This story is from Texas Monthly’s archives. We have left the text as it was originally published to maintain a clear historical record. Read more here about our archive digitization project.

I should have stopped taking them the first time I took two instead of one, three instead of two, four instead of three. I knew perfectly well about tolerance, the body’s tendency to need more and more of a drug just to keep getting the same physiologic effect; I saw it working on some of my patients. But I wasn’t a patient, I was a doctor. It came as quite a shock to realize something I had learned in class applied to me.

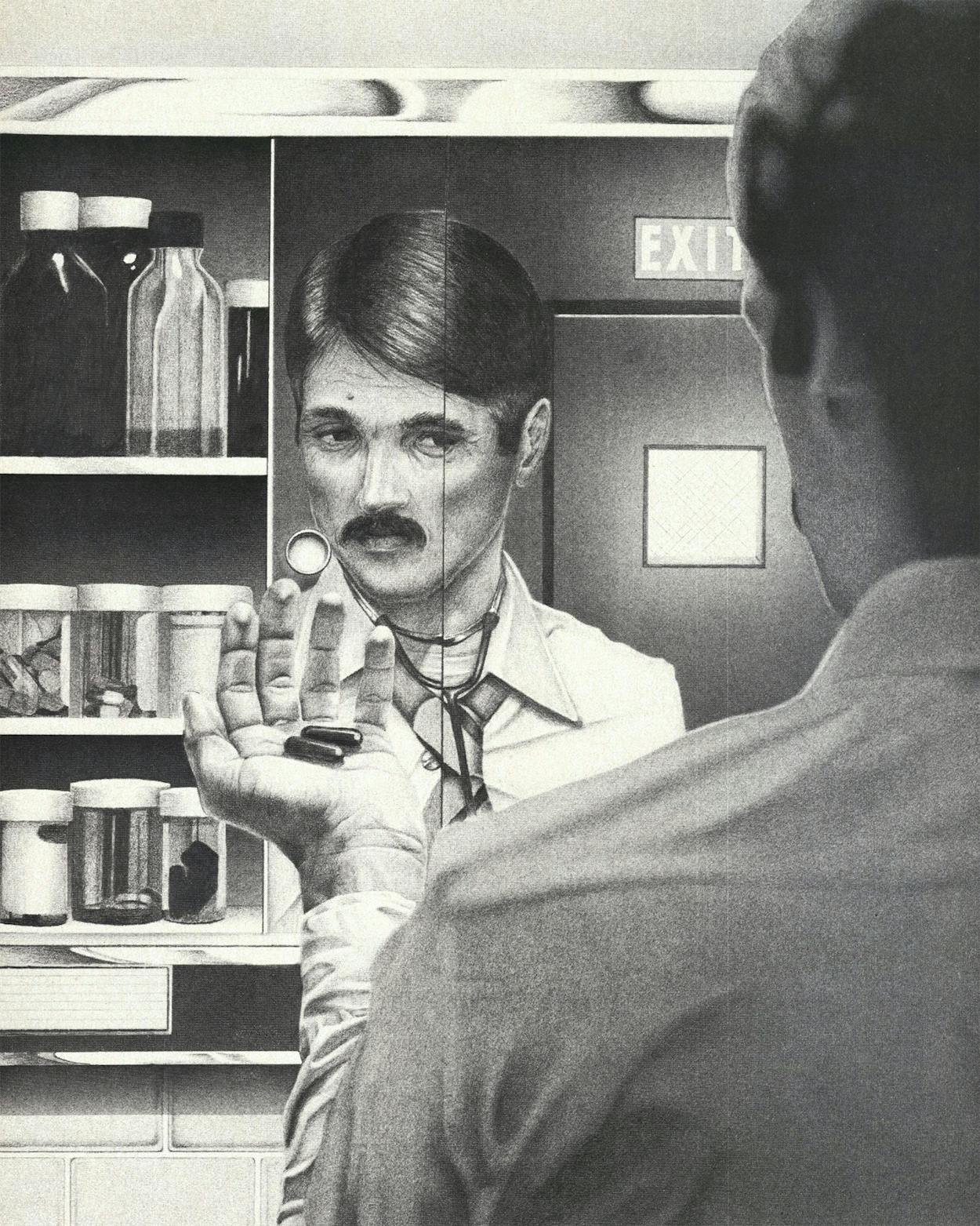

Besides, taking pills is as American as apple pie. As a medical student I remember thinking I had finally arrived when I was able to sit down with a patient, take a history, do a physical examination, put down a list of possible causes of each symptom, and then prescribe a drug as treatment. It was all such a nice, neat package. Something for constipation? Okay. Something for sleep? All right. Something for nerves? I can fix you up. Something for the blues? Sure. Now, what else?

Fellow undergraduates at the University of Texas had told me they sometimes took pills to stay up all night before an exam. I was naive. Pills to keep you awake? Surely there was no such thing, and besides, I was so methodical in my study habits that I didn’t need them. The same was true for medical school, but internship was different. By then I knew that there was such a thing as a pill to keep you awake; I also had discovered that I regularly had to stay on my feet practicing medicine for 24 to 36 consecutive hours.

At many hospitals the intern was through with emergency room duty after a block rotation of several weeks or a month. I interned at a city-county hospital in Texas for a year in the mid-Sixties, and since there were only eight interns and no residents, each of us pulled a 24-hour emergency room call every eighth day. I’d show up around 7:30 a.m., start clearing out the few patients left over from the night before, take care of new patients, and then be off to make the rounds on my own patients. The day nurse and technicians on duty when I got to the emergency room were able to handle most of the morning patients. But not everything. People came in with kidney stones, or heart attacks, or gunshot wounds. One morning a kid came in choking. I rushed into the ER; the mother was hysterical and wrestling with the nurse while the technician was trying to suction the child’s throat. On impulse I swung the two-year-old into the air by his feet and hit him on the back, dislodging a large wad of bacon. I was writing a note on the chart when two orderlies wedged a lifeless form on a stretcher into the room. The man was not breathing. His eyes were closed, his mouth was open, and his face was the color of faded newsprint. I had to go outside and tell his family he was dead, but was interrupted by the wail of a siren and the arrival of three people who’d been injured in a car wreck. While I was examining them a woman arrived who’d given birth in a taxi en route to the emergency room.

After eight hours of this sort of chaos, the day shift left, to be replaced by a bright-eyed crew at 3 p.m. They wanted to get things rolling, and would call me from the wards, from the clinics, or even from surgery. One day during the course of an appendectomy I treated a case of strep throat and two women with urinary tract infections without ever leaving the side of the operating table. Evenings were busiest of all: people came in wanting treatment for fever, dizziness, gonorrhea, pyelonephritis, pneumonia, colds, rashes, pain, breathlessness, and headaches. The afternoon nurse and technician left at 11 p.m., to be replaced by a new crew, the third of my day. By that time of night I was desperately tired, a zombie who still had to smile and make competent, compassionate decisions on matters of life and death.

The police played a big part in nighttime business. They might bring in a guy and request a shot of Thorazine to calm him down. That sounds easier than it was. A reluctant patient on his way to jail does not exactly roll over and dutifully offer his bum to the nurse; with shouts and screaming, he’d have to be fought into submission and might shit on the stretcher out of spite. The night passed while drunken men made phone calls, accident victims waited for x-rays, sirens in the distance announced the arrival of more business. I simply got tired. Grew surly. Around 2 or 3 a.m. my vision would blur and I had trouble keeping stitches straight and skin edges everted. But good job or poor, I never lacked for customers. Above the cacophony of ringing phones, laughing people, and groaning patients, I wanted to shout, “Hey, you guys! I’m a goddamned doctor, don’t drive me into the ground! I can only do so much!” Of course I didn’t complain. I kept going.

Across the hall from the emergency room was an intern’s lounge, where the intern could sneak over to use the bathroom or to snatch a little rest if things quieted down after midnight. A sofa was right next to a little table with a phone where you could stretch out and maybe even go to sleep. I rarely slept though, because as soon as I’d get still the phone would ring. “I’m sorry to bother you, Dr. Deaton,” the musical, accented voice of Mrs. Lopez would say, “but we have here a man who says he is short of breath. Police was taking him to jail and brought him by for you to check. And there is this woman here who wants for you to put her a check of her blood pressure, and I hear an ambulance. Can you come right over?”

I could have called out another intern to help, but you handled it when you were on duty, just like he handled it when it was his turn. I needed help, but I didn’t need to call another intern for it. Along with the phone, the sofa, and the bathroom, the intern’s lounge also contained a drug locker. And in the drug locker were lots and lots of drugs, including a selection of several different brands of pep pills.

I was psychologically hooked from that initial geeze. It was as though nature had inadvertently neglected to supply my system with the required ingredients. Heroin was the missing chemical that made me a complete human being. Suddenly, all the soul-pain was gone. I felt right and light and aware and calm. There was an inner peace at the very core of my being. I was alive!

Chic Eder, in Ladies and Gentlemen—Lenny Bruce!!

That pretty much describes my initial reaction to pep pills. It was about midnight, and I was tired, but the pill set me free! I became acutely aware of every part of myself. The very hairs on my arms emitted a pleasant sensation. My clothes felt good on my skin. My hands were perfect—steady and able. The pill gave me a new awareness of my own existence, of my own worth, of my own sense of being. Surely this was the way life should be. Pep pills, or speed, stimulate the sympathetic branch of the central nervous system, and produce what is known as the “fight or flight” response. The brain and spinal cord buzz with excitement. The heart beats faster, blood pressure goes up, goose bumps break out on the skin. Speed makes one feel alert, ready for anything. With this all-out reaction comes a glorious feeling of happiness. Under natural conditions this euphoria is the “laughter in the face of death” often noticed among soldiers just before a battle. My battle was in the emergency room, and five minutes after taking the speed I was the happiest conqueror on earth. I felt good, capable, strong, and energetic. I was trustworthy, loyal, helpful, friendly, courteous, kind, obedient, cheerful, thrifty, brave, clean, and reverent. I was sensational.

All of a sudden with a pill on board I could not do enough for other people; it was my delight to serve them. Emergency room duty? No sweat! My coordination was better than O. J. Simpson’s. Power surged into my tired legs; I felt like it was the first fresh day of spring. Talk? When tired, I ordinarily clam up like a lizard, but release me with a pep pill and the sentences would spin out of my slack mouth and bring to the faces of my reassured patients smiles of gratitude that they were, after all, going to get what they had come to get: balm. I had plenty of balm, and I was the biggest balm of all.

The pills became a habit.

They were left in the intern’s lounge by the drug detail men, left there not necessarily for the personal use of the physicians, but who was to know what you did with them? The drug locker was in the bathroom, so that you had an excuse to lock the door while you picked and chose among the pills. For my part, all I had to do was put a Preludin (similar to Dexedrine in its effects) on my tongue, scoop a handful of water from the lavatory, and swallow. The pill did the rest. Pooped, I’d duck into the lounge, pop a pepper, and zip out like Clark Kent become Superman. Nights on call I took peppers like a prescription, one every three to four hours as needed for energy.

Why didn’t I see what was happening and stop the first time I needed two instead of one, or three instead of two, or four instead of three? The all too easy answer I gave myself was that I needed them to do my job. I was an achiever. Set a task and I could accomplish it. The end doesn’t justify the means? You couldn’t have proved it by me. I was asked for medicine, gave medicine, took it myself. We were all in this together, the patients and I, and I wanted to hold up my end of the bargain. At first taking pills bothered me, but I did not let my mind dwell on it; I took the pills because they were there and I needed them; I took them because I took them.

The bad thing about taking uppers is what the pharmacologists call poststimulatory depression. After every high there is a low. The low with pep-ups came the next day: my eyes would redden from lack of sleep; my bowels would lock from constipation; my urine, yellow as that of a patient with jaundice, would reflect my lack of fluid intake. I’d wake up on a real downer, and to take the speed the following day seemed the only reasonable course.

Practicing medicine was not anything like I had imagined. For one thing, my patients did not always love me. Quite the contrary. I was the most tangible link in the sickness-treatment chain, and when recovery was not forthcoming, I was apt to be blamed. One day, bleary-eyed after a night on call, I was waiting outside the hospital for my wife to pick me up. A lady nearby was waiting for a bus. She saw me, and to my amazement, hurried over and started hacking at me with her purse. In between blows I ascertained that I had seen her last night; she was angry because I hadn’t admitted her to the hospital. A hard blow to the face spun me around, and I balled my fists and prepared to attack. “Leave me alone!” I growled. She covered her retreat by spitting at me. “You doctors are all the same,” she shouted, “full of shit!”

Many patients seemed to blame their problems on my lack of curative ability. They didn’t want to lose weight on their own, they wanted fat-melting medicine. They didn’t want to stop smoking, they wanted a magic cough syrup. They didn’t want to eat right and drink plenty of fluids to prevent constipation, they wanted laxatives. And when the drugs didn’t work, it was the doctor’s fault.

I went into medicine thinking it would be like football. I knew I wouldn’t win every time, but I at least expected to move the ball, to kick well, to execute the fundamentals of the game. Instead, very often I had to sit on the bench and still take the blame for the team’s loss. And then there was the problem of death. At the hospital, when someone died, I felt guilty. To avoid this feeling, I went to great lengths to save the life of every patient, even the terminally ill ones. Older doctors, even some of the interns, were able to take the loss of a patient in stride. They appeared calm and dignified, explained that everything possible had been done, and gave what comfort they could to the grieving relatives. I played this role myself, but hated it. In telling of a patient’s death, I felt that I was admitting my own failure.

Pep pills changed my outlook. I had never been particularly gregarious, but with some speed in me I was the life of the party. Despite the dry mouth the pills caused, I could talk endlessly. I remember one time my in-laws were visiting. They had brought with them the driest, toughest roast beef in South Texas, and they couldn’t understand why I preferred to sit talking and sipping Pepsi while they ate. It was my duty to get up for people; I felt they expected me to entertain them. I was lost without my peppers, and began to wonder which self was the real me—with pills or without? I decided I wasn’t my true self until I had taken them. They were indeed the missing chemical that made me whole.

Who was doing this to me, and why? I knew I was in a trap, but getting out of it was something else. Still, I did. A few months after I’d gotten hooked, I weaned myself of speed. It wasn’t a complete break, because I would still take pep pills now and again, but I no longer needed them to get through a night on call. The glow of confidence at quitting one habit blinded me to the onset of another.

A detail man had provided each of us with a generous selection of his company’s sleeping pills. I went by the lounge one day to find my gift in the stack with the other interns’. It was like a Whitman’s Sampler. Through the plastic lid shone capsules of Seconal, Amytal, and Tuinal; bright capsules of red, blue, and blue-and-red; gelatinous containers of secobarbital, amobarbital, and a mixture of these two barbiturates. I seriously doubted I’d ever need them, but took them home to the closet shelf, where they were waiting for me when I began to have trouble getting to sleep.

Stimulants caused insomnia, and I dreaded the weary, red-eyed day after. One way I avoided it was to take more speed; another course of action was to grab a sleeping pill. I was surprised to find, however, that even after I stopped the speed I still had trouble falling asleep. The hospital and what was happening there were in my blood, and I couldn’t escape it even at home. I worried about patients. I fretted. I retraced my treatment and its effect, and worried some more. The worst thing was finally to fall asleep, then be awakened by a phone call from the medical or surgical ward. Someone’s blood pressure was down, or his fever was up, or his pain was worse. Even if I didn’t have to leave the house I would lie there and worry about the patient. Toss and turn. A sleeping pill was a natural antidote, though I soon learned that if I took the Seconal late at night I faced the next day with a barbiturate hangover. Better to take the sleeping pill at bedtime on a regular basis, like a toddy. One at bedtime, PRN sleep. The kid doesn’t smoke or drink, see, and he needs something, no, he deserves something to unwind. Besides, he’s going to stop tomorrow, next week at the latest.

It should have worried me the first time I took two instead of one, three instead of two—well, here we go again. Tolerance occurs with many drugs, sleeping pills included. Actually, I did pause the first night I found myself reaching for a second sleeping pill. I remember it well. By now I had a bottle of the redbirds, and I got them out of the hall closet for a moment of scrutiny in the overhead light. In the bedroom slept my wife, blissfully as always. The bottle I was holding against the light was labeled Seconal, 100 mg. caps. I knew the little red capsule I held in my palm was 100 milligrams, but surely there had been some mistake. It looked so small, so absolutely tiny. Could it be only 50 milligrams? Yes! That was it, of course! In shipping or packaging the drugs a mix-up had occurred. These were only 50 milligrams, and you had to take two to get the effect of the 100 milligram size. So I took the second capsule. Tossed it off without another thought, because all I was doing was making up for somebody else’s mistake.

I had always made good habits and stuck to them. Bad habits were easier to make. They warned us about drugs in medical school. The movie they summoned us to see during our sophomore year was promoted with the fanfare: “No medical student who has seen this film before graduation has ever gotten hooked on dope.” The film, which featured a general practitioner who “gave in” one night and injected a dose of Demerol into his leg, made the following point: Don’t ever take that first injection! Boy, I thought as we left that day, I’ll never do that. And I didn’t. I never did inject myself with anything or take what I considered “dope.” I thanked my lucky stars for that, as night after night I bit the red curse. The number of pills I needed to get to sleep began increasing.

An old medical saying goes “Physician, heal thyself.” As a medical student, I gloried in this admonition, because it meant that a doctor should practice what he preached. Who isn’t repulsed by a fat doctor chiding an overweight patient? Or one that smokes telling someone else to quit? But with my dependence on pills I began to detect a cynical, leering message of mockery in physician, heal thyself. The words seemed to imply: if you can. But you can’t, you sonofabitch, can you? And if you can’t heal yourself, how are you ever going to help anyone else?

One night I vomited in my sleep and was too groggy to turn over; my wife saved my life by getting me on my stomach. The next morning I refused to look at the wretched red stains on the bedroom wall—but she insisted. She also demanded an explanation. Sadly, I took out my pills from all their hiding places, and we held services at the commode. Even flushing the Seconal down the toilet was a chore. They kept popping to the top of the swirling waters, kept floating to the surface for one more breath of life. Two or three days later I noticed some twitching in my legs. Suddenly, sitting quietly, I was startled by a series of jerks and twitches that ran the length of my body. I had a vague idea that this was related to my having gone cold turkey on the red men, but I didn’t give it a lot of thought. The relative ease with which I quit the sleeping pills was deceptive.

Residency came; we returned to Galveston for three years of training in internal medicine. I was one of the lucky ones given military deferment, which let me finish my training as a specialist before I entered the service. A year passed, two. Patients lived or died. Some of them had a great effect on me. I presided over the death of a 22-year-old black woman with leukemia. She was the mother of six children, one almost every year since she was fourteen, and she was pregnant with a seventh. I worked her up when she was admitted to John Sealy, and the morning we went in to tell her what the bone-marrow test had revealed, that was the morning I fell in love with her. “Mrs. Jones you have leukemia,” the staff hematologist had boomed out, “acute myeloblastic leukemia.”

“That’s pretty bad, huh?” Stella asked, turning to me. “Is they a cure for it?”

“No,” the staff man was quick to say. “No cure.”

“Well, it’s not for me I was worried. It was for my baby.”

“Why’d you talk to her like that?” I asked the hematologist when the sentencing was over and we were outside the room. “You’ve destroyed her hope.”

“She’s in for a rough time, and there was no other way. We’re going to need her cooperation.”

Stella did eventually deliver a healthy boy, but not until she had lost all her hair, developed foot drop and wrist drop, and almost died several times. After she left the hospital I followed her in the clinic. And then she was admitted for the last time. She died quietly, and since another resident was in charge of the women’s ward, I didn’t have to tell her relatives that she was gone. But who was to comfort me? I walked outside that afternoon and tried to take stock of myself. I was 27 years old and I was a physician. I had gotten good at it and was respected for my skills, but they weren’t good enough to keep Stella from dying. I wanted out, but the only freedom I could find was in a bottle of red capsules.

I reported to the Armed Forces Examining Station in Houston for my preinduction physical in 1966, a year ahead of schedule. After the examination, I filled in a form saying I would volunteer to serve in Viet Nam. I became convinced that I would die there. Even when I took sleeping pills, I twisted and turned in my fear. Sometimes my palms would sweat like sluices had broken loose in my wrists. The only consolation Viet Nam might offer was that with death would come sleep, blessed sleep, which would have been all right except for one thing: miserable as my life was, I didn’t quite want to let go of it. It was my curse to dream the dreams of a hero, and sweat the sweat of a coward.

“You’re taking it so good,” said a friend who happened over the day I received word that I was assigned to Viet Nam. The friend didn’t know about my support. That night I locked myself in the bathroom, let fall into my mouth six Seconals, and stuck my tongue out at the mirror. Looking at the tiny red coffins and then at the person in the mirror, I tried not to think about what had happened to me—or what lay ahead. I waited impatiently for the sleepers to take hold, waited for the sweet zap I had grown to anticipate. It was a comforting electric jolt that zinged through my arms and legs to let the peripheral parts know that the red men had boarded ship and were about to shift me into low gear. Taking sleeping pills was a way of recharging my body, and my entire day was a crescendo that built up to the barbiturates. The downers slowed the same processes that the speed had stimulated. They cut down on my coordination, but eased my tensions, kept me from caring. They made me drowsy. They gave me sleep.

I took them every night, and this meant carrying along a supply of sleepers when we visited relatives or went on vacation. I could no more have done without them than I could have done without water, or food, or rest. Sometimes when I gulped the small handful of capsules they would catch in my throat, and kick and scratch before descending further, as if refusing to do their rightful job. Then, I’d belch a cutting acid belch and in my moment of dyspepsia have deep self-illuminating thoughts. I learned to shrug off these moments of insight. The road to addiction is one of rationalization.

A barbiturate hangover is a terrible thing, and after drugging myself with 600 milligrams of secobarbital I came awake next morning with a hell of a one. My eyelids would be heavy, breakfast had no taste, voices and images came at me from a great distance. My hands were coated by thick gloves. My body belonged to someone else. My inhibitions were gone; I was grumpy and argumentative. What friends I had gave me funny looks. Some mornings I was “sick” and didn’t go to work at all. I had lost my zeal for life, and would lie like a wounded hero on the davenport and beg my wife to come wait on me. She saw what was happening to me, what was happening to us, but it was a measure of my dependency on drugs that I would not let her help me.

I grew to hate myself.

Using as many sleeping pills as I used the year before I left for Viet Nam required a source of supply. I never stole them; I didn’t have to. I ordered them by the bottle from a drug company that sent fliers to physicians. The drug supply house also carried sundries, so to show them that drugs weren’t my only interest I’d order two tubes of Crest toothpaste, a bottle of aspirin, a roll of dental floss—and one thousand Seconal. I had the boxes containing the Crest, the aspirin, the dental floss, and the Seconal shipped to my mailbox at medical school. Getting the pills into the house past my wife was the hardest part, but that was no task for one becoming accomplished in the art of legerdemain. I was so secretive that I could carry a night’s dosage of pills into the bathroom tucked under the waistband of my shorts and remove and pop them in the bat of an eye, even while my unknowing wife sat reading a book in the tub three feet away.

A drug habit is like smoking or overeating. Soon the main preoccupation is not how much fun it is, but how to get rid of it. Viet Nam was my answer. What awaited me there was a hasty resolution to my problem: if I did survive the year, one way or another I’d come home with the monkey off my back.

Six weeks out of internal medicine residency I found myself on a plane for Viet Nam. Majestic cumulus clouds stretched out between the 707 and the Pacific but my thoughts were on matters closer to earth. I had in my suitcase one bottle of barbiturates, and when they were gone that was it, over, finished. Someone across the aisle pulled out a copy of Valley of the Dolls. I did not ask to read it.

On Thanksgiving day, 1967, groggy as I was, I tried to listen to the annual University of Texas and Texas A&M game. It didn’t matter that I was nauseated and hadn’t eaten for two days, or that maggots and other insects roiled across the ceiling in such numbers that I was afraid they would soon spill off and fill the bed with the stink of their leavings. It didn’t matter that I was 10,000 miles from College Station or that my hootch was so near the flight line I could barely hear the radio for the drone, then roar, then whistle, then pop, of the F-4 Phantom jets as they screamed into the sky on combat missions. It didn’t matter that the broadcast over Armed Forces Radio was delayed, and that the game had already been played. What mattered was that I was the number-one Texas rooter of all time, and would give my yells to an empty room if necessary. At the very least, I had to find out who won.

I was destined to miss it. At the half, A&M led by a score of 3–0. I got out of bed, pulled on some pants, opened the door of the hootch to the bright clouds of midday, and fell to the sand after emitting what they later told me was the screech of a banshee. I had chosen cold turkey for Thanksgiving, and what it got me was an unexpected grand mal convulsion.

I woke up in the emergency room of the 12th USAF Hospital, Cam Ranh Bay, Republic of Viet Nam, where I was assigned as a staff internist. My rank was Captain, Medical Corps. My serial number was FV3166651. I woke up and cried in pain, because the nurse was shooting something into my arm. The monsoon rain on the tin roof of the infirmary sounded like a gravel truck skidding over a rock quarry. The Lysol smell of the emergency room was nothing compared to the packet of ammonia smelling salts someone had placed on my upper lip. My back was on fire, my vision was blurred and I felt like I had been smeared on an end run.

“John,” the man kept saying, peering at me out of the shadows, “you had a convulsion. Yes, a grand mal. We brought you to the emergency room.” He was the leader of a group of six holding me down. He was my chief of medicine, my boss, Major Monte Miller. “Have you been taking anything?” he wanted to know.

He would have to ask that.

My first thought a few moments earlier had been Now you’ll never get to be President of the United States. My second thought had been Now it’ll all come out. My third thought was the only one I was willing to verbalize. “Who,” I asked through puffy lips, “won the A&M game?”

“The Aggies,” someone said.

My spirits dropped to new lows.

“But you’re a doctor, John,” the chief of medicine told me when I spilled my story about the sleeping pills and how I had stopped taking them when my supply ran out. “Didn’t you know that a convulsion could have killed you? The mortality rate for withdrawal convulsion from barbiturates must be twenty-five, thirty per cent. Didn’t you think about that?” I shook my head. I had not. It was a measure of my degree of rationalization that I thought I could quit and get off scot-free.

Miller examined me, ordered weaning doses of secobarbital to be given during my hospital stay, then left. That first night, the monsoon rain still drumming down, was the worst. The elaborate wall of self-deception I had built around my life had fallen; I had lived with a lie and now that it was gone I felt naked. The next day a psychiatrist came, and he had to step gingerly to avoid the puddles of water that had flowed under the door from the storm’s runoff.

“As far as I’m concerned,” the psychiatrist said after hearing my story, “you’re just another doctor with a drug problem. What matters is what happens a month or a year or five years from now. You’ll have to watch it the rest of your life. And John, before you ever reach for another pill you had better think long and hard about what you’re getting yourself into. See you.”

You’re just another doctor with a drug problem.

The words stung, and the more they came back to me the more they stung. I had never considered myself just another anything, but I concluded that the shrink was right. Big as my problem was to me, it was only my personal experience of something that happens all the time. How many doctors get hooked? Quite a few. One reason is that, like me, doctors grow so used to solving problems by giving pills that to use these same methods on themselves seems not only reasonable but desirable. Stopping the pills and convulsing were only the beginning of recovery. Waiting for me after I returned from Viet Nam was a year of duty treating military dependents at an air base in California. It was the hardest year of my life. I spent many sleepless nights, nights when, if they had been available, I probably would have taken sleeping pills. I didn’t. In time I learned that for every bad night there follows a good one, and that sleep is a habit that can be cultivated by one who will make the effort. And I came to realize that even if pills can take you to nirvana, the world is always waiting for you when you get back.

Five years ago, two years and three jobs after I left the military, I decided that medical practice was not for me. We moved to Austin, where I have been able to teach part-time, write, and do medical editing. My wife has gone back to teaching school, and we share the housework and child rearing. I can make a passable meat loaf, and my slowly simmered pinto beans are the family’s favorite dish. I hang out the clothes, jog, dole out lunch money to the kids, and have supper going by the time my hungry wife gets home from work. It is a selfish existence when one considers that I could be on the line seeing sick patients, but for me it is not only the right thing, it is the only thing to be doing.

I don’t take pills any more, but I’ll never forget the personal hell that using them brought me. The process of recovery has been a long one, and part of it has been a search and destroy mission through my past. “Where you going for your workup?” a flight surgeon asked me not long after the convulsion. He thought that the cause of my seizure was unknown and that a lengthy neurologic workup would be necessary. There would be no workup, but to tell him this I would have had to explain my addiction and withdrawal. Instead I answered vaguely and kept my secret. Nor have I told others, at least not many.

I had almost forgotten something Monte Miller said the day in late November 1967 when I checked out of the hospital and walked with him around to the medicine ward, Quonset 8, where I would be resuming my duties as an Air Force physician. Miller was an overgrown boy in his late thirties, tall, balding, from Missouri. He seemed to sense my need for encouragement, for something that would sum up what had happened. We paused on the sidewalk outside the door to the ward, and my boss looked at me and grinned. He said, “John, some docs get so strung out on pills they never get off. But you had a convulsion and it shook the hell out of you. All things considered, it may just be the best thing that ever happened to you.”

I nodded, not then fully able to comprehend the truth of what he said. Then Miller opened the door and we went inside and started making rounds.

John Deaton is a freelance medical writer and editor who lives in Austin.

- More About:

- Health

- TM Classics

- Medicine

- Longreads

- Austin