This story is from Texas Monthly’s archives. We have left the text as it was originally published to maintain a clear historical record. Read more here about our archive digitization project.

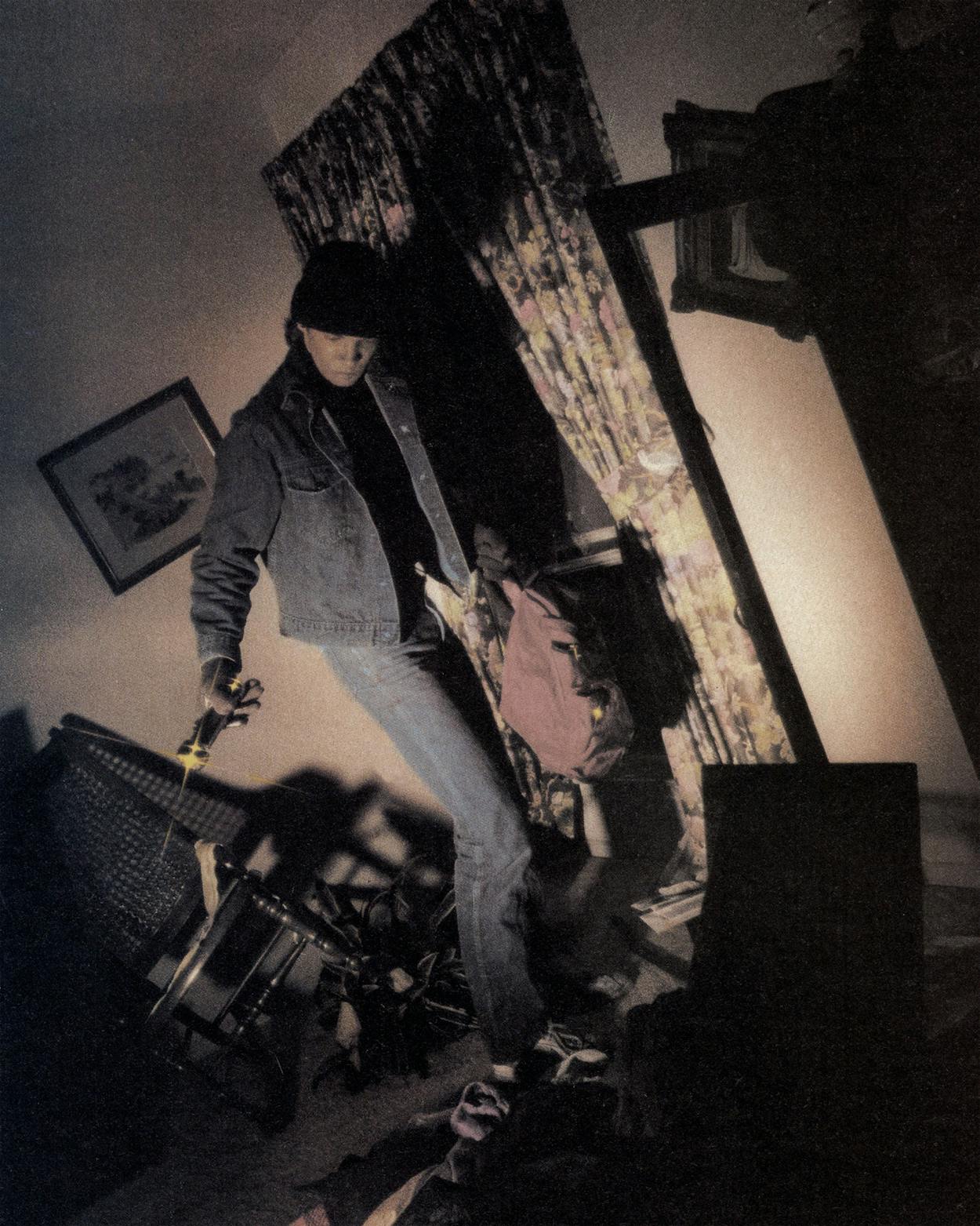

I surveyed the ugly aftermath of the break-in, mentally calculated the loss in property, sighed and shook my head in unison with the investigating police officer, and then I did what all good contemporary burglary victims do—I felt lucky. Most of my wife’s jewelry was gone, my bedroom window had been mangled beyond recognition by a crowbar, my entire home stank of the especial odor of violation; yet all I could think about was what could have happened. “Look at it this way,” I told my wife, who didn’t look as if she felt very lucky at all. “He could have found the silver. He could have come in when you were here alone. He could have torn the place up just for kicks. All things considered, I guess we were pretty damned lucky.”

For some days after the burglary, I worried that this reaction was singularly warped. Lucky? Weren’t burglarized homeowners normally enraged, depressed, frustrated, or some combination of the three? But over the six months since the break-in, I’ve discovered in exchanging burglary tales with friends and colleagues that I am hardly alone in falling prey to what I call the Lucky Victim Syndrome. Indeed, it seems to be a pervasive trend in Dallas, a city that is becoming aware that its burglary rate is out of control. “I was just damned lucky,” said one acquaintance matter-of-factly, “that I’d scheduled some of the jewelry with the insurance company a week before my number came up.”

Even the police, of all people, seem to have warmed up to the notion. After waiting a more-than-polite two months to hear something from them, I finally called the Northeast Division to check with the investigator who’d purportedly been assigned my case. She was a pleasant, sympathetic young woman, but she said nothing to persuade me I wasn’t right in feeling lucky. There were no leads on the burglar or the property, and it was doubtful that there would be. Just like 75 per cent of the other burglary cases in Dallas last year, mine was probably headed straight for the “uncleared” shelf. “I get a hundred of these to deal with each month,” she said tiredly. “Most of them are like this. You had insurance, right? That’s lucky.”

What’s going on here?

The truth is that burglary victims like me have come to feel lucky because there is really no other choice. Feeling lucky is our last defense against a crime that seems to have completely overwhelmed law enforcement and made a mockery of the courts. Dallas isn’t being singled out as the exception to the rule here; rather it seems to be a paradigm of a national trend.

Law enforcement has never been especially good at catching crooks, and so its basic response to ever-rising crime rates in recent years has been to narrow, slowly but surely, the definition of what constitutes a crime. Some of this redefinition has taken the form of virtual decriminalization of certain crimes—juvenile crime, some narcotics and so-called morals violations, selected traffic crimes. But the rest of it has been a kind of informal, de facto decriminalization. It’s not likely to be discussed in a state legislature or even whispered by a law enforcement official, but in effect, burglary, the most common felony, is rapidly becoming at best a kind of “victimless” crime, at worst no crime at all.

Look at the statistics:

•There were 30,000 burglaries in Dallas last year, an increase of 12 per cent since 1979. Only 25 per cent of them will be followed by an arrest or by recovery of the stolen property. And that doesn’t account for unreported break-ins, which could conceivably double the 30,000 figure.

•Those 30,000 burglaries will account for some $40 million in pilfered property; the police will recover only one tenth of it.

•Of the suspects arrested, half or more will be juveniles and will quickly disappear into that judicial black hole known as the Texas family court; most of them will be released in the custody of their parents. Of the adults, the first offenders will likely be handed five- and ten-year probated sentences and returned to the streets. Repeat offenders will be dealt with primarily by way of plea bargaining, resulting in five- to ten-year prison terms. Many will be eligible for parole in fifteen months to two years.

•According to a repeat offender study conducted by the Dallas Police Department (OPD) in 1973, at least 69 per cent of those arrested last year will encounter the system again—probably by being arrested for burglary.

• Including estimates of unreported break-ins, only one in fifty burglaries in Dallas last year will result in a prison sentence.

To be sure, there are understandable reasons for that last sobering fact. The sheer bulk of crime, especially in a rapidly growing city like Dallas, is overwhelming: 30,000 burglaries in a city the size of Dallas doesn’t mean much until you realize that they are being investigated by a paltry 109 officers, most of whom have other duties. That’s 275 cases per investigator per year—a little more than 1 per working day. Even if a good number of those cases require minimal paperwork, it’s not difficult to see how a burglary investigator could quickly get to the point of doing less and less about more and more.

And an unwieldy boom town like Dallas presents further problems. Between 1975 and 1980, for example, the geographical area to be covered by the DPD increased 25 per cent; the number of residents to be protected increased about 3 per cent; citizens’ calls to the department accordingly increased 31 per cent; beats to be patrolled increased 42 per cent. During the same period, police manpower rose only about 3 per cent. Add to that the sticky matter of police priorities—Dallas also has one of the highest reported per capita rape rates in the nation and rapidly rising murder and robbery rates.

All this explains part of the problem, but many cops will tell you that burglary has never been an easy crime to solve. By its nature it is private and clandestine; the odds of victim confrontation are low, as are the odds of there being any other witnesses to the crime. And because burglars are generally wary criminals, they are relatively careful not to leave telltale traces that could be of help to investigating officers.

Moreover, the notion that burglary can be effectively investigated, as law enforcement officials like to put it, “through the back door”—meaning by tracking stolen goods back from large fencing operations to the actual burglars—is largely a myth. Thirty or forty years ago, in the days of the “professional” or “specialized” criminal, this was probably true: burglars were burglars, fences were fences. An investigating officer could run his traps on the street and stand a chance of getting a tip on which character pulled a particular job. But increased narcotics use, recurring economic recessions, and a juvenile system that refuses to believe that kids can be hardened criminals have brought a lot of new faces into the burglary business.

My burglar, for example, was obviously not a pro; he knew little about what he wanted, even less about how to get in and get it, and probably wouldn’t know a fence if he saw one. Chances are that he was some kid—maybe from my neighborhood—or an addict supporting a habit. He probably unloaded the booty that very day to a friend or someone he ran into in a bar; or he might have just kept it himself. In any event, he’s not likely to sell the property to a source known to the police. As a result, my property—the only real evidence of the crime—virtually disappeared, eliminating yet another possible avenue of investigation.

The relentless occurrence of burglary, coupled with the difficulties of investigating it after the fact, have forced the police to pick and choose which burglary cases even to bother with. As Dallas assistant chief Billy Prince puts it, “Where property loss is low, where there was no danger to the victim, where we have no witnesses or other leads, we just have to suspend the case immediately. That doesn’t mean that it’s really dropped. But you have to apply possibilities and probabilities to burglary cases. It’s a form of quality control.”

Officials like Chief Prince defend the seemingly low number of investigators assigned to the city’s most widespread felony, but they can’t defend the fact that even as my home was being burglarized that day, there were probably three officers on the street in front of my downtown office writing parking tickets. Manpower is short, but why does a city in the midst of an unprecedented outbreak of serious felonies have half again as many officers assigned to traffic as to burglary investigation? Moreover, no fewer than three of Dallas’s finest spent a total of two hours at my home after the crime. Wouldn’t those six man-hours have been better invested in preventive patrol in my neighborhood before the fact?

Charles Silberman, a New York–based criminologist and author of the definitive Criminal Violence, Criminal Justice, says this situation is primarily the result of the police force’s perception of the public’s law enforcement priorities. “We probably have our priorities screwed up,” he says. “But this has to do with the pressure the public puts on the police—or the pressure the police perceive from the public. No police chief gets fired for crime increases. They get fired for ticketing the wrong car and letting traffic get out of hand.” Since the arrival of the crime-is-a-fact-of-life era, the appearance of law and order has been at least as important as the actual maintaining of it. And because most decent, law-abiding citizens still observe or come into contact with their police department only through the traffic patrol, police departments understandably—if indefensibly—continue to place a high manpower priority on simple speeding and illegal parking. (A less charitable explanation is that traffic tickets are a primary source of income for any city government, so it behooves the politically astute police chief to keep checking those parking meters.)

To make matters worse, few crime victims are dealt with more skeptically by the police than the burglary victim. There is an implicit assumption that it’s all your fault to begin with, and there is often a suspicion that the victim is jacking up his losses with fabricated property. Even for those few fortunate victims whose burglars are arrested or whose property is recovered, the ensuing ordeal may or may not be worth it.

Most burglary suspects are subsequently linked to several other similar crimes, often as many as fifteen or twenty. But because of the difficulties of developing evidence in every case, not to mention the problem of overcrowded court dockets, investigators frequently choose to drop all but two or three of the cases in return for information from the suspect on other burglars and burglaries. This procedure is justifiable, but the result, as often as not, is that some victims have their burglaries technically cleared not only without seeing justice done but without ever even knowing about it. David Clark, a veteran Dallas burglary investigator, recently explained this odd practice: “We just don’t have the time. We can’t reach all of them. People move. Some of these burglaries are pretty old.”

Even if the victim finds out one way or another that the burglar has been identified—but won’t necessarily go to trial on his case—investigators frequently refuse to tell him much about the perpetrator. “I might tell a victim his name, but that’s all I would tell,” said Clark. “I might be infringing on his rights. Besides, I don’t think the burglary victim would kill the guy, but he might and I wouldn’t want that on my conscience.”

If his property is recovered the victim may be in for another hassle. Much property turns up in local pawnshops and is traced through the DPD’s automated Property Recovery and Identification System, a program that matches pawn tickets against stolen property lists on a periodic basis. But because most pawnshop owners continue to maintain the fiction that they don’t know if any of the property they buy is stolen, and because most victims have neglected to keep serial numbers or other irrefutable evidence of ownership, a victim can’t just walk in, claim the property, and take it back. He must either prove it’s his or—get this—buy it back from the pawnbroker. This strange state of affairs is endorsed by the police. “When I get some recovered property,” said Clark, “I’ll call the guy and tell him it’s at X pawnshop and that the pawnbroker bought it for thirty dollars and that if he wants it right then, the easiest thing to do is to go out there and give the guy thirty dollars. Otherwise, we’ll have a hearing before a magistrate to establish ownership. It’s up to the owner; we don’t want to get in the middle of it.”

If the police unwittingly make the burglary victim feel like a criminal, they also tend to encourage burglars to recidivate by doling out reduced charges in exchange for information. This practice is rooted in law enforcement’s longtime fixation about the value of criminal informants. And there’s little question that informants are valuable: criminals are their own tightly knit subculture; they talk to one another and only infrequently come into contact with the law-abiding public on the streets. Invading their realm through loyal informants has produced many a narcotics or theft ring bust and conceivably can serve as an effective deterrent to certain types of crimes (if criminals sense that the Man is anywhere near, they’ll move on, change criminal specialties, or at least take a brief vacation).

But there’s a certain if-you-can’t-beat-’em-join-’em element to this business that is troubling. The question is: when is enough enough? When do the police get to the point of actually creating crime—through lenient treatment of arrested suspects—in order to fight crime—through subsequently obtained tips? Investigators like Clark are apparently convinced that no amount of inside poop from a suspect is too much. “If I tell a guy I’m going to file in all eight cases,” he says, “he’s not going to tell me anything. But if I tell him I’ll drop some if he’ll talk, then I have a better chance of getting back property for victims in some other cases. You have to play ball with them.” True, but at what point do the three or five or ten additional cleared cases obtained from an informant begin to be offset by the recidivism of those burglars who know they can be back on the streets in a few months if they “play ball”? The question seems to be an especially appropriate one for law enforcement to ask itself, since no study I’m aware of has provided a statistical rationale for the widely held belief that informants are worth the price we pay.

Law enforcement can defend itself for only so long before it starts pointing fingers too. The primary target is the courts, which officers will tell you privately are more of a hindrance than a help in seeing that the few burglars caught are properly punished. The chief complaint here is that judges routinely set bonds too low on arrested burglars. Burglars are considered low-risk bonding prospects; despite their well-known tendency to recidivate, they are not considered a true danger to public safety. “The law provides the requirement that bond setting not be used as a punishment tool but as a means of making certain the defendant shows up for trial,” says Dallas district judge John Ovard. “Burglary is just not a high-risk bond situation. They do show up for court.” A second, less acceptable explanation, however, is that many judges set bond on burglars without checking their records. A low bond for a first offender is probably reasonable; no sense in further crowding the jail with a criminal who hasn’t yet proved a tendency to recidivate. A repeat offender is a different matter. There is a good chance he will continue to recidivate, and while he may not constitute a danger in the eyes of the courts, he certainly will in the eyes of his next victim.

The judiciary’s haphazard approach to handling burglars continues at the sentencing stage. Of 165 randomly selected cases over a three-month period late last year, 157 were plea bargained and 8 were tried before a jury. In the plea-bargained cases nearly half received probation—meaning they returned to the streets with at least the opportunity to put their crowbars to work again. The other half, who received penitentiary time, were sentenced to an average of 11 years. Many judges would argue that that’s a sufficiently high average sentence, but a measure of how out of tune the courts are with public sentiment about burglars may be found in the average sentence imposed by juries in the 8 cases that went to trial—72 years.

And none of these statistics include our juvenile courts, which, according to the best available evidence, may handle as many as half of the burglars in the city during any given year. The juvenile system has been looking for its nadir for some time, and its contribution to the current burglary epidemic may well be it. A couple of years ago I reviewed the files of twelve juvenile murderers in an effort to detect a consistent pattern in their early criminal behavior. Some seemed to have sneaked up on the system, but more than half had long records of juvenile crime, starting in every case with simple burglary. To a child, they had been handed probation after probation for the break-ins. I wondered then, as I do now, if the current confusion about whether burglary is even a crime isn’t providing kids with a simple, accessible starter course in a criminal education.

The tendency of the courts to be more a part of the problem than a solution can also be traced to that well-worn law enforcement apologia: priorities. With violent crime on the rise—in particular, stranger-on-stranger violent crime—prosecutors and judges feel obligated to fill the courts and jails with rapists and murderers; once again, the system just doesn’t seem to have room for the burglar.

The bottom line here is that, for better or worse, burglary is our problem. What to do about it is a good deal less clear. There are as many theories about that as there are about why certain individuals become burglars in the first place. The most common panacea is to throw more money and manpower at the problem. This is a convenient and seemingly reasonable solution, but even assuming that government could persuade the public to cough up more money, there’s little indication that more cops would make much difference. As an experiment, patrolmen in Kansas City were doubled and even tripled in some sectors with little impact; in a Los Angeles study, it was discovered that a patrolling policeman was likely to detect a burglary in progress only once every few months. This is because of that most often ignored fact about crime: most serious felonies—particularly burglaries—just don’t happen in the presence of any third party, let alone a policeman. Contrary to popular belief, police officers rarely catch crooks; they catch up with them after the fact.

Exotic experiments with refashioning the way police officers go about their work have been, for the most part, similarly discouraging. Some dozen cities have tried “decentralized” and “team policing” structures with only moderate success. The basic idea was to eliminate the cumbersome “chain” approach to investigation—from a reporting patrolman to a fingerprint expert to one or several detectives—and to substitute teams of patrolmen and detectives who work the same neighborhoods every day. The concept no doubt improved intradepartmental police efficiency, but the most ambitious efforts in this regard, notably Cincinnati’s, have proved inconclusive as to their impact on crime rates.

A trendier notion is that of volunteer neighborhood “watches.” One of the more successful of such programs in Texas is run by the Bois d’Arc Patriots, an East Dallas community action group. Using money from a Justice Department grant, the group first did extensive “target hardening” in the most often burglarized areas: running security checks for residents, instructing them how to secure windows and doors better, teaching them about the habits of the burglar. Next the Patriots organized certain blocks into watches, assigning each resident particular duties: one resident might be assigned to walk out to the mailbox every other hour; another to check his alley. Burglary in the area decreased 5 per cent when only the year before it had been increasing at a rate of 12 to 20 per cent.

But Patriots leader Charlie Young says such programs are difficult to sustain and are successful in only a certain type of neighborhood. “Community crime prevention requires a couple of things that aren’t always easy to find,” he says. “You’ve got to have leadership assumed by certain people. Also, you’ve got to have people who are home during the day. In a city like Dallas, you don’t always have that.”

Neighborhood watches should be encouraged—50 per cent of all residential burglaries are accomplished via unforced or possibly unforced entry, and the least we the victims can do is cut down on that embarrassing figure—but I doubt they are a long-term solution to the problem. The public can go only so far in policing for itself; taking too much of the law into its own hands can only encourage more private handguns and more bloodshed between victim and perpetrator. Worse, it can subconsciously erode public confidence in law enforcement: why is it all our problem?

In recent years, some criminologists have actually proposed that we, by law, decriminalize burglaries that don’t involve any other, more serious crime. The best argument has been made by Canadian criminologists Irvin Waller and Norman Okihiro, who, after an extensive study of burglary in Toronto, concluded, “Faced by rising costs of policing and an expectation that crime will be reduced by police, the police and its selected representatives will be continually dissatisfied. Money, public frustration, and victim and property loss could all be saved, if police departments change their response to burglary.”

They go on to suggest that “less serious” burglaries—less than $200 in stolen property and damage done—be made a so-called summary offense, punishable by only a fine or some form of restitution to the victim. For more serious burglaries, they propose a compulsory “work penalty” and additional restitution. Once burglary is successfully out of the police departments’ hair, they say, the state should provide minimum insurance to all citizens, something on the order of the first $100 of each $1000 in losses. The basic rationale here is that most burglary victims don’t really care about the perpetrator anyway, and by focusing on the victim’s needs through mandatory insurance, the criminal justice system could be made more “cost-effective.”

If all of this is beginning to depress you that’s because it should. Proposals such as Waller and Okihiro’s are well intentioned, but they cleverly beg the big question here: can we afford to make the heinous act of one citizen’s breaking into the home of another no more serious an offense than running a red light? What’s next? Armed robbery where no one is hurt? Rape where there is no enduring physical injury? Modern criminal justice has become a slave of relativism. Today’s felony is tomorrow’s misdemeanor. But anyone who thinks residential burglary is not a serious crime should listen to what my wife said the evening after our break-in: “The worst part is that someone who doesn’t even care about my necklace that my grandmother gave me now has it, and I will never have it again. Why do they get to have it? Something’s gone that will never be replaced. I can’t imagine what it would be like to be raped. Or maybe I can.”

I don’t have any more answers than anyone else, but perhaps law enforcement, the courts, and we the victims could learn something from one Doris Grimes of Dallas. Grimes, owner of an aircraft parts supply company, might have been just another statistic after she was robbed to the tune of $100,000 in property in January 1978. The only difference between her and the rest of us is that Doris Grimes refused to feel lucky.

After hounding investigators for weeks, she received the glimmer of good news that most of us never hear—a few items that looked like hers had been recovered and a suspect was in custody. That might have been satisfaction enough for those of us who are into feeling lucky, but Doris Grimes wasn’t through. She not only agreed to press criminal charges against the two burglars accused of taking her property but she also filed a civil action against them and their fences to recover actual losses for the property she had not recovered and punitive damages on the principle of the thing. And she won. Thus far, Grimes has won a $175,000 court judgment from the burglars and a woman who bought the hot property, and she hopes to collect the money in the near future. She has not just recovered the value of her stolen property; in a sense, she has exacted the ultimate retribution against the strangers who decided to rob her home—she has forced them into the victim’s shoes. At least one of the burglars has had most of his earthly possessions—including some of his wife’s jewelry—impounded in lieu of payment. Among the property is a ring that he has begged Grimes to return because it is of sentimental value to his wife.

But what I like about Case No. 78-3591-I, Doris J. Grimes v. Her Burglars et al., is the fresh air it breathes into a law enforcement system and a victimized public that have become jaded by the inexorable odds of crime. She just got mad as hell and decided she wasn’t going to take it anymore. That’s got to be a lot better than feeling lucky.

Your Best Bet

Short of electrified fences, armed guards, and a mine field in your lawn, here’s what you can do to discourage burglars.

If someone wants in your home badly enough, he’ll find a way. There is no certain method for preventing burglaries, but there are things you can do to reduce the odds. Here are some basic dos and don’ts for safeguarding your house against burglars:

•Make sure all doors and windows are securely locked at night and whenever you’re not at home. This should probably go without saying but even homeowners who have elaborate burglar alarm systems have been known to leave the front door unlocked. And make sure all your locks are sturdy one-inch dead bolts. Again, if the burglar wants in badly enough, he’ll get in. But burglars are essentially lazy criminals; anything that makes the job a little harder is likely to send a would-be burglar looking for an easier mark.

•Invest a little money in exterior doors that have solid cores. In new housing developments, especially, developers have been known to cut corners and outfit homes with hollow-core doors, which can be kicked in by a healthy child. Check the framing around doors and windows too; some framing is so flimsy that a door can be pried open with a screwdriver.

•Alarm systems are obviously a deterrent, but before you decide to invest in one, check with your police department’s crime prevention unit. Not all alarms may be for you or your home.

•If your home is frequently unattended during the day—some police officers attribute at least part of the current burglary upswing to the increase in working couples—leave a light on in a conspicuous place. Some officers even suggest leaving a TV set on to add to the illusion of human presence. If you’re worried about the few dollars this might add to your electric bill, rig the lamp or TV with a timer so that it switches off and on intermittently during the day. Again, this won’t stop a burglar outright, but it may raise enough doubt in his mind to move him over to the next block.

•Take the time to mark all your valuables with the driver’s license number of the head of the household. Most police departments have community service officers who can assist with this. The benefit here is threefold: First, marked merchandise may be enough to stop the burglar dead in his tracks because pawnshops aren’t likely to buy it and even fences may shy away from it. Second, marked merchandise is easier to trace. If the burglar does successfully sell the property to a pawnshop, the odds are good that it will turn up on police computers. Third, marking your valuables virtually ensures that you won’t have any right-of-ownership hassles if your stolen property turns up in a pawnshop or a fence’s warehouse. Remember, just saying you know it’s yours often isn’t enough; the police are required by law to have proof of ownership before relinquishing recovered property.

•Don’t build a tall, fortresslike fence around your land thinking that it will deter burglars from even casing your house for a break-in. High fences, in fact, may make your home more attractive to burglars: once in the yard, the burglar can rest easy that neighbors or patrolling policemen can’t spot him.

•Try to resist the temptation to buy a gun. It’s hard—I found myself perusing the gun shop ads for about a week after my burglary—but the police say that having a gun around can increase the chances that a burglary will turn into something worse. Most burglars will run at the slightest hint that someone is home, so a weapon is unnecessary. On the off-chance that you actually do confront your burglar face to face, pulling a weapon on him could backfire on you. If you, like me, are generally unfamiliar with firearms, you could make any one of a number of serious mistakes; worse, if a struggle ensues—burglars are considered docile criminals, but they can turn mean when confronted with a pistol—you could find yourself on the wrong end of the gun.

•Above all else, the police say, try to get to know at least one neighbor well enough to work out some kind of cooperative surveillance arrangement: he keeps an eye on your home when you’re away and vice versa. Large neighborhood-watch organizations are understandably difficult to maintain; if nothing else, the sheer turnover of residents in cities like Dallas and Houston makes such groups unfeasible. But maintaining a relationship with at least one neighbor could result in catching your burglar in the act. J.A.

- More About:

- TM Classics

- Longreads

- Crime