He was a small child, not yet four, and so the floorboards did not betray his movements as he slipped out from under his blankets, walked past the bed where his twin brother slept, and headed down the dark hallway. His parents were out for the evening, while the baby-sitter, his half brother, was somewhere downstairs, preoccupied with a girlfriend. The boy’s other siblings were asleep. No one heard him enter the bathroom and climb atop the stool in front of the sink. No one heard the stool give way and the child fall, his head colliding against the tile floor. The boy suffered from a form of hemophilia; by the time they had taken him to the hospital, he had already bled all there was to bleed. A few days later, they buried him in a family plot just west of downtown Corpus Christi, under a simple marker that read: “Vincent Bluntzer Tarlton Farenthold. February 8, 1956–January 26, 1960.”

The funeral was an agonizing experience for the boy’s mother, 33-year-old Frances “Sissy” Tarlton Farenthold, and all the more so because the tragedy brought her face to face with an image from her childhood that reared up to haunt her now and again. The recurring image was that of another dead three-year-old boy: her brother Benjamin Dudley “Sonny” Tarlton III, who had died from complications following surgery to remove a quarter he had swallowed. When her great-aunt Mary hoisted the then two-year-old Sissy up to view her brother stretched out in the casket, the little girl beheld the old women sobbing all around her, then looked down at the boy’s motionless body. All she could think was: Why won’t Sonny get up?

Sissy Farenthold would never forget that feeling of bewilderment. She would remember her mother’s reclusiveness, remember her snapping up all of the pictures of Sonny and putting them away where they would never be seen again. She would remember her father, a towering and mirthful man, and how he commemorated his eldest child’s passing by spending each May in a state of weeping depression. Recalling the tragedy of her childhood years, Sissy Farenthold resolved two things following the death of her son. First, she would not become a captive of grief. She would move forward from Vincent’s death, throwing herself at one challenge and then the next—a crusade of diversion that became another crusade entirely, one from which Sissy Farenthold emerged as the state’s best-known liberal politician and one of the nation’s most prominent feminists.

By comparison, her second decision seemed uneventful though just as heartfelt. Recalling how the image of her brother in the casket had stayed with her, Sissy Farenthold decided that her youngest child, Jimmy, Vincent’s identical twin, should not attend the funeral with the rest of the family.

It was one of those parental judgment calls for which no one could possibly fault the mother—no one, that is, but Jimmy, who in later years would speak remorsefully of not having had the chance to say good-bye to his brother. Jimmy never volunteered this sentiment to Sissy. She found out during a conversation with one of her son’s many drug counselors, and by that time all the damage had been done: His life, like hers, had taken a decisive turn upon Vincent’s death. Both mother and son pursued their destinies with seemingly unstoppable momentum. But while Sissy bulldozed her way into the heart of the political arena, her youngest child lunged toward the edge, beyond which his twin awaited him.

Three years ago this month, 33-year-old Jimmy Farenthold vanished. Not a soul has heard from him since. Policemen, detectives, friends, and family have spent the intervening period poring over clues but have nothing to show for their efforts. The hopeful few who believe that Jimmy has simply gone underground so as to elude the expectations of his family cannot explain why he would also have broken off contact with all of his close friends. Virtually everyone who knew Jimmy and the dangerous life he led suspects that he is dead. Yet no body has been found. It is as if the surviving twin had never existed.

What befell Jimmy has become a matter of wild speculation, except that it is generally accepted that whatever happened to him did not happen randomly. Rather, it happened to Jimmy Farenthold because of who he is: the doomed runt of a great but precarious brood, heir to all of its curses. His disappearance is only the latest installment of a larger tragedy, one that has plagued a prominent family for generations. Quietly, very quietly, it has ravaged what might otherwise have been a kind of dynasty. Evidently Jimmy’s fate was to join the fallen, just as his mother’s lot in life has been to survive, ascend, and then, from a lone vantage point, ponder the devastation of her kin.

I USED TO POINT TO THE WHITE STRANDS in my hair and say to him, ‘See where it’s white, Jimmy? That’s from you.’” Sissy Farenthold’s voice fades to a murmur as she unconsciously runs her fingers through her hair, which is now completely white. “It didn’t mean I didn’t love him.” She manages a smile. “And today, if Jimmy would walk in, he had such a personality that he’d have us laughing and feeling good. He had that, that sense of the ridiculous. He was that way… .”

For a moment she dares to think hopefully of her son. Then Sissy Farenthold bows her head and tightly closes her eyes. Today is one of those days when it is best to avoid encounters with strangers: Grief has the final say in every given moment, and one’s very resolve seems awash in tears. It is February 8, 1992. Vincent would be 36 today, had he not bled to death. Today is Jimmy’s birthday as well, and if he is alive, then surely he is celebrating the event by sleeping in until, say, mid-afternoon and in the evening doing things up in high style, throwing wads of cash at the bartender, and buying a few rounds for newfound friends, his sweetly fiendish face locked in a state of glee. It is a pretty thought, but today pretty thoughts only invite more anguish. Her experience tells her to fear the worst. She speaks of him in the past tense.

“He took chances,” she says. “He took chances all the time. You know, he was a very sweet person. Charming too, but more basic than the charm was that he was very sensitive. He could be hurt. The Vincent thing had been so painful that I probably didn’t talk about it to him as openly as would have been helpful. But I thought I was shielding him. Just like when I moved him into a different bedroom. You know, you’re just feeling your way—there are no rules.”

She slumps against the back of the couch in the living room of her Houston high-rise apartment and stares furiously at her clasped hands. For whatever else 65-year-old Sissy Farenthold might be, at this moment she is a grieving mother, small and alone and powerless. The posture does not become her, for Farenthold is not the self-pitying sort. The days of cleaning up the Texas Legislature and mounting a quixotic campaign for governor are two decades behind her, but her activist barnstorming continues. These days she travels from Washington to Brownsville all in the same week, lobbying for progressive causes, picketing missile bases, spearheading think tanks on federal government reform. As a speaker she remains in high demand: This very morning, a Saturday, she addressed a delegation of high school students at a United Nations Model Congress.

In her discreetly fashionable dress and black stockings, her feathery white hair lending a light touch to her morose and narrow face, Sissy Farenthold cuts an elegant figure of almost brutal composure. Evidence of her age is strictly physical—and for that matter she wears her years well, insofar as her older face reveals the essence of the woman in a way the more youthful face never did. Now her determination and intensity of belief are highlighted by wrinkles that are impossible to miss, just as her battles against corrupt institutions are a matter of public record. Yet it has remained a matter of mystery that both her face and her crusades have always betrayed a complete absence of joy. For all of Farenthold’s public life, reporters have observed her gloomy aura without knowing what to make of it. “A melancholy rebel,” the Texas Observer tagged her; “She seems to have a great capacity for inner sorrow,” wrote author Myra MacPherson. In the heat of the fight, Farenthold could be heard bemoaning the cruel conditions—corruption, bureaucratic insensitivity—that made the fight necessary; with triumph in her grasp, she would ruminate on the price of success. Hers was, and still is, the quintessential bleeding heart.

All of the moods and themes that preoccupy Sissy Farenthold can be traced to her family, which has played a visible role in Texas history for well over a century. Her Alsatian great-great-grandfather, Peter Bluntzer, brought forty families to settle the South Texas county of DeWitt in 1843. Her Irish great-grandfather, Robert Dougherty, helped settle San Patricio and founded the first boys’ academy in South Texas. Great-grandfather Nicholas Bluntzer, a Nueces County pioneer, served as Robert E. Lee’s scout during pre–Civil War punitive expeditions against the Comanches. Her paternal grandfather, Benjamin Dudley Tarlton, Sr., spent several years as chief justice on the state’s highest court before becoming a professor at the University of Texas School of Law, whose library bears his name.

The Bluntzer-Dougherty-Tarlton-Farenthold family tree abounds with all the requisite characters for a Texas dynasty: Civil War officers, oil and cattle men, lawyers, and landholders. Substantial wealth remains in part of the family, and the surnames retain a certain cachet. But three features distinguish Sissy Farenthold’s clan from others that sprawl across Texas. First, it is a family in which women have never quavered in the shadow of their husbands. Lida Dougherty, Farenthold’s great-aunt, was the first woman in Texas to become the superintendent of a school district. Farenthold’s aunt Genevieve Tarlton Dougherty, a well-known philanthropist, was conferred the Lady of the Grand Cross of the Holy Sepulchre by Pope Pius XII, one of the highest honors the Catholic church accords a laywoman. Other female antecedents were educators and community leaders; there was even one adventurer of sorts, Farenthold’s great-great-aunt Theresa Bluntzer Hasdorff, who at the age of four was kidnapped by Indians and returned a year later, decked out in native headdress, speaking the tongue of her captors.

Perhaps not surprisingly in a family of such strong female figures, Farenthold’s kin have also stood prominently to the left of the state’s most famous families. Her father was a Klan-baiting lawyer and lifelong Democratic activist. While other Texans were admonishing their children at the dinner table, “Think of the starving children,” Farenthold’s relatives were donating enormous sums of money to feed Biafran and Mexican orphans.

There is a third aspect to this great family, a feature more often associated with the characters in William Faulkner novels than with real people. Beneath the public facade, the prim liberal sheen, lurks a disquiet—perhaps genetic in nature, perhaps owing to a series of unfortunate coincidences. But it has endured through generations, spreading across the Bluntzer-Dougherty-Tarlton-Farenthold family tree like an unseen fungus. It has given rise to alcoholism, drug addiction, and manic depression. It has saddled descendants with disorders ranging from the mildly disabling to the fatal. Still others have fallen to diseases such as cancer, and others still have died freakishly—shot with their own hunting rifle, drowned in their own swimming pool. Rustling within Sissy Farenthold’s family is a severe capacity for self-destruction.

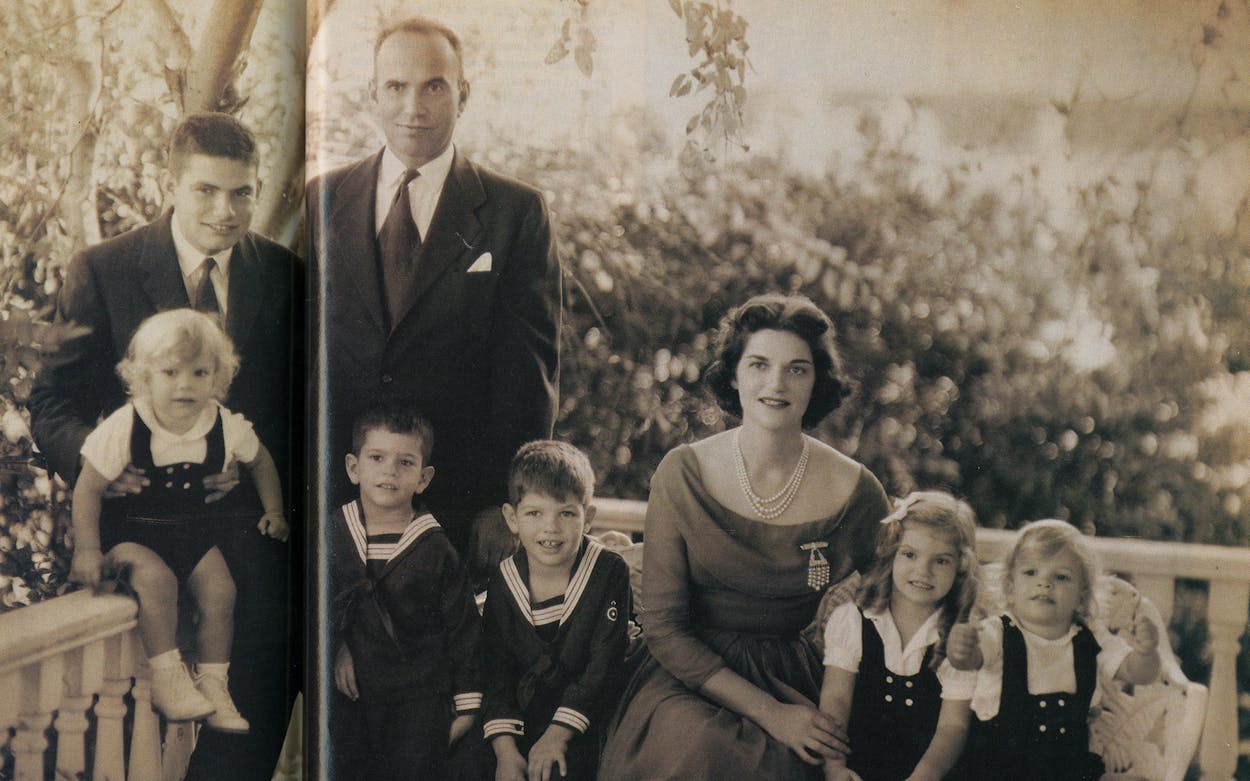

IN 1950, 24-YEAR-OLD VASSAR COLLEGE and UT law graduate Frances “Sissy” Tarlton was wedded in a Corpus Christi Catholic cathedral to George Edward Farenthold, a furry-browed, bull-bodied Belgian who had received his U.S. citizenship in 1940 and subsequently became a decorated Air Force captain. The great-grandson of a prosperous inventor, George was a man accustomed to high living, which included making a home in what is now the official residence of the president of Algeria, getting his education in a Swiss academy, and enjoying the company of a manservant wherever he traveled. His first marriage to a Texas woman had been a bust, ending in 1948, but not before George had availed himself of his wealthy father-in-law’s business knowledge and capitalized on a few lucrative opportunities. Thus he came to the Bluntzer-Dougherty-Tarlton family, bringing with him an internationalist’s savoir-vivre, a good head for the oil business, a ten-year-old son named Randolph by his previous marriage, and the rich bloodlines of Belgian aristocracy.

Yet there was a peculiarity to the Farenthold blood: It did not readily coagulate. Belgian doctors had diagnosed the syndrome as “pseudo-hemophilia,” less serious than the classic condition, though still resulting in excessive bleeding. Indeed, George’s aunt had bled to death during menstruation, just as George himself had suffered a near-fatal blood loss when his tonsils were removed. But he managed to live with the condition, dutifully rushing off to the hospital to get sewn up after every ice hockey accident. The pseudo-hemophilia was not a marital issue for George and Sissy. And since his son, Randolph, did not seem to be a free-bleeder, the newlyweds fearlessly embarked on having children: Dudley in 1951, George Junior in 1952, Emilie in 1954, and the twins in 1956—first Vincent and then, a minute later, Jimmy.

None of the Farentholds can recall exactly when it became apparent that the offspring had inherited their father’s condition. Instead it seems that the discovery fell on them like the family plague it was. “My children bled and bled and bled,” Sissy Farenthold says of the routine childhood mishaps that escalated into emergency-room episodes. After consulting with doctors at Houston’s Texas Children’s Hospital, the Farentholds learned that George and his children—minus his two eldest children, Randolph by the first marriage and Dudley by Sissy—suffered from von Willebrand’s Disease, a hereditary bleeding disorder caused by a deficiency in the clotting agent factor VIII. The disease had no cure; the family would learn to live with it and pray that fate would show clemency. Then Vincent fell.

“FOR YEARS AFTER THAT, IF I heard a child cry, it would just tear me up,” recalls Sissy Farenthold. But at her husband’s urging, she fought to turn away from her pain. The natural avenue was politics. As a child, she had been dragged to county elections by her yellow-dog Democrat father, who exhorted her to memorize the names of every Corpus Christi city council member. Throughout the early years of her marriage, she carried on the family’s Democratic traditions. Now politics became her obsession, the path away from malaise.

Yet she could not bring herself to desert Jimmy, who seemed lost without his brother. The twins had been inseparable; even when placed in separate cribs, they would talk to each other across the room in a language no one else understood. “They didn’t have the sense of needing parents,” says Sissy. The bond was intense, and so was the sudden disconnection. For at least a year following Vincent’s death, the surviving twin would run for the screen door every time he heard it slam, expecting to see Vincent in the doorway.

And so as Sissy began her foray into politics, she took the baby of the family wherever she went—to city council meetings, to campaign rallies. So concerned was she that a bloody fate would claim her son that she persuaded other mothers at Jimmy’s school to lobby for improvements in the playground’s safety standards. It was Sissy Farenthold’s first attempt at political organizing.

In many ways, Jimmy seemed fine. He was sweet and generous by nature, loved pets and plants, and often wandered through crowds, striking up conversations with total strangers. But the tendency to stray from her side disturbed Sissy, for the boy possessed a heedless, unanchored quality, a tendency to leap before looking. At times this was literally true. Before becoming a proficient swimmer, Jimmy could not resist the urge to dive into a pool and thereby sink right to the bottom, causing lifeguards and parents to scurry after him. All the Farenthold children were schooled in the hazards of von Willebrand’s Disease, but Jimmy continued to take risks and spill blood. “I was very careful,” his mother sighs. “But he was a daredevil.”

In time, her fears gave way to new preoccupations. Sissy became active in the John F. Kennedy presidential campaign, helped coordinate her cousin Dudley Dougherty’s unsuccessful congressional race, and in 1965 became the director of legal aid for Nueces County. In that position she saw, for the first time in her pampered life, the horrors of poverty and the government’s apparent indifference to human suffering. Her passions grew even as her sadness mounted.

Still, when a family friend persuaded Sissy to run for the Texas House of Representatives in 1968, no one who knew her could have sized her up as a natural politician. For all her intellect and liberal convictions, she was a painfully shy person. When the campaign began, the new candidate could not bring herself to approach voters on the street. Finally, George dropped her off in a crowded shopping center parking lot one afternoon, handed her a stack of 1,500 campaign brochures and a dime, and told his wife, “When you’ve given all these out, call me and I’ll come get you.” Then he drove off and left her there.

She would later refer to that first campaign as “unbelievable torment.” But the family tragedies that made a pessimist out of Sissy Farenthold also made her tough. Sonny’s death had all but incapacitated Sissy’s mother, leaving Sissy to manage many of the household matters. Although Sissy showed signs of dyslexia—she could not read until she was almost ten—she willed herself to graduate from Vassar and later made the dean’s list at UT law, where she was one of only four female students in her class. Thus steeled by death and doubters, 42-year-old Frances Tarlton Farenthold again overcame her handicaps, and in November 1968, she became the first woman ever to represent Nueces and Kleberg counties in the Legislature.

The 1969 House roster consisted of 149 males and Sissy Farenthold. Unlike her sole female counterpart in the Senate, Barbara Jordan—who took pains not to ruffle conservative feathers while she prepared for a U.S. House candidacy—Farenthold refused to play it safe. She stood alone in her opposition to a 1969 resolution commending the performance of former president Lyndon Johnson. When she found herself locked out of House Constitutional Amendments Committee meetings—which were held at Austin’s all-male Citadel Club—she did not sulk privately but rather took the matter to the media and forced a public apology from her colleagues.

In Farenthold’s mind, her own predicament as the token House female was reminiscent of the inequalities she had seen as legal aid director. There was a rottenness to the institutions themselves, a tendency to favor a few and exclude the rest. Reform became her passion, and by 1971 it made Sissy Farenthold a household name in Texas. That year, she and 29 disaffected House Republicans and liberal Democrats—“the Dirty Thirty”—crusaded against corruption in the Legislature, focusing on House Speaker Gus Mutscher, who was accused of conspiring to take bribes to pass bills benefiting powerful Houston banker and developer Frank Sharp. Mutscher’s subsequent conviction ended the so-called Sharps-town Scandal, but to Farenthold the reform movement was barely beginning.

In 1972, with the strong encouragement of her admirers and the approval of her family, the Dirty Thirty’s self-styled “den mother” set her sights on the Governor’s Mansion. Farenthold ran as a reform candidate, positioning herself against a corrupt system and contaminated opponents. She bumped off Governor Preston Smith and Lieutenant Governor Ben Barnes in the primary, when scandal-weary voters turned on incumbents, and trailed only Dolph Briscoe, a wealthy rancher. Briscoe won the primary runoff with 55 percent of the vote, but the defeat seemed to have no effect on Sissy Farenthold’s burgeoning celebrity. At the Democratic National Convention, she became the first woman ever nominated for vice president, receiving 407 delegate votes to finish second behind Thomas Eagleton. A few months later, she posed with Shirley Chisholm for the cover of Ms. magazine.

Sissy Farenthold had ascended, surpassing the feats of her forefathers. But all of her successes could not prevent her offspring from repeating the ritual descent of their ancestry.

THOUGH SISSY FARENTHOLD BLAZED trails for women everywhere, none left scorch marks as deep and lasting as her struggle to balance her political and parental responsibilities. As the only female member of the Texas House, Farenthold was faced with a stark choice. She could either come running whenever her children needed her and thereby suffer the derision of her male colleagues, who already guffawed whenever she spoke of the deep influence her children had on her thinking, or she could vow never to miss a vote or a committee meeting and thus be taken seriously but face serious consequences at home. As a candidate for governor, she could stay at home with the children and ensure her defeat, or she could take them on the campaign trail with her and hope that they would be able to bear the limelight. As was the way of the world in 1972, the father was exempted from the child-rearing equation. George had his pipeline business to attend to, and indeed a family of six could not scrape by on a state representative’s income.

Sissy Farenthold’s choice to be a serious politician took its toll subtly at first. Two of the children shared Sissy’s reading disorder and needed more help with their schoolwork than she could give. Jimmy’s dyslexia was most acute, and with Sissy no longer nearby to keep his fondness for wandering in check, it became a familiar sight to behold the youngest Farenthold, frail and dark-haired and grinning as he wandered the streets of Austin, a pre-teen urchin in search of who could say what.

When Sissy ran for governor in 1972, she did so with Dudley, George Junior, and Emilie in tow. The three were enthusiastic campaigners and even cut their long hair so as not to be a political liability; yet they were also of college age, and all of them had dropped out to assist their mother. Meanwhile, sixteen-year-old Jimmy was deemed a troublemaker by the authorities at St. Stephen’s Episcopal School in Austin and prohibited from living on campus. Not knowing what else to do with her youngest during the campaign, Sissy sent him to live with her friends Liz and John Henry Faulk. Three days after Sissy’s loss to Briscoe in the runoff, the body of her stepson, George’s 32-year-old son, Randy, washed ashore on Mustang Island. Chains were wrapped around his chest, along with a forty-pound concrete block around his neck. Years later it would emerge that he had been murdered for threatening to testify against four individuals who had swindled him out of $100,000.

Randy had possessed little in the way of ambition or common sense, but he was roundly regarded as a good-hearted fellow. Sissy and her offspring had been close to Randy. His bizarre death recalled all the old family demons and cast a pall of vulnerability on the Farenthold household, which by nature was already fragile. The family members rotated residences in Austin, Houston, and Corpus Christi, with the father and mother almost always living apart after Sissy’s election. Sissy and George’s marriage, never terribly amorous to begin with, now seemed to be purely an accommodation. The children were feuding with their father and forsaking their education to bolster their mother’s career. Sissy Farenthold saw the family’s demise in glimpses. Privately she fretted to political aides and friends and at times to reporters. To one of the latter, she let the fatalism flow: “You try to hold on to the family thing,” she said, “and you probably fail.”

The family’s failure was spurred on, at least partly, by drugs. Its bloodlines had revealed a predisposition for alcohol dependence. Now the latest generation introduced narcotics as a new variation on the old malady. One of Sissy’s nephews, an addict, shot himself in the head on his twenty-first birthday. At least two other nephews were arrested for possession. Yet another nephew, whose use was legendary, according to a family member, openly flaunted his heroin stash in front of Sissy—though in the end his premature death was due to hepatitis, said to have been brought on by alcoholism.

By the time Sissy had mounted a second unsuccessful candidacy for governor in 1974 and later moved to upstate New York to become the first woman president of all-female Wells College, drugs were an issue in the Farenthold household. Each of the children, by virtue of their conspicuous last name, had fallen into the proximity of the young idle rich, many of whom spent the seventies blowing their trust funds on cocaine and heroin. “Speaking for myself and my family,” says Sissy Farenthold today, “maybe some people can use drugs, but there are some who can’t. My family has been ravaged by drugs, and I include alcohol in that.” Some of her children emerged from the high life relatively unscarred, but others did not. One of them eventually sought treatment for alcoholism; another underwent treatment for narcotics addiction.

The fate of the Farenthold children would not be to live up to the great family standard but rather to wrestle with the great family infirmities. In time, each of them would prevail—all but Jimmy, who seemed not to wrestle with the curses but instead to embrace them.

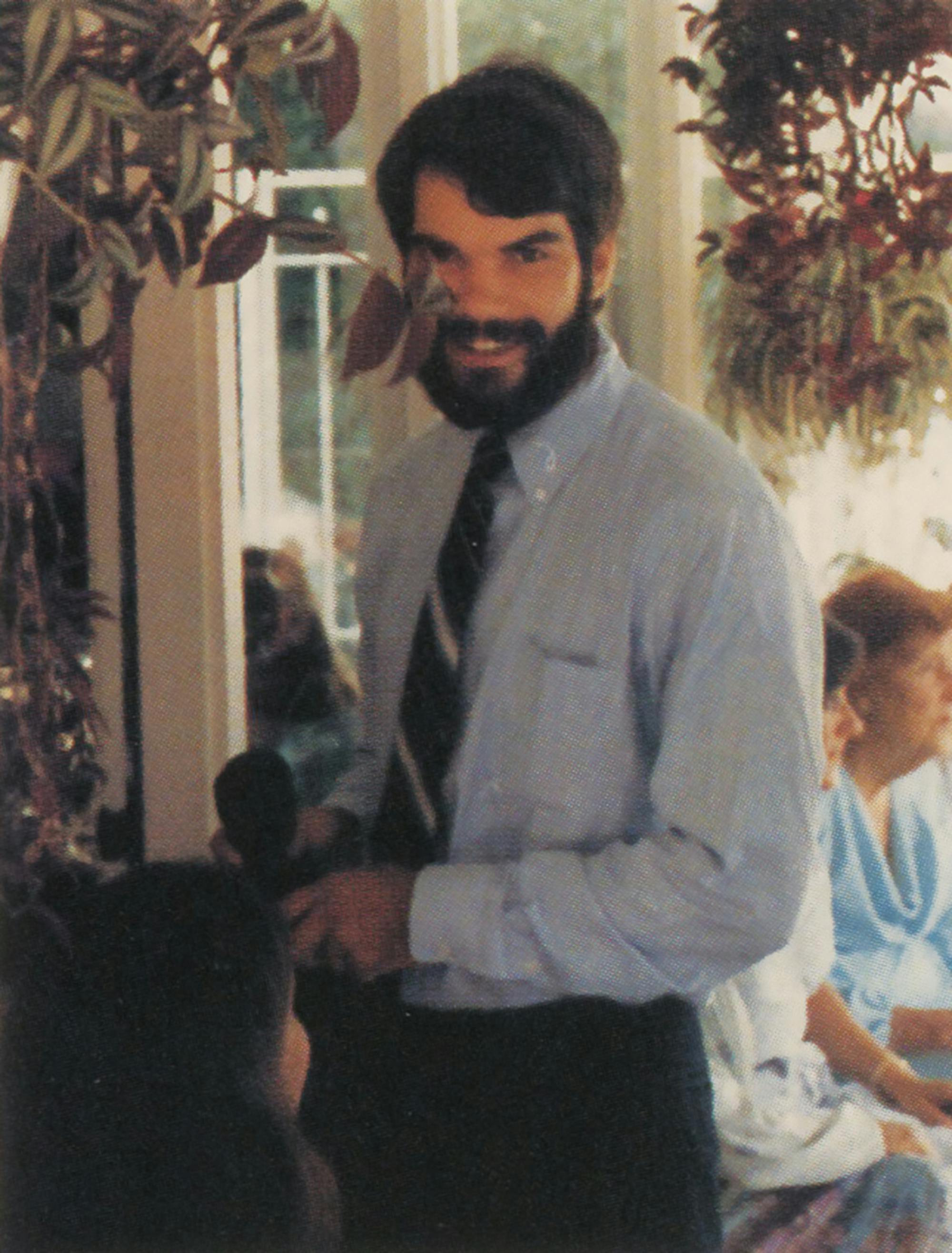

AT THE CLOSE OF THE SEVENTIES, while Sissy Farenthold and her three eldest children were vowing never to drink or take drugs, Jimmy was living by a different sort of vow: Never pass up a thrill. The boy daredevil was now a young man and more reckless than ever, a free-bleeder who routinely courted bloodshed. He drove his car and his motorcycle at madman speed, without benefit of seat belt or glasses, though his eyesight was poor. He was injured after a motorcycle accident and wound up in the hospital after being stabbed in the nose during a barroom brawl. At a topless bar he went after a biker’s girl and wound up in a nearby dumpster—bruised but miraculously not bloodied.

Jimmy hid these incidents from his mother, feeling that he was one continual heartbreak to her. When absolutely desperate—flat broke, strung out on cocaine—he came to Sissy. Otherwise Jimmy avoided his family, whose very presence would raise the specter of his failure to amount to anything. He ping-ponged about, staying with a buddy in Houston, a family friend in Fort Worth, a cousin in Austin, or an aunt in Corpus Christi, leaving full wardrobes in closets all over the state. Several couples who took Jimmy in found that they had become a surrogate family and were flattered but also saddened when he took to calling them Mom and Dad.

With feigned pride he would tell his friends, “I’m the black sheep.” Referring to the drug overdose of Robert Kennedy’s son, Jimmy observed, “Now that he is dead, he won’t be an embarrassment to the family. They won’t have to try to keep the lid on,” and then drew the parallel: “My family will do anything to keep me under wraps.” At times he did not conceal his hostility—and during those times, he spoke of his twin: about how the family would not let him attend his own brother’s funeral; about how they never talked about Vincent and simply went on with their lives. Now and again the surviving twin would say, more to himself than to anyone else, “The good one died.”

“I like the edge,” he once told his mother, referring to his cocaine-fueled lifestyle. But his addiction was all too apparent to her. Sissy took Jimmy to one expensive rehabilitation center and then the next. “I’m going, but only because you want me to,” he would tell her. Jimmy left a treatment center in Phoenix after the patients complained that he was making a mockery of the program; at other times he simply withdrew, complaining of the food or the clientele. On one occasion, after being driven to a halfway house by a friend of Sissy’s, Jimmy escaped that evening and caught a plane to Houston. He phoned the friend two weeks later, more or less apologizing. “I’ve been a bad boy,” he said.

IN THE EARLY DAYS OF APRIL 1989, Jimmy traveled to Houston and stayed with his mother for a couple of weeks. It had been a rough year so far for Jimmy, as Sissy well knew. He had been doing crack cocaine, and once she discovered him lying unconscious on a bed with drug paraphernalia strewn about him. But now he was attending Alcoholics Anonymous meetings, sometimes as many as four a day. One late night, while they strolled the streets of River Oaks, Jimmy told Sissy that he wanted to straighten his life out. He was really trying, he said. “But, Sis, it’s not one day at a time for me,” he admitted. “It’s one second at a time.”

He told her that a friend of his had successfully undergone drug treatment at a center in West Palm Beach. He would make all of the arrangements, if Sissy would put up the money. Jimmy’s earnestness impressed her; she said that she would. Jimmy booked a plane reservation for Monday, April 17, 1989.

Sissy was in Washington on April 17. After she returned and failed to hear from Jimmy, George Farenthold called the treatment center. They told him that Jimmy had not arrived. Sissy’s heart sank. Jimmy had duped her again. A few months later, Sissy got a refund for the unused Pan Am ticket. Sissy placed the receipt in a folder, next to a voucher representing a trip to Vienna Jimmy was supposed to have taken with her a few months before. He hadn’t made that flight either—he was in Corpus Christi at the time, doing crack with a friend.

“There had been times where he would be gone four, five, or six months, and we wouldn’t hear from him,” she says today. “So it was one of those things you might worry about—but it wasn’t unique.” Her concern began to mount after talking with those who had been close to Jimmy. A friend in Fort Worth had spoken to him by phone on the morning of April 14. Jimmy had told the friend that he had no intention of going to the Florida treatment center. Instead, he was going to San Antonio to visit his sister Emilie’s husband, Alan Stewart. For some time now, Alan had been holding on to a sum of money that he had indicated he might give to Jimmy for the purpose of starting a legitimate business, once Jimmy got straight. “When I get the money,” Jimmy told the friend, “I’m going to get some of my things, and I’m going to come up to Fort Worth, and I’m going to get a new place and a new car and a new job, and I’m going to have a new life.” To the friend, he sounded sincere. Yet she had not heard from him since.

Sissy spoke with her son-in-law, Alan Stewart. Alan told her that Jimmy had flown in to see him on April 16. He wanted money, and while Alan was loath to hand over a bundle of cash to a drug addict, he assured Jimmy that he and other family members would do all they could to set Jimmy up in some kind of legitimate business once he successfully completed drug treatment. It appeared to Alan that Jimmy’s commitment to getting straight was wavering: He was already worrying that the center might be too harsh, that he might need a car so that he wouldn’t feel imprisoned, that he might have to postpone his trip to attend to a few matters back in Corpus Christi. Still, he told his brother-in-law he intended to make it to Florida, and Alan dropped Jimmy off at the airport that afternoon, feeling no reason to doubt him.

A call came in from an Austin couple who had served as one of Jimmy’s surrogate families. They had been in fairly constant contact with Jimmy over the last few years and found it odd that he had not called them recently. A similar call came from a friend in Corpus Christi, who would tell several people that she had spoken to Jimmy on the phone on April 29. Jimmy told the friend he would be traveling to the Florida treatment center soon and wanted to see the friend before leaving. The two made plans to meet, but Jimmy never showed up. The friend later visited Jimmy’s house and found no one home, but noticed that Jimmy’s driver’s license was sitting on the kitchen table. The friend was worried—and now so was Sissy Farenthold.

In June 1989, two months after Jimmy’s last known contact, Sissy and her daughter, Emilie, paid a visit to the San Antonio Police Department and filed a missing persons report. The officers were not altogether encouraging. Your son’s an adult, they said. Even if we locate him, he’s entitled to his privacy. The police assured Sissy that they would do what they could. But she returned to the department a year later and found that her son’s name had not been entered into the police computer. The months passed without any news about Jimmy. For Sissy Farenthold, the familiar fatalism was difficult to resist. Her son was burdened with all the family millstones. Jimmy was dyslexic, a free-bleeder, unhinged by tragedy, perilously addicted; a child of 33, part of him still waiting at the screen door for Vincent, the other part seeking to join his twin in death. He was the embodiment of an entire family’s degeneration. To hope for Jimmy was to ignore history.

ALL OF THIS REMAINED A QUIET family matter until the fall of 1991, when George Farenthold, Sr., six years divorced from Sissy, decided to launch a public crusade.

His role in the Farenthold family dynamic had been less noticeable to the public eye but at least as significant as Sissy’s. George was a heavy drinker, according to various family members, and often became verbally explosive after having a few too many. Frequently he directed his wrath at his children, particularly his three boys, who wore long hair and showed no signs of following in their father’s footsteps as military-minded aristocratic capitalists. They were more liberal than their father, and they took drugs, which George flushed down the toilet whenever he could. The boys were failures, and George let them know it.

“Jimmy was always my favorite,” he says today, but at times the father had a curious way of showing his affection. In early 1989, while George was moving his property to a new house in Corpus Christi, five of his valuable paintings were stolen. George accused Jimmy of being the thief. Jimmy was deeply offended by the charge and remained so up until the time of his disappearance.

Yet he continually sought his father’s approval, just as he had his mother’s. When George suffered a stroke in August 1988, Jimmy’s fear that his father would die was dramatically apparent to Sissy. It was hard to fathom Jimmy’s wandering off for good and not once checking in on his ailing father.

In the meantime, guilt gnawed at George Farenthold, now 75 and living alone with his memories, his conscience, and his advancing decrepitude. At times he would lash out at his absent son, saying he wished he could find Jimmy so that he could throw him in prison; at other times he would cry. “I want to see my son before I die,” he would say. The lack of news as to his son’s whereabouts taxed his patience, and the family’s obsession with grieving behind closed doors irked him. At three family meetings, Sissy and the Farenthold children urged George not to take drastic action, but the father was undeterred. He told his story to a reporter from the San Antonio Express-News, who then interviewed several friends of Jimmy’s, each of whom had been fuming over Sissy Farenthold’s unwillingness to air the matter publicly. Jimmy had always been a family embarrassment; perhaps, some suggested, Sissy was glad her son was gone. Or perhaps she was responsible for his being gone. Maybe she had had him institutionalized, they told the reporter, who published the unsubstantiated theory. She is hiding something, they insisted. Why else would a mother be silent about her missing son?

After the article appeared this past January, George Farenthold, Sr., found that his ex-wife and his children were not speaking to him. More family blood had been spilled, and there was nothing but pain to show for it. “I’m just as confused as I was the day I started,” the grieving father would say. No one had a clue where his son was—not the Nueces County Sheriff’s Department, not the two private detectives the family had hired, not a single relative or friend.

Today it has been three years since James Robert Dougherty Farenthold made his customary Mother’s Day telephone calls to his surrogate families; three years since he told friends in Corpus Christi he would return from the Florida treatment center a changed man; three years since he departed the edge, heading in one of two directions—but in either case, away from the family.

“IT WAS A THOMAS HARDY DAY,” Sissy Farenthold would say of the wet, ash-gray afternoon of February 4, 1992, when what was left of the great family gathered in Beeville to bury another one of their own. The forty-year-old man was Jimmy Farenthold’s second cousin, Sissy’s first cousin. The obituary would discreetly note that he had died accidentally. In truth he died of a drug overdose.

Had Jimmy Farenthold been there instead of wherever he is today, he might have been a pallbearer. In Jimmy’s absence, those who remained—though for how long, Lord?—bore the burden of their kin through the mud and the wind and laid him down next to the others who had fallen.

Under the darkening skies, they stood there for a time. Among them was Sissy, whose brown trench coat was wrapped tightly around her body and whose enormous sunglasses obscured the top half of her face. When she bowed her head at the prayer, her expression and all that it might tell the world was completely hidden from view. For that brief moment, she too had disappeared, and surely to a better world. Then the moment passed. The Catholic priest said all there was to say, after which Sissy Farenthold and her family turned to go, hastening before the storm clouds burst again.