This story is from Texas Monthly’s archives. We have left the text as it was originally published to maintain a clear historical record. Read more here about our archive digitization project.

It was the first Monday in March, and even at midmorning the Russian sky was wracked with gray clouds. Two white-haired men stood nose-to-nose on a snowy rural plain, one old pol to another. Ambassador Robert S. Strauss put his arm around Moscow mayor Gavriil Popov. They had come to this field, once the country home of Soviet president Leonid Brezhnev, because Popov envisioned it as the perfect location for Moscow’s only English-language school. The whole idea drove Strauss to despair. All the Russians could think about was public projects built with government money—preferably, as in this case, Western money. “When,” Strauss wondered to himself, “will the Russians ever learn to use land to create wealth?” He had been trying for months to get Popov to make use of the public land the city controlled. “What about my idea of corner grocery stores?” prodded Strauss. “Right now all the sausages in Moscow are orphans. Open up private stores, and I promise you the sausages won’t be orphaned anymore.”

This is American foreign policy in Russia today: schools and sausages instead of the cold war and perestroika. It’s a policy driven not by big ideas but by thousands of small and agonizing details. Strauss is not a conventional diplomat, but he does know how to press the flesh with politicians the world over. Popov laughed and tried to show that he understood the capitalist gospel according to Bob Strauss. “The boys who ran the Communist party weren’t good at much,” said Popov, pointing to a grove of leafless birch trees and the land that stretched before them like a scene from a Russian fairy tale, “but they damn sure knew how to choose good real estate.”

The job Strauss was doing in that suburban Moscow field was not the one he signed on for last June. Then the idea was that Strauss, the ultimate political pro, was a natural partner for the embattled Mikhail Gorbachev. Never mind that Strauss wasn’t a Kremlinologist and couldn’t speak Russian—he and Gorbachev shared the language of politics and intrigue. But when Strauss arrived in Moscow last August, in the middle of the three-day coup, events were so muddled that Strauss didn’t even know to whom he should present his diplomatic credentials.

On his first day of work at the American embassy, tanks surrounded the Russian Parliament. Strauss sat at his desk, not knowing where to begin. Then he had an idea. “See if you can get Anatoly Dobrynin on the telephone,” he told his secretary. Dobrynin was the dean of the Soviet Union’s ambassadorial corps. All through the cold war it was Dobrynin who had pressured the Soviet Union to keep talking to the West. At that particular moment, Strauss knew he had to make every phone call count, and his instincts told him Dobrynin was the man to trust. In a few minutes, Dobrynin was on the line.

“I’ve arrived, Anatoly,” Strauss told him. “What’s your assessment of the situation?” Dobrynin’s voice was friendly and reassuring. “You are wise to be cautious and quiet for a while,” he told Strauss. “This coup is a long way from a success. The odds are it won’t succeed. The best thing to do now is to do nothing.”

If Strauss had been a career diplomat, he would have waited for specialized information to come through the maze of proper channels. But Strauss is fundamentally a politician, and he followed his instincts to the man who could best tell him how to survive.

The same instincts guided him the Saturday after the coup, when he went to the funeral of three young Russian men who died defending the Parliament against their own army. “It was the biggest crowd I’ve ever seen by double,” Strauss said. “There must have been four hundred thousand people there.” The Moscow police attempted to herd Strauss toward the diplomatic corps seated on bleachers, far from where Gorbachev was scheduled to speak. “Fellas,” Strauss told the police, “I’m headed for that flatbed truck over there where Gorbachev is. To deliver a message, you need a microphone. I can’t speak for the president of the United States from the goddam bleachers.”

He and his longtime assistant, Vera Murray, started making their way through the crowd. Emotions were high. Many people were crying. When he was within fifty yards of the podium, he was stopped again by more policemen, who told him that he couldn’t pass beyond the ropes. “Look here,” he said, “these ropes are put up by people just like you and me. This is just like a Democratic convention: Everybody here is in charge and nobody’s in charge.”

While the policemen were wondering what was this thing called a Democratic convention, Strauss ducked under the ropes and saw Gorbachev standing behind the truck. The president looked beat. “Who’s going to speak and how long is the program?” Strauss asked Gorbachev. Dazed and exhausted, Gorbachev replied that he would speak for three minutes, then Mayor Popov would speak for three minutes, followed by three-minute talks by a Russian Orthodox priest and then a rabbi. “I would like to speak, Mr. President,” said Strauss. “I think it would be very good for the world to know that my country stands with you.” Gorbachev focused his gaze on Strauss and understood that Strauss was offering him political survival. “You will speak right after I speak,” Gorbachev told him.

Soon it all felt natural to Strauss. He helped the rabbi up the steps to the bed of the truck and hoisted the priest up, and then Gorbachev was reaching for him. Strauss turned and faced the largest crowd of his life. “Remember, this is just like a Democratic convention,” he told himself, and then he looked out and saw wave after wave of grief-stricken Russians. “Your boys did not die in vain,” he told them. “They died for liberty.”

The next evening, he had his nightly cocktail with his wife, Helen, at Spaso House, the official residence of the American ambassador in Moscow. They tuned in Cable News Network and watched the coverage of his funeral speech. “Honey,” he told Helen, “I’m not worried anymore about this job. We can do it.”

At 73, Bob Strauss is the last ambassador to the Soviet Union and the first ambassador to independent Russia. The average American cannot comprehend how completely last year’s revolution transformed every detail of the average Russian’s life. Russians no longer shop in state stores but at flea markets, where ordinary people sell whatever they can find—a bar of soap, a single shoe, a set of cookware—to people who can’t afford to buy. They no longer believe in their own history, nor do they believe the present chaos can last, and the future is only imaginary. “Only the fortunetellers know the future,” one Russian woman told me, “and they are fools. Anyone who believes anything is a fool.”

Their agony is not limited to long food lines, higher subway fares, and the sudden explosion in crime. They have lost their identity. I was in Moscow for nine days in March and never heard a single person refer to the Commonwealth of Independent States. The name Russians have given themselves is the Former Soviet Union—formerly great, formerly real, formerly their own.

Into this moment of history stepped Texan Bob Strauss. As ambassador, his job is to carry out the policies of President George Bush. But when it comes to Russia, Bush has been as politically disoriented as Russian president Boris Yeltsin and considerably more timid. For all of Bush’s talk about the new world order, his vision for Russia has been dim and complicated by his reelection campaign, which is bogged down by domestic economic problems. That leaves Strauss mired in confusion both in Moscow and in Washington. Every day that he passes in Moscow without another coup is a 24-hour measure of success.

To watch him work is to understand that all global problems come down to the work of individual hands. Can Bob Strauss save Russia? He can’t singlehandedly bring the warring republics together, nor can he turn Russia into a capitalistic nation overnight. What he can do is buy both Russia and the United States time with the currency of his own political instincts.

The night before meeting with Gavriil Popov about the new English-language school, Bob and Helen Strauss entertained Russian president Boris Yeltsin and his wife, Naina, over dinner at Spaso House. During a first course of bean soup, they chatted about their grandchildren. Then over veal and pasta, Strauss invited Yeltsin to the United States for his first state visit with President Bush. “How does June look for you, Mr. President?” Strauss asked. Yeltsin pulled his calendar from his coat pocket and said he was free on June 16 and 17. “Fine,” said Strauss, and the deal was closed. They moved on to general discussions about dismantling 27,000 nuclear weapons, especially those outside of Yeltsin’s control, but soon agreed that each of them was doing all he could and rushed nervously to dessert. Yeltsin offered a toast to former president Gorbachev’s upcoming sixty-first birthday, and Strauss happily raised his glass. It was exactly the sort of evening ambassadors are supposed to have.

“Now,” said Strauss the following morning, “here I am, knee-deep in the damn school business.” This is the way Strauss approaches his job. If he can relocate a school, dismantle a few thousand bombs, keep Yeltsin and Bush talking to one another, teach Russians the ABCs of capitalism, and help American businessmen nail down a few deals, then maybe he will have bought enough time for a vision of American policy to emerge. Still, he’s 73, and sometimes the process of juggling so many small and large problems wears him down. “Let me tell you something,” sighed Strauss on the way to meet Popov. “These days of talking about nuclear explosions one hour and the intrigue of local school politics the next are more than I can handle.”

Nonetheless, he displayed no sign of weariness or frustration during his meeting with the mayor. As the two men stood in the field, Strauss trying to close a deal on sausage stores and Popov trying in his own clumsy way to sell a piece of real estate, they could have been two men dealing anywhere in the world. But these negotiations also revealed how Russia and the United States currently see one another. Popov sees the U.S. as his anchor tenant, his hedge against failure. Strauss sees Russia as orphaned and dangerous. He wants Russia to gather its own strength, one corner grocery store at a time, with a minimum of support from the U.S. Each man knew the other’s position, and it was left to Popov to find common ground. “Okay, okay,” he said. “I’ll make you one last deal on the school. Put it here and we will play baseball. ”

I’ve made peace with the fact that I’m never going to be president of the United States,” said Bob Strauss. He was seated in the formal dining room of Spaso House, absentmindedly twirling pasta around his fork. Even though Strauss has never held an elective office, the dream of being president still haunts him. In 1988 he was mentioned as a possible draft candidate for the Democratic nomination. Strauss was 69 then, and after a lifetime of operating backstage in Washington as a lawyer and a troubleshooter, he figured he would make a better president than any of the likely candidates. The problem was getting elected. “I couldn’t have even carried my home state,” said Strauss. “Bush was just too strong in Texas.”

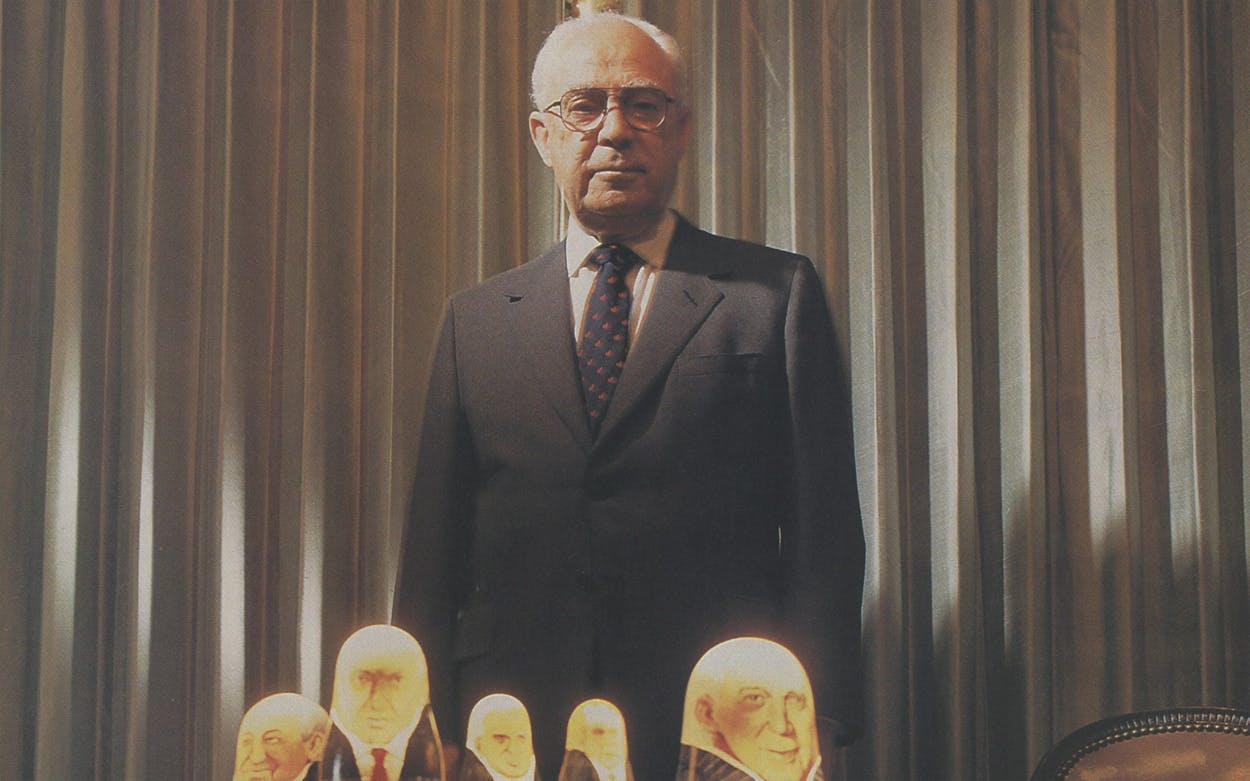

Strauss’s public image is that of the political inside trader. His personal demeanor, however, is not that of a backslapping, loud-talking politician. Instead, he is remarkably low-key, very lawyerlike. I had expected him to sound like his press clippings—an endless stream of funny one-liners—but he is in fact measured, slow to speak, even introspective. Over dinner, he constantly moved the conversation away from himself, soliciting opinions from around the table before offering his own.

His likability is why every president since Lyndon Johnson has trusted Strauss and used him in some strategic way. For Johnson, Strauss was a moneybags. He funneled enormous amounts of money to Johnson’s campaign but was never part of the president’s inner circle. The way Strauss puts it, if President Johnson called a meeting with 10 of his closest advisers, Strauss was not included. But if Johnson expanded the number to 25, Strauss made the cut. Johnson did ask for his advice on Vietnam. “I loved Lyndon, so I told him what he wanted to hear. I told him he was on the right track,” recalled Strauss. “But the moment I walked out of his office, I felt dirty. I vowed never again to lie to a president.”

He had many opportunities to keep that vow. As chairman of the Democratic National Committee, he presided over Jimmy Carter’s election in 1976. Later he made it his regular practice to tell Carter what the president most did not want to hear, including advising against the military rescue of the hostages held in Iran. In 1986, Nancy Reagan asked Strauss to meet privately with her husband about the breaking Iran contra scandal. “I told him this was no twenty-four-hour story and that he ought to fire Donald Regan,” said Strauss. He thought Reagan had ignored his advice, but soon the controversial chief of staff was gone.

The key to understanding Bob Strauss is that no matter how much of an insider he appears to be, he remains in his heart an outsider who grew up in the only Jewish family in the West Texas town of Stamford. “I think being Jewish may have had something to do with why I finally agreed to take this job,” said Strauss. “The Jews have been so mistreated over here.”

His father, Charles Strauss, immigrated from Germany as a teenager and took a job in New York City as a traveling piano salesman. He loved music and wanted to be a concert pianist. On a sales trip through Texas, he met Edith Schwarz, who was reared in Lockhart. They married and opened a small dry goods store in Stamford. They had two sons, Bob and Ted, now an investment banker married to former Dallas mayor Annette Strauss. “I never had anything, but we were not poor,” said Strauss. “My parents bought a new car every five years, and I grew up in a house that cost approximately $3,000. My, how my parents struggled to make those $27-a-month house payments.”

From his father, he inherited a knack for talking to people. As Strauss remembers it, his father preferred to talk to his customers rather than sell them anything. It was his mother who ran the business, and from her, Strauss got his political ambition. She pushed him to go to law school and often teased him about becoming the first real Jewish governor of Texas. “I used to go to my uncle’s house in Fort Worth, and he’d greet me at the door, ‘Here comes Bobby, the first Jewish governor of Texas,’ ” said Strauss, cringing even now. “I would slink away and die of embarrassment.”

His political pattern was set for life in high school—in of all places, the local Baptist church. “The prettiest girls in town were at the Baptist church, so naturally I gravitated to their socials,” Strauss said. One Sunday evening, at a meeting of the Baptist Young People’s Union, Strauss was elected its president. But soon the minister stepped in. “Bobby can’t be your president,” said the minister. “He’s not a member of our church. Bobby is Jewish.” That moment followed Strauss to Washington. There, he’s known as Mister Democrat, the Wise Man, Disraeli With a Rolodex, but he has never managed to completely shake the role of the outsider.

Seated in his easy chair in his upstairs den at Spaso House, sipping Georgian vodka, Strauss considered the irony of his life. “I can sit here today and be the ambassador to Russia, but I could never be a member of the Dallas Country Club,” he said. Even now, it is his practice to avoid going to the Dallas Country Club. “I try not to go anywhere as a guest that I can’t belong as a member,” he said.

This is the side of Strauss that is usually hidden beneath the weight of his public persona. There are many famous stories about him. One is about his backyard swimming pool in Dallas. When asked by a guest why he built it, Strauss supposedly replied: “Well, at the end of a hard day at the office, I like to come home, sit out by this pool, and say to myself, ‘Bob Strauss, you’re one rich son of a bitch.’ ” He says he never said any such thing—but he loves to repeat the story.

The swimming pool story is part of his Texas legend, and at this point not even Strauss can tell fact from fiction. The rich Texas S.O.B. lives on in his imagination. When he cabled deputy secretary of state Lawrence Eagleburger last summer about needed repairs at Spaso House, here is how he described the residence: “It looks like a cross between a West Texas whorehouse and a pigsty.” The house was built in 1914 by a Russian sea merchant who entertained grandly for three years, until he lost his fortune and his life to the Russian Revolution. Since the Strausses moved in, all the rooms have been given a fresh coat of white paint and Southwestern art has been hung on every wall. As a perk of the office, ambassadors may choose art for their official residences from national museums, and Strauss chose Southwestern. “The Russians love to come here and see all these cowboy and Indian paintings,” Strauss told me, hurrying past several oils to show off his sculpture of Sam Houston. He patted Houston on the head. “This makes me feel like home.”

The four-door, armor-plated black Cadillac glided through the iron gates of the U.S. embassy and turned into heavy six o’clock traffic. From the back seat an impatient Strauss told John, his young driver, “Use the flag and use the siren, but get us through this traffic in a hurry.” The driver nodded, and soon the American flag mounted on the fender was whipping through the cold night air, cutting a miraculous path through rush hour to a large, post office-looking building that housed the newly created Gorbachev foundation.

“God Almighty!” screeched Strauss. “Look at that mob scene.” At the official opening of Gorbachev’s international think tank, large crowds of demonstrators were blocking the front of the building. Most seemed supportive of Gorbachev, but as Strauss’s driver maneuvered the car toward the front door, I noticed the police had cordoned off a small group of anti-Gorbachev demonstrators. As if the Cadillac, the flag, and the siren weren’t enough to make the American ambassador conspicuous, Strauss stepped from his car wearing a homburg instead of the typical Russian fur hat. The crowd cheered him anyway, and Strauss waved at them before hurrying inside to face yet another mob scene.

“We didn’t expect this many people,” apologized a Gorbachev aide as he led Strauss into a banquet room prepared for 250 people and now crammed with about 500. We could hear Gorbachev speaking somewhere near the front of the room, but it was so tightly packed that we could not see him. Claustrophobia closed in on me, and I was certain Strauss would not tackle the crowd. But suddenly he bolted into the middle of it. I grabbed the back of his Savile Row suit and held on to the coat as he inched us both forward. He worked the crowd as he went, speaking to about every third person, including a rabbi and many other ambassadors. The Canadian ambassador stood at a long table, sipping a glass of red wine and eating Russian canapés. “You’ll never make it up there, Bob,” he said. “Give it up.”

Strauss smiled but kept moving. It was a long, sweaty march to the front of the room, but in less than ten minutes we both stood within two feet of Gorbachev. “Hello, Mr. President,” said Strauss. “Happy birthday.” Gorbachev was in the middle of a meandering speech but leaned over to speak to Strauss during a pause for the English translation. Even though the atmosphere was festive, the former president looked somber and exhausted. He was considerably thinner and shorter than he appeared in photographs and seemed oddly uncomfortable under the glare of television lights. Beside him stood Eduard Shevardnadze, his former foreign minister, who was once a cop on the street and still carried himself with a policeman’s crisp, proper demeanor. Shevardnadze gave Strauss a meaningful nod of the head, and Strauss returned the gesture.

Suddenly Strauss’s driver appeared from nowhere with the message that Strauss had a telephone call from Larry Eagleburger. “He says it’s urgent,” John told the ambassador. “Okay, okay, I’ve done what I came to do anyway,” Strauss grumbled. Hurriedly he shook Gorbachev’s hand and then turned and started back through the masses. “I’m too old for this much fun,” sighed Strauss. “If Helen has the ice ready tonight, she’ll have done a good day’s work. God, I’m ready for a drink. ”

Back in the car, Strauss called Eagleburger in Washington. “Larry,” he shouted into the car phone, “did you call Yeltsin today?” Strauss listened to his reply. “Well, good,” said Strauss. “I just wanted you guys to make that phone call. Let’s help him out all we can.”

Strauss makes no secret of his frustration with the Bush administration’s lack of response to the critical political and economic needs of the former Soviet Union. “I don’t want to be maudlin about it,” said Strauss, “but it’s do or die over here, and because this is an election year, our policies are so damn timid.” One of Strauss’s strengths is that he knows how to function when a White House goes haywire during an election year: He lived through President Carter’s fumbling of the Iranian hostage crisis. And he knows how to cut through political inertia. “I haven’t made a phone call yet to Bush that wasn’t returned in two minutes,” Strauss said.

When Bush first asked him to take the job, Strauss’s reaction was swift and emphatic. “Are you crazy?” he asked the president. “I’m too old. I’m too busy. Let’s look for another boy.” Bush said he had considered fifty other candidates but wasn’t satisfied with any of them. “Well, the answer is no,” Strauss told Bush, but privately he told himself, “What a shame I can’t leak this to the press.”

That Bush would turn to Strauss was not particularly surprising. For twenty years Bush, Strauss, and Secretary of State Jim Baker have shared a peculiar Washington friendship that has transcended party lines. In 1973, Bush was chairman of the Republican party, and Strauss was chairman of the Democrats. In 1976, Baker was deputy chairman of Gerald Ford’s presidential campaign, and Strauss was the campaign manager for Carter’s unsuccessful run for reelection in 1979. Strauss has been on the opposite side of Bush and Baker since all three were old enough to vote. Instead of making them enemies, these political battles made them friends. “Two pols in a pod,” wrote Baker on an old photograph of himself and Strauss at a black-tie dinner that now hangs in a small receiving room in Spaso House. Near it is a photograph of Bush, Strauss, and the late senator John Tower, annotated with Bush’s good ol’ boy humor. “Visionary,” Bush scrawled beneath his own image. “Handsome and powerful” was his description of Strauss. But beneath Tower he wrote, “What’s he thinking? Three guesses!” I looked at Strauss and asked, “Well, what was Tower thinking?” “Broads, broads, broads,” said Strauss matter-of-factly.

When Bush and Strauss met to discuss the ambassador’s job, they had shared enough bad jokes and bitter campaigns to speak candidly. Bush listed the reasons why he wanted Strauss for the job: His strongest allies when it comes to aiding Russia are Democrats in Congress, the Europeans who dealt with Strauss as Carter’s trade negotiator would work with him in Russia, and most of all, Bush and Baker needed someone undiplomatic enough to tell them the truth. “This will send the right signal,” Bush told Strauss.

Strauss protested vainly. “But I didn’t even vote for you,” he told Bush. “I’ve voted against you every time you’ve run, and I’ll vote against you next time.” Bush feigned disbelief. He asked if Strauss really voted in 1988 for, as Bush put it, the other guy. “I didn’t have one bit of trouble,” said Strauss. “I just pulled that Democratic lever one time—whomp!—and it was all over. ” Bush shook his head and then told him, “Well, I guess that proves yours is not a political appointment. ”

But politics soon intervened. Whatever specific plans Bush might have had for helping the former Soviet Union evaporated when he ran into reelection trouble. Even former president Richard Nixon criticized Bush for ignoring Russia. Strauss has been left alone to manage on a day-to-day basis the low level of support that Bush did provide—almost $5 billion in credits to buy American grain, and one airlift of leftover food from the Persian Gulf War.

“Am I frustrated?” asked Strauss. “You bet I am, damn frustrated.” Privately he pushes Bush and Baker to do more, but publicly he exaggerates what little the U.S. has to give. A good example is what happened in mid-February, when American military transport planes landed in Moscow with surplus food and medicine. Baker grandly called the airlift an operation that symbolized our commitment to help freedom flourish in these new lands. But 18,000 tons of food and medicine isn’t much for 200 million people, and the paucity did not go unnoticed by Yeltsin or his critics. Yeltsin’s own vice president, Alexander Rutskoi, used the airlift as an excuse to attack democratic reforms, telling Russian newspapers it was proof Yeltsin had committed “economic genocide.”

Even the carefully planned photo opportunity almost went bust. All the media—American and Russian—had gathered for the opening of the first package of American food. As cameras rolled, one of Strauss’s top aides opened a box and fumbled through the canned goods, looking for something appropriate to show hungry Russians. With horror, Strauss watched as the man grabbed a large can of apple pie filling. Suddenly he had a clear vision of the way the story would be handled the next day: Americans tell Russians to eat apple pie. Quickly Strauss grabbed the pie filling and pushed it back in the box, then fished out a politically correct can of spaghetti. Holding up the spaghetti for the cameras, Strauss then applied his own spin to the airlift story. “Now I know this is not a lot of food to have,” he told reporters, using his best down-home bull, “but it’s a lot to want. Besides, this is only a small gesture, not much more than a symbol, really, of what we hope to do in the future.” Strauss knows how to send a message and, even more important, how not to send one.

No one could mistake him for an ordinary diplomat. One night he and Baker went to dinner at the home of Nursultan Nazarbayev, the president of the oil-rich republic of Kazakhstan. Small jiggers of vodka were passed around with the customary toasts, followed by a four-course meal that lasted until one in the morning. Just when Strauss thought the long evening was finally finished, the president suggested that Strauss and Baker join him in a traditional Russian steam bath. They all walked about a block down the street to the bath, took off all their clothes, and soon were sweating vodka. As attendants pounded them with birch branches, the president asked for advice on how to broker energy deals with persistent U.S. oil companies. There was a long, uncomfortable silence until Baker explained that under U.S. law, neither he nor Strauss was allowed to discuss energy, since both have financial interests in oil and gas wells.

“The president must have figured us for a couple of boobs,” said Strauss. “Here he has two naked Texans in his steam bath, and we tell him we have to recuse ourselves from oil and gas because we happen to know something about it.” Strauss resolved never again to be caught in such a situation. The next day he telephoned Eagleburger at the State Department and asked for a waiver so that he can discuss energy with both Russians and Americans. He got the waiver within 24 hours. “I told Larry he needed to play me or trade me,” said Strauss. “Now I talk about energy with anybody I want. ”

In his tiny office at the American embassy, Strauss, wearing a pale yellow sweater, sat behind a plain mahogany desk and stared longingly out the window at a narrow snow-covered alley. “It’s kinda like a prison, isn’t it?” he asked. Beyond the alley, but still in the embassy compound, is a red-brick eight-story office tower, infested with Soviet listening devices, that now stands vacant and useless. Strauss’s office is furnished with only a desk, a round table, and two seashore paintings on the wall to his left and right. It is easily the most modest work space of his lucrative adult life, seven thousand miles from the luxurious law office he left behind in the center of Washington.

His day begins about six-thirty, when he fixes his own breakfast—usually grits and rye toast—in the upstairs kitchen at Spaso House. He spends at least two hours alone, reflecting on the day ahead. “The rest of the time I just react,” said Strauss. “But I’ve always taken time in the morning just to think.” Usually he arrives at the embassy at around nine and works until about seven in the evening, then goes back to Spaso House for his sacred nightly cocktail with Helen. Often he entertains people for dinner but retires to his upstairs study at ten to start making telephone calls back to the United States, where it is early afternoon.

On this particular Tuesday, Strauss’s first appointment of the morning was a tall, studious man named Andrew Natsios, an administrator for the Agency for International Development (AID). Natsios walked through the door, sat down, and told Strauss he had good news. “We’re prepared to give thirty million dollars to help farmers here and an additional twenty million dollars in medical assistance,” he announced. When he paused to breathe, Strauss jumped down his throat. “I want you to know,” said the ambassador, leaning across the round table, “that’s chicken feed, nothing but chicken feed. ”

Natsios’ jaw dropped for just a second, but he recovered quickly and was soon in Strauss’s face. “Well, Mr. Ambassador,” he shot back, “it’s twenty percent of our total budget.” But Strauss would not let him continue. “Look, we really want to get our hands on your money in the worst kind of way,” said Strauss. “We need your help here, and we must have it now.” Natsios then launched into a tedious description of how his agency could offer detailed technical assistance in distributing the money. Strauss’s eyes hardened to a glaze. The ambassador stood and whisked the young man from his office with a flurry of pats on the back and thanks-for-coming coos.

As ambassador, Strauss has three main constituencies: Bush and his foreign policy, Yeltsin and his government, and American businessmen who are trying to negotiate deals in Russia. His approach to all three is the same as his treatment of the earnest young man from AID: Pound on the desk until he gets what he wants.

Since his arrival in Moscow, Strauss has turned the embassy upside down. “When I first got here, an American businessman couldn’t even come into this place for a meeting,” said Strauss. “If the Reverend Billy Graham, Mother Teresa, David Rockefeller, and a thirty-dollar hooker all showed up at the front gate at the same time, they all got turned down for the same reason: They were security risks.”

His first blow against the cold war mentality was to change the no-guest rule to allow Americans access to their own embassy. Soon business leaders such as Jack Murphy, the chairman and CEO of Dresser Industries, who has traveled to Russia for the past twenty years, had their first peek inside the embassy compound. Next Strauss changed the rules about one-on-one meetings between embassy employees and Russians. For the past decade, Americans posted in Moscow were forbidden to meet with individual Soviets, and if such meetings took place by accident, Americans had to document whether it was business or pleasure. The rules—which Strauss called an insult to both Russians and Americans—were adopted after various spy scandals, including one in which a Marine divulged secrets to his Russian lover. “We’re trying to get rid of these leftovers from the cold war,” said Strauss. “Now my secretary can go out to dinner with her Russian tutor if both women choose to do so.”

When he read the fine print of his budget and discovered that it costs $175,000 a year, including salary, transportation, and other hidden expenses, to have an American janitor sweep the streets inside the embassy compound, he asked permission to hire Russians to do the same job for $1,400 a year. Baker said yes, and Strauss went home that night feeling as if he’d struck a small blow for liberty.

Compared with the dimly lit stores and offices in Moscow, the fluorescent lights of the embassy seem blindingly bright. The embassy has a beauty shop, a post office, a bank, the Liberty bar, and its own small store—not much bigger than a 7-Eleven but stocked with M&M’s, Baby Ruths, peanut butter, cornflakes, and additional comfort food from home. The central meeting ground, however, is the embassy cafeteria, which serves food flown in from Helsinki: baked chicken, meat loaf, fresh vegetables, all things you can’t get outside the gates.

Strauss eats at the cafeteria so often that employees feel comfortable enough to tease him about his politics. “You better be nice to me,” joked a female construction worker from Bechtel Corporation, “or I’ll vote for the Republicans in November. ”

Much of Strauss’s time is spent managing the five hundred full-time employees who work in the embassy. Many live in the 132 apartments inside the compound. Theirs is a closed, incestuous world where everyone knows the details of everyone else’s lives. “This is a real hothouse,” said Strauss. “They all live crammed up here together. It’s not healthy.” When Strauss heard that security officers had refused to allow one employee to bring his six-year-old daughter to the office with him on Saturday afternoon, he hit the roof. “I called twenty of my top aides together and told them to go home at seven as often as possible, have a drink with their wives, and spend some time with their families,” Strauss said. Apparently he is not exaggerating the family problems. “How Does Living in Moscow Affect Your Relationship?” asks an advertisement for an upcoming marriage workshop tacked to an embassy bulletin board.

Strauss is most at ease when selling capitalism to the Russians. He regularly appears on Russian television to give mini-lessons in economics. “Borrowed money compounds interest,” he often tells TV audiences in Moscow, “but invested money stays in the ground and will grow.” Implicit in this pitch is the idea that Russians should welcome foreign investors, especially Americans. But sometimes his image as a dealmaker gets in his way. “I get so tired of this idea that I might personally profit from any of the deals I push,” said Strauss. “Hell, if all I wanted to do is make money, I do that best from Washington.” In order to satisfy critics, Strauss sold his interest in the Dallas-based law firm he founded in 1946, now known as Akin, Gump, Hauer, and Feld.

Moscow today is a bizarre bazaar. Across the street from Red Square, a large neon sign screams advertising in English for a new securities trading house called Russia House. Western hotels are crowded with Japanese, German, Italian, British, and American businessmen, some of whom are—as Strauss put it—“the greatest collection of sleazebags in the world.” Some are shopping for nuclear bombs; some want to get rich quick off the country’s timber and oil. The only sure deals are made with the Russian whores who operate out of the best hotels and trade only in hard currency, not rubles.

“This is the Wild West out here,” said Strauss. “I often tell people it’s like the old Texas oil-boom towns, a constant parade of con men, promoters, and shady customers.” Usually Strauss fends these types off (“I can smell ’em,” he brags), but occasionally one slips through. For instance, not long ago a well-meaning staff member brought in to see Strauss an American oilman who was bidding on a lease. He also brought the government official who would soon be awarding the contract. “Now wait a minute,” said Strauss, pointing at the businessman first. “Aren’t you a bidder? Aren’t you awarding the contract?” Both men shook their heads yes. “Well, before we all get hauled before the Senate ethics committee,” bellowed Strauss, “get the hell out of my office.”

He tries to focus on bigger problems, such as how to help Yeltsin restructure the enormous external debt incurred under Gorbachev and how to get the Russian ruble converted to hard currency. The price of bread has risen from less than 1 ruble to 4 rubles, butter from 50 to 150 rubles, the price of a subway ride from 6 rubles in February to 60 the first week of March. The official exchange rate was 100 rubles to the dollar. The higher prices are Yeltsin’s most immediate political problem. “I told him six months ago that he ought to name himself a prime minister,” said Strauss, “so he’d have somebody to fire when people got mad. But he decided to take the heat himself. ”

I have an important announcement to make,” said Strauss, standing before a group of sixteen representatives of the world’s biggest investment banks during a breakfast meeting at Spaso House. The banquet hall grew quiet, and the men shifted to the edges of their chairs. Would the ambassador pass along information from Yeltsin’s inner circle? Did he have the latest news from Washington? “I rose to tell you,” said Strauss, with a theatrical pause, “that we have oatmeal here at Spaso House.” In Russia today, business cannot begin until the issue of food is settled.

Strauss had invited the bankers to come to Russia at their own expense to look at possible investments. Over the next three days, Strauss and his staff would show them business proposals for fourteen cities. “The truth is, fellas, we’re behind,” said Strauss. “People over here don’t really think that well of Americans. They see the Germans, the British, and the Japanese over here doing business, and they wonder why we’re not here too.”

He was not overstating the problem. Much of what the ordinary Russian sees of democracy is not pretty: high inflation, fixed wages, and the most visible sign of all, the flea markets. Russians stand on the street in front of state stores, selling whatever they had managed to hoard before the revolution. The first week in March, a pair of jeans sold for around 75 cents in a flea market that formed in front of Detshii Mir, the largest toy store in Moscow. I saw a purple telephone for sale, a can of American hot dogs, and many yellow-haired dolls. I stopped to ask a woman the price of her box of crayons. “Eighteen rubles,” she answered. “Twenty in the state stores.” The atmosphere in the flea market is grim, but occasionally you hear a joke. “How much for that box of macaroni?” asked a buyer. The seller quoted a price that must have been too high. “Then how much for just one piece?” he asked. They both laughed at their common misfortune.

“This is not serious business,” said my translator. To her, a flea market is only a public black market. But in fact the impromptu markets are an accurate measure of Russia’s slow progress toward a real free market. Most Russians are now living in the shadow of democracy, holding on to their old ways while venturing toward the new and unknown. An example is Alexander Bondarchuk, a construction worker whom I happened to meet through my translator. Alexander and four of his friends recently leased a small factory on the banks of the Moscow River. There they build tables, chairs, and bedroom furniture from Russian pine while looking for Western partners to sell their furniture abroad. “Until then, we sell to Russians,” said Alexander. “No matter what happens to the government, people will still need furniture.”

It is small businessmen like Alexander who will determine whether democracy lasts in Russia. If he attracts the right kind of foreign investors, his business will flourish. However, he could just as easily attract a partner who is still waging the cold war. “I’m here to rape this country,” I heard a New York aluminum trader say. “I want to get what I can get and get out. ”

That attitude is what the investment bankers were brought to Russia to counteract. “We haven’t won a damn thing out here yet,” Strauss told them. Then he described the magnitude of the problem: Yeltsin is under constant attack from midlevel bureaucrats who want to see his economic reforms fail. Meanwhile, hundreds of thousands of Soviet soldiers are walking around Moscow all but homeless. At night they sleep thirty men to a tent and blame Yeltsin for their mistreatment. “This country is more chaotic and in worse shape than it was sixty to ninety days ago,” said Strauss, “but it’s a great deal better than I thought it would be.”

Strauss believes Yeltsin is the only hope for stability in Russia. “There is no one else,” he told the bankers. That’s why he has regular meetings with Yeltsin and stays in daily contact with the small group of ministers who are implementing Yeltsin’s reforms. Strauss and Yeltsin hit it off the first time they met. Yeltsin asked Strauss what he did for leisure. “I like to come home after a hard day’s work and fix myself a couple of drinks,” Strauss told him. “What?” asked Yeltsin. “No ladies? No girls?” Strauss grinned. “Mr. President,” he said, “I like to play at poker, work at my job, but only look at pretty ladies.”

Poker is as good a metaphor as any. Yeltsin is playing for the highest stakes and has bet everything on his economic reforms. So far the U.S. is not really in the game, but it has a small side bet on Yeltsin. Strauss is rooting Yeltsin on and giving him advice at the same time, while trying to get Bush, Baker, and now the investment bankers to quit kibitzing and get in the game. The bankers seated at the three round tables at Spaso House have the power to ease Russia’s chaos. Strauss asked them to ante up: first, to help get Russia into the World Bank, and second, to bring pressure on Bush to provide a stabilization fund so Russia’s economy can begin a recovery.

“We’re in an election year,” Strauss told the bankers. “That means our public policy is weak. It’s up to you guys to push these things through.” Next he gave them a quick lesson on how to deal with Russians. “Don’t be timid,” he bellowed. “Tell ’em what you want.” Then he suddenly remembered his role. “Remember not to offend anyone,” Strauss said. “God knows, I’m the diplomat.”

- More About:

- Politics & Policy

- TM Classics

- Longreads