’s meal).

Okay, its a more expensive grade of brisket, but it’s not like Franklin switched to smoking filet mignon. So perhaps what really got the reader lathered up was this line from Franklin: “What’s most important to me is that the beef we use comes from ethically treated cattle who are raised and slaughtered in a peaceful, comfortable environment.” I’ll concede that this kind of meat is definitely more expensive and certainly a little more difficult for the average Joe Smoker to buy, but its hard to fault a restaurateur for having ethical standards for beef, even if he’s just cooking barbecue. Even so, as I wrote last year in a column about all-natural beef, Franklin is still among a small minority of Texas barbecue joints purchasing beef based on animal welfare standards, though plenty are now looking more closely at the grade of beef they’re using.

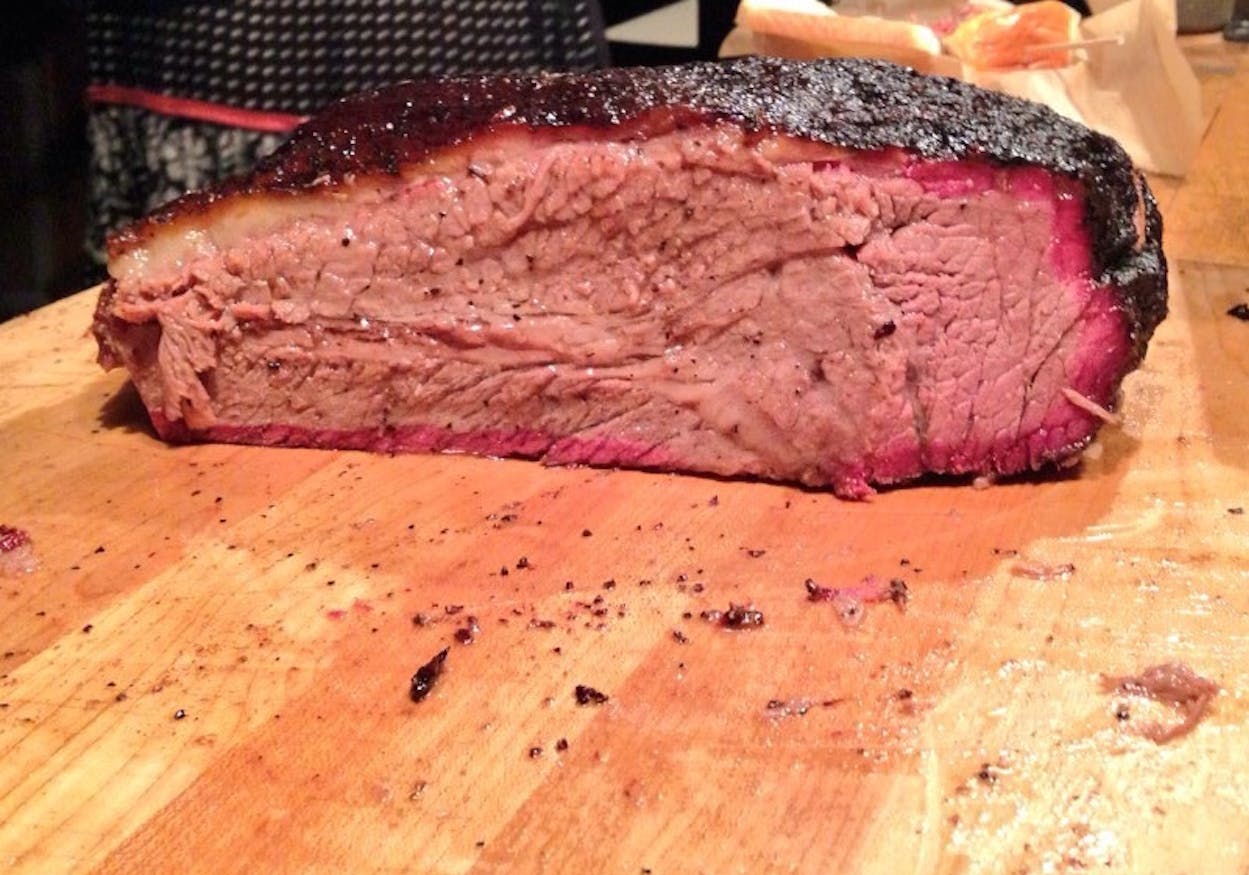

But don’t we want restaurants to take food to the next level? Isn’t a better-than-home-cooked experience what we’re paying for when we slap down money for food someone else has prepared? And for barbecue joints, where the meat is center-stage, it makes sense that pitmasters would turn to better beef to raise that bar. So while prime is the highest USDA grade and is therefore the most expensive (more on brisket grades here), it also has the most marbling, or intramuscular fat, the stuff that melts within the meat during the cooking process and keeps it moist. If you’re smoking briskets every day that will be highly scrutinized by an increasingly noisy public, wouldn’t you use a better grade of brisket to ensure you don’t get a one star review for bone-dry brisket? At places like Franklin Barbecue, where there are probably several Yelpers in line daily just dying to get some bad brisket so they can post a triumphantly negative review, it’s no wonder he makes the costly decision to use the more expensive Prime. Juicy brisket makes for good food makes for happy food critics.

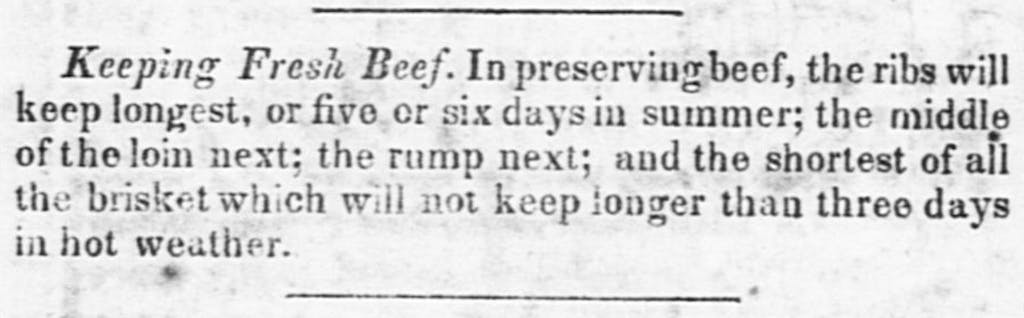

The notion that using good beef is somehow antithetical to the capital-T “tradition” of barbecue is also a little off. Let’s examine the characteristics of a Traditional Texas brisket, like one that would have been served in an early twentieth-century meat market. Since confining cattle and feeding them grain hadn’t yet come about, that Traditional brisket would have come from a free-ranging, grass-fed steer, and it would have likely been from a tall, slender breed like a longhorn. Now take that raw, tough, skinny brisket and let it sit on an unrefrigerated shelf for three days (see notes from 1848 on “Keeping Fresh Beef” below), at which time it would deemed ready for the smoker just before it turned too green to consider consuming. Be careful what you wish for, because if it’s just tradition you’re after, you’ll probably be eating alone.

Another comment from that email is that “one almost has to be an elitist to be able to procure these items.” Sure, brisket you can get at the grocery store is likely not the same as what many of the highly-regarded barbecue joints across the state are ordering. Chances are that all you’ll find at your local grocer are very large Select grade briskets from commodity cattle. Finding Choice, the grade above Select and below Prime, can be tough, and it’s nearly impossible to find Prime or Certified Angus Beef (or CAB which is a very popular choice at Texas barbecue joints). You have to belong to a club like Costco or have a card for Restaurant Depot, which accepts only restaurateurs as members, to have regular access to these cuts of beef. I guess that’s a little elitist, but it’s worth noting that the most ambitious and delicious hamburger joints in town probably aren’t using your grocer’s ground chuck. It’s true in many ways, but remember that a rising tide lifts all ships. Better barbecue at one place means that people come to expect better barbecue at all places. And greater demand for higher quality beef means ranches have to raise their standards too. These are benefits for the eater at large.

The final comment I wanted to address is that barbecue should be simple. I agree, but I don’t think using better beef is a symptom of a more frilly barbecue experience. We’re actually in the midst of a rush toward simplicity in Texas barbecue. Wood-only cooking has never been more revered than it is now in Texas barbecue. A steel offset smoker has never offered so much cache, and even northern journalists are happy to eat sauceless barbecue with their hands. Simple has come to mean authentic, and Texas barbecue isn’t having any problems with authenticity.

So perhaps this reader is hinting at a question I’ve been asked before: with its rise in popularity, is Texas barbecue losing its soul? Absolutely not. In fact, with this barbecue revival, I’d say that heightened attention is kind of saving its soul. Let’s not use one side of our mouths to complain about dry brisket, while the other side questions the use of anything but the least expensive beef on the market. Better beef makes for better eating which brings more people to the table, and that’s what is needed to keep the soul of Texas barbecue alive.