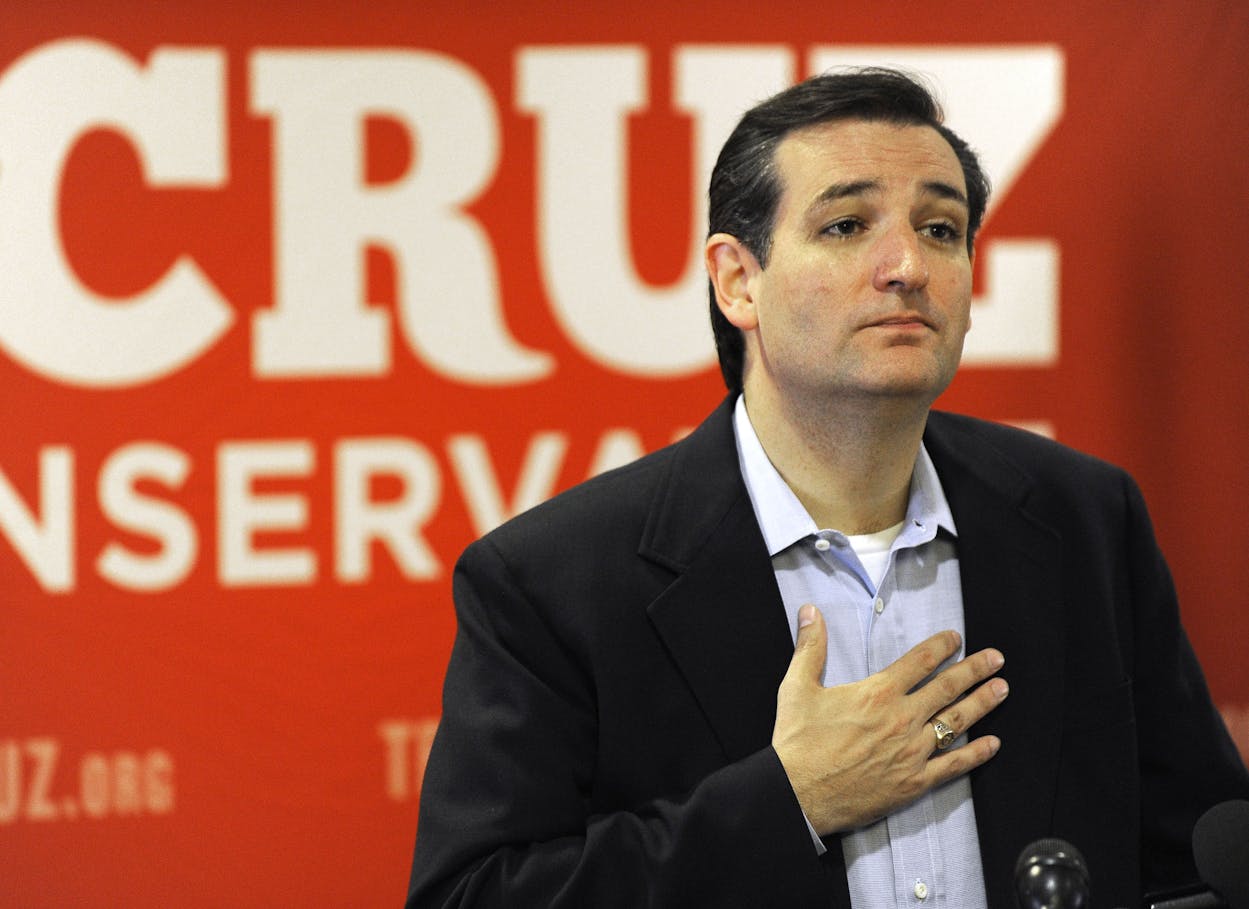

Over the weekend George W. Bush spoke at a fundraiser, held in Colorado, for his brother Jeb’s presidential campaign. The event was private, but Politico’s Eli Stokols asked around, and turned up something interesting. Bush is supporting his brother’s bid for the Republican presidential nomination, obviously, and he was mostly temperate in his comments about Jeb’s rivals. There was one exception, though; the second president Bush doesn’t have a good impression of his one-time employee, Texas’s junior senator, Ted Cruz:

“I just don’t like the guy,” Bush said Sunday night, according to conversations with more than half a dozen donors who attended the event.

A candidate’s “likeability” is hard to quantify. The closest proxy we have, I guess, would be favorability, and if you look at those tracking polls, Cruz’s numbers are seemingly unremarkable. The most recent results show that 28 percent of people have a favorable impression of him, and 43 percent see him in an unfavorable light; Jeb Bush, Rick Perry, Rand Paul, and Donald Trump all have a similar favorability gap.

But asking whether you have an unfavorable impression of someone isn’t the same as whether you like them; the former question is about your thoughts and the latter is about your feelings. Bush’s judgment of Cruz–I just don’t like the guy–is an essentially visceral assessment. In that sense, the comment doesn’t really tell us much about Cruz. It just reminds us of what we already knew about Bush, a man who often invoked his “gut” or “instinct” in making executive decisions during his years in public office, who could be stubbornly resolute in the face of contrary evidence, and whose more complex feelings about himself and his family were more often expressed in behavior than articulated in words. Those are very human traits on Bush’s part, though, and as far as I can tell, a lot of people share his feelings on the subject in question. And so Bush’s comments over the weekend do highlight a potential problem for Cruz’s candidacy, a deceptively obvious liability that Bush summarized well: A lot of people just don’t like the guy.

Readers who agree with the sentiment may consider this liability to be glaringly obvious rather than deceptively so, and I suspect that quite a few readers are in that camp. Since Cruz was first elected to the United States Senate in 2012, I’ve heard more people than I can count express the same kind of aversion that Bush did over the weekend. I’ve heard it so often that I think it has to be taken seriously, even though the feeling has consistently been reported without reference to a compelling explanation, and often without any stated reason at all.

While reporting Texas Monthly’s 2014 profile, for example, I talked to dozens of sources who had personal history with Cruz—these were conservatives, contemporaries, most of them Texans. Some of them did express a visceral distaste for the senator. But when I asked those sources to elaborate, none of them produced a concrete reason. They just disliked the guy. The only explanations offered were ex post facto and unconvincing.

Stokols’ story offers a useful example of what I mean. At the fundraiser, Bush went on to say that he finds Cruz’s alliance with Donald Trump, the Republican frontrunner, “opportunistic.” I agree, obviously. I’ve criticized Cruz for cozying up to Trump several times. At the same time I’d also say it’s opportunistic to gossip about the parentage of a rival’s adopted child, to dispute another rival’s military service, or to promote ballot initiatives on hot-button issues that in the hopes of boosting swing-state turnout during an election year, without regard for how the results might affect thousands of regular people for years to come.

And though Bush and Cruz may have had their private disputes, the public record suggests that if either of the two has occasion to resent the other, it would be Cruz. He was part of the legal team that put Bush in the White House in 2000, only to be rewarded with an obscure position at the Federal Trade Commission, only to be further rewarded, in 2012, by the widespread perception among the Texas grassroots that he was a paid-up crony of the big-spending George W. Bush. It’s true that as Texas’s solicitor general Cruz argued Medellin v Texas at the Supreme Court, and that the state’s victory came at the expense of the Bush administration. It’s also true that he won the approval of George H. W. Bush at some point, thus furthering the tension between himself and Karl Rove. Neither feat, I think, was fundamentally motivated by a desire to undermine George W. Bush; I can’t recall an example of Cruz directly undermining his former boss. His statement in response to Stokols’ story was gracious, considering that Bush basically handed Cruz an opening to take a swing at Jeb and shore up his outsider credentials: “I have great respect for George W. Bush, and was proud to work on his 2000 campaign and in his administration. … I met my wife Heidi working on his campaign, and so I will always be grateful to him.”

Cruz himself has acknowledged the seemingly disproportionate disdain he elicits from his critics, but I’m not sure any of them have softened in response. They may see such comments as self-valorizing rather than self-deprecating, since Cruz has also said that he’s “reviled in Washington” but appreciated back home, implying that his unpopularity is due to his stalwart commitment to principles. In any case, Bush’s criticism of Cruz is a reminder that feelings exist independently of reasons, and that while the latter may be invoked to substantiate the former, it’s rarely the other way around. So it’s of little practical consequence whether Bush’s instinctive aversion to Cruz is well founded or justified. The more important question is how many voters, fairly or not, feel the same way.