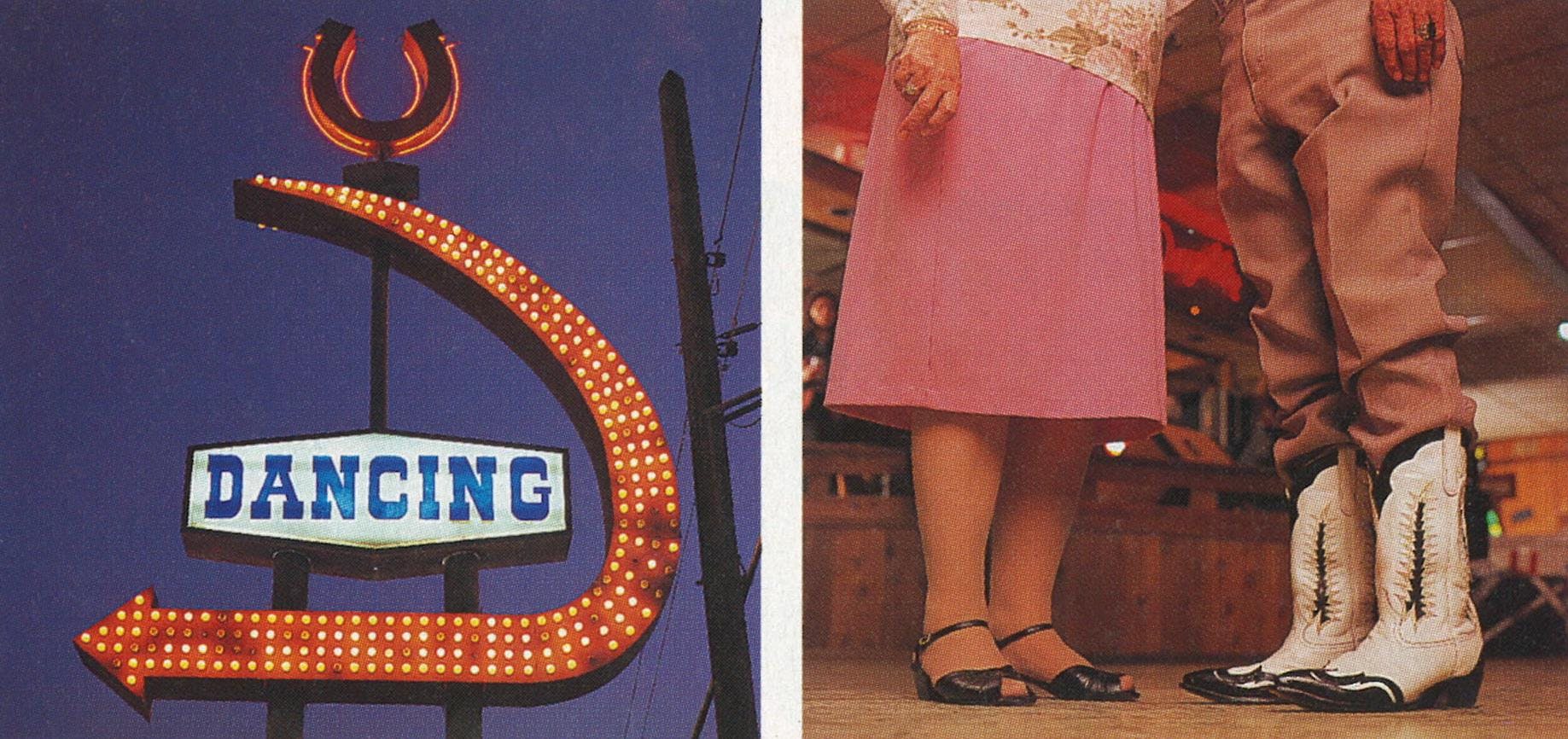

When country hunk Billy Ray Cyrus his megahit “Achy Breaky Heart” in 1992, country dancing—or at least a modern version of it—returned to vogue. Cyrus’ novelty song was released with a video that showed a line dance specifically created for the song, and—in a flashback to the Urban Cowboy craze of 1980—line-dance emporiums seemed to open everywhere overnight. Even in Texas. But here, real country dancing never went away, and many old community dance halls thrive amid the glitzy newcomers. Many go back at least three decades and a handful to the last century. Some are sparely decorated (bare walls with some benches around the dance floor); others are crammed with memorabilia. Some have full bars; others serve only beer and setups (in the classic dance halls the bar is in the front room and the dance floor is in the back). Some are urban; others are rural. Some are open nightly; others only on weekends or less often than that. But they are all halls with a history.

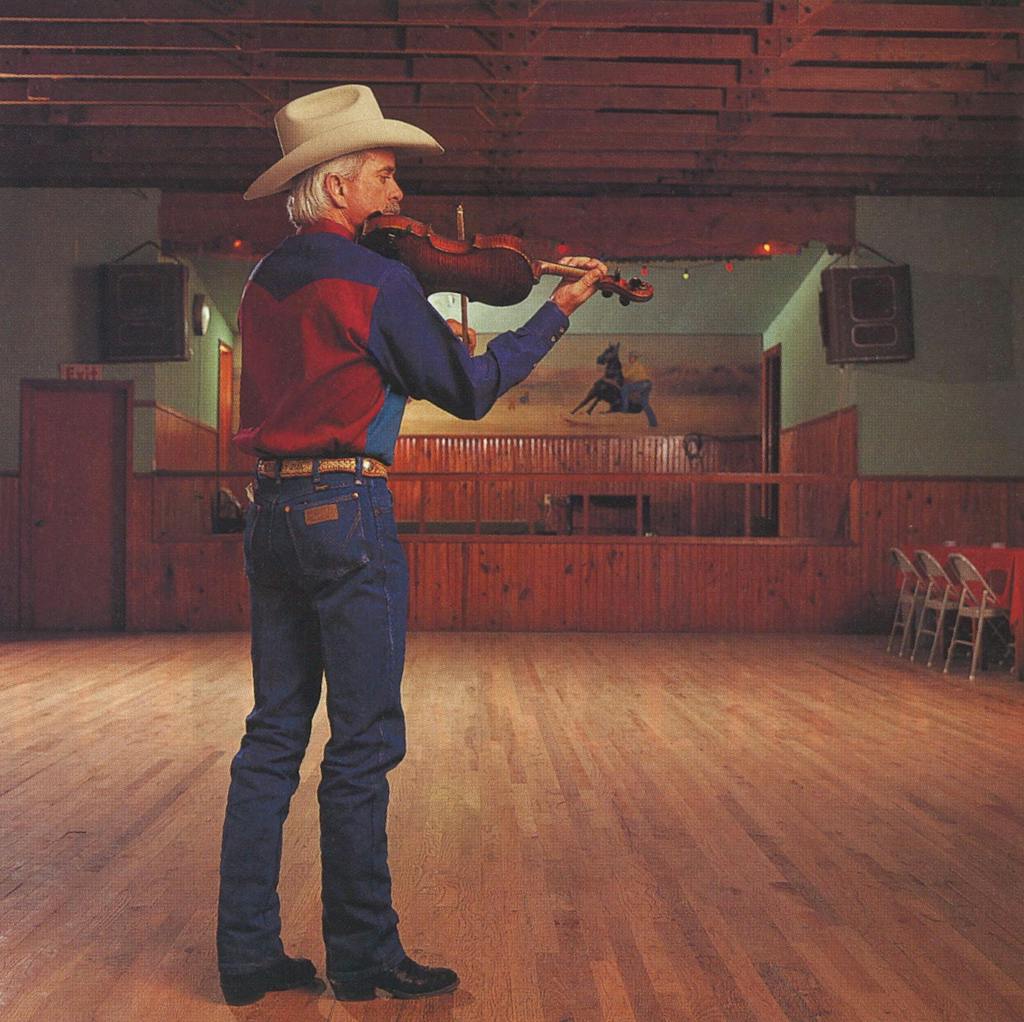

Over the years, a who’s who of country music has played in these halls, starting out with Bob Wills, the pre-war dance hall king, and then Ernest Tubb, Ray Price, and Hank Thompson. Before going to Nashville in the sixties, Willie Nelson played every dance hall in the state. When he came back, he played them all again. Jerry Jeff Walker put Luckenbach on the map, and George Strait dominated the halls in the eighties until he got too big. Today Johnny Bush rules.

But no matter who is onstage, these are the halls where line dancing isn’t done in a line, but in waltzes, two-steps, schottisches, and the traditional circle version of the cotton-eyed Joe—just as they have been for generations.

Take the Tin Hall Dancehall and Saloon in Cypress, minutes northwest of Houston. The ground floor—now a bar that also serves barbecue and snacks—was built in 1890 as a meeting place for the region’s dairy farmers. By the twenties, an upstairs was added for dances after the weekly meetings. When co-owner Fred Stockton and his two partners took over and renovated the hall in 1991, after it had been boarded up for five years, they found the faded “Floor Rules” on the wall behind some paneling. Rule number five states, “No dancing back and forth while dancing.” Today that refurbished rule is visible to the dancers, as their boots click and swish in big circles around the red-oak dance floor. Located in the middle of the woods for more than a century, Tin Hall (capacity: 2,000) is now surrounded by one of the many subdivisions that have sprung up around Cypress, and the dance hall couldn’t be more anomalous: Bordered on one side by a 27-hole golf course and on another by new houses, it sticks out like a big tin hall. (14800 Huffmeister Road, Cypress, 713-373-4554.)

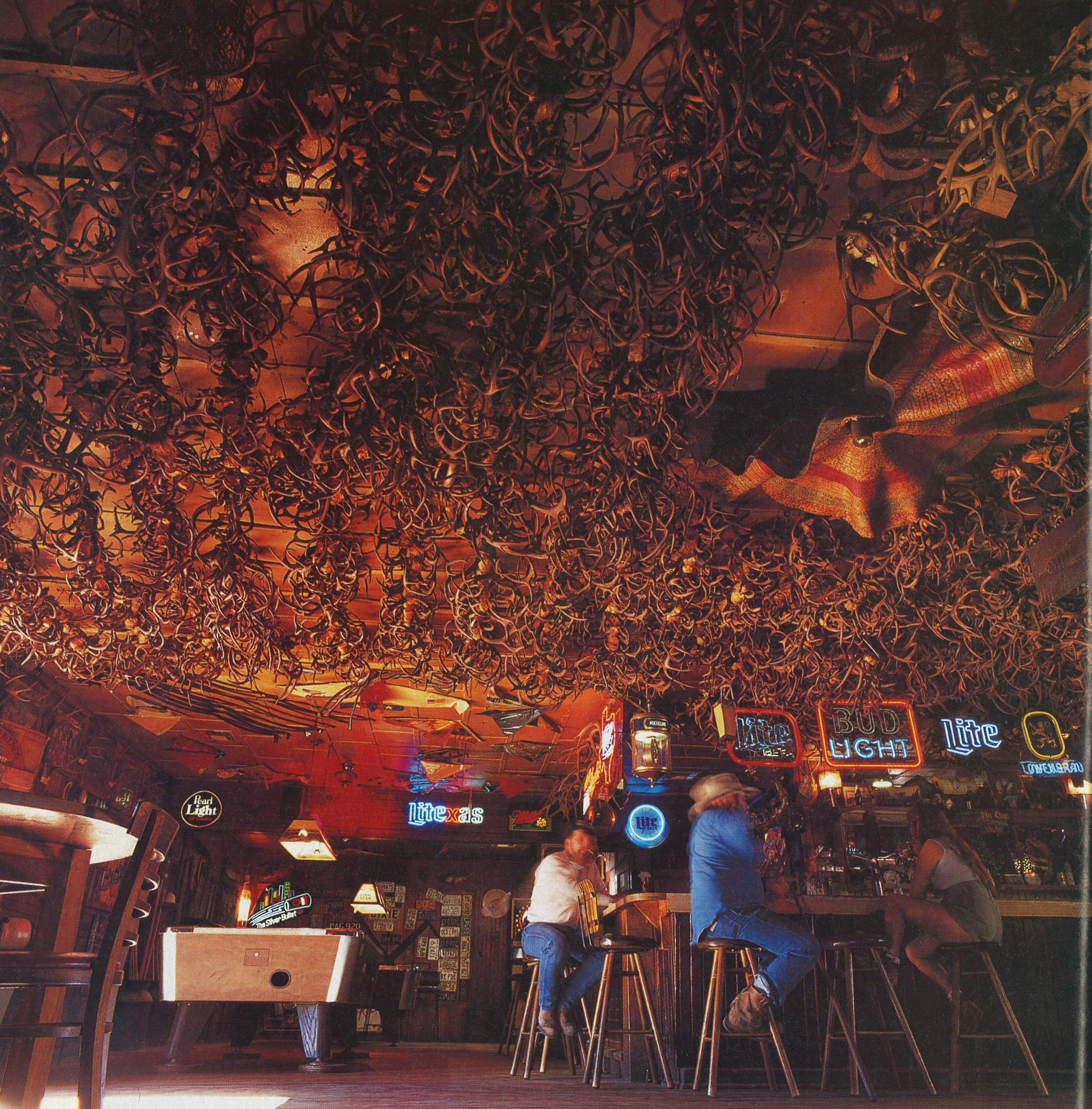

Some twenty miles north of Cypress, on the road between Magnolia and Plantersville, sits Henry’s Hideout. Henry Phillips called it “the horniest place in Texas,” and when you enter through the front door, you see thousands of antlers hanging on the walls. Phillips built the bar in 1937, adding the backroom dance hall in 1964. Before his death in 1992, he personally sold tickets at the door every weekend. “He kissed all the girls who came through,” says fifteen-year employee Diann Andersen. “He always wore a starched white shirt, and it always had barbecue sauce on it.” Henry’s sauce recipe died with him, leaving some to ponder which loss was greater. His nephew Billy Phillips now owns the Hideout (capacity: 400), and it’s still open every day of the year except Good Friday. The dance hall walls showcase Henry’s other weakness: felt tapestries. Dozens of poker-playing dogs and other animal vignettes adorn the walls, and of course, there’s a token velvet Elvis. (FM 1774, Plantersville, 713-356-8002.)

Reo Palm Isle, just outside of Longview, is the only one of the older dance halls to regularly book current stars such as David Ball (most big names go to newer, larger venues like Billy Bob’s in Fort Worth). The hall, built in 1935, has always presented touring acts, from Elvis on down, and has the autographed photos and gold records on the wall to prove it. The Reo can afford these names because it packs in a capacity crowd of 2,500 people. Reo Palm Isle draws heavily from Louisiana and East Texas, and stays open six nights a week, holding dance contests and special events to keep ’em two-stepping all week. (Intersection of Texas Highway 31 and FM 1845, Longview, 903-753-4440.)

East Texas’ fourth historic country dance hall is actually a cajun dance hall. The Rodair Club, named after an adjacent gulley in the marshes and rice fields just west of Port Arthur, was built in 1957 as a rock and roll room. It went country in the sixties, recalls the club’s owner, Joe Thibodeaux, who began leasing it for dances in 1965 before buying it in 1972. But cajun and country are kissing cousins, both heavy on waltzes and two-steps, and the Rodair (capacity: 420) has probably the highest ratio of dancers to sitters in the state. “No doubt about it. They come here to dance,” Thibodeaux says in his rolling Cajun accent. “Cajun music is the best in the world for dancing.” (FM 365, Port Arthur, 409-736-9001.)

Metroplex halls seem to have a shorter life span. In Fort Worth, once known as the dance-happy Cradle of Western Swing, the Stagecoach Ballroom (capacity: 1,000) is the city’s oldest—the owners estimate fifty years, including a previous downtown location that burned down. The Stagecoach came to its present East Side location about 25 years ago and entered its glory days in the early seventies. Those may be over, but from the Texas Rangers display in the poolroom to the string ties on the men, the hall is indisputably Cowtown. (2516 Belknap, Fort Worth, 817-831-2261.)

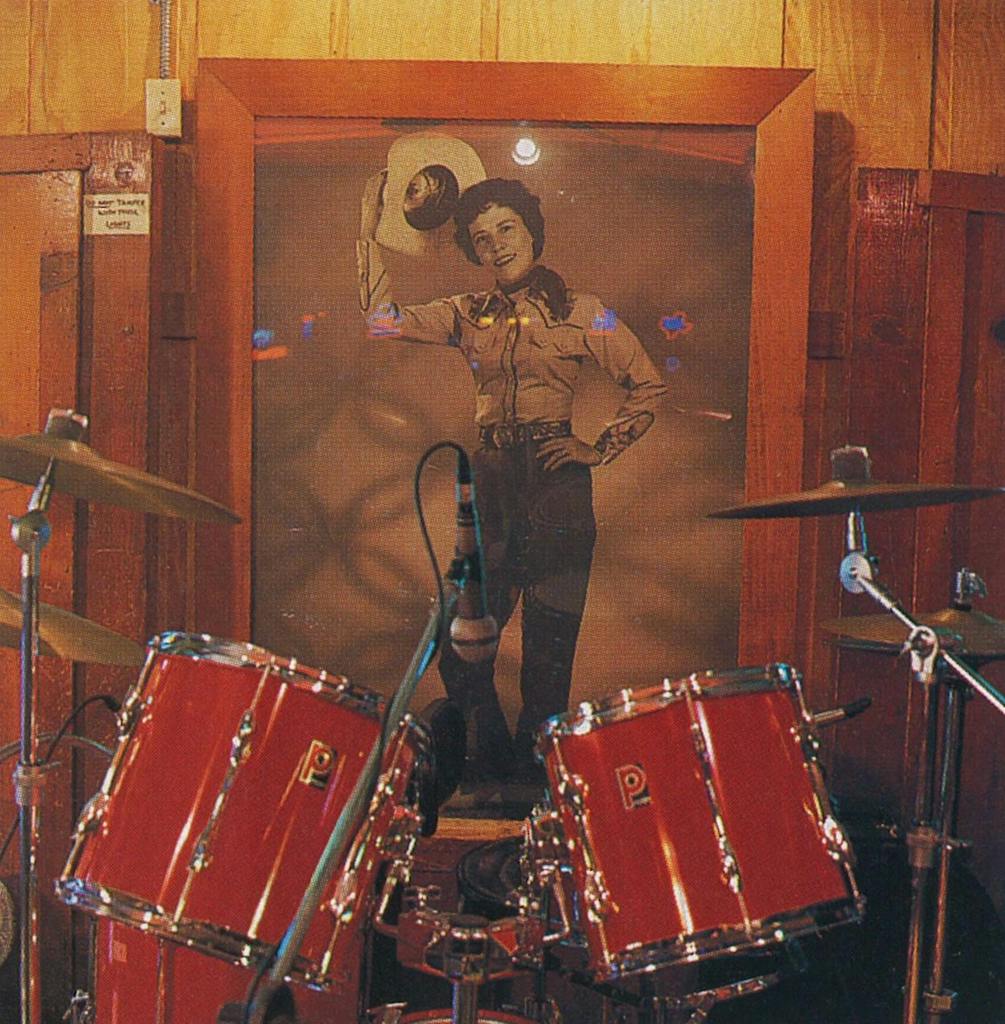

In Dallas the fabled Longhorn Ballroom (opened in 1950 as the Bob Wills Ranch House, then sold to Jack Ruby in 1952) stands dark, used on rare occasions for private functions, making the cavernous Debonair Danceland Westernplace (capacity: 1,000) the oldest in East Dallas, even though it’s only 28 years old. This dance hall has withstood all trends to remain a no-frills urban hall with a pure country house band, called the Original Debonaires. (2810 Samuell, Dallas, 214-826-5890.)

The Top Rail Ballroom, which began as a tiny beer joint on what was then the edge of Dallas, claims to be in its fifty-ninth year. “Until about ten years ago, this was a tough place in a bad area,” says manager Jerry Ferrell. After a make-over in 1993, the Top Rail looks more like a big honky-tonk than a dance hall; the building (capacity: 600) is neatly trimmed in blue and red neon with a covered wagon on top and a sign out front sporting a pair of dancing neon boots. The bands that perform there lean toward the young country sound. (2110 W. Northwest Highway, Dallas 214-556-9099.)

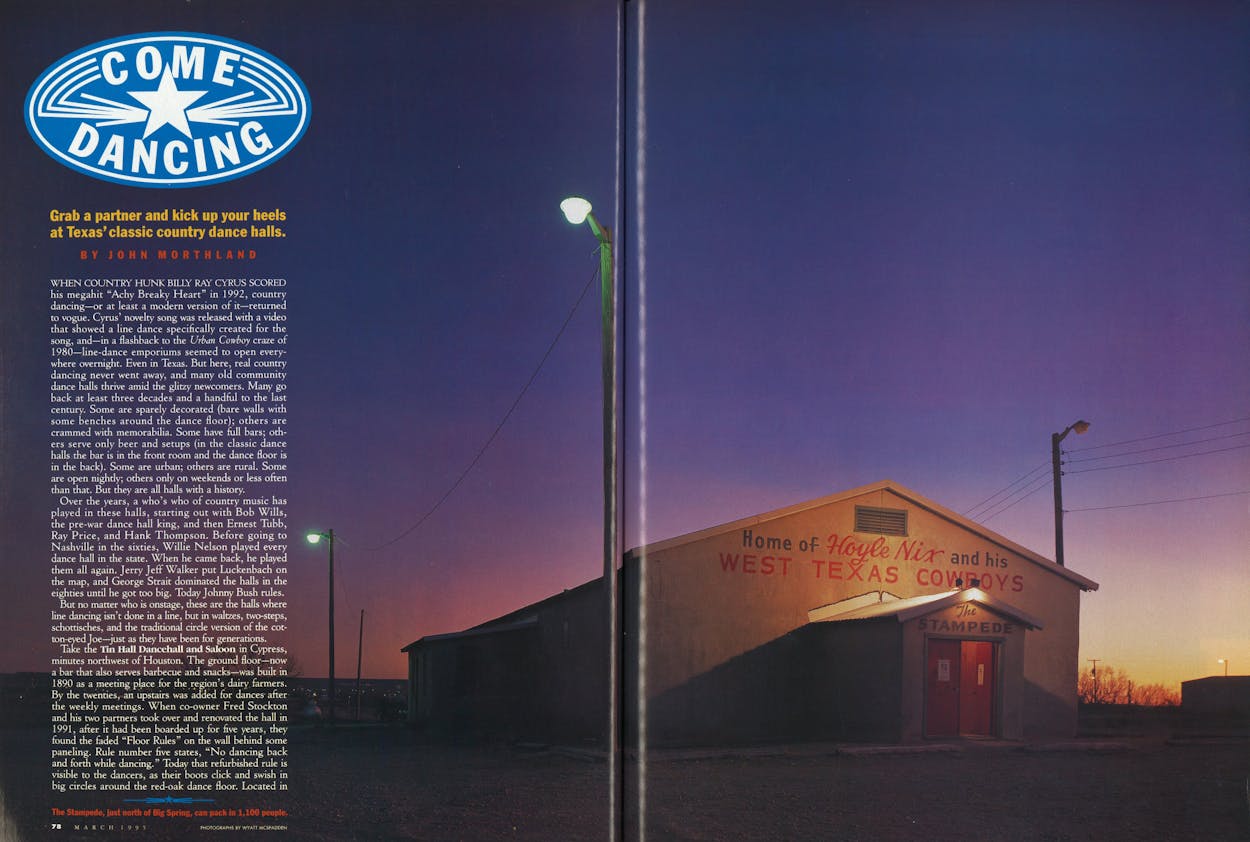

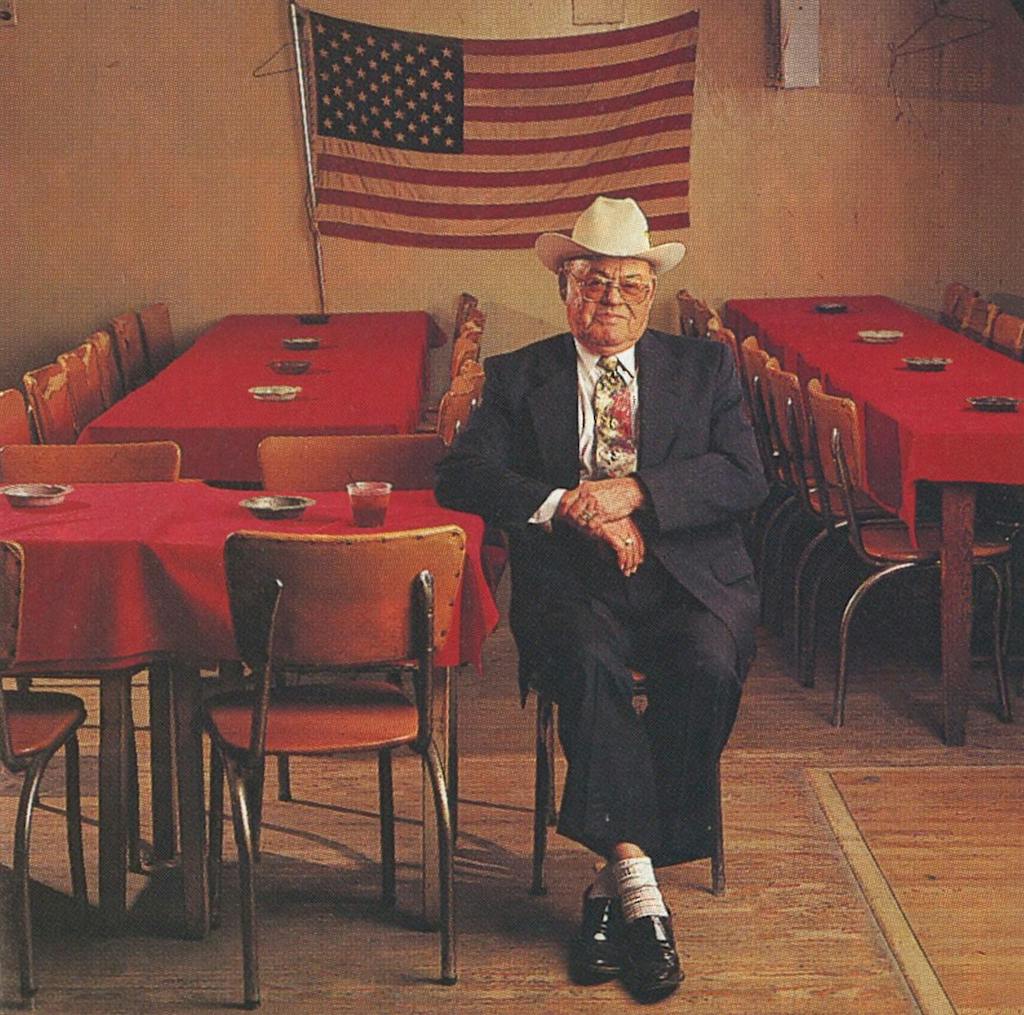

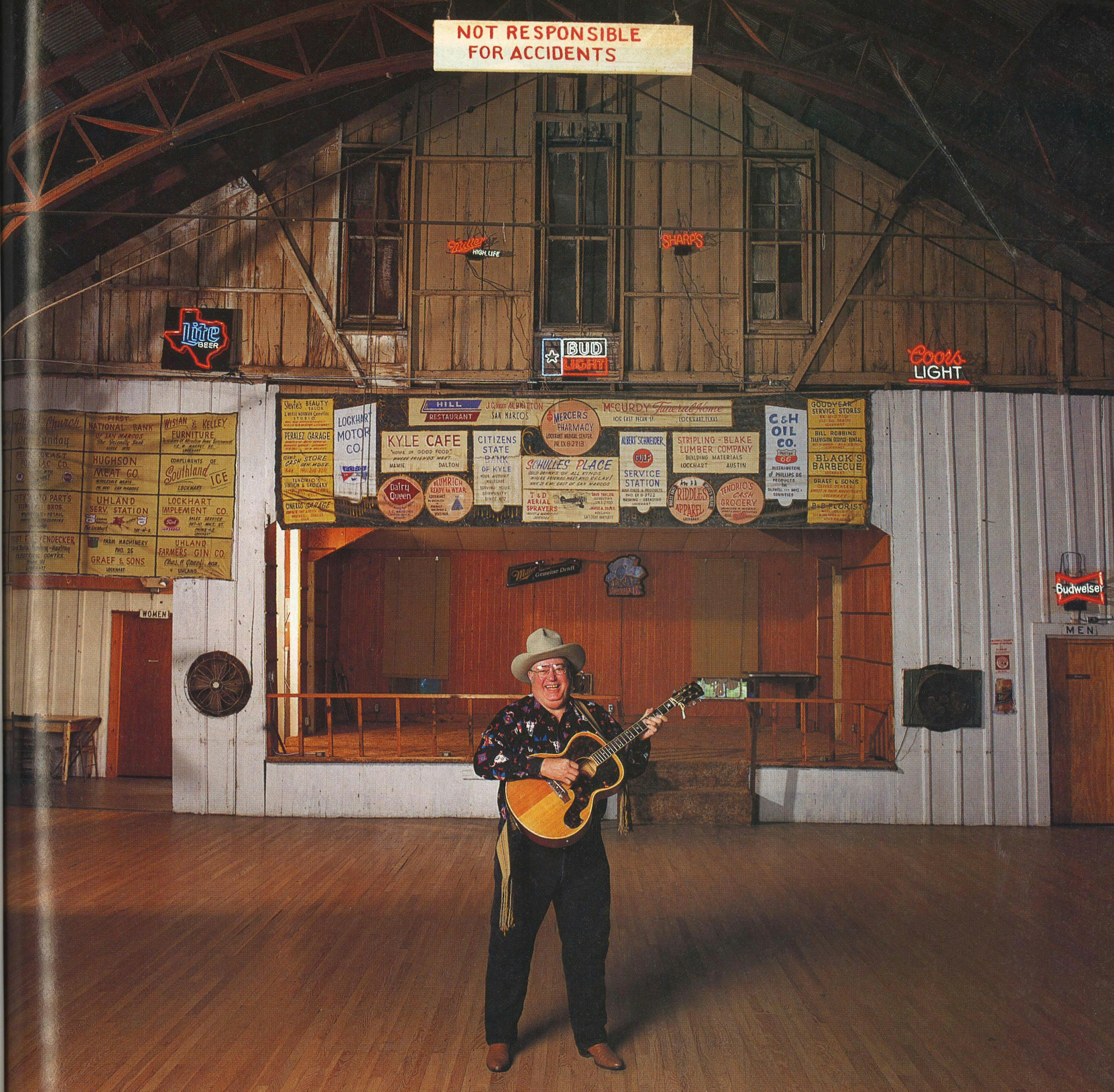

In West Texas dance halls are in short supply. Lubbock’s Cotton Club and Amarillo’s Aviatrix Ballroom are gone—and the fact is that the spread-out small towns have never supported regular dance halls. Instead, multipurpose halls are rented periodically for dances, with families coming from hours away for a Saturday night out. The Stampede, north of Big Spring, endures, but barely. Western swinger Hoyle Nix, best known for his song “Big Balls in Cowtown,” built it for himself and his West Texas Cowboys in 1954 so he wouldn’t have to travel to perform; the stage, with a small wooden fence across the front and a calf-roping mural on the back wall, is worth a visit alone. The Stampede can pack in 1,100 people, though when the tables and benches are set up around the edge of the deep, narrow room, capacity is about 500. Hoyle died in 1985, and his son Jody, a 42-year-old bandleader, who now owns the Stampede, opens only on Saturday nights when his band doesn’t have a better gig somewhere else. (Texas Highway 350, one mile north of town, Big Spring, 915-267-2060.)

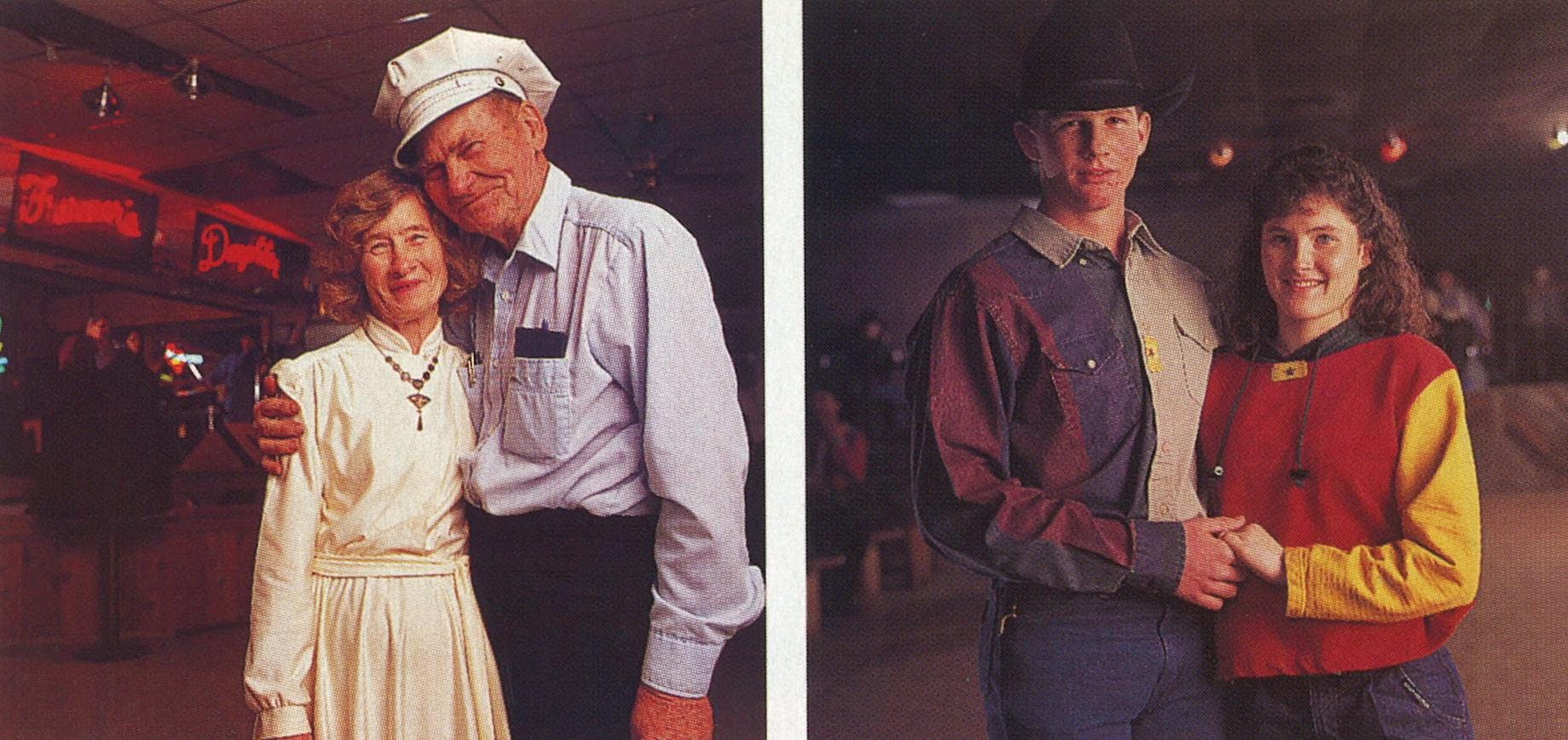

In San Antonio the Farmer’s Daughter boasts the most dazzling array of photos (including a prized autographed shot of Jimmie Rodgers) and memorabilia in the state. It opened in 1961 as the first East Side club, and so many of its original customers have stayed loyal that the Farmer’s Daughter (capacity: 600) has a reputation of catering to oldsters. Though he’s trying to attract more families, owner Ivan Romjue believes, “This is the truest dance crowd: As soon as the band begins to play, the floor fills up.” It’s an early Sunday afternoon as he speaks—dancing begins at two on Sundays, making it easier for the elderly—and sure enough, as Neala Gayle and the Heartbeat of Texas break into Ray Price’s “Crazy Arms,” the floor gets busy. (542 N. W. W. White, San Antonio, 210-333-7391.)

John T. Floore Country Store was launched in Helotes in 1942 by John T. Floore, the fast-talking ladies’ man who had previously been a booker and promoter of the Majestic Theatre in nearby San Antonio. At that time it really was a store (and notary public, post office, bus stop, voting booth, sausage stand, insurance office, and real estate office), but in 1946 Floore built an adjoining dance hall that has outlasted the store. The walls bear almost as many pictures of Floore, usually with a celebrity or sexpot, as of the musicians who’ve played the three- hundred-capacity dance hall. For bigger shows, the outdoor patio with stage and dance floor accommodates about a thousand. Willie Nelson, a good friend of Floore’s, played here often, especially after coming back from Nashville in the early seventies. Willie immortalized Floore in the song “Shotgun Willie”: “Now John T. Floore was workin’ for the Ku Klux Klan/Six foot five, John T. was a hell of a man/Made a lot of money selling sheets on the family plan. ” The music ranges from the country-flavored rock of Augie Meyers to the rock-flavored country of Gary P. Nunn. (Nine miles north of San Antonio’s Loop 410 on Texas Highway 16, Helotes, 210-695-8827.)

Austin’s Broken Spoke, one of the most famous venues in the state, turned thirty last year. A favorite of tourists and locals, the Spoke (capacity: 450) offers a variety of dance bands and a country music museum with enough sense of humor to exhibit a half-smoked Bob Wills cigar (3201 S. Lamar Boulevard, Austin, 512-442-6189). But it’s still in its infancy compared with Dessau Hall, just north of Austin, which was built as a community center in 1876. Known for the pecan tree growing through the floor and out the roof, the dance hall won its reputation in the late twenties. Big bands like Glenn Miller’s and Tommy Dorsey’s played there, as well as country legends from Bob Wills to Hank Williams. After it burned in 1968, a much larger hall (capacity: 750) was built, and it can be described in one word: “red”—as in red tablecloths, red hanging lamps, red flocked wallpaper, and red carpet. Beginning next month, the hall officially changes its name to Dessau Dance Hall and Saloon and will have live music seven nights a week. (13422 Dessau Road, Austin, 512-251-4421.)

After several years of darkness, the Coupland Dance Hall and Tavern (capacity: 700) was revived two years ago. The original dance hall was opened in 1936 (as La Casa Grande Ballroom) in a building that was built in 1911. When Austinites Tim and Barbara Worthy took it over in 1993, they renovated the hall, adding a dance floor and funky Texas antiques. The chairs at the tables surrounding the dance floor are of the no-two-alike variety, and white Christmas lights snake around the beams (colored lights decorate the outside). The bookings include veterans on the way down (Hank Thompson, Gene Watson), youngsters on the way up (Crossover, featuring Ken Ryan, a deep-voiced singer who is about due for a recording contract), old reliables (Johnny Gimble, Johnny Bush), and some surprises (Brian Black, Clint’s older brother). (115 Hoxie, Coupland, 512-856-2226.)

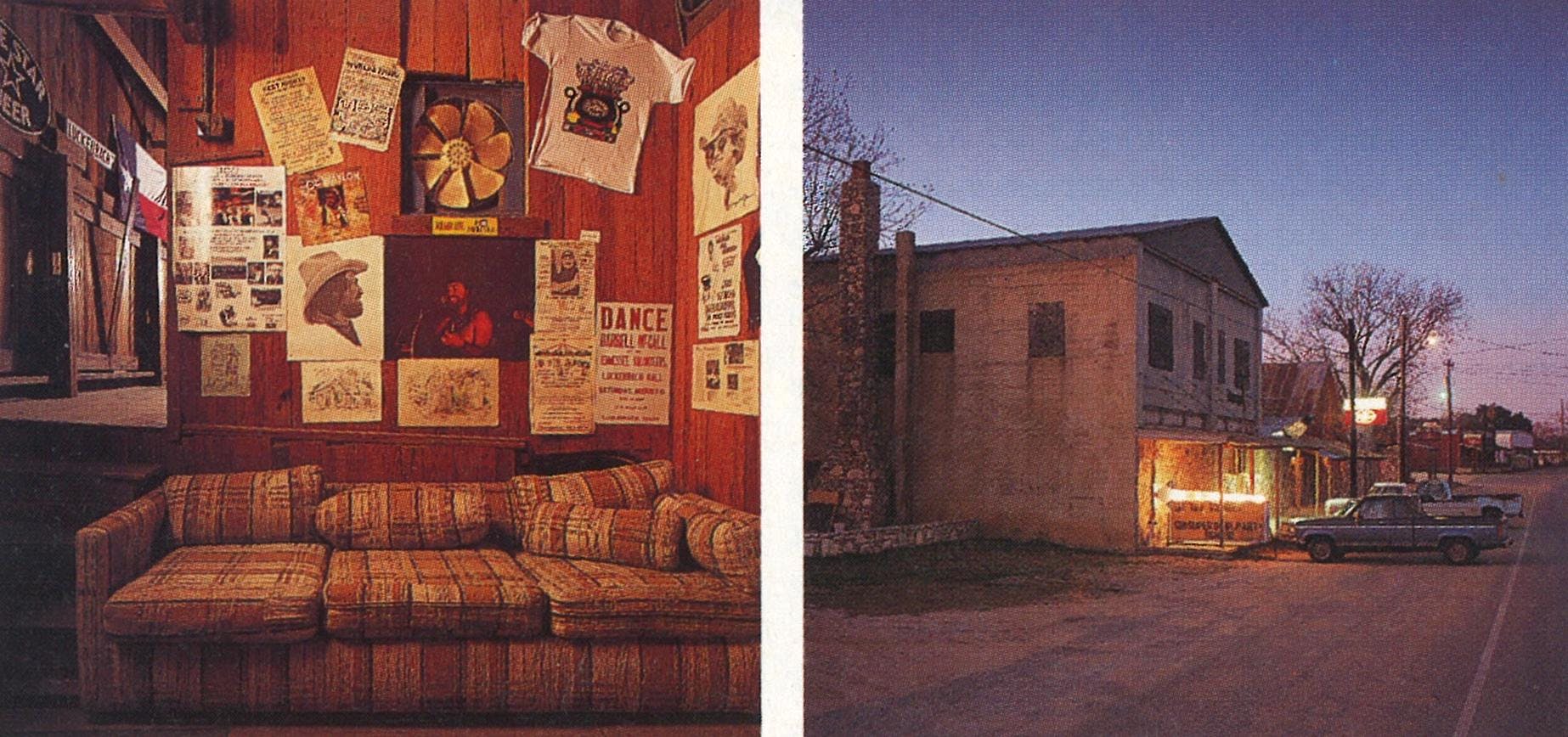

In Hill Country towns couples dance polkas and the put-your-little- foot as well as schottisches and two-steps. The band might sing songs from the Czech or German old country. But two of Central Texas’ oldest halls are now more in the musical spirit of Austin’s seventies landmark, the Armadillo World Headquarters. Luckenbach Hall, made famous when Austin songwriter Jerry Jeff Walker recorded his breakthrough ¡Viva Terlingua! album there in 1973, goes back to 1880 and hasn’t changed much. The weather-worn cedar hall has creaky wooden windows that are pulled out and propped open to let in light and air. A lone beer sign—it’s not even neon—hangs from an overhead beam, the only decoration besides the Lone Star flag and a “Luckenbach Population 3” sign behind the stage. Once the site of regular dances, the 350-capacity hall usually opens once or twice a month; when Austin icons such as Walker, Robert Earl Keen, and Gary P. Nunn play, it’s too packed to dance. (Luckenbach, 210-997-3224.)

Luckenbach’s counterpart is Gruene Hall, built in 1878, which bills itself as the state’s oldest continuously running dance hall. The dance hall looks much like Luckenbach Hall. For most of the year, Gruene (capacity: 500) has live music on the weekends, with bookings broad enough to have included primal rocker Bo Diddley, country-folk eclectic Lyle Lovett, the late bluesman Albert Collins, and contemporary rock singer-songwriter John Hiatt. In the summer, when there is live music six nights a week, the tourists want country dance music. As the anonymous lead singer of the Ace in the Hole Band, George Strait sang there Saturday nights for six years before achieving stardom. (1281 Gruene Road, New Braunfels, 210-606-1281.)

The Fischer Dance Hall was built by a one-eyed carpenter in 1875 and is now part of a complex that includes an outdoor pavilion and nine-pin bowling alley. The old wooden dance hall is as plain as can be. Scenes from the 1980 Willie Nelson movie, Honeysuckle Rose, were filmed there, but these days the hall is used mostly for covered-dish suppers and wedding receptions. The annual Christmas Dance is the social event of the year for the surrounding area, and it is open to the public. The hall can also be rented for parties. (FM 484, Fischer, 210- 935-9222.) Nearby, Twin Sisters Hall (capacity: 500), in Twin Sisters, which claims to go back to 1869, is open for dances the first Saturday of every month. The original painted advertisements from the thirties are on the stage curtain, and handmade wooden chairs and tables surround the dance floor. The bar—which sells $1.25 beer and 75-cent soda—is smooth from wear, but the dance floor is even slicker; for some kids, the high point of the evening comes during intermissions, when they can slip and slide across the floor. (Seven miles south of Blanco on U.S. 281, Twin Sisters, 210-833-4808.)

The best-known outdoor dance hall in Texas is Crider’s Rodeo Arena and Dance Hall near Hunt. The dance area consists of a large cement slab with an ailing oak tree growing through it. No walls, no roof, but family member Elaine Crider Hurt can’t remember the last time it rained during a dance. For years Crider’s was a Saturday night tradition, but a 1993 fire destroyed the snack bar and damaged the tree (see “The Last Dance,” October 1993). The Crider family isn’t certain when the hall will reopen, but Hurt is optimistic it will be running again this summer. With the dance floor and the adjacent rodeo arena, the capacity is around five hundred. (Four miles west of Hunt on Texas Highway 39, 210-238-4874.)

The Quihi Gun Club is the most off- the-beaten-path dance hall in Texas. Quihi is an unincorporated area about ten miles west of Castroville and is reached from there by taking County Road 4516, a barely paved road (bear left at the fork) that becomes gravel toward the end. The only other way to Quihi is via FM 2676 out of Riomedina. However you get there, the trip is worth it. The Quihi Gun Club, originally built in 1890, is a long V-crimp tin building, which sits six feet off the ground on cedar posts (a measure taken after a flood warped the dance floor in the forties). The inside is just as plain—a couple of beer signs, some tables, and a few posters. There is room for five hundred, and though it hasn’t been filled since the fifties, folks still come from all over to dance on Saturday nights. (Telephone number is unlisted.)

Club 21 in Uhland and London Dance Hall in London, classic small-town dance halls at opposite ends of the Hill Country, also remain resolutely country. On an early Friday evening last summer, young men in cowboy hats milled in front of Club 21 (capacity: 400), even though the Southernairs wouldn’t be playing for an hour. Inside, a few people quietly ate or drank in the bar, which was built in the mid-1890’s. The dance hall was added in 1912, and an adjoining nine-pin bowling alley was added in the early thirties.

“I’ve had people eighty years old come in and tell me they met their wives here,” current manager William Ilse said. “Most people don’t know where Uhland is, but they know where Club 21 is.” When the Southernairs began playing, a girl of about eight steered her grimacing brother (maybe half her age) around the floor. They were soon joined by older couples, and then the band broke into the traditional “Chicken Dance,” and everyone began flapping. Now that, like the man said, is country. (Old Spanish Trail, Uhland, 512-398-2901.)

So was the Saturday scene at the London Dance Hall, as owner Billy Ivy and her daughter, Sheri, alternated between taking money and stapling tickets to shirt collars. London is in the middle of a triangle formed by Mason, Junction, and Menard, and the hall, which holds about eight hundred, draws heavily from all three. It’s been patched together over time from four different buildings: The core building is about a hundred years old, Billy Ivy says, and the dance hall itself dates back to the late twenties. When Ivy took over eight years ago, there wasn’t even a men’s room. An exit door near the stage read “Men” and opened up to the great outdoors, where gentlemen joined others around an ancient tree to relieve themselves. When Ivy added a real men’s room, she painted an oak tree on the wall above the urinal.

Inside, the dance hall was loud, friendly, and animated all at once—the way Saturday night is meant to be. Younger dancers stood in groups, flirting and sizing up their prospects. As the Fredericksburg band Southern Image broke into its countrified version of the Rolling Stones’ “Honky Tonk Women,” the kids let out a collective whoop. When that ended, the cotton-eyed Joe began, and they happily turned the floor over to their parents. The band followed with a medley of Roy Orbison ballads and the kids were back out there dancing real, real close. “My family goes back to the 1850’s in this town,” Billy Ivy said. “We all learned to dance right here.” Was there ever anything else to do on a Saturday night? “No, this was it,” she answered. “It still is.” (U.S. 377, London, 915-475-2921.)

- More About:

- Music

- Farmers

- Country Music