This story is from Texas Monthly’s archives. We have left the text as it was originally published to maintain a clear historical record. Read more here about our archive digitization project.

I have never considered myself a gizmo person, in or out of the kitchen. Of course, if I perceive a particular need, I always attempt various solutions until I find a remedy. This experimental fervor, this lust to get a hard job done just right, is what drives me to buy any new piece of kitchen equipment that claims to slice a rare roast or jimmy a cork from a bottle. If you wish to call such high-minded dedication to problem solving an interest in gadgets, you are at liberty to do so.

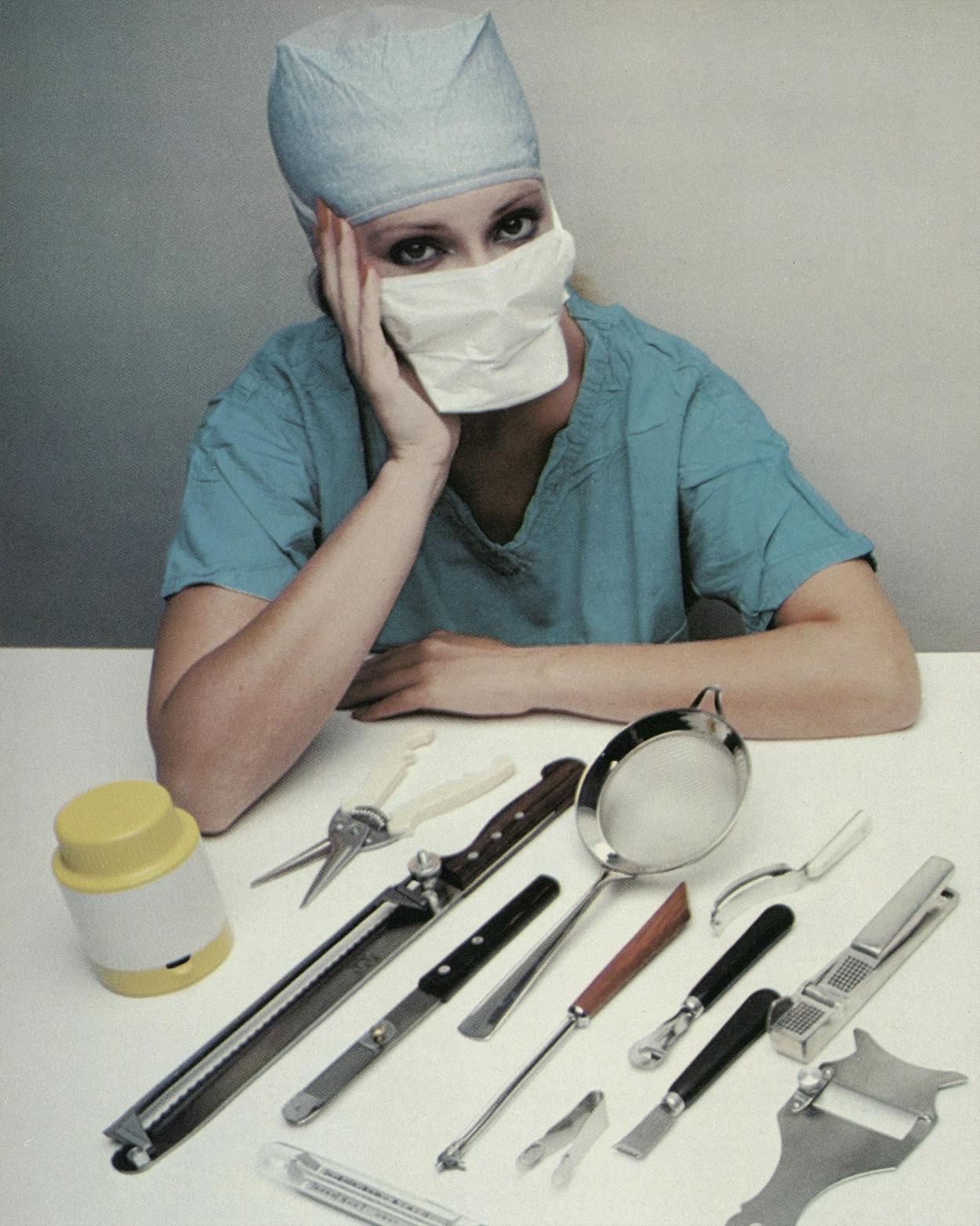

This problem-solving attitude is the only sensible one with which to evaluate the proliferating apparatus that now clutters most kitchenware stores and all too many kitchens. The key is to discern what is useful and what is not. To someone who has not yet perceived a particular need this can be difficult—all gadgets seem ridiculous. Few of us, for example, have felt the need for a Japanese bean curd knife or a bean curd server, but then few of us eat very much bean curd. A gadget is merely an invention—sometimes an almost miraculous one—to do a job you wouldn’t do otherwise, or else wouldn’t do very often because it would be too much trouble. And a favorite gadget is going to be a personal thing, because it will be able to solve a pet problem. Over months of testing, I have experimented with four dozen gadgets that claimed to solve my worst kitchen dilemmas. As an average American male who likes to cook, I assume that a lot of people suffer the same frustrations I do. Here are my favorite solutions to my most perplexing problems.

The Perfect Egg

One problem that heretofore has had only crude solutions is the soft-boiling of an egg. If you live with a soft-boiled-egg addict—as I do—you know how seldom the perfection of a firm white and a just-thickening yellow is achieved. The traditional three-minute egg, cooked by using a timer, is usually satisfactory, but in order to certify any egg as such you have to be on hand to start the timer just when the water reaches a boil. It is simpler, and more reliable, to use the Good Egg ($6), a thermometer assembled by Sybron/Taylor in Juárez. The only skill this little scientific wonder requires is an accurate estimate of the relative size of an egg, since the thermometer is calibrated into readings for small, medium, large, and extra large. Even more impressive to me than its knack of soft-boiling an egg is its ability to hard-boil one. With the Good Egg, you can infallibly produce a hard-boiled egg that is just done, without the gray rim around the yolk that is produced by over-cooking. I have tried all sorts of techniques to accomplish this, but this handy, if fragile, thermometer is the first gadget I’ve ever trusted.

Coup de Fruit

There is an enormous assortment of gadgets designed to cut corners in the preparation of fruits. One of the most popular is the apple slicer—a wagon wheel of metal slicing blades mounted around a central hub, which eliminates the core. A sturdy version, the Westmark Divisorex ($7), is indispensable to apple-eaters like me who prefer eating bite-size slices to tackling a whole apple, even though the contraption sometimes misses part of the core. Far cheaper—the cheapest gadget going—is the strawberry huller, a simple tweezerlike device vaguely resembling the cricket noisemakers of our childhoods. It costs 40 cents, and it really does lift the hulls off strawberries faster and more efficiently than a knife.

There is one particular fruit I value for cooking more highly than any other: the lemon. It also poses me greater dilemmas. The first problem with a lemon, of course, is its rind. A knife or a vegetable peeler, not to mention a grater, takes off too much of the white along with the yellow, which taints the delicious oil of the lemon zest with the bitterness of the flesh beneath it. A number of gadgets claim to deal with this. Don’t be fooled by the Efferi sbuccialimone ($6). This frightening instrument—it looks like a villainous straight razor—takes off the whole peel. You might find it useful for a recalcitrant orange, but it won’t help you skim off exactly the right amount of lemon rind.

Two little French peelers made by Econome are far superior. The cheaper, at $2, has a single hole that removes a strip of the zest about three-sixteenths of an inch wide, most suitable for garnishing a cocktail. The other, at $3.50, has a row of five tiny holes at the business end. When scraped against the lemon, these produce the most delicate strips of lemon peel obtainable. When very finely chopped, these strips are the absolute essence of lemon.

Once I get past the skin, the lemon still gives me trouble. Lemon juice is one of the commonest flavorings, but most recipes call for just a few drops of juice, so almost every cook has a partly squeezed lemon half slowly rotting in the depths of the refrigerator. Good news! Those days are gone forever. One of the loveliest of gadgets is the Ritter Citroboy ($9.75), a cylindrical plastic container hiding an old-fashioned plastic citrus squeezer between a screw-on lid and a screw-on bottom. Insert a half-lemon between the squeezer and the lid, and you can have lemon juice by screwing down the lid. The juice falls into the screw-on saucer and can be poured out and measured conveniently. The partly used lemon half is simply stored as is within the gadget.

The Slice of My Life

I would be the greatest cook living if I weren’t so clumsy. My lack of physical dexterity not only ensures that my kitchen resembles a Jackson Pollack canvas when I finish cooking, it also means that a knife in my hand is a prelude to butchery. I especially flub when it comes to carving and slicing. I have tried most of the ways available to cheat my way out of this situation (including the much-ridiculed electric knife), but to little avail. I was excited, therefore, to come across an Italian invention, the Montana adjustable slicer ($20). This is a regular stainless serrated slicing knife, with the addition of a Teflon-coated adjustable bar to guide eyes and hands like mine. The Montana knife works wonderfully on just about anything cold. Now I can slice bread, cheese, most cold meats and fruits, even tomatoes, with utmost regularity to whatever thickness I desire. I assure you that tomato slices a sixteenth of an inch thick, coming from my hands, are most remarkable. But the slicer doesn’t work very well on mushy textures like liverwurst, nor does it solve my carving problems. The serrated edge is not appropriate for hot meat, and the positioning guide means that all cutting must be done on the edge of a board so the knife can slice clear to the bottom of what’s being cut. It is very difficult to find a convenient way to slice a rare, juicy roast on the end of a board. A useful gadget, but for me it doesn’t solve the right problem.

Very similar in principle is the Dreizack Trident asparagus peeler ($15.50). Everybody knows that the tastiest way to cook fresh asparagus is to peel and then steam it. Almost nobody does it, because to take off just the right amount of peel takes time and a steady hand. Again, a vegetable peeler just won’t do (in this case, it takes off too little peel). The Trident asparagus peeler is the solution; you adjust it to take off just the right amount of peel (I find that the maximum width is easiest to use). Best of all, the job goes quickly and doesn’t require concentrated attention. The cook can easily peel a big bunch of asparagus while watching the evening news, and that means that a lot more peeled asparagus will be eaten in our house from now on.

A third adjustable slicer looks extremely glamorous, but I fear its uses are too few for my kitchen. The tagliatartufi, the Italian truffle cutter ($12.50), is designed to shave white truffles thinly for garnishes and sauces. I don’t see nearly as many white truffles as I would like, and I don’t even have much call for shaved chocolate, which is the other vaunted use of the truffle cutter. The elegant little shaver, when properly adjusted, does cut attractive slivers of cheese, but they are far too thin for my taste. If you are interested in a cheese slicer that works, invest in the Dansk ($6), a wire strung tautly around a five-inch metal contraption mounted on a wooden handle. Draw one side of the contraption over a cheese, and the wire cuts a thin slice; the other side slices a more generous portion. I am not crazy about cheese slicers (I prefer to bite into hunks of cheese), but the Dansk has made a convert of me because of the reliability of its operation and the even slices it makes.

Getting the Fat Out—and In

In my cooking career I have skimmed very little fat successfully or happily with a spoon or bulb baster. Now there’s an intriguing gadget available that makes this nasty chore at least possible. The Colony Cup ($6.50) looks like a clear plastic measuring cup with a removable white plastic strainer on top. On the bottom there is a white plastic pull-tab that lets the liquid in the cup flow out from the bottom. Any fat in the liquid will collect at the top, so all you have to do is stop the flow of liquid right before the fat gets to the hole. You will be amazed when you take a skimmed soup or sauce from the refrigerator and find no congealed fat on top.

Rich cream poured over fruit or blended in a sauce is undeniably a peak in the realm of culinary experiences. Peak, that is, if you can find cream that tastes like cream. Most “cream” these days is ultrapasteurized for a long shelf life, but an English gadget called the Bel cream maker ($13.95) provides an alternative: it reconstitutes cream from milk and butter. To accomplish this you pump melted butter and milk through tiny holes into a plastic container, thus rehomogenizing the two. The result is a fresh and buttery-tasting cream that keeps for several days in the refrigerator without separating. There are several drawbacks, though. The adjustment of the screw that sets the opening is critical, and fiddling with it after you start the process results in greasy hands. Vigorous pumping is required in order to force the liquid through the holes, and by the end of the job you may feel as though you had milked a real cow to get your cream. And if you pump too vigorously, you will have a big mess on your hands and all over your kitchen. I have also been unable to properly whip the whipping cream made with the suggested proportions of butter and milk.

Salad Days

The secret to a perfect salad is dry greens (wet lettuce waters down the dressing), and for the sake of perfection I have used enough paper towels to reach from here to Chicago. I have also, when feeling especially athletic, watered the front yard on many an early evening by whirling around a wire basket full of wet greens. The expense and the effort involved in these two methods pricked my interest in several recent elaborations on the plan of drying lettuce by means of centrifugal force. In these contraptions, a plastic basket rests within a larger plastic container with holes in the bottom. The larger container keeps the water from going all over everything (no more forays out-of-doors in the dead of winter or heat of summer), and the various means of propulsion—usually a yo-yolike apparatus or a hand crank—eliminate pitching practice before dinner.

The most unusual of these devices is the Cogebi vegetable washer from Belgium ($15), which has a large open spout to admit water, so that you can clean as well as dry vegetables. As a dryer, it rates excellent marks, and as a washer surprisingly good ones. You can’t expect to fill it to the brim with sandy leaf lettuce and have perfectly clean greens after a few whirls, but if you do the job in batches, your greens, especially dirty spinach and turnip greens, will indeed come clean.

A good salad usually wants garlic in its dressing. Purists would chide me, but I have been known to forego mashing or mincing garlic in favor of using a garlic press. As you probably know from sad experience, the difficulty with pressing garlic is that you pay later for the momentary convenience. A garlic press is harder to clean than any other object known to humankind. My wife, a study in patience, has been known to ream out every one of those tiny holes with a toothpick. I am more inclined to leave the press sitting around until the garlic rots away. The Rowoco self-cleaning garlic press ($7) solves the problem of getting out the residual garlic. The press hinges in two directions; pressed one way, it acts like a regular garlic press; pressed the other, a grid of tiny spikes matches the grid of holes, which pushes the lingering particles of garlic out and away. The self-cleaning action, in fact, is likely to prove less questionable than how it fulfills its primary function. Because of the tool’s design, a substantial portion of each garlic clove will not go through the holes at all, and the frugal might be bothered by the waste. The pressed garlic also comes out more chopped than mashed—but frankly I find this texture more desirable.

Wine Without Tears

I have had a longtime fascination with wine, and hence with instruments designed to extract corks from the bottles. I have tried them all, including one rather startling device that stabs the cork with a spike, through which air is pumped until the cork pops out. It, like most of the fancy cork removers of my experience, does not work very well. The exception is the Monopol Ah-So cork puller ($5), which is simply a handle attached to two gently curving prongs. Insert the prongs between cork and bottle, rock back and forth until they reach the end of the cork, then twist the cork out of the bottle. The Ah-So is very good at doing its basic job, especially on old corks that might crumble if manhandled with a regular corkscrew, but its real forte is getting the cork back into the bottle. There are many times when it is necessary to recork a bottle of wine, but the project can be difficult. The Ah-So makes recorking just as simple as uncorking.

One of the problems with many corkscrews (especially the air-pump spike I mentioned) is that instead of pulling the cork out of the bottle, they push it in. Nothing is quite so frustrating as watching a cork bob in the burgundy, daring to be retrieved. Perhaps the most heartening of all gadgets is the one that enables you to do just that: the PPL cork retriever. This gadget looks so simple—it is a slightly concave metal bar with a spike on one end and a handle on the other—that you will never believe it can do the job. But once you have seen it in action you’ll have to have it, especially since it costs only $1.25. Since the cork retriever is so cheap, you might consider buying at the same time another hedge against disaster, a superfine strainer by Efferi ($11), which will filter out any little bits of cork that may have been dislodged during the opening.

The Ultimate Gadget

After exploring many different kitchen contraptions, I have settled on one that ranks as the absolute ultimate. Like the others I have been discussing, this one is a specialized tool that does its task better and more conveniently than any alternative. Unlike the others, which eschew electricity and instead stress the cook’s active participation, this one plugs in. It is the Minigel, a completely automatic, self-contained ice cream maker imported from Italy. Besides a motorized set of blades for turning the ice cream, it has its own freezing unit. Unlike most electric ice cream machines, it requires neither salt nor ice nor a refrigerator freezer.

The Minigel has a regal look (those Italian designers know their stuff). It is about the size of a travel cage for a dachshund and weighs approximately 25 pounds. When the single switch is touched, the only visible motion is the revolution of the dashers. The Minigel does have a few quirks. It is rather particular about the amount it will freeze. If you freeze too little ice cream, some of the mixture solidifies too quickly, and you will have a hard job of scraping it up. If you put too much into the machine, freezing time slows down from twenty minutes to well over an hour, and the ice cream may swell enough to lift the plastic cover.

The dashers can be easily removed for cleaning, but the freezing container stays put. Since you doubtless will devise a method to devour every smear of the quart of ice cream the machine produces, cleaning the bowl in situ should be no grave problem. Of course you pay a fancy price for this luxury—$675, high enough that the people at the Dallas branch of Williams-Sonoma, the only U.S. vendor of the Minigel, say that a number of machines have been bought by consortia of families who pass their Minigel from house to house.

To my mind, the Minigel is like the asparagus peeler. Its simplicity and convenience allow a rare event to become an everyday possibility. The creative cook can also multiply the Minigel’s uses. Almost any fruit or vegetable is a candidate for sorbet—I have tasted melon and avocado and have heard tell of a frozen gazpacho. Maybe I’ll give asparagus a whirl.

- More About:

- TM Classics