This story is from Texas Monthly’s archives. We have left the text as it was originally published to maintain a clear historical record. Read more here about our archive digitization project.

True Confessions

On Wednesday, August 1, 1973, the La Grange Chicken Ranch, the Oldest Continually Operating Non-Floating Whorehouse in the United States, was closed down. The Texas Chamber of Commerce elected to ignore the passage of an establishment possibly older than all its members; and the State Historical Society, equally misfeasant, overlooked the shuttering of the house that slept more politicians than the Driskill Hotel and the Governor’s Mansion combined.

You all know about the Chicken Ranch of course. It was just about the first tourist attraction I heard about when I came to Texas. But, then, I came to Texas to be an Aggie, so that explains that. Later on I even learned that there was a town called La Grange nestled somewhere on the outskirts of the whorehouse of the same name.

Hell, I even went to La Grange once. The whorehouse, I mean. Not, mind you, because I had any truly unquenchable perversions that required a trip to La Grange to unleash, but, rather, because I figured that if one was going to be an Aggie, well then, Be An Aggie. The pilgrimage to La Grange sits close to the heart of The Aggie Myth, as central to the catechism as standing at football games and building the Bonfire for the Texas game.

We went on Thursday night when they had the $8 Aggie Special, trekking down in an old Pontiac full of fraudulently-purchased Lone Star and a thousand obscene variants of some drastically original horny Aggie fantasy.

We circled around town for a while, body temperature rising in inverse proportion to the declining stash of Lone Star and the increasing depravity of the fantasy, a deep, twisted well of prurient anxiety gradually filling to the point where no adolescent squeamishness could possibly abort an explosive gusher of Sinful Lust.

How’s that for metaphor? eh? Us Aggies get a three-syllable handicap in this magazine-writin’. In any case, the air went out of the fantasy as soon as we pulled into the Chicken Ranch parking lot and the first person we spotted was a deputy sheriff. He was just there to help park cars, though, so we proceeded on up to the door where Lilly, the black maid—the only black as a matter of strict fact (historical accuracy being an important part of articles like this) who ever passed the doors of the Chicken Ranch—checked our phony I.D.’s to make sure we were 21 and let us in.

We sauntered into the parlor where we drunkenly introduced ourselves to a half-dozen local farmers, a couple of cross-country truck drivers, and a fellow pilgrim who’d journeyed all the way down from Nebraska—and met three young ladies who either worked there or were truck drivers, too, we weren’t sure which.

One of the young ladies offered to sell us a Coke for 50 cents, which we declined, and then one of her friends asked us for a quarter to play the jukebox, which we cheerfully provided. My friend Richard, who was still trying to decide if they worked there or were just visiting truck drivers, thought he’d break the ice a little by asking one of them if she wanted to dance, which she didn’t.

“What’s with this dancin’ stuff, honey?” is what she said. “Ya wanna do some business here or not?” That’s when we decided she must be one of the U.T. coeds we’d heard about.

Pretty soon after that I picked one of the ladies (or she picked me, quite possibly, my recollection being sort of hazy) and we wandered off down the hall to one of the bedrooms. The walls of the room possessed an angularity that bespoke distracted carpentry, all of them covered with irregular splotches of pastel paint, and the furnishings consisted of a bed, a dresser and a sink, all rather commonplace in appearance and not at all meeting my expectations.

The top dresser drawer had been left open to reveal an intriguing assortment of oils, photographs, and leather goods, but I held firm for the Aggie Special which didn’t include any of its contents. Ruthie, who was the lady I’d picked (or who’d picked me), just rolled her eyes and made a face when I told her I only had the eight dollars anyway. She told me to “Git yer clothes off, honey,” and left to go deposit my money someplace.

I thought for a bit about how this wasn’t the way we’d planned it on the way down and was consequently a little slow getting undressed, being still garbed in my pants when Ruthie got back. “What’s this?” she asked me. “We ain’t got all night ya know.” I apologized for being so slow and took my pants off.

She then started poking and tugging at me, “checkin fer diseases,” she said, a bit of foreplay that possessed all the sensuality of my Army physical. Ruthie next threw me down on the bed, took off her own clothes and lay down beside me, and told me that for just eight dollars I didn’t get to kiss her.

Pleased that I hadn’t brought any more money, we just started pawing and pulling at each other and, next thing I knew, she was on top of me and asking if I was “finished already, honey?” “Well, uuuh . . .” I said. Then she pulled me up off the bed, washed us both off, and told me ta “git yer clothes back on, honey.” It had been what’s known in the trade as a “Four-get”: Get up, Get on, Get off, and Get out.

I met the rest of my cohorts outside, all except for Richard for whom we had to wait another hour and a half. He’d been so abased at being turned down for his dance that he’d gone and splurged $40 on a lavish degeneracy of sufficient novelty that its graphic description entertained us all the way back to College Station.

A Sentimental History of America’s Oldest Whorehouse

When old Frank Lotto published the first History of Fayette County back in 1902, he wrote, with what must have been a sly snicker to himself, that “The City of La Grange has made a reputation for sociability over the whole state.

It was nicely located for friendly ambience, being sprawled around high limestone bluffs on a parabolic stretch of the Colorado River in that part of Central Texas where the coastal plains begin gently ballooning into a sinuous undulation that goes westering off to the Hill Country. Dense battalions of age-disfigured live oaks, camouflaged in clouds of hanging moss and sentried by towering cedars, occupy the creek and river bottoms while post oak columns skirt the soft green edges of Bermuda Grass hillsides and cypress files demarcate the boundaries of old Spanish land grants. The Second Congress of the Republic of Texas, enticed by vistas “that but few countryes on Earth can compare with,” overwhelmingly voted to establish their permanent capital at La Grange, and only President Sam Houston’s self-serving veto kept it in the still-unbuilt jerkwater burg named for himself.

If the easy-rolling richness of Fayette County posed no strong attraction for General Sam, it proved a powerful lure across the world in Central Europe. Beginning in the 1830’s it became the terminus for South Germans and Bohemians in flight from famine and persecution. They brought with them an industrious capacity for small farming, which still endures, and an independence of mind bordering on the perverse, which also still endures. Ever since 1860, when they voted not to secede with the rest of the state, Fayette County has maintained a strong tradition of political aberrance.

The immigrants also imported a zesty beer-hall enthusiasm for rowdy pleasures. Indeed, nothing in the county’s history has proven so consistently unpopular as Temperance, which went down to its first massive electoral defeat in 1877. It was the kind of indulgent tolerance that could sanction the longest-running brothel ever to open its doors and beds in America.

Just when exactly those doors and beds did open is a point of some contention. Dates offered range all the way from 1844, based largely on myth, to 1915, when the house was installed in its present location on the outskirts of town. The most likely occasion for its founding is somewhere in between, with several La Grange oldtimers remembering its definite existence prior to the turn of the century. Ernest Emmerich, who was town marshall in neighboring Round Top back around the First World War, remembers then-County Sheriff August Loessin telling him it was there when August took office in 1894.

The debate, in any case, is spuriously academic. Just as a history of North America, despite its prior existence, doesn’t really commence until Columbus, so the True Story of the Chicken Ranch doesn’t begin until the arrival, in about 1905, of Ms. Faye Stewart, alias Jessie Williams, and known to friends, employees, numerous intimate acquaintances and elusive Posterity as Miss Jessie.

Originally from Hubbard, up near Waco, Miss Jessie was a whorehouse madam on an epic scale, prostitution’s answer to Casey Stengel or Vince Lombardi, author and actor is one of the great chapters in the journal of her profession. A woman of undeniable personal resonance, with rough-hewn country charm and shrewd backwoods tenacity, she is still discussed with soft-eyed affection and reverential tones by those who knew her.

Buddy Zapalac, the editor of The La Grange Journal, says, “She just had ta be one a the most amazin’ women who ever lived. She was strong! But she was generous, too. And whoooh, Boy! but she was a smart one.”

It was Miss Jessie who somehow brought discipline and profit to the house while making peace with the surrounding community at large and its power center in particular; she also negotiated the tacit treaties that enabled her house to survive in the face of contradiction and indignation, a diplomatic performance rivaling those of Henry Kissinger.

Among the first allies she acquired were the Loessin brothers, August and Will, the former being County Sheriff and the latter, younger, being at once the City Marshall in La Grange and his brother’s chief deputy (and later his successor as Sheriff). Widely venerated as peace officers, the brothers Loessin seem genuinely to have been well-respected and able peace-keepers, August being the only Central Texas Sheriff to crush the Ku Klux Klan during its bloody pre-War resurgence and Will earning a statewide reputation for ingenious detective work.

The early basis for their pact with Miss Jessie seems to have been a kind of mutual coexistence. She foreswore many of those sidelines that would seem natural in a country cathouse, liquor most notably, and operated it as peaceably and businesslike as the Post Office. The two sheriffs, for their part, just ignored it.

It was a beneficial relationship. Miss Jessie prospered and, in 1915, she abandoned the battered downtown hotel they then occupied, and moved her business to the southeastern outskirts of town. She brought in a few new girls as well, including two sisters who learned their craft in the break-hell East Texas oil boom and were to serve as middle-management. The house was by now rooting itself into the communal fabric of La Grange and its resident employees, encouraged by Miss Jessie to stay on a permanent basis, had fashioned a broad array of links with the townsfolk; when the boys from La Grange went overseas to Save Democracy in The Great War, the girls from the Ranch sent them cookies.

Soon after the end of the War, Will Loessin was elected to succeed his brother. At some nebulous, earlier point he had made a discovery that struck a glorious chord in his detective heart, one that would repercuss down through all the following years of Fayette County law enforcement. This was, in essence, that men, significantly including local lawbreakers, are (1) habitually prone to bursts of braggadocio, often self-incriminating and helpfully revealing, when they are in bed with women, and (2) these same men were regularly inclined to go to bed with women out at Miss Jessie’s. Wonder of Wonders! Will Loessin, in one of the grandest strokes in the annals of detectivery, had buried deep in the twisted solar plexus of the criminal element an incredibly Organic Wiretap.

And Miss Jessie, not disinterested in further cementing her alliance with the forces of justice, was graciously amenable to stepped-up cooperation. From thence forward, continuing on through all of his 26 years as County Sheriff, Will Loessin would journey nightly out to the edge of town to visit with Miss Jessie and learn what intelligence may have been ferreted out by this subtle pack of eavesdroppers.

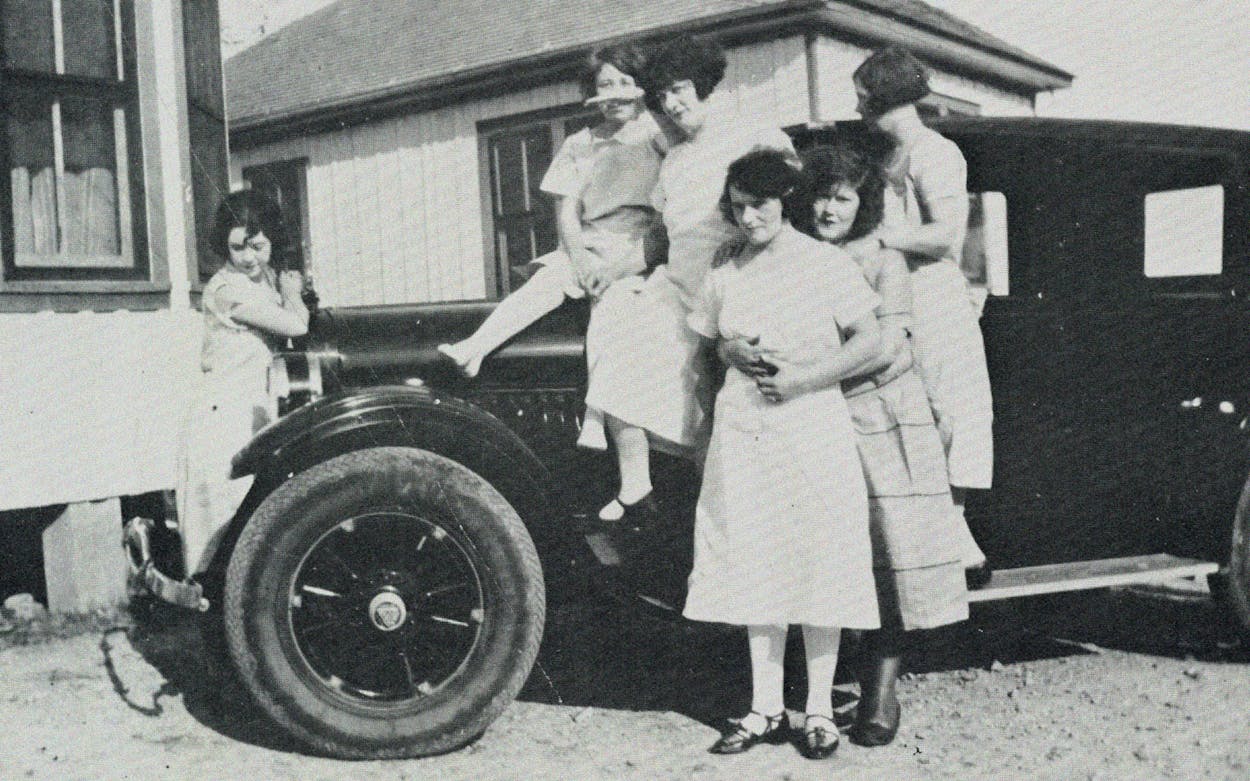

The Ranch itself was undergoing a little facelift about this time. Not only had Miss Jessie added on a couple of rooms to accommodate her burgeoning flock, but the Gilded Age of post-war ebullience was sending liberating vibrations even unto the outskirts of La Grange. The girls acquired shiny new cars and flapperish regalia, the rooms received new paint and overstuffed furniture, frenetic snatches of jazz were caught drifting through the woods, and Miss Jessie’s unpretentious country whorehouse almost became a bawdy citified “sporting house” as it passed through the gaudiest phase of its lifetime.

The emancipation of the Ranch, though, did not include any creatively expanded repertoire of available pleasures. Waco-bred Miss Jessie had always looked with fundamental distaste on all possible erotic combinations that went beyond the dully conventional missionary position, and the continentally-whetted appetites of war-returned farmboys made her furious.

One La Grange oldtimer, a thrice-weekly regular back in those days, remembers trying to explain to a girl named “Deaf” Eddie how to navigate one pleasantly intricate movement: “See, we called ‘er Deaf Eddie cause she really was harda hearin’, so I was havin’ ta talk purty loud. Well, whut hoppened is thet Miss Jessie heard me an come acrashin’ inta there hittin’ me with a big iron rod and hollerin’ ’bout turnin’ her girls inta French whores. She throwed me out an’ wouldna let me back fer a month.”

Prices at Miss Jessie’s then were on an easily computed sliding scale based solely on the time consumed, climbing from $3 up to about a $40 maximum, and not until years later did other variables serve to complicate the equation. The only disruption of these simple accounting procedures came with the Great Depression, when rural economies collapsed into a chaos of barter and salvage.

Miss Jessie, whose Depression-sparked social consciousness would make her one of the fiercest New Dealers in the county, promptly adjusted to the new market by accepting payment in farm produce at the straightforward rate of one chicken, one screw. The backyard was quickly over-run with scratching and fluttering Dominickers and Rhode Island Reds, and the heretofore anonymous whorehouse became the Chicken Ranch.

Thus christened, the Ranch passed quietly through the rest of the decade, the only disruptions caused by a rare and foolish Republican who had the temerity to challenge Miss Jessie’s estimation of Franklin Roosevelt.

The Ranch was by then thoroughly imbedded in the webwork of life in Fayette County. Miss Jessie contributed money to local civic clubs and church bazaars, establishing the policy of municipal philanthropy that in later years would see the Ranch become the largest sponsor of the Little League. And, while stopping short of joining the Jaycees, Miss Jessie manipulated capital expenditures in a way that best suited everyone, not excluding herself. Deliveries from groceries, hardware stores, dairies, five and dimes, all were rotated on a weekly basis so that each would receive their share of the Ranch’s business.

Early in his tenure, Will Loessin had begun the tradition, which continued on up to this year, of reporting on conditions at the Ranch to the twice-annual Fayette County Grand Jury. Estimates of revenue, reports on fights or arrests or information learned were all provided, and an occasionally rambunctious Grand Jury would troop on out to see for themselves, Miss Jessie pleasantly showing them around. In later years, girls going to work at the Ranch would stop first at the sheriff’s office to be mugged and fingerprinted, so that checks could be run to see if they’d ever done something illegal somewhere.

One of those early Grand Juries began the practice of requiring weekly medical exams for the girls at Miss Jessie’s, and the office of County Medical Examiner was created solely for that purpose. In more modern times, after the office was abolished, the girls would appear every Thursday at the La Grange Health Clinic to have their non-contaminatory status officially certified.

When America found itself in another war in 1941 and a second generation of Fayette County farmboys left to participate, the girls at Miss Jessie’s again sent cookies and wrapped bandages for the Red Cross. The Army moved in a training center at nearby Bastrop and, apparently concerned that indiscriminate whoring might short-circuit the American soldier’s innate killer instincts, launched a wide-ranging campaign against prostitution. Life at the Ranch temporarily became a little more circumspect, but the officially subversive operations went unimpaired for the duration.

The end of the War brought, amidst other happenings, the retirement of Will Loessin; his replacement, ascending almost mechanically into the vacancy, was T. J. “Jim” Flournoy, who had been Will’s chief deputy for a dozen years before putting in a stint as a Texas Ranger. In the same inevitable manner that a national administration will assume the accumulated allies and obligations of all its predecessors, Jim Flournoy inherited all those instinctive understandings and tacit pacts that Miss Jessie had forged 40 years earlier with the Loessin brothers; the momentum of the Ranch swept past another milepost without a missed step or a side glance.

Some of that feisty energy that had driven her thus far had begun to subside, though, and, while post-war prosperity was acknowledged in the form of a couple more tacked-on bedrooms, the attendant post-war exuberance inspired no response at the Ranch. They just settled a few years earlier into that semi-moribund inertia that captured the country through most of the fifties.

Miss Jessie, wheelchair-bound in her last years, watched the decade turn from the front porch of the Chicken Ranch, still firmly in command and admitting respect for no one since Franklin Roosevelt. She died, Faye Stewart died, in 1961, mourned by many who were too embarrassed to demonstrate it and missed by four generations of men whose passage from innocence she had administered.

She had, moreover, wrought permanent change in the world she occupied: her Ranch, at some ephemeral point in its passage through the years, had transcended its role as merely a whorehouse to become an Institution, as important a work in the Gallery of Texana as Spindletop or San Jacinto. The Whorehouse at La Grange had passed mouth-to-ear through the locker-room memories of four generations of Texas men, and its widespread acceptance was tacit acknowledgement of its new status.

The Texas Legislature made reference to it in light-hearted floor debate as early as the forties, and Miss Jessie returned the compliment by amending her cash-only policy to include the acceptance of state payroll checks. Books, magazines, and newspapers all wrote sympathetically of its existence and, as the sixties appeared, adventuresome students would make it a topic for term papers and masters’ theses.

Indeed, if the Chicken Ranch is viewed strictly as an illegal brothel, then the largest part of the State of Texas was for 20 years involved in a cover-up of unmatched proportions. More likely, the Ranch had passed beyond reach of The Law into another, more sentimental, dimension where The Law serves no purpose.

Miss Jessie was to be succeeded by a woman as thoroughly schooled for her role as Jim Flournoy had been for his. Edna Milton had come to work at the Ranch in 1952, and by the time Miss Jessie died was chief lieutenant in the management of the house. Red-haired and tough-skinned, with clear-green Laser-piercing eyes, Edna evokes an authoritative confidence that could as easily run a Teamsters local as a whorehouse.

She arranged to purchase the Ranch from Faye Stewart’s estate and installed herself as madam, moving into the master bedroom that still contained Miss Jessie’s massive four-poster walnut bed. To all appearances the house absorbed the shift in management as effortlessly as it had the paper alteration of ownership, the only real changes being the installation of air-conditioning and the offering of a limited variety of “exotic extras.”

Edna, even before Miss Jessie died, had been in charge when the Ranch weathered its greatest crisis: Texas Attorney General Will Wilson, who wanted to be a U.S. Senator, had sounded the call for a great moral crusade aimed vaguely at making the state safe for the easily outraged, who presumably form an impressive bloc of voters.

State law enforcement officials were dashing hungrily around on the hot trail of sin, very nearly arresting the entire island of Galveston, and it seemed likely that the Chicken Ranch, as the state’s most notoriously renowned whorehouse, would be a sure target.

Edna’s response was to go underground, making the pretense of shutting down while admitting regular customers through the back door. It was good enough. Like all crusades, Wilson’s choked on the heat of its own righteousness and he soon went away. The Ranch slipped back into a normal high gear and went humming along into its future, sweetly indifferent to muffled indignation or pious politicians, prepared to cope when necessary with the inevitable next crusade.

The next crusader, though, would come armed with cameras.

The Electric Bounty Hunter Meets the Nightmare Sheriff

Marvin Zindler was a public curiosity [See “Marvin Zindler, Consumer Lawman,” TM February, 1973] even before he became a nightly refutation of McLuhan’s thesis that television is the province of the cool. Marvin is most assuredly not cool, and never has been.

Back when he was heading the Consumer Protection Division of the Harris County Sheriff’s Department, he would inveigh against truthless advertisers or fast-dealing car salesmen with all the indignant wrath of a Calvinist preacher accosted in the pulpit by some hot-eyed, leering flasher. And always with an audience. Marvin Zindler was to huckstering what Jehovah’s God was to sin, with the exception that Marvin always had cameras there to record the pointing of his vengeful finger.

He had a fair penchant for attracting attention. Stories used to float around the city rooms of Houston newspapers about how Marvin would wait two and three days before serving a warrant until a TV crew was available to immortalize his crimebusting; about how Marvin would deluge courthouse reporters with Agatha Christie-style press releases extolling his exploits; about the time The Houston Post, on Marvin’s “hot inside tip,” bannered the four-inch headline HARRELSON IN MEXICO at the same moment the accused murderer was being arrested in Atlanta.

Back when he was the police reporter for a Houston radio station, Zindler would appear just before his on-air signal to relate action-packed on-the-scene accounts that he’d just read from the morning papers. Other reporters used to substitute dated papers and he’d dash in to announce, over the air, “This is Marvin Zindler, On The Scene . . .” and launch into a breathless blow-by-blow of last month’s liquor store holdups.

Zindler even looks the part, which is to say artificial. His nose and chin were metamorphosed long ago to meet superstar specifications, and his head is permanently hidden by a handsome Cary Grant toupee. And his clothes, equally handsome, are custom-tailored to conceal the pads he wears on his shoulders and buttocks to fill out his figure to superstar proportions.

It’s always been easy, of course, to make fun of Marvin Zindler, as do most of his colleagues in journalism. But, strangely enough, it just won’t wash. For one thing, he’s so obsurdly up-front about those wigs and pads and nose-jobs of his, and he confesses instantly, cheerfully, to a raging egomania. It’s hard to laugh at somebody’s closet skeletons when they rattle them at you.

And then there’re his eyes, as warmly blue and gentle (and genuine) as any superstar could hope to possess, the only external hint that within that ludicrously handmade body of his there’s a soft nub of sincerity and compassion.

Danny, who’s sort of a hustler, remembers being arrested by Marvin way back when he was just another deputy in the Warrants Division: “Most of the crooks I know have a lotta respect for Zindler. He was a straight-up cop. After he’d busted ya, he’d stick around till ya were mugged an’ printed an’ in the tank, an’ he’d make sure ya had cigarettes before he’d leave.”

He still shows that same concern in his role as Channel 13’s consumer affairs reporter, staying long after work to answer a blizzard of phone calls from 12-year-olds with lost bicycles and dowdy matrons who don’t like the gas company. He rationalizes his media-mongering by saying “Most corporations involved in, say, false advertising will just laugh at a $50 fine, but if you show up with a TV camera and give ’em bad publicity then they’ll shape up.”

There’s a hard truth there. If Marvin’s style, a zany blend of P. T. Barnum and Dudley Do-Right, has made him notorious, it’s also made him effective; instead of being just another petty public ombudsman, he’s become a kind of Electric Bounty Hunter, striking Media-Terror into the fast-talking hearts of consumer bilkers.

That’s why it all seemed a little strange when Marvin set out after the Chicken Ranch: while there may well be lots of people who don’t like the place, irate consumers aren’t among them. But Marvin says his crusade against the Ranch wasn’t based on any righteous shock at all the whoring going down out there. “I’m no moralist,” he’ll tell you. Marvin’s targets were bigger than just sin: political corruption and Organized Crime.

Marvin’s story is that he got his hands on a Department of Public Safety (DPS) intelligence report that had been made last year. This report, according to Marvin, says that the Chicken Ranch—together with another, less reknowned, little whorehouse in Sealy—grosses “a conservative minimum” of $3 million a year, and that most of this money was going into numbered bank accounts in Mexico by way of lavish payoffs to all manner of corrupt state and local officials. It’s these officials, the story goes, who really own the Chicken Ranch and whose power in Austin allows it to stay open.

Then there’s the black specter of Organized Crime, whose ruthless involvement Marvin keeps invoking. Marvin’s definition of Organized Crime, though, is not exactly what you’d first think. It has nothing to do with the Mafia. Or the Syndicate. Or Chicago or New York or even Houston. It maybe has something to do with a “circuit” of other country whorehouses through which girls are rotated, but it’s hard to say. Marvin’s definition of Organized Crime is pretty vague.

Nonetheless, Marvin bought this DPS report at face value, lock-stock-and-brothel. He has great faith in the Texas Rangers.

When he first saw the report last January, he says, he was asked by the Rangers not to do anything until they’d had the chance to “move in.” Marvin agreed. Then, along about May, Marvin got word that the DPS-Ranger investigation had been canceled. “That’s when I really got mad,” remembers Marvin, “cause it proved to me that somebody from higher up was interfering with the enforcing of the law.”

That’s when Marvin went to work. He recruited as his collaborator Larry Conners, a young TV newsman who is a first-rate investigative reporter and the most hard-ass interviewer this side of Mike Wallace. The Zindler and Connors team went underground to begin their investigation.

They sat in the woods outside the Ranch counting and photographing the patrons. Conners, together with a cameraman (but, sadly, no TV camera) handled the “inside work,” discovering first-hand that there really was prostitution going on in there.

After three months of this sort of thing they were able to prove that, sure enough, there’s a whorehouse in La Grange. That’s when they broke the story and ran up against, or into, County Sheriff T. J. “Jim” Flournoy.

Old Jim Flournoy looks like he leapt full-bodied from one of Bobby Seale’s nightmare visions of a county sheriff, a pot-bellied, gun-totin’, hulking incarnation of Frontier Justice. Slow-talking, in keeping with his thought patterns, Big Jim’s style of dealing with the world is based largely on Threat, and is generally successful. His brother Mike, who is the sheriff over in Wharton County, has a reputation for carrying out his threats, but big Jim’s never gone overboard with that sort of thing.

Like his predecessors, Big Jim was easily accommodated to the existence of the Chicken Ranch. Back in 1958 he’d even had a Hot Line installed to connect the Ranch and the Sheriff’s Office, and he’s one of the biggest defenders of its operations. “It’s nevrah caused no trouble round here,” he says, “no fights or dope or nothin. I ain’t nevrah got no complaints.”

It’s been a positive boon to law enforcement, if you listen to the sheriff. Because of the Ranch, “Thar’s nevrah been no rapes while I been Shurff,” he relates. “O course thet don’t count no nigger rapes,” he adds, which is probably fair enough since blacks weren’t admitted to the Ranch anyway.

He goes on to tell you about the $10,000 that Edna contributed to the Hospital Building Fund, her other munificences, the economic benefits to the community, the low rate of venereal disease afforded by having county-inspected hookers on hand. As Larry Conners puts it, “He makes that whorehouse sound like a damn non-profit county recreational facility.”

Most of Big Jim’s arguments are pretty specious as well. His figures on rapes, VD, pregnancies and dope (all of which he says there are none of, excepting for niggers) are all bogus, and the $10,000 bequest about equals the annual take on the jukebox. As for the local impact, one local shopkeeper easily dismissed that: “They only got a payroll of a dozen out thar. Now how much money you figure a dozen whores’re gonna spend in this town?”

All sad but true. For all Big Jim’s efforts at rationalizing, the Ranch’s longevity was built on sentiment rather than cash, and sentiment is a poor defense against either the law or a zealous camera. Once Channel 13 weighed in against the “bawdy houses,” as they called them, there was no contest.

That doesn’t mean, however, that Zindler ever proved his vague assertions about “corruption and Organized Crime.” He never even proved his contention that the two whorehouses grossed over $3 million a year; most local Ranch-watchers think that ludicrously high and the most commonly accepted figure was about $300,000. The IRS, who never failed to collect the government’s portion, never questioned Edna’s returns.

All that Marvin had to do, really, was haul his cameras out to La Grange and put on the tube what every local farmboy for a hundred miles already knew.

Big Jim, who’d probably never before seen the business end of a TV camera, was mercilessly pinned in one of those Conners interviews. He erupted against those goddam DPS fellers who’d been pokin around last fall, and allowed as how he’d called DPS Chief Col. Wilson Speir to get them off his back. The Colonel, said Big Jim, told him to close down the Ranch until the elections were over with, so Big Jim obliged. It was the kind of interview that could make you wonder whose side he was really on.

After a week of nightly exposes, during which the Ranch kept whoring along with all flags flying, Marvin went up to Austin to interview the Governor, the Attorney General, and Col. Speir. Confronted simultaneously with prima faecie sin and TV cameras, they all professed outrage that this could be going on and promised to get to the bottom of things.

On Wednesday, the day before he was to go to Austin to answer a summons from the Governor, Big Jim capitulated. He just called Edna and told her to shut it down. Marvin promptly left for Jamaica on vacation.

Within a week of its shuttering, the Ranch is deserted, with only Lilly still hanging around to shoo off curious interlopers. Edna is hiding out with her old man in East Texas, and the girls are in Dallas, Houston, Austin, streetwalking. Big Jim is being especially suspicious of strangers, hinting bluntly to the writer from Playboy that he’s seen about all the snoopy journalists he cares to.

At Berkelbach’s Cafe in Round Top, the hangers-on discuss what to do with Marvin Zindler should he ever chance to pass through town. A petition circulates in La Grange to save the ranch, and bumperstickers make their appearance, proclaiming the same thing. Local opinion, as figured by the owner of the local radio station, breaks about even. A few local tycoons begin making plans to buy the Ranch and turn it into a restaurant, with private dining rooms in each of the bedrooms.

There is, indeed, little evidence of any sort that the ranch had ended its days. It had always existed, really, as a pleasant irrelevance, kind of a collective daydream by a rural people that believed in dreams remnant from a simpler era that had a tolerant niche for such things, along with eccentric uncles and town drunks. Like all the excess baggage from that era, realized daydreams have been burrowed under by the plow of progress. X-rated movies and celluloid sex are alright in the modern age—as is everything that is malleable into legalisms and electricity—but that additional dimension of humanity that the ranch possessed is out of scene, not immoral, just obsolete.

- More About:

- Texas History

- TM Classics

- Longreads