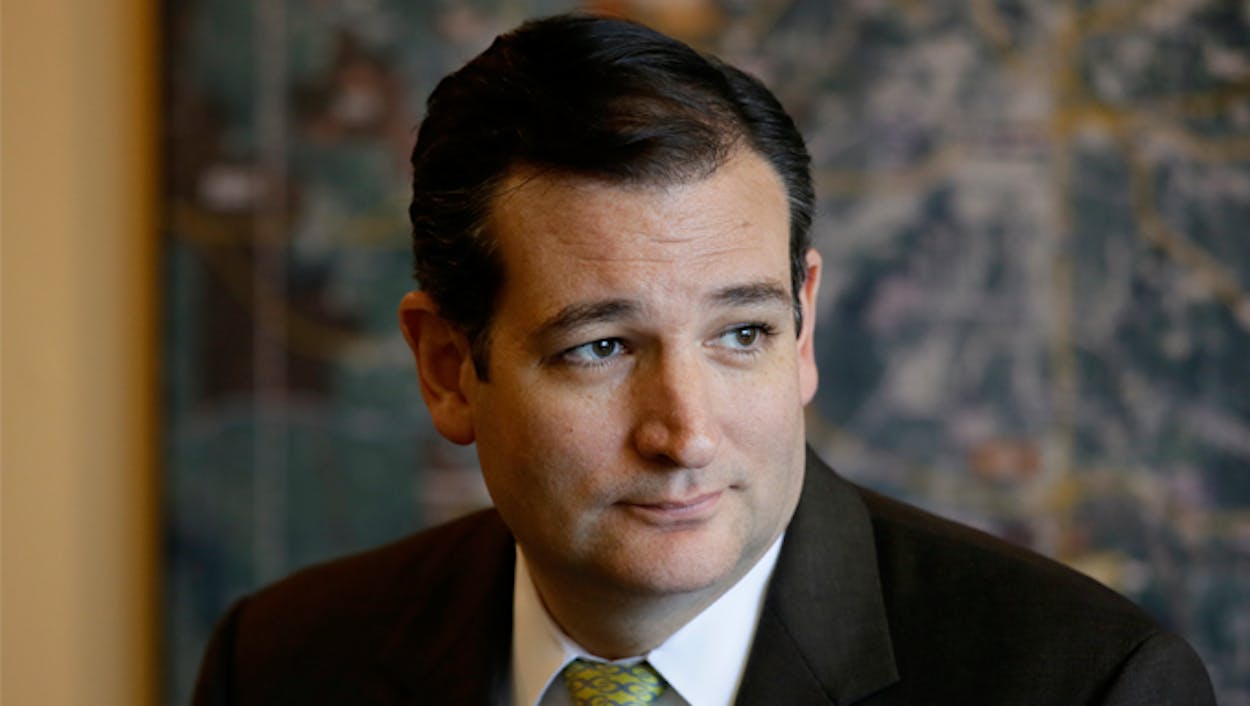

Even before the 2016 presidential election cycle began, most observers expected the race for the Republican nomination to be a war of attrition—especially compared to the Democratic primary, where Hillary Clinton was expected to enter the race as a nearly prohibitive frontrunner. And so back in March, when Ted Cruz announced his campaign for president, it was easy to infer that Texas’s junior senator would be planning for a long campaign that would leave him as the last candidate standing at the end of the GOP nomination fight. Cruz is shrewd. He wouldn’t have launched a campaign if he couldn’t see a path to victory.

And, for Cruz, the path wasn’t that hard to see. As I wrote then, the early polls didn’t seem auspicious: perhaps 4 percent of primary voters considered him their first choice, and Cruz was not the only candidate likely to compete as a conservative alternative to the party establishment. But several years of Republican infighting in Texas have already shown me that conservatives who oppose the establishment are united by their opposition, not their conservatism. The “Tea Party” is an umbrella term for a number of right-wing factions, which align on certain issues but are philosophically at odds on others. Cruz, unlike any of his likely rivals, had already navigated that tricky terrain, and therefore had a unique advantage. He might not be the first choice for pro-life voters, or for libertarians, but he could easily be the second: Rick Santorum endorsed him in his contested 2012 primary, as did Rand Paul. If he could outlast those candidates, he could have a good chance of rolling up their supporters along the way.

As I wrote in August, Cruz’s strategy became more complicated when Donald Trump barreled into the race and started throwing a temper tantrum, which has now been going on for months. As I noted last month, the strategy had shifted slightly, apparently in response to Trump’s continued popularity: Cruz had started offering occasional criticisms of unnamed “campaign conservatives,” rather than commending Trump while waiting for him to implode, as he had been doing. I continue to think that Cruz’s decision to cozy up to Trump was shockingly risky, in part because it was such a blatantly political calculation and in part because Trump remains the frontrunner, and his well-coddled supporters are comically defensive of their man. Last week, Cruz said that he doesn’t think Trump will be the nominee, and added that he, Cruz, plans to win “the lion’s share” of Trump’s supporters. As you can see in the comments section of the Breitbart story about the incident, many of Trump’s fans were outraged and aggrieved, as if they were somehow under the impression that Cruz, a United States senator who is running for the Republican presidential nomination, is trawling around Iowa looking for a chance to sacrifice his career on this golden altar.

In case there was any doubt, though, Cruz’s stated plans to roll up Trump’s supporters are explicit confirmation of his strategy. The Republican Liberty Caucus straw poll, held this weekend in New Hampshire, brought further confirmation that this is a shrewd strategy. The straw poll included 800 respondents who self-identify as libertarians or members of the Republican Party’s “liberty” wing, and used a methodology called “approval voting”: respondents were asked to name all the candidates they would vote for, rather than just one. Rand Paul won; 57 percent of the straw pollees said that they would vote for him. But Cruz had almost as much support: 51 percent said they would vote for him too. There was a steep drop-off for third place: just 17 percent of the liberty lovers who took part in the weekend’s proceedings said they would vote for Ben Carson. Most of the other candidates registered barely any support at all.

Straw polls, by their nature, are not particularly rigorous. No one should put too much weight on the Republican Liberty Caucus’s straw poll in particular, because one of its implications is that libertarians are too fractious to play a decisive role in presidential elections: Paul is clearly aligned with the libertarian wing of the party, and has made an assiduous effort to court libertarian Republicans, and yet he couldn’t win a supermajority of support among this self-selecting group of supposedly like-minded people.

More significant is that Paul didn’t even emerge from the straw poll as the dispositive leader of this faction. His campaign has been languishing anyway, and he doesn’t have an alternative base of support; if he can’t count on libertarian Republicans, he’s got no base that can keep him alive deep into the primary calendar. Conversely, the Republican Liberty Caucus’s straw poll is great news for Cruz. It’s a clear signal that he can plan on rolling up the lion’s share of Paul’s supporters at some point, as he was no doubt planning to do.

It’s also a signal that we need a nickname for Cruz’s 2016 strategy, because he’s clearly in this campaign for the long haul, and I don’t want to have to summarize his plan every time I write about him. Since he’s a Texan, we could call it the Tumbleweed, but that metaphor would imply that Cruz doesn’t have a focused trajectory, much less an end game. A more apt metaphor comes from the Katamari video games. Cruz is quietly rolling a small, Velcro-covered ball through the campaign, amassing more and more supporters along the way, until sooner or later he may have a boulder big enough to roll right into the general election.