This story is from Texas Monthly’s archives. We have left the text as it was originally published to maintain a clear historical record. Read more here about our archive digitization project.

When asked how they went about the business of setting the woods on fire, the three young men who had been discussing their love of hunting fell into an abrupt silence. One of them turned away and stirred the coals in the barbecue pit, preparing the fire for the freshly dressed deer that the three had killed just yesterday, a full week after the close of deer season. Another hunter stared blankly at a lumber truck rumbling south down Texas Highway 62 toward Mauriceville. The third gazed at the muddy ground while a smile slowly formed on his unshaven face.

“Wait here a minute,” he said.

He retreated to a toolshed, accompanied by his hunting dog—a Walker hound bred for chasing deer—and returned with his hand behind his back, grinning fiendishly. The young man held out a fist-size ball of cotton and dipped it into the barbecue pit. Just as the flame began to catch, he blew on the cotton ball, then flung it into the muddy grass nearby. The cotton ball sat there, billowing smoke.

“Like that,” he said, laughing. “Just toss a few of ’em from the window of your truck. You go when it’s dry weather, when a good breeze is going . . .”

The smoke from the cotton ball seemed to complete his sentence. One of the other hunters, scarcely more than a boy, said, “They oughta give us back December and January to hunt with our dogs.”

The last to speak nodded his head. “If it wasn’t for hunting, I’d be about done,” he said. “I got three kids to feed, and I’m on disability on account of my back.” He glanced wistfully at the piney woods behind the trailer home. “Man takes food off your table, you can shoot his ass,” he said in a low voice. “Government does it, you can’t do a damn thing about it.”

The youngest then said in a grave voice, “If they’d let us have the last half of deer season again to hunt with our dogs, there wouldn’t be no trouble.”

Until then, the trouble would continue. Since 1988, arsonists had torched more than 50,000 acres of timberland in southeast Texas. The past year had been rainier than the one before and the number of arson fires had dipped from 233 to 154 in 1994. The new year began with rain, and East Texas firefighters prayed that the bad weather would swallow up the winter and be followed by a warm spring, producing green foliage, which would be slow to burn. But February was not over before the fires began again, right on schedule.

There had always been arson in the vast forests of East Texas, and for the past seven years many of the suspects were dogmen—the hunters who continued to hunt deer with dogs even after the banning of the sport in 1990. If you believed the thirty or so dogmen who were thought to be responsible for the fires, deer hunting was the only way to feed their families. If you believed them, a true sportsman didn’t ambush deer while sitting in a blind; rather, he set out his dogs and waited for that split second afforded him to aim and spray his buckshot at the blur zigzagging through the woods. If you believed them, their enemies—the Texas Parks and Wildlife game wardens—were henchmen of the timber barons, who wanted the dogmen off their property so that it could be leased to rich hunters from the city. If you believed them, the state had taken the caretakers of a great East Texas tradition and made them outlaws. And if you believed them, the dogmen only wanted a little consideration—say, half a season to run their dogs—and then the burnings would stop.

You would have to be more than a little gullible to believe all of this. But you would still have to take the arsonists seriously. The three young men by the barbecue pit were believed to have torched thousands of acres in a region known as the Devil’s Pocket, forty miles due north of Orange and just west of the Louisiana border. The smoldering cotton balls had cost the timber companies hundreds of thousands of dollars in lost saplings, the state tens of thousands more to put out the fires—not to mention endangered the lives of the Texas Forest Service’s firefighters. No one had yet died from a dogman’s fire. But the particularly vicious nature of sapling fires, combined with the violent relationship between many East Texas hunters and state game wardens, guarantees that this will surely change. Even as state officials dread this inevitability, many agree with what one of them said aloud, just as the burning season of 1995 began: “It’s going to take a few funerals before anyone realizes what we’re dealing with out here.”

Last December the flames came way too close for comfort. On the fourth of that month, the recently built house of Hemphill game warden Mike Alexander was burned to the ground just a few hours after Alexander had cited dogmen for hunting violations. Three dogmen were arrested and charged with arson. If the Sabine County jury finds the suspects guilty at this month’s trial, the case will become the first successful prosecution of a dogman committing an act of arson. That sobering statistic, along with the fear that some members of the arson party may escape indictment altogether, has East Texas officials worried that the outcome of the trial will only serve to fan the dogmen’s flames.

Those who have burned the woods of East Texas possess an almost exotic stupidity, along with a sociopathic ability to rationalize wild violence. They bear little resemblance to the true East Texas sportsman, but like bastard children, they cannot be easily written off. For there are reasons why they exist in this part of the world and have existed here for so long, quietly abhorred by the decent folk and law-abiding hunters who nevertheless turn the other way at the sight of a rogue flame. The reasons are older than the East Texas pines, rooted in a tradition that has outlasted any fire, any flood, any wind of change.

Pressed deep into the southeastern hip of Texas are roads that progress has yet to navigate. They lead to stone-silent shantytowns like Call and Old Salem that dead-ended a century ago and to communities like Erin and Fred, where, for some, life goes on without running water or indoor toilets. There are towns like Buna, which is big enough to host a 3A high school but too poor to have its own police force, making it a magnet for the lawless. But Buna is tame compared with the land just east, through which FM 253 travels until the concrete gives way to clay and forms a muddy loop, encompassing a region unnamed on any map but known to all as the Devil’s Pocket. It is a spited territory, blemished with junked autos and caved-in trailer homes—a land of seamless desolation, save for the mornings when outlaw hunters run their dogs, or fling a few smoldering cotton balls into the timber companies’ plantations and set the Devil’s Pocket ablaze.

To think of East Texas is to imagine an enduring 15-million-acre Pine Curtain. Yet even the pines are a relatively new presence, having been raised from saplings only sixty years ago following the rape of the pine uplands and the hardwood bottomlands by timber barons. The forests have been cut down and raised anew; the mountain lions and the bears had been wiped out but are now returning. Change has touched everything in East Texas several times over, but it has always saved the people of the region for last.

Deprived of any hope that progress might bring, East Texans cling fast to tradition. They turn to God, family, and physical force with an intensity unmatched elsewhere in the state. But these three traditions have spawned a fourth—a rite observed throughout Texas, though regarded in East Texas as the culmination of all that is spiritual, social, and primal: hunting.

“The tradition is ingrained and inherited,” a lifelong East Texas hunter told me. “I worked hard as a kid, but nothing like my daddy and grandpa. They worked daylight to dark in the fields and the log woods. Come night, they’d set their traps to make money off the fur. Their only recreation, their only escape, was hunting and fishing. Now, of course they needed the meat and the fur. But what made the love deeper was that life on this land was hard, and they had invested their whole lives here. That they could then take pleasure from the land—that was the ultimate. ”

Yet the land was not theirs. The timber companies own three fourths of the land in several of the counties in East Texas. For many generations the Temple lumber companies (now TempleInland) and Kirby Lumber (now Louisiana-Pacific) tolerated and sometimes invited the locals to hunt on their land—Kirby even went so far as to print a brochure to this effect, titled “acres for the asking.” It was a neighborly gesture, not to mention a politically astute one, as trespassing seemed preferable to a proletarian uprising. The hunters freely roamed the woods, developing an intimate familiarity with the land and, along the way, a sense of ownership. But the timber companies were the true owners and had the deeds to prove it. The land was always theirs to do with as they saw fit—to give to the hunters and then to take away.

For that matter, the hunters didn’t own their prey either. Game animals are the property of the state, and East Texas provides the best illustration of why this is desirable. By the turn of the century, the region’s hunters had all but wiped out the wild turkey, just as the trappers had eliminated the river otter, beaver, black bear, and mountain lion. By the end of the thirties, the hunters had conspired with the clear-cutting timber barons to make East Texas uninhabitable for the white-tailed deer. Recognizing that the region’s insatiable appetite for hunting had reached destructive proportions, the state’s Game, Fish, and Oyster Commission (now known as the Texas Parks and Wildlife Department) in 1938 took the radical step of trapping deer in South and Central Texas and relocating them to the Piney Woods. For the next fifty years the government would continue to move deer eastward in an effort to rebuild a healthy whitetail population. The restoration effort would prove successful, but it was not enough simply to cart 12,149 deer to East Texas and hope for the best. With the deer came laws, and game wardens to enforce them.

Thus has the most treasured form of recreation in East Texas rested precariously on the twin shoulders of the government and the elite landowners. Every shrug has rocked tradition, setting off tremors deeply felt and not so easily absorbed.

Of all the hunting traditions, that which is most time-honored is the East Texas tradition of hunting deer with dogs. It is a practice well suited to the region: a pursuit through the prey’s elements, a communion with brothers and beasts and backwoods. The dogmen are a righteous lot, proud of the Walker and bluetick hounds they raise from pups, proud of their split-second aim, and especially proud of their sportsmanship. One old-timer represented the dogmen’s views well when he told me, “We give a deer a fair chance. He’s running, and he knows we’re after him. And them sumbitches is smart. If you’ve outsmarted him, then you’ve done something. It ain’t like sitting up there like those still hunters in their blinds, waiting for a deer to come up and eat corn out of your hand. We’re the last sportsmen.”

But theirs is also an arrogant sport, one that inherently runs amok, paying no heed to property lines or the concerns of others nearby. All must give way to the chase—and unlike bird dogs, deer dogs pursue their quarry over great distances and for great lengths of time, with no pretense of being under their masters’ control. It is a pastime at odds with a growing society: Where civilization has come roaring through, the dogmen have gone the way of the Apache. The Texas Legislature had outlawed the sport as far back as 1925, but a quirk in the game laws allowed nearly half of the state’s counties to form their own hunting regulations. Still, even those counties that opted for local control exhibited a growing distaste for hunting deer with dogs. By the seventies, only ten counties—the deep East Texas counties of Hardin, Harrison, Jasper, Newton, Orange, Panola, Polk, Sabine, San Jacinto, and Tyler—remained sanctuaries of the dogmen.

But in the seventies, when forty years’ worth of deer restocking in East Texas finally showed vast improvement in the whitetail population, buck hunting became a lucrative enterprise. The timber companies seized the opportunity and, exercising both their legal rights and their capitalist impulses, began leasing blocks of their land to private hunting clubs. Fences were put up. Signs were posted. Game wardens patrolled the acreage to see that the signs were obeyed. In came the still hunters from Beaumont, Houston, and Galveston. Up went their deer blinds. The dreaded twin shoulders—government and the power elite—had shrugged. The dogmen were fenced out. Their tradition was imperiled. But to many of them, a traditional solution was at hand. For in this part of the world, fences, like game laws, were meant to be broken.

When I was a boy, my family in Polk County sometimes hunted deer illegally,” said Larry Williford in his gentle twang as he sat beside the Neches River on the acreage where he nowadays does his hunting and fishing. “Not to break the law. Just to hunt for the love of hunting, in spite of the laws. We’d hunt off-season, we’d occasionally shoot a doe, and we’d occasionally shoot more than our limit. And if the game warden came by, I knew as a boy to keep my mouth shut.

“Now, my uncle Zach was looked up to throughout our family and throughout Polk County as a whole. And by, say, 1952, we began to notice that a game warden would come and visit his house. And over time, the game warden would stay for dinner. Uncle Zach began to visit family members. He told us, ‘Folks, as you know, I’ve been getting to know the local game warden. He has convinced me that we have pretty much killed out all the deer in Polk County. Soon there won’t be any left, and we won’t be able to hunt anymore. The game warden says that we have got to learn how to conserve. He says the game laws are there to protect the deer so that we’ll always be able to enjoy hunting. He says that, and I believe him. So from this day forward, I will never hunt illegally again. And if I catch anyone illegally hunting—including anyone in my own family—then I will turn him in to the game warden.’

“Half of the family went along with Uncle Zach,” said Williford, who followed the example of his uncle and today is the commander of the fifty game wardens stationed in East Texas. “and the other half remained outlaw hunters. And even now, a couple of generations later, some members of the family still choose to hunt illegally.”

Game laws have existed in Texas since 1861, when a two-year closed season on bobwhite quail hunting was enforced in Galveston. The regulations proliferated; by the end of World War II, there were hundreds of them, ranging from the ban on headlight hunting in 1903 to the establishment of wildlife management areas for bighorn sheep in 1945. Throughout the state, some sportsmen have carefully obeyed the laws while others have not. But according to Commander Williford, it is a statistically verifiable fact that more hunting laws have been broken in East Texas than anywhere else in the state.

In a region where hunting went beyond mere sport and into the realm of catharsis, game laws were for decades viewed with disdain—not only by hunters, but also by the local lawmen, district attorneys, and judges. Over time, most East Texans came to accept the reality of hunting regulations and elected enlightened officials who showed a willingness to punish game-law offenders. Still, the tradition of outlaw hunting remained, passed down from father to son, as in Commander Williford’s family. Even in the face of compelling evidence that deer populations needed to be protected, hunters continued to hunt how, when, and where they pleased. For those so willing to ignore the laws of biology and the laws of the state, by the seventies it had also become an easy matter to ignore the laws of the landowners.

“When the timber companies started leasing the land, trying to get a little money, these old dog hunters really bucked it,” said Billy Platt, a lifelong East Texan who served as a game warden from 1962 to 1985. “You’d build a two-mile fence and the next day someone had cut it all down. We had to start pushing ’em real heavy.” The fines levied by game wardens had some noticeable effect. More and more dogmen saw that their sport was doomed, sold their dogs, and joined the still hunters in their blinds. Several others formed their own hunting clubs, pooled their money, and grudgingly leased land from the timber companies. But there remained a stubborn core who would not give ground. Accompanying their usual recreation was, according to Commander Williford, a new pastime—aggravating the still hunters. A few dogmen delighted in turning their dogs loose on leased land, where a still hunter who had been waiting all morning in his blind would at last aim at his quarry, only to see it chased out of range by a pack of Walker hounds.

The tactics were mostly desperate. When the 1983 Wildlife Conservation Act gave full control over game laws to the Parks and Wildlife Department, the dogmen knew the state would eventually move to quash them for good. Sure enough, Parks and Wildlife ruled in 1986 that the dogmen could only hunt in the last half of the deer season. To add insult to injury, the department initiated the Type II program in 1987, leasing hundreds of thousands of timberland acres that had been open to free hunting and charging all comers a $35 permit fee—money that, the dogmen noted bitterly, would be lining the pockets of the timber companies.

But the final blow came in the spring of 1990, when an updated Parks and Wildlife staff report titled “Hunting Deer With Dogs” began making the rounds. The study was spearheaded by a respected state deer biologist named Gary Spencer, who surveyed the ten counties that still permitted the dogmen’s sport. Spencer found that only 10.9 percent of the region’s hunters currently used dogs to hunt deer and that 73.3 percent of the area’s hunters and 75.2 percent of its landowners opposed the practice. But the most damning aspect of the report came in a single sentence: “The results of this investigation have documented that a danger of depletion of the deer resource exists on lands where deer hunting with dogs is permitted and that this danger of depletion is directly related to some factor or combination of factors associated with the practice of hunting deer with dogs.”

To the dogmen, and even to a few game wardens, this notion seemed preposterous. How could only 10.9 percent of the hunters be blamed for “depletion of the deer resource”? How could four hunters with eight dogs chasing a single whitetail kill more deer than four still hunters stationed in four deer blinds? It didn’t make sense, and today people on both sides of the issue still shake their heads when the Spencer study is brought up. Everyone knew that the dispute boiled down to property rights, not deer depletion. But what the dogmen did not know was that, according to the Wildlife Conservation Act of 1983, the Parks and Wildlife Commission could, for all practical purposes, change hunting regulations only “if the Commission finds that there is a danger of depletion or waste . . .” Sociological reasons wouldn’t be enough to ban the dogmen. A biological basis was necessary, and Spencer’s study delivered it.

In mid-April 1990, public hearings on hunting deer with dogs were held by Parks and Wildlife in each of the ten counties. The dogmen turned out in force, and though they knew the ban on their sport was imminent, they intended to have their say. Chiding the study, a man in Newton County asked, “How do you figure a deer can do better standing than running? I want to see that survey. ” In Sabine County, a dogman wondered aloud, “Are you trying to protect the deer or the timber companies?” A man in Jasper County said, “If the government had polled the people on equal rights for colored people, ninety percent of them would’ve been against it. But that don’t make it right!”

Charges of greed, corruption, and communism were general throughout the assemblies. Almost every speaker cited tradition: “My granddaddy hunted with dogs, my daddy did, and by God, my son will hunt with them too.” But a few spoke in the desperate tones of the soon-to-be-defeated. What will we do for recreation? What will we do with our dogs? And where will all of this end? In Newton County, one speaker quoted the Spencer study’s finding that the dogmen were dwindling in number. He then asked a heartbreakingly plaintive question: “Why don’t they just let us decrease till we’re gone?”

Today the recordings of the hearings sound almost like the sad oral histories of a vanquished culture. But in light of what was to come, a few of the remarks had ominous overtones. Two speakers from the raucous assembly in Hardin County come especially to mind. Said one of them into the microphone: “If you’re gonna kick a dog long enough, he’s gonna chew on your leg . . . Everyone here ought to be up in arms.” Said the other speaker: “A whole lot of outlaw hunting and a whole lot of land violating and a whole lot of other stuff is gonna happen when you delete the dogs.”

Exactly what “other stuff” the latter speaker never made clear. But away from the microphone, a few of the dogmen approached game wardens and told them what other stuff they, at least, had in mind.

Said the dogmen: “If you don’t let us hunt with dogs, we’re gonna burn the woods down.”

As a people, East Texans have always been quick to use physical force,” Commander Williford told me. “We have suffered the scars of poverty as much as anyone, and there is something we carry in us that says, ‘I am not going back to where I’ve been and to where my daddy’s been. I will not be pushed.’ But because our poverty and our long hours of labor kept many of us from an adequate education, we haven’t always understood why we were being pushed. We just feel the force of it. And not being able to win a war of words, we just push back as hard as we can.”

When East Texans have felt the force of hunting laws, they have, according to Williford, responded by committing more violence against game wardens than have hunters from any other region in the state. Two game wardens have been murdered by East Texas hunters; numerous others have been assaulted at gunpoint; more still have received death threats. But threats and guns are useless to those who wish to lash out at the powerful yet faceless landowners. Instead, they resort to another method of violence—a lesser and seldom discussed pastime, but one that is as much a fact of life in East Texas as poverty, monotony, resentment, and ignorance. Says Ron Dosser, a twenty-year veteran of the Texas Forest Service in Kirbyville well acquainted with this matter: “There are people here, historically, who for whatever reason have wanted to burn the woods. It’s just a tradition for some people here.”

The whispered threat of arson has always hung over the region like a grim superstition. A timber company official who fired a truant lumberman, a hunting club that expelled a member, a property owner who shot a hunter’s trespassing dog, an eavesdropper who thought about reporting a few outlaws to the authorities—all of them might get the message, in word or in deed: Your land will burn for this. While some have used arson to settle scores, cattlemen have torched land to yield grazing areas just as deer hunters have burned off selected roadside acreage to attract whitetails to the foliage that would replace the saplings. Yet even these seemingly “constructive” burnings were implicitly defiant and hostile. It was the arsonist’s way of cutting the rich boys down to size, a way of meting out his own primitive justice.

The craft of arson would be passed down as well. The arsonist would wait out the rainy winter in anticipation of late February, when the air would be dry and breezy and the new green foliage not yet evident. He would then assemble the tools of the trade: balls of cotton, a weighted cotton rope spiked with matchsticks, or simply a matchbook with a lit cigarette protruding from one end. (The latest innovation has been mosquito coils, which will smolder for as long as two hours before igniting, providing the arsonist ample time for escape. Says one local law enforcement official: “Go to the Wal-Mart in Vidor in February and ask for the mosquito coil. You’ll find they’re sold out. And considering it’s cold weather, you know they’re not buying them for the mosquitoes.”) The act itself could be accomplished at night for maximum security, but in truth, a stealthy arsonist could fulfill his mission in broad daylight with a few casual flings of the wrist out of his truck window.

Such acts required no special skill of any kind. Still, to set the woods on fire was to break from society as a whole and embrace the life of a brute. When an individual responded to change by committing arson, he passed into a realm of primitive dimness from which there would be no return.

So it was that in 1990, following the banning of their sport, the dogmen stared change in the face and responded in one of three ways. Most of them grimly acquiesced, gave up their dogs, and moved forward with their lives. Many clung stubbornly to tradition and became outlaw hunters by continuing to hunt deer with dogs. But from the ranks of the latter emerged a third group, a criminal fringe for whom it was not enough simply to disobey laws and trespass the land of the timber companies. For them, the only response to change was to lash out wildly and burn the timberlands to the ground.

A month after the public hearings, a crudely written note was found tacked to the front door of a timber company’s office. It read, “If the state outlaws deer dogs we will burn your land in dry weather, plant cudzu vines in wet weather 5, 10, 20 yrs. Whatever it takes to keep running our deer dogs. Think about your forest 10, 20 yrs. ahead with cudzu vines growing in hot, humid East Texas. It will be thicker here than in Ga., Miss., Ala. or any other state.”

Not long after that, a gate leading into a torched plantation bore the scrawled message, “Where the dogs can’t go, the pines won’t grow.” Where other acres burned, firefighters reported finding charred bags of dog food. In the past, area officials had noticed a correlation between the incidence of burnings and changes in hunting regulations—the leasing of the timberlands, the initiation of Type II—but by 1990 there was no longer any need to connect the dots. The dogmen had done it for them.

In so doing, they became what they remain today: outlaws among outlaws, reviled even in their own ranks. “I told them boys that this burning’s a bunch of crap,” one middle-aged dogman gravely said to me. “I mean, it’s gonna come back to haunt us. Hell, we work and live on that land they’re burning!” Yet the arsonists would view their destruction through a blind spot as big as the woods. One suspected ringleader spent an afternoon driving me up and down the frequently torched plantations abutting Gist Road, between Buna and Mauriceville, and while gesturing toward the charred acreage, he crowed out one rationale after the next: “Now, we burnt the shit out of this area over here, but we didn’t kill no pine sap—just killed the other brush. ’Course, when those lumber people burn it, they call it controlled burning. Shit, what’s the difference? . . . See this? This has been burnt three years in a row. See what pretty pines? . . . Now, I’m afraid to set that shit over there on fire because it might jump the road and burn one of those trailers up there. We ain’t ever burnt up a place around here.”

It would be possible to dismiss the arsonists as delusionary bullies if, as they claim, their handiwork was essentially harmless. Incredibly, it was not until 1989 that the state legislature was convinced otherwise, for before that year a case of woods arson was considered a crime only if a habitation was damaged. (As a result of the new law, maliciously burning the woods is a felony punishable by up to life imprisonment and a $10,000 fine.) It is a fact, regardless, that arson fires consume thousands of acres of pine saplings, and the richly fueled wood causes the flame to move wildly across the plantations, achieving particularly intense heat and leaping as high as fifty feet in the air. Though many of them are contained within an acre or two, others resemble the act of arson committed by an outlaw hunter in Nacogdoches County in 1989, which raged uncontrollably for days and swallowed up more than a million dollars’ worth of property—the worst money-loss crime in the county in more than a decade.

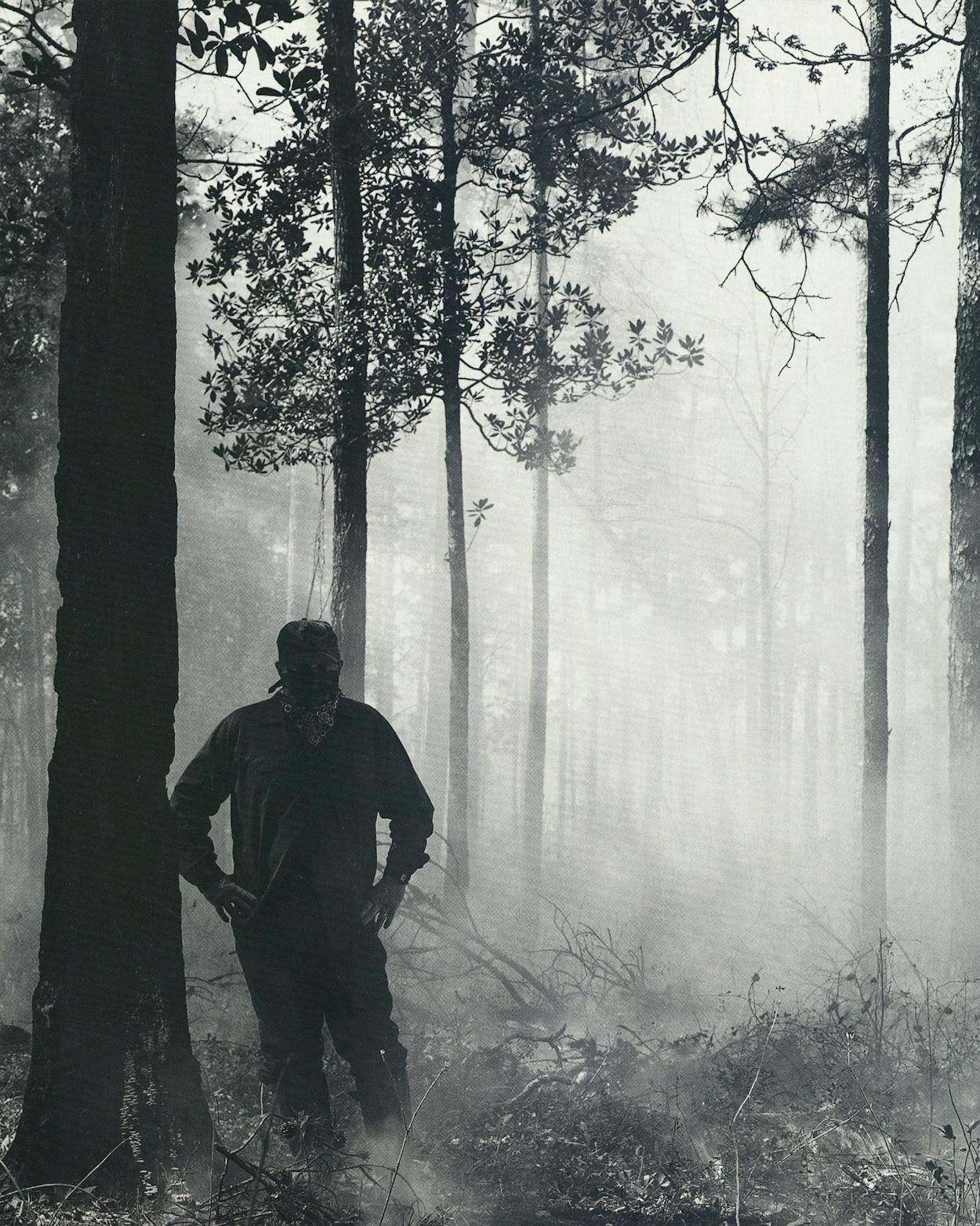

These are fires designed to spread. And they would do so through whole neighborhoods were it not for the small group of Texas Forest Service firefighters who continue to save East Texas from its sick few. It has fallen to the firefighters to contend with road-jumping flames and the malevolent sorcery of the dry north winds, to attack one fire while other fires nearby spread unchecked until backup crews can arrive from around the state, as was necessary last fall when arsonists set 43 fires in one day along Gist Road. The firefighters’ work is dangerous anywhere, but particularly so in the forests, where their fire vehicles often get stuck in the boggy timber soil. Time and again the firefighters have had to abandon their stuck dozers and run for their lives through the swirling flames back to their fire trucks—where they find that the arsonists have sprinkled nails around the tires.

The firefighters, like the local lawmen and the game wardens, know who many of the arsonists are. But knowing and proving are two different things. To catch an arsonist in the act of burning the woods is a needle-in-the-haystack proposition for the handful of lawmen who patrol the vast pine thicket. “Over the years, I’ve been involved in virtually every kind of criminal case that’s on the books,” said Charlie Neel, a former Texas Ranger who is now Temple-Inland’s director of corporate security. “And without a doubt, arson is absolutely the hardest case to put together.”

That woods arsonists are not likely to be brought to justice has put Neel and other East Texas timber officials in a bind. Though the land belongs to the lumber companies, it is the dogmen, not the industry executives, who are a guerrilla presence there and who know every stand in the forest. Effectively held hostage by the arsonists, the lumber companies have elected, as one forestry official put it, “not to agitate them.” Timber officials have publicly dismissed woods arson as a nuisance problem in the lame hope that the burners will become discouraged and give up. Only privately do they articulate their fear of what might happen if arsonists learned that their burnings—when one considers current timber prices at around $2,500 an acre—have cost the companies nearly $10 million a year.

Collaring the arsonists requires eyewitnesses, and several have come forth—only to recant their statements later, citing the age-old fear that their houses will be torched. “That’s the story they have always told me since I got here,” said Hemphill game warden Mike Alexander, a thick-framed young man with a round, impassive face. “The witnesses would tell me, ‘If they find out I called you, they’ll burn my house down.’ That’s just the standard line.”

Until last December, Alexander would always reply to the witnesses that such a thing had never happened. But on the morning of December 4, the game warden received a call—“a typical anonymous call,” he said, “because she was scared”—that hunters were spotted chasing deer with dogs just outside of Hemphill. Alexander tracked down a group of eleven hunters, ranging in age from 17 to 43. One of them was hiding in the woods with a freshly killed antlerless buck. Alexander arrested him and took both the hunter and the deer down to the Sabine County Sheriff’s Department. While he was booking the suspect, one of the other hunters slashed the ropes tying the deer to Alexander’s Blazer outside. He too was arrested.

The hunters were “mouthy,” Alexander recalled, which did not altogether surprise him: a number of them were outlaw hunters with whom he had had run-ins in the past. Dogmen like these, he said, “are basically not going to abide by any of the laws. Even when it was legal to hunt with dogs, they would hunt illegally. They would hunt out of season, hunt at night, shoot from the road, shoot does, shoot more than their limit.” From some of them, Alexander would hear the refrain that they hunted out of necessity, to feed their families. The game warden was not moved. “I can’t remember ever checking any illegal hunter who didn’t have a case of beer iced down, a full tank of gas in his truck, and plenty of bullets in his gun,” he told me.

Alexander completed his paperwork that afternoon with the belief that the incident was routine and would not require his further attention. He was wrong. That evening, the recently built $83,000 house he would soon be moving into with his family was burned to the ground. Two days later, three dogmen—two from the hunting party Alexander had cited for game violations—were arrested and charged with conspiracy to commit arson.

The burning of the game warden’s house, ghastly and anomalous though it appeared, was a signal event for all of East Texas. For residents, an oft-voiced fear had now been realized: True to his threat, a dogman would do to your house what he has done to the timberlands. More than a few dogmen held to their belief that by banning deer hunting with dogs, the state had invited such incidents—“And there’s gonna be more,” one dogman sternly told me. One suspected arsonist I spoke with seemed gleeful over the house burning. “Burnt that sumbitch right down,” he cackled. “One ol’ boy I know is telling people I’m trying to find out where the Orange County game warden lives!”

Yet through their righteous and vindictive talk, a sense of unease pervaded the ranks of the outlaw hunters. Did any of them think that by burning down a game warden’s house, the dogmen would win back their sport? In raising the ire of the state, the arsonists may have at last ignited a fatal backfire. Commander Larry Williford told me one afternoon, while we sat and ate apples at a picnic table beside the Neches River, that he will not rest until every man responsible for the burning of Mike Alexander’s house is brought to justice. “Over the years,” he said in his soft, contemplative voice, “I had a game warden or two come into my office and say, ‘Well, I walked into this fellow’s camp and he said a man could get his ass kicked around here. Should we press charges?’ and I’d say, ‘Well, it’s probably just beer talk. Let’s leave it lay.’ We have gone the extra mile to be lenient. And now it seems about a mile too far.”

He stared at the river for a moment before saying, “We are going to be professionals. But we are going to do our jobs and not be stomped into the mud by a handful of thugs. We will file on them and file on them and file on them. And if anyone ever again threatens one of my people, he will be handcuffed and carried off to jail. I don’t control but about fifty game wardens. But I can take those fifty, at any given moment, without having to ask anyone’s permission, and send them wherever I want.”

Williford then frowned. “But I do have fear about this case,” he confessed. “The fear I have is whether the people of Sabine County are ready to say, ‘This is what happens if you do this.’ ”

The game warden commander can move his men, but not the rooted ways of his region. Only four weeks after Alexander’s house burned down, the house of Jasper County justice of the peace Clifford Wood was also incinerated. Wood is well known in the area for his stern punishment of game-law offenders, frequently incurring their wrath. “If they ever catch who did it,” former game warden Billy Platt told me, “my belief is it’ll be an outlaw deer hunter.” Catching the arsonist may require an eyewitness, and perhaps one will eventually come forth, breaking through a psychic barrier that has imprisoned East Texas as much as economic misfortune.

“It just takes people a while to adjust to change here,” Newton County sheriff Wayne Powell told me one afternoon. The good-humored 57-year-old sheriff of one of the state’s poorest and most arson-afflicted counties sat behind his desk, lit a cigarette, and then proceeded to tell me a story. “We’ve got a place down here that’s now owned and operated by a man named Blanchard,” he said. “Before he owned it, for many years people would go there on that land and picnic at the springs there and take some of the sand out of the pits so that they could make a sandbox for their kid. Well, this man Blanchard moves in from the Vidor area, and he buys this property. It’s legally his. No doubt about that. But people would keep going down there and Mr. Blanchard started filing trespassing charges. They tore up his fence and cut it up and hauled it off as retaliation. But now he’s down there running a nice business, and people have accepted the fact that it’s his.”

Sheriff Powell took a long drag on his cigarette. “People my age have had the run of the woods all their lives,” he said. “Their grandfathers and their fathers and now them. Then all the timber companies say they’re going to lease out their land and give other parts to Type II. It’s just another one of those changes.”

Shrugging, he added, “But I’ll say this. It might start today again, the burning of the woods. But there’s been a lot less of it. I don’t hear much about it anymore. And I hope I’ll hear it even less.”

That very afternoon, the first relatively dry day of the year in the area, an arsonist set fire to an acre in Newton County. The following day saw more fire in the county. Burning season had begun.

People adjust, but not Without hardship. Among the many voices recorded in the 1990 public hearings over the dog-hunting issue, the one that stayed in my ears belonged to an elderly man in Newton County named H. T. Jones. On the tape, his voice often quavered, but the earnestness of his anger was unmistakable as he excoriated the timber companies (“King Arthur,” he spat out in reference to Temple-Inland director Arthur Temple, Jr.), the state wildlife officials, and the condition of a nation that would not even allow a man to hunt with dogs on his own property.

I showed up one morning on the porch of H. T. Jones, whose house was nestled in the woods on the outskirts of Bleakwood. Half-expecting to be greeted by a mean old cuss with a shotgun in his hand, I instead found a slightly enfeebled gentleman wearing a pale blue jumpsuit that matched his eyes. Jones checked my identification, then apologized for doing so and led me inside.

The 69-year-old former dogman and retired pipe fitter had never been issued a citation by a game warden in more than half a century of hunting the woods of East Texas. He was a true sportsman, of which there had always been many in these parts, and he despised the arsonists. For an hour we sat and talked about hunting, the state, and the state of hunting. Jones expounded on his theory of state control and how it related to deer hunting. “The law enforcement officers want someone less mobile than a dog hunter,” he said. “They want him sitting in a stand. They want to know his whereabouts. Everything in life is that way nowadays. I firmly believe that it all comes down to control. And in hunting, just as with everything else, to my notion the little man done lost out.”

I asked him about his dogs. Jones said that he gave them away. “It was a very emotional time for me,” he said quietly. Forcing a smile, he then said, “Of course, times change. Now my wife and I do other things. We go to Colorado and New Mexico. I do love the mountains and the snow. But to me, these woods are still some of the most beautiful country in the world. And nothing I’ve done in the western states compares to the experience of walking through these woods and listening to the beautiful voices of my old hounds trailing a deer. ”

Now his voice was stricken with nostalgia. “I remember that if I had a slack period at work, I’d call the pipe fitters union and tell ’em not to bother me. And my brother and I would go camp out with our dogs. Not even hunt. Just be out there with them, enjoying the outdoors.”

H. T. Jones tried to clear his throat but could not. “It’s different now,” the dogman laughed as tears welled up. “It’s hard to get up.”

- More About:

- Hunting & Fishing

- TM Classics

- Longreads

- East Texas