This story is from Texas Monthly’s archives. We have left the text as it was originally published to maintain a clear historical record. Read more here about our archive digitization project.

Until recently, African Americans have largely been absent from Texas’ photographic history. Few scholarly texts on photography mention black Texans in the field, and few Texas museums have cataloged or displayed their work. Over the years, of course, African American Texans have appeared as the subjects of photos in selected settings: Formal nineteenth-century portraits were shot by white commercial photographers, for example, and Depression-era pictures were taken by white government photographers chronicling the extent of poverty in the United States. Yet these images, particularly the later ones, present an extreme view of Texas’ African American community, and they contribute to the grim stereotype of black life that persists today. They certainly don’t tell the whole story.

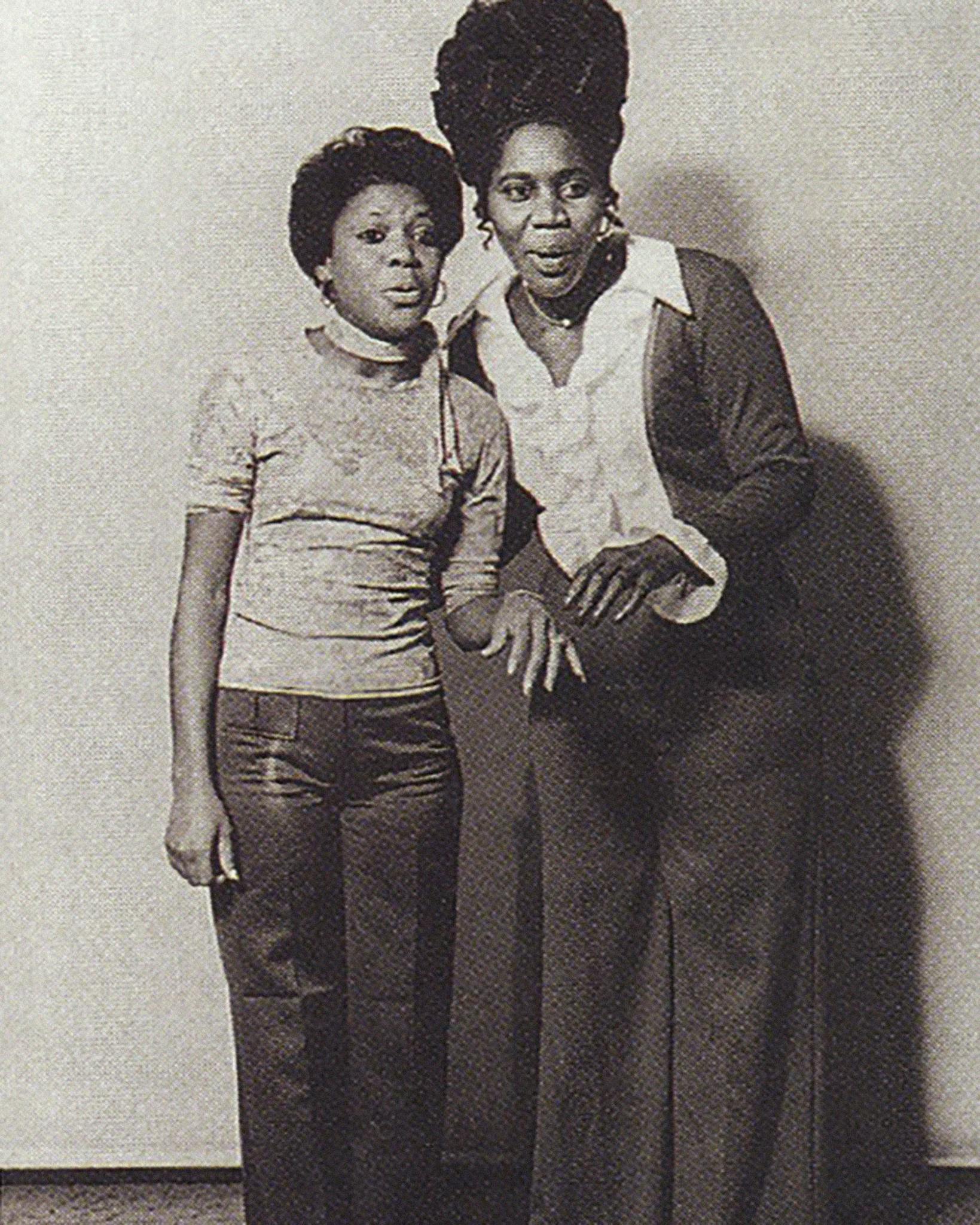

Alan Govenar hopes to change all that. This month the white folklorist is mounting an exhibit of photographs shot by little-known African American Texans from the 1870’s to the present. ‘‘Portraits of Community: African American Photography in Texas,” which is sponsored by Govenar’s nonprofit group, Documentary Arts, Inc., runs through January 21 at 5501 Columbia, the Dallas gallery he co-owns with his wife, Kaleta Doolin. It is a window on a world that has been mostly undocumented. The photographs are modest depictions of simple events: a birth, a graduation, a parade, a wedding, a death. There are young girls on a picnic, businessmen picketing for civil rights. The photographers don’t have a political or social agenda; they appear to be saying, “This is what I saw.” Taken together, however, the images have an unmistakable impact.

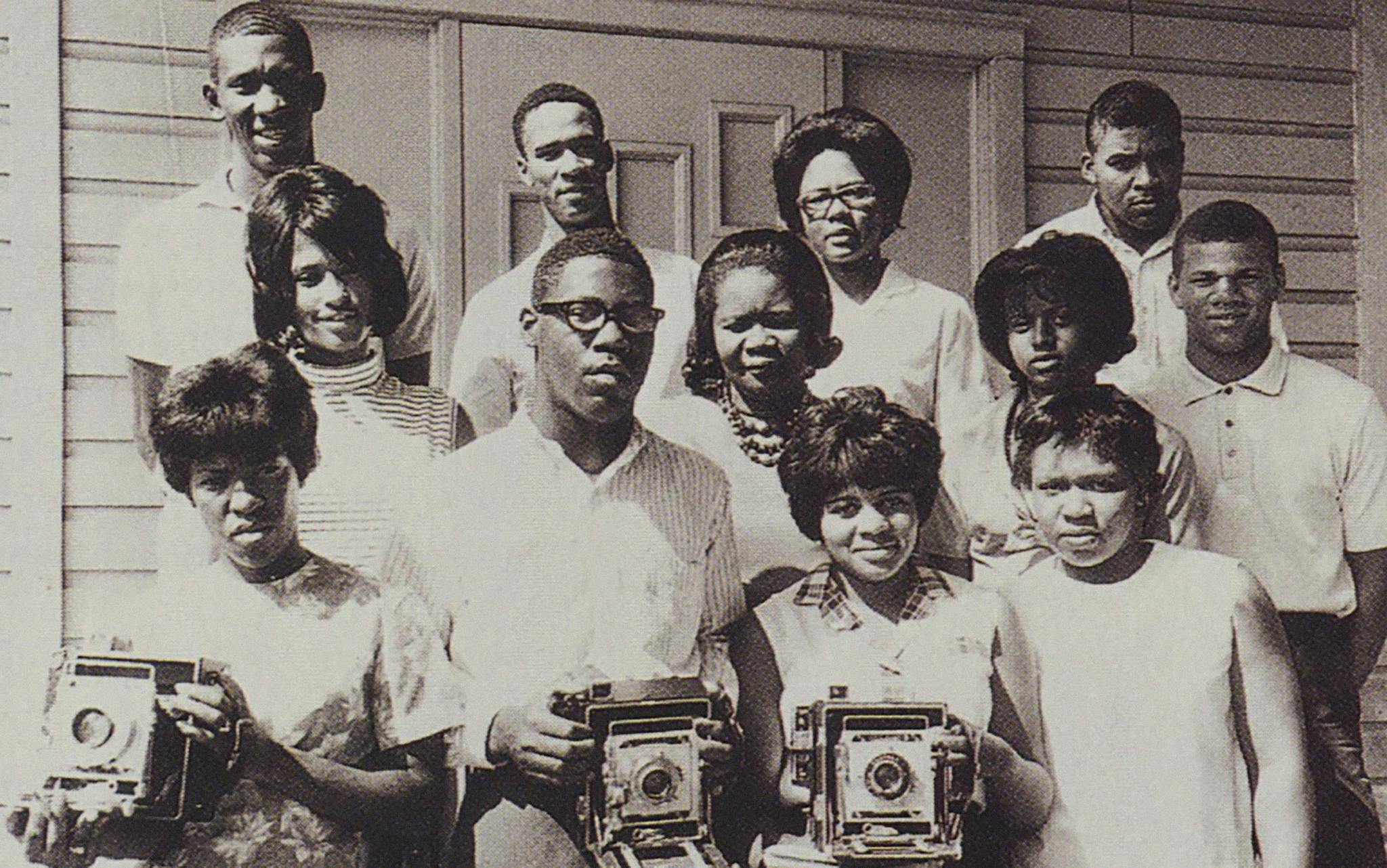

What is most striking about them is the sense of stability they convey. A mother and daughter dress up for Sunday afternoon tea; a photography class at Texas Southern University poses for a group shot, girls in crisp shirts, boys in slacks; debutantes preen in their gowns. “Physical dignity was especially important during the period of segregation,” TSU art historian Alvia Wardlaw has said. The quiet refinement of the community is remarkable when you consider that the memory of Texas’ last lynchings (in the thirties) was still fresh and that separate-but-equal was still an unhappy reality. “We put forth our best—even in clothes,” says seventy-year-old Dallas photographer Marion Butts, whose work is on display in the exhibit.

Govenar discovered Butts and the other contributors to “Portraits of Community” beginning in 1984, while researching The Early Years of Rhythm and Blues, a book of photos of Texas blues artists by Benny Joseph, a sometime photographer for Houston blues label Peacock Records. After rescuing thousands of negatives from Joseph’s studio, Govenar searched for other overlooked African Americans and their unseen work. To date he has found the works of 45 men and women who had been commercial photographers or photography teachers in Texas. Many were students of A. C. Teal, the charismatic black entrepreneur who founded the Teal School of Photography at Houston Negro College (now TSU) in the forties. “Being a photographer was a respectable way for a black man or woman to make a living on their own,” says seventy-year-old Elnora Frazier of Houston, who was a member of Teal’s first graduating class. Churches, schools, and families all wanted snapshots of their daily doings, from the momentous to the mundane. As the African American newspaper Houston Informer wrote in 1942, photography was “a field where there is a dire need of workers and plenty of space to work.”

Govenar, who runs Documentary Arts out of a remodeled fire station in a mixed neighborhood in East Dallas, says he wants to bring art to the African American community and preserve dying art forms. So far, he has had some success. Teal, a well-regarded photographer who died in 1956, has only a dozen early portraits in the exhibit: a Teal School graduation announcement that Frazier saved, and a few photographs owned by the Houston Public Library. The rest of his work hasn’t turned up. “I hope someone will see this show and realize that they’ve got this stuff in their attic,” Govenar says. He had somewhat better luck with Frazier, whose distinctive hand-tinting comes across in portraits of her daughter and of an elderly couple. She had thrown half her negatives away before Govenar tracked her down. “I wasn’t viewing what I did as art,” she says. Govenar did manage to preserve all the work of 87-year-old Curtis Humphrey, whose ramshackle studio sits on Tyler’s west side: Humphrey was considering selling his negatives for their silver content.

That the importance of these photos escaped scholars and curators alike may be one of the last vestiges of segregation. “ ‘Portraits of Community’ shows that these people existed in a way most of us never suspected,” says Fort Worth Star-Telegram columnist Bob Ray Sanders, who sits on the board of Documentary Arts. “Here is a picture of the emerging middle class: teachers, preachers, lawyers, and leaders. Here is the black community the way it wanted to be preserved.”

For a complete exhibit schedule, call 214-823-8955.

- More About:

- Art

- TM Classics

- Photo Essay

- Dallas