On April 14, 1976, Ronald Reagan stared in the face of political oblivion. Reagan, who was facing off against incumbent Gerald Ford in the Texas Republican presidential primary, knew that losing Texas meant the end of his campaign. And winning required dispensing with party purity. In Houston, Reagan appealed to “November Republicans”—Democrats who voted in their primary in May and then voted Republican in the fall—to vote for him against Ford. “I think the election here concerns not just Republicans versus Democrats,” Reagan said. “I’m trying to appeal to a broad base of those whose philosophies are similar to mine. I wish they wouldn’t wait until November. I wish they would cross over now.” They did in droves, delivering a Texas victory to Reagan. Although Ford eventually won the party’s nomination that year, the victory was an important benchmark in Texas politics: The success of coaxing Democrats to cross over in that election set the state on a path to party realignment.

Four decades of realigning later, the Republican Party of Texas is having an identity crisis. Mainstream business Republicans are now derisively called “Republicans in Name Only” by many of the party newcomers, and the establishment found itself suddenly shoved aside by culture warriors and freedom fighters in the Freedom Caucus. The frustration is palpable. “There are a number of us who have taken the position that we should just let the Freedom Caucus have the keys to the car, and when they drive it into the ditch as soon as they pull out of the driveway, then the adults can come back in and take the wheel,” Dallas lawyer and former county GOP Chairman Jonathan Neerman said.

This party disorientation does not portend the imminent downfall of the Republican empire of Texas. Without some unpredictable and swift change of fortune, the party will continue to dominate statewide elections—at present the Texas Democrats do not appear ready to even field a candidate for governor. But the party’s next moves could have effects for years to come. The question is whether the GOP establishment can keep the party focused on policies that promote economic growth, or if ideological purists will force party leaders into endless debates over gender and sexual identity, immigration, and abortion.

A widening split was evident in the Eighty-fifth Legislature. Lieutenant Governor Dan Patrick led social conservatives into a standoff with business-oriented House Speaker Joe Straus over transgender bathroom rights, ultimately crashing must-pass bills and forcing Governor Greg Abbott to call this summer’s special session. In the midst of this legislative flameout, state GOP Chairman Tom Mechler resigned for personal reasons, but left with a warning against party infighting. “A party that is fractured by anger and backbiting is a party that will not succeed,” Mechler wrote in his resignation letter.

The friction can partly be attributed to a Democratic party that’s too ineffective to rally against, said Neerman. Without a true outside opponent to spar with, he said, the various social conservative organizations have formed a “Justice League of the right wing” to battle against old school Republicans. “If the Democratic party was a viable option in the state, then that would allow the parties to have a real debate about policy,” Neerman said. “Instead, because on a statewide basis the Democrats have not been a viable alternative, it devolved into this civil war over bathrooms and other silly side issues that aren’t relevant to most Texans.”

And that is a precursor to another major issue: The Texas Republican Party is suffering from too much success. Party candidates have not lost a statewide election since 1994. For more than a decade, the party has held a legislative majority, thanks in part to district gerrymandering. Democrats still held 53 percent of the local elected offices when President Obama took office in 2009, but now Republicans hold 67 percent, more than 3,000 offices at the state and county level. Outside of the major cities and the Rio Grande Valley, Texas is effectively a one-party state. As a result, the party has factionalized, and the infighting is rampant.

It has been a long time coming. The modern party founders in the 1960s and 1970s were business Republicans, divided into Goldwater/Reagan conservatives and Ford/Bush moderates. Then, in 1994, evangelical Christians took control of the Texas party infrastructure. U.S. Senator Kay Bailey Hutchison—the last pro-choice Republican to win a major primary—was badgered at a county convention for her stance on abortion. A long-time party secretary snidely joked that 1994 was the first state convention where delegates asked about trailer hookups instead of hotel rooms, and a candidate for party chair was booed for declaring “the Republican Party is not a church.” A shift was beginning.

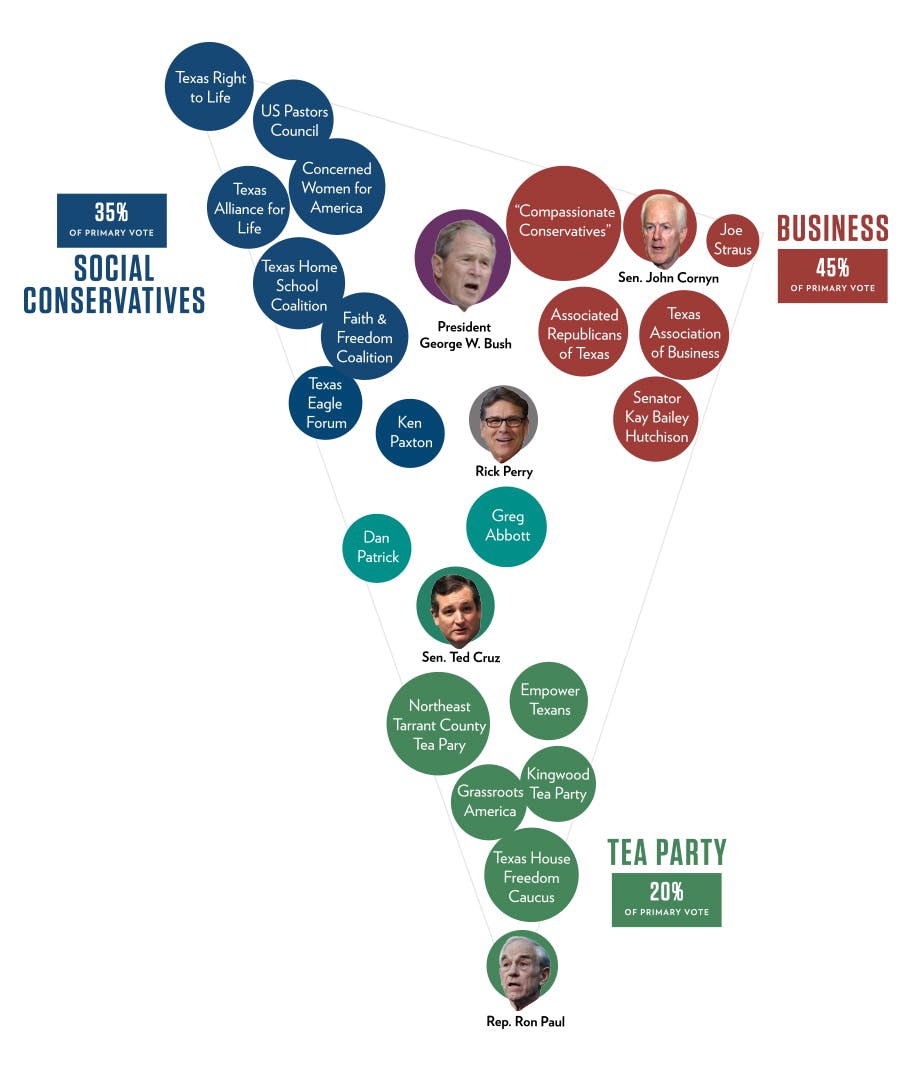

As governor, George W. Bush maintained a truce with the religious right as he pushed a business-oriented agenda of tort reform and tax restructuring in the Legislature. Governor Rick Perry also stayed friendly with the business community, but he saw the value of appealing to evangelicals on issues such as gay marriage. With Perry’s encouragement, evangelicals became an entrenched part of the party. Former congressman Ron Paul then brought libertarian-leaning supporters into the fold during his unsuccessful 2008 presidential bid. As a result, tea party groups that erupted the following year were a coalition between social conservatives and libertarians determined to make fundamental changes in government at all levels.

Although the tea party groups and organizations like the Eagle Forum, Texas Home School Coalition, Concerned Women for America, Faith and Freedom Coalition, Empower Texans, and Grassroots America are not officially a part of the state Republican Party, they operate like auxiliaries. Business-oriented groups, like the Associated Republicans of Texas and the Texas Association of Business, often have their own priorities and candidates, and that leads to proxy wars within the GOP.

Austin businessman James Dickey, who replaced Mechler as state party chairman, downplays the party’s division. “Those wings have their own preferred top issues, or maybe even have some fairly substantial differences on multiple issues. And that’s appropriate for a party that welcomes all who agree with us,” he said. Just because Republicans don’t see eye to eye on one issue, Dickey explained, they may agree on another, meaning that disagreements shouldn’t automatically end in “contentious environments.”

Former Harris County Republican Chairman Jared Woodfill, who now heads a group opposed to gay rights, sees that divide a little differently. According to Woodfill, the real problem is what he called “Strausians,” or the “liberal to moderate Republicans . . . who clearly are more closely aligned with the Democrats on many issues than they are with the Republican Party of Texas and its platform.” Woodfill also notes that Straus’s political base as House speaker is the Democratic caucus and a core group of Republicans. Straus initially won election as speaker in 2009 by building on a coalition of Democrats and eleven House Republicans. Since then, his re-election has never been seriously challenged.

Straus’s position on issues such as transgender bathroom use and public school finance reform have been in line with conservative business groups like local chambers of commerce and the Texas Association of Business. In the past, business in Texas has been practically a political party of its own, and for more than a century it existed within the once dominant Democratic party. Economic populism in the late nineteenth century tended toward farmers challenging railroads, and in the twentieth century business interests used political clout to limit union influence. As the national Democratic party moved toward civil rights and the Vietnam war, many in Texas business started seeing the Republican party as a conservative alternative.

But now, the big business relationship could be strained. One of the oldest Republican support organizations is the Associated Republicans of Texas. Founded in 1974 by the late U.S. Senator John Tower, the group probably has done more to move Republicans from holding less than two-dozen seats in the 181-member Legislature to its current majority. The ART donated more than $8 million to legislative campaigns over seventeen years and helped finance redistricting fights. Current co-chairman Hector DeLeon fears that the social conservative agenda is going to damage the Republican brand, just as liberals harmed the Democratic party in the eyes of many Texas voters, particularly those in rural areas.

“There’s nothing that says that the Republican party has a mandate from God to be the majority party in Texas forever and a day,” DeLeon said, cautioning against the members of his party who won’t acknowledge the existence of moderate Republicans. “That’s the danger you run into when the party becomes so successful that it cannot stand prosperity. And that’s what happened to the Democrats . . . They cannibalized themselves into a minority party, and if the Republican party isn’t careful, that’s what’s going to happen to the Republican party.”

Even as many Republicans agree that there is a party identity crisis, there is little agreement on how to meld the business and social conservatives into one harmonious group. For some, such as Northeast Tarrant County Tea Party President Julie McCarty, the real answer is to drive apostates out. McCarty—who once opposed a candidate because he was a Methodist, a denomination that, in her words, “believes everything goes”—said that for the Republican Party to grow, its candidates must a passionately embrace the platforms passed by activists at the state party conventions. “The party is definitely divided, and I think it will continue to be divided, simply because there are two schools of thought on what really defines conservatism,” she said. The “establishment,” she said, “doesn’t really care about the platform.” She is disappointed that tea party groups have to “babysit” legislators to make certain they follow the party.

There are several wild cards going into next year’s elections—Democratic discontent over the 2016 presidential outcome, President Trump and the Russia investigation, and uncertainty over whether the Texas sanctuary cities law will inspire a new wave of Hispanic voters to turn out. At present, however, the overall statewide outlook is for another scorched-earth series of Republican victories. But politicians need opponents to fire up their base. Democratic congressman Beto O’Rourke’s unabashed liberalism may yet serve that purpose in his challenge to incumbent U.S. Senator Ted Cruz. But if O’Rourke fails to become the Republican boogeyman, without President Obama on the ballot, Republicans are left without the usual suspects. McClatchy’s Washington news bureau reported earlier this summer that strategy already is being formulated by Republican consultants, and quoted one as saying, “Hillary Clinton is not on the ballot so you have to have something else to run against.”

Republicans seem to have a replacement in mind. In a discussion I had with former party chairman Mechler, he repeatedly brought up, without prompting, the idea that the news media is biased against Republicans. “I think the mainstream media is an extension of the Democratic party, and it’s always touting the party line,” he said. Mechler said he believes the media downplayed Trump’s recent visit to the Middle East to meet with the heads of numerous Muslim nations. “And if Obama had done that he would—they would have gone on and on. It’s absurd. What’s happening in the process of that? People ignore the media. They don’t trust the media.”

Media bashing and would-be Democratic candidates only get Republicans just so far. Still, they have each other as sparring partners. “There’s no way to accommodate everybody,” said McCarty. “And I hear that all the time—it’s all about unity, we’re all going to come together, we’re all going to work together. There’s no way. You have two completely opposite ideals. If we’ve got to find common ground then you’re giving up on what you truly believe in. So I think the momentum is in favor of the conservatives because that’s where you have your most passionate activists. So there are a lot of people that are still establishment GOP, but our numbers are growing—the conservative numbers are growing—and theirs are not.”