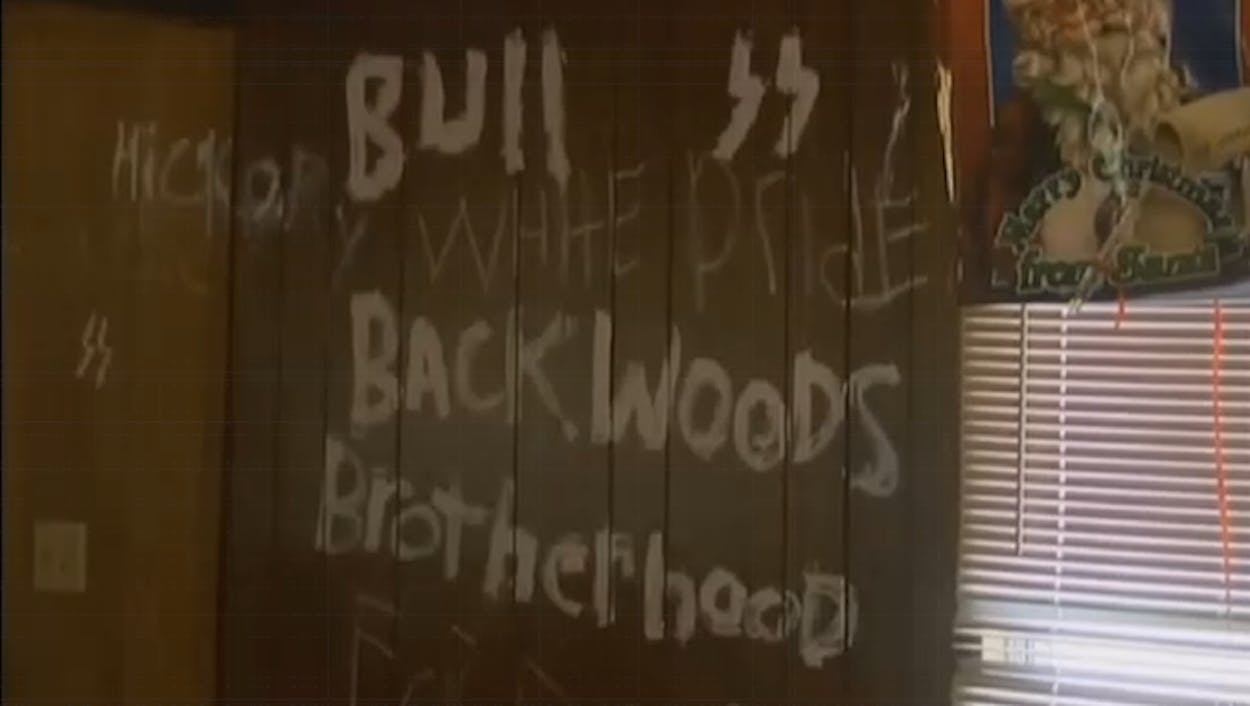

If you read this story, or watch the accompanying video, about a house that was broken into and vandalized in Noonday — about ten miles outside of Tyler — you might not notice something the camera only briefly lingers on. As Smith County Sheriff’s Lieutenant Paul Black talks about the drug and meth problem in the area, and the news anchor wonders aloud about the perpetrators’ motives, neither of them mention that whoever broke in tagged “white pride,” “backwoods brotherhood,” and the Nazi SS symbol on the wall.

Howard Davenport, who inherited the house from his parents, is white, as is his fiancée, Linda Burns. It’s hard to know exactly how to characterize racist messages and symbols when the victim of the crime is white, but doesn’t the fact that the crime was committed by a group of people who like to draw Nazi symbols and scrawl “white pride” seem worth mentioning in the newscast?

But that’s how race works in the media: Unless it’s proven beyond the shadow of a doubt that a person’s actions were racially motivated, we err on the side of “we don’t know if it’s racist or not, so maybe we shouldn’t even talk about it.” And that is part of the reason that we’re embroiled in an ongoing national debate about the artifacts of the Confederacy that litter the South, some of which, of course, remain throughout Texas.

At Richland High School in Tarrant County, mascots the Dixie Bells and Johnny Rebs have come under fire in recent weeks. KXAN reported on a North Richland Hills rally in support of the mascots:

Hundreds of people rallied Sunday to keep the rebel names, maintaining the Dixie Bells and Johnny Rebs are not divisive words.

Scott Maywald of Fort Worth attended the rally and draped a Confederate battle flag over his vehicle.

“Everybody’s saying (the rally) is not about the flag, but it is about the flag,” Maywald said. “It’s all connected. It’s not one thing. They’re trying to take the peoples’ rights away, one at a time, and that’s not right.”

If it’s never about race, then a person can make the argument that “Dixie Bells” and “Johnny Rebs” aren’t divisive with a straight face. Under that assumption, those names are just words divorced from any context. The real issue, if it’s not about race, becomes whether it’s fair to strip away a school’s right to make black students be Johnny Reb — the personification of the Confederate soldier in the Civil War.

That’s a message that’s likely to be popular in Evadale, north of Beaumont. Here’s the school district’s website:

Evadale’s mascot is the Rebels, and passing through the school students walk by a number of Confederate symbols. But though the Evadale superintendent declined KXAN’s requests for comment, the station did speak to the high school valedictorian, who explained that they were symbols of pride:

The Confederate flag has never been used to discriminate against students or any group, but, rather, is a symbol of pride at the school, Class of 2015 valedictorian Jamie Richardson said.

“We should be able to have the right to fly that flag and that’s an individual right,” she said. “But I can see where it would possibly offend someone and I know that as a person who cares about people and loves people that I could understand if someone wanted to express their opinion about how it would be wrong to fly that flag and I just think we should understand it from all points of view.”

For the past month, the nation has focused on such lingering symbols of the Confederacy. It’s been everywhere—when President Obama visited Oklahoma Wednesday night, he was greeted by protesters waving the flag outside of his hotel. Earlier in the month, activist Bree Newsome became the subject of memes when she scaled a flagpole at the South Carolina state Capitol and took down the Confederate flag.

The debate was sparked when nine people in a historically black church in Charleston were murdered. Dylann Roof, who was arrested for the crime, liked the Confederate flag a lot, and the dissonance of seeing mourners and coffins pass underneath that same flag flying above the state’s Capitol eventually proved to be too much. The flag came down in South Carolina, which led to its removal in Alabama and beyond.

But even the shooting in Charleston, where Roof reportedly said that he was there “to shoot black people,” got waved into the ambiguous morass of a country—and a media culture—in which it’s never actually about race. The day after the shooting, Fox and Friends hosts pushed the idea that Roof was motivated by “a rising hostility to Christians,” and called it “extraordinary” that police labeled the mass murder of nine black people in a black church by someone who said he was there to shoot black people a hate crime.

The tragedy was a month ago now. And as we debate whether racism is still prevalent in the U.S., the pain that accompanies Confederate symbols — which Roof celebrated — is causing increased tensions.

Last month, we saw Confederate statues at the University of Texas painted with the message “Black Lives Matter.” And this week in Dallas the defacing of icons continues:

Officials say someone has vandalized a statue of Confederate Gen. Robert E. Lee at a park named in his honor in Dallas’ Oak Lawn neighborhood.

Dallas police say they received two calls Friday morning after people say they saw the word “shame” spray-painted on the base of the statue. The city’s Park and Recreation Department had workers use a power washer to clean the statue later that morning.

The statues in Oak Lawn and at UT will remain as we talk about whether clinging to the heritage of the Confederacy is racist or not (though the institutions that house them will probably need to keep a budget for security and power-washing), and students and administrators who show their Rebel pride can talk about how welcoming and inclusive their schools are. That’s something we’re able to do in a country where talking about race is scarier than actual racism. And when a guy who loves the Confederate flag and international racist symbols goes into a black church and says he’s there to shoot black people, we can debate whether he was racially motivated, because who the heck knows what that really means?

If we’re skittish when talking about race, that manifests in the police and media choosing not to mention that a group left SS symbols and “white pride” tags in a stranger’s house. And if that elements like that are consistently ignored, then we don’t watch for the sort of violent racism that ends in death. After the shooting in Charleston, Dylann Roof’s friends confessed to shrugging off troublesome things that he’d said. Roof might have said hateful, racist things—but if nobody wants to talk about it, then how do we know when to take it seriously?

Linda Burns told me on the phone that the kids—she heard from a witness that they were teenagers—who vandalized her fiancé’s house in Noonday had a Rebel flag license plate. “I think the racial parts came from all of that stuff with them fighting over taking down the flag,” she said. “It made me sick. We’ve never had nothing like this here.”

That might be true, and it might not—but if the media won’t even talk about it when it does happen, how will we ever know when it actually is about race? Unless, of course, nothing ever is.

(image via screenshot)