The collection

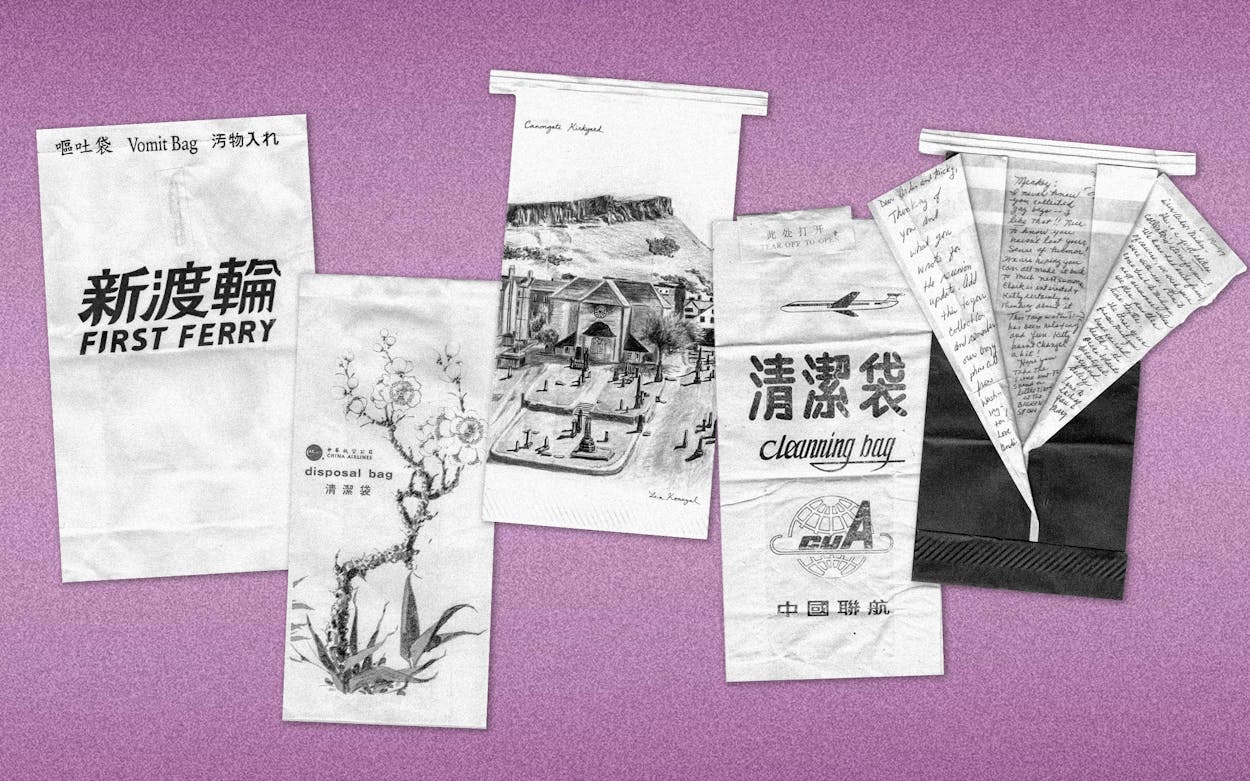

374 airsickness bags spanning 70 countries and 136 airlines, 57 of which are now defunct.

The most beautiful bag

A “disposal bag” from China Airlines featuring an illustration of an orchid. The flower is printed upside down, so that when the bag is in use (i.e., when the user is puking), the flower is right side up.

The tiniest bag

A hand-size bag from Garuda Indonesia airlines. (Writer’s note: it’s hardly large enough to contain any vomit volume I’ve ever seen.)

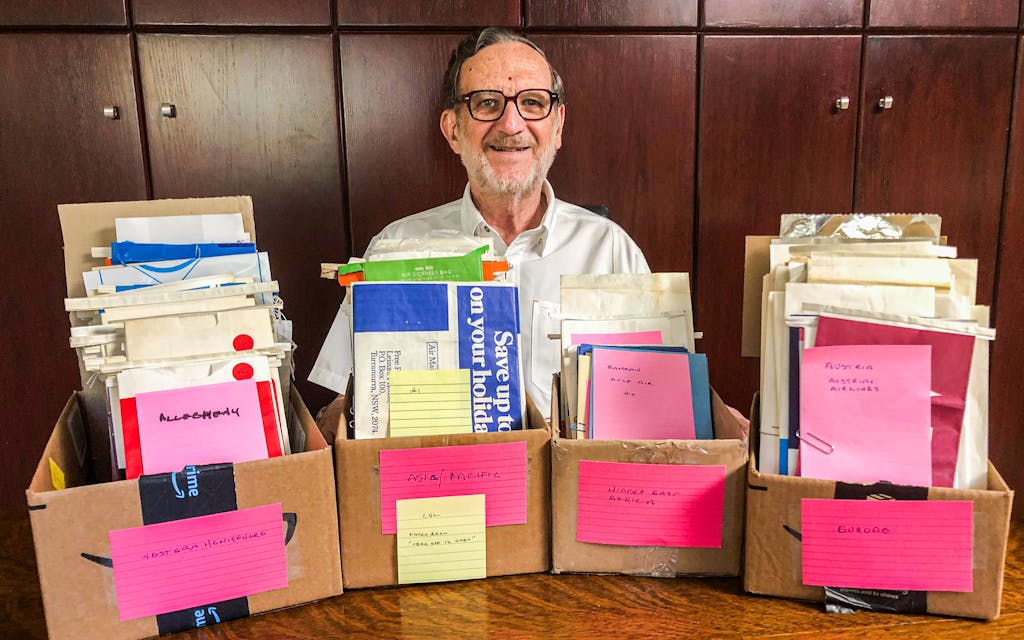

Some folks collect coins, salt and pepper shakers, or sports memorabilia; others gather countless arrowheads, buttons, or antique dolls. Eli Cox, an Austinite and retired University of Texas professor of marketing, collects airsickness bags.

The immediate question is obviously “Why?” And it’s one that he anticipates. “I’d say I did because of the absurdity . . . and I don’t think I’ve ever brought an expression of horror to anyone’s face when I told them.”

Cox’s collection began as a direct repudiation of the more traditional—and valuable—hobby of stamp collecting. It also, unsurprisingly, came out of a traveling habit. On a visit to Monaco in the seventies, Cox spied a stamp “displayed like a solitaire in Tiffany’s” in the Prince’s Palace. An active stamp collector at the time, Cox understood that, as large as his collection was, the entire thing was irrelevant compared with the stamp enshrined before him. Rather than wade through the giant community of stamp collectors as a tiny guppy, he wanted to lord over a smaller pond. He just needed an item novel enough for him to emerge as its titan. And he came up with . . . airsickness bags.

Three hundred and seventy-four impeccably organized bags later, and his entire collection still does not rival the value of that one stamp—except perhaps in sentimental value. Many of the bags—from 70 countries and 136 airlines—he acquired himself, while traveling to more than three dozen destinations with his wife over the past decades. Others were gifts from friends, family, colleagues, and students who learned of the quirky collection he’s fond of discussing. Not all of the bags are known as airsickness bags; some have more polite names printed on their paper fronts: they are disposal bags, cleaning bags, or motion sickness bags. One—from Spike & Mike’s Sick and Twisted Festival of Animation—is more upfront. It just reads “Barf Bag.” (It also features the grossest illustration of the collection; Mike pukes into Spike’s mouth, and a dog named Scotty laps it up.) Some function like postcards, with notes or signatures from the traveler who gave it to Cox.

In addition to collecting the bags, Cox has, semi-jokingly, worked to lift airsick bags in general into higher esteem, hoping to raise them to the level of reverence accorded the prince of Monaco’s stamp. From a former colleague, a professor of medieval studies, Cox copped the more official-sounding name “nausevats”: what the bags might have been called in Latin, had they existed in that era. He’s also created a jokey hieroglyphic of how a motion sickness bag might have appeared on an Egyptian pyramid and a faux timeline of when and where the bags might have appeared throughout history (e.g. the tomb of Ikhnaton, circa 1375 BC).

His humorous attempts at status-raising aside, the bags, as silly as they are, (or perhaps because they’re so silly), have become more prized as collectors’ items since Cox began pursuing them in the seventies. In 2016, at perhaps the bags’ peak value, a Dutch collector paid $500 for a now-95-year-old bag from the French airline Farman Airways. Today, on eBay, bags range from about five bucks all the way up to $18.88 for a vintage American Airlines varietal—“unused” of course.

Now that Cox is retired and downsizing, he plans to do away with the collection. He used to offer students a “collection starter kit,” in hopes that one might pick up the mantle; no one took him up on the offer. Instead, he plans to sell the bags. And as a former professor at UT-Austin’s business school, he reminds me of the boon of having invested exactly zero dollars in his collection: “Say these are worth a dollar each [and some are worth much more]. If you divide three hundred and seventy-four by zero, it’s infinite.” That’s a pretty good ROI on a vomit bag. Take that, prince of Monaco.

- More About:

- Style & Design