The past week has not been the most inspirational chapter in our political history, thanks to various developments related to Donald Trump’s bid for the Republican nomination. In particular, Friday evening’s news from Chicago, where Trump cancelled a rally in response to reports of tension between his supporters and the protesters who had arrived en masse, were ominously evocative of certain outright grim chapters in American political history.

There was little consensus about the underlying causes of the dismay. Some Americans put the blame on Trump, noting his history of casually encouraging his supporters to respond violently to any dissenters in their midst, and his subsequent threats to take a punitive approach to any other protesters who were thinking about scaring him into canceling his own rallies. Some Democrats were quick to argue that Trump’s party, too, has some culpability, as do his remaining rivals for the Republican nomination. Trump himself was taken aback by such observations. “I don’t accept responsibility,” he said on Sunday, in a rare moment of honesty during his most recent round of cable news appearances. Trump’s supporters, needless to say, shared his view of that; in their assessment, they are the victims, and an incident on Saturday, when a protester rushed the stage in an attempt to seize the podium from Trump, inflamed their sense of grievance.

I agree with partisans on both sides that it’s worth considering why a candidate like Trump, or Trump himself, would resonate with so many Americans; that’s why I’ve been brooding over Trump’s campaign since August. And to make a long story short, I’d agree with Democrats that the Republican Party in general is long overdue for a reckoning; I was calling for one way back in 2012. But I would remind Democrats that they’re not innocent either: there are plenty of people on the left who take an opportunistic approach to moral outrage, proclaiming their own virtue en route to denouncing Republicans for falling short. And, if we’re having a formal inquiry on the Trump enablers, I’d argue that some share of the responsibility lies with the inquisitors on all sides, who are more interested in laying blame for Trump’s ascendancy than in trying to mitigate the ills that have attended it or curtail the risks that his election as president would represent.

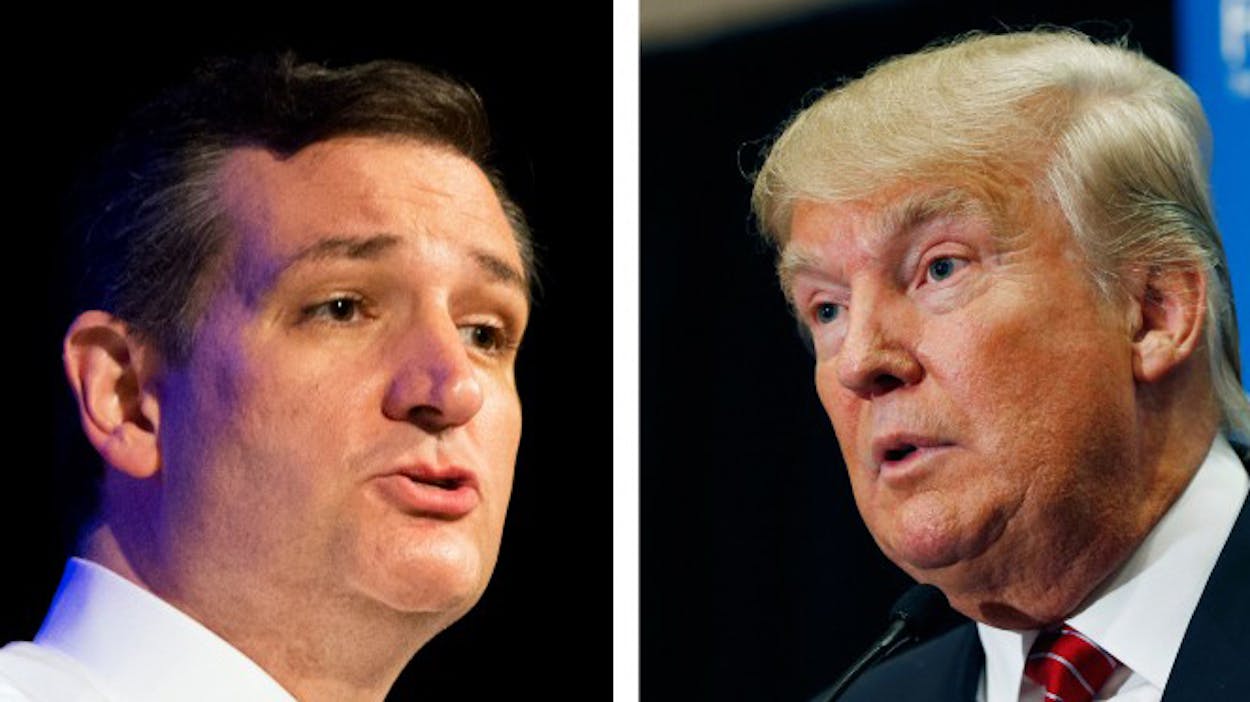

The blame, in other words, can wait. In my view, we should focus on dealing with the imminent problem. We’re about halfway through the primary calendar, and five more fairly large states will vote today: Florida, Ohio, Illinois, Missouri, and North Carolina. There is still time to stop Trump from winning the Republican nomination. And there’s still a way to do so: Republicans can thwart Trump’s bid for the presidency by coalescing around the junior senator from Texas, Ted Cruz.

This would, of course, require Republicans to coalesce behind an alternative that many of them find deeply unpleasant, and whose relative success in the first half of the calendar strikes many of them as unsustainable, if not an outright fluke. Those concerns about Cruz, I think, help explain why many Republicans are already expecting, or hoping, that the nomination will be decided at the convention in July. That’s a real possibility. A candidate needs 1,237 delegates to win the nomination. Trump currently has 460, which is fewer than Mitt Romney and John McCain had amassed at this point in 2012 and 2008 respectively, and gives him a relatively narrow lead over Cruz, who has 369. Today’s primaries are momentous for Republicans pinning their hopes on keeping Trump from hitting the critical threshold. Two of the states voting today allocate delegates on a winner-take-all basis and both, as it happens, have an incumbent statewide leader on the ballot. If John Kasich wins 66 delegates in Ohio and Marco Rubio wins 99 delegates in Florida, it will be highly unlikely that Trump makes it to the convention with a majority of delegates.

If it comes to that, I’ll hope Republicans are receptive to the argument that Ross Douthat laid out elegantly a few days ago, in favor of a party’s right to blatantly reject the preferences of its voters. As Douthat notes, it would be an ugly exercise and might mean the end of the GOP as we know it. But if the GOP didn’t want to go to the glue factory it shouldn’t have succumbed to the pathologies that have enabled a number of invidious opportunists. And it’s worth noting that the Republicans do have one potential standard-bearer who can offer a reasonable response to the small-d democratic concern that voters matter, even in a constitutional republic: Mitt Romney won his party’s nomination the normal way in 2012, so he has already been vetted by We the People.

But denying Trump the nomination at the convention should still be understood as a backup plan. Regardless of today’s results, Cruz will have a mathematically plausible chance of overtaking Trump in the delegate race. In my view, all Americans, including his critics, and Trump’s supporters should hope that he does; Cruz has plenty of foibles, but he’s not worse than Trump. And as Jim Newell argues, at Slate, anyone pinning their hopes on a contested convention has a vested interest on Cruz’s continued success, if only because a conspiracy directed at denying him the nomination will aggravate his supporters, who are considerably more temperate than Trump’s.

In my assessment, Cruz’s prospects in the forthcoming primaries, accordingly, are better than people expect. Some of his wins to date have been discounted, deliberately or not, but there is a reasonable explanation for the perception that it’s all downhill from here. It’s been almost a year since Cruz announced his bid for the nomination at Liberty University, a clear signal that he would seek to rack up delegates in the Southern states, where evangelical voters make up a large swathe of the Republican electorate. The fact that Trump romped to victory in every state in the Bible Belt has been widely taken to mean that Cruz’s strategy failed. And it’s true that Cruz didn’t anticipate how much success Trump would find among evangelical voters. But in fairness, no one did. No one would have, really, because if these voters are identifying themselves as “evangelical”, it would be strangely churlish to suspect they’d go for the candidate who likes to eat the little crackers they pass out at church but bridles at the suggestion that he might need God’s salvation.

What people are failing to appreciate, I think, is that at some point Cruz clearly retooled his strategy. Like all the candidates who threw their hat in the ring this year, he had no choice but to do so, thanks to Trump, who has turned out to be not just a disruption, but an unusually baffling, powerful and shape-shifting black swan—an angry non sequitur in human form, buoyed by his personal wealth and fame; enabled by allies in his natural habitat, cable news; and insulated by his own inexplicability.

In any case, Cruz’s recent line of criticism—that Trump has been part of Washington corruption for 40 years—shows that he’s revised his strategy. This anti-establishment message is more likely to resonate with Trump supporters, especially since Cruz happens to be a credible messenger when it comes to bedeviling the establishment. The evidence thus far suggests that voters who want to Make America Great Again are also interested in plans to Make D.C. Listen. About two dozen states and territories have voted thus far. Almost all of them have gone for Trump or Cruz. Even more strikingly, in virtually every contest, Cruz and Trump together have won between 60 percent and 80 percent of the total votes cast. A telling exception came on Saturday. The D.C. caucus offered a snapshot of the establishment’s preferences; the results turned out to be a mirror image of most previous contests. Rubio narrowly edged Kasich, with 37 percent of the vote. Trump was a distant third, and the bragging rights went to Cruz, who finished dead last, with just 12 percent.

Rubio and Kasich, of course, are calling for a more moderate, conversational approach. There’s nothing inherently wrong with that message, but it doesn’t seem to be very popular at this time. Halfway through the primary, a majority of Republican voters seem to be in the mood make themselves heard, that’s a pattern that’s transcended the traditional divisions like region, religion, ideology, and there’s no reason to think the pattern won’t persist. That being the case, last weekend’s events should remove any doubt about whether it’s better for them to be led by Trump or Cruz. The latter might give you a lecture. The former has vowed that he won’t leave it at that.