Houstonians like to tell you how far they’ve come. It is part and parcel of living in dreamland, where money flows and wishes often come true. You can hear these stories again and again and still be surprised at the distances people traved—not physical distances so much as psychological, emotional, philosophical distances that elude measurement and leave people simply shaking their heads. “My daddy,” someone might say, or “When I was a youngster,” and thus begins another flabbergasting tale of origins in the oil field grit, or in the mill towns of the Piney Woods, or in some godforsaken dust bowl or backwater swamp where dead-end jobs and frustrated ambitions have driven people to pack up and move to Houston. It is a way people have of accounting for themselves, of trying to explain to you the wonder of it all. “Look at me now!” they are saying, and why shouldn’t they say it, for that is the elemental purpose of the city in the lives of most Houstonians: to go far.

If you spend any time on MacGregor Way you will hear these stories in particular abundance, for this street, and the shaded neighborhood that embraces it, occupy an extraordinary place in the minds of the people who live there. With its broad central boulevards and bravura mansions, MacGregor recalls—in quite deliberate fashion—the shoulder-to-shoulder palaces of River Oaks. And just as River Oaks signifies a state of mind as much as a community, so does MacGregor Way represent a larger notion than an accumulation of people with similar lifestyles and standards of living. It is the center of the black moneyed elite, one of the wealthiest minority neighborhoods in the country. For blacks in Houston, MacGregor Way is part of an economic phenomenon as important in its way as the cultural renaissance in Harlem in the twenties, or the black political and social efflorescence of modern Atlanta. To be rich and powerful, and black, is to belong to an America that black people have seen, if at all, only through the kitchen door.

Until recently the concerns of the residents of MacGregor Way have been the concerns of wealthy and exclusive people everywhere. Money to spend brings an interest in quality, which translates into German cars and French wines, pedigreed dogs, copies of Architectural Digest on the coffee table, and Albert Nipon dresses on the cool and elegant ladies who breeze through the living rooms, chatting authoritatively about Houston drivers versus Roman drivers or where to get the best cuts of meat or the relative merits of hair stylists. You might engage their husbands in thoroughgoing discussions about interest rates or the restoration of vintage cars. The people of MacGregor Way regard education with old-fashioned reverence and spare no expense in sending their children to the best private schools, having them tutored in music and languages and English riding, and packing them off to Israel for a “learning experience.” When they talk about problems in their neighborhood they are usually talking about property crime. Most residents live behind barred windows with expensive security systems. There is a strong impulse, typical of rich neighborhoods, to shut out the problems of the less fortunate and to concentrate on one’s own environment. Indeed, MacGregor Way has a reputation in the larger black community, like River Oaks among whites, as a place where people look out for themselves. The epithet Nigger Oaks has currency not only among white racists but also among the poorer blacks in the city, who suspect parvenu blacks of having more allegiance to their class than to their race.

The residents of MacGregor Way, however, regard themselves simply as people who have come far. Here the judges, the doctors, the tycoons, and the sports stars have established a kind of homeland for blacks who have made it. In many cases they are the sons and daughters of the maids and yardmen who attended these homes when MacGregor Way was a wealthy white neighborhood, and for them, living on MacGregor Way is more than having a nice house in a pretty neighborhood; it is the tangible fulfillment of their childhood fantasies. “When you’ve got a home in this neighborhood you just don’t think about moving anywhere else,” says Velma Jones, the daughter of one of those maids. “Instead you begin to think about a house in the country, or perhaps a yacht. Someplace to get away to, in other words.”

The neighborhood is bounded on the west and east by Hermann and MacGregor parks, on the north by Southmore Street, and on the south by Old Spanish Trail. Brays Bayou, a channelized and charmless stream, wends through the center of the neighborhood, separating the parallel boulevards of North and South MacGregor. In the morning, before the dew has burned off, you can see joggers circulating on the trail that runs along the bayou. The neighborhood is only an instant from downtown, and within walking distance of the enormous institutions where many residents of MacGregor Way work, such as the University of Houston, Texas Southern University, and the vast Texas Medical Center. “It’s not a perfect community by any means,” says Carolyn Hall, wife of city councilman Anthony Hall, “but it is a place where we treasure our surroundings. It’s a nice place to live and a good place for our children to grow up. That’s why we were all so alarmed when we heard the news this spring.”

Human Problems

The news was that Harris County, in conjunction with the State of Texas, was planning to erect a psychiatric hospital on seven acres of land on the western edge of South MacGregor Way. The land would be donated by the Texas Medical Center, which already had constructed a day care center for its employees near the site. Next door is the High School for Health Professions, a magnet school that draws students from all over Houston.

Although Houston is world famous for its private hospitals, which are loosely allied in the Texas Medical Center, its reputation for maintaining public facilities is considerably different—in the past, the subject of scandal. The psychiatric ward of Jefferson Davis Hospital is still described in public hearings as a snake pit, and certainly no official of the county would boast that the needs of his indigent constituents who happen to be insane, retarded, or emotionally disturbed are being adequately served. The reason they are not is that this particular constituency is so woefully powerless as to be a political nullity—or worse. After all, who wants a psychiatric hospital in his neighborhood? That’s a question many a politician has asked himself in Houston, and the answer is: no one who can vote.

Even before the hospital issue arose, the residents of MacGregor Way were already feeling threatened by their formidable institutional neighbors. The University of Houston, which stretches thirty blocks from the Gulf Freeway to North MacGregor, is aggressively buying more land. The venerable Texas Southern University, where so many blacks in the neighborhood went to school, has used its power of eminent domain to condemn houses on nearby Blodgett Street. The county has acquired a nursing home in the area that it plans to convert into a community hospital, complete with a small psychiatric ward. And recently the Black Muslims leased a down-at-the-heels motel on North MacGregor, which they have converted into a halfway house for ex-convicts.

That the proposed psychiatric hospital also came to be located on MacGregor Way has raised the predictable charge of racism; after all, as nearly everyone in the neighborhood points out, this would never happen in River Oaks. And yet that charge has as much to do with class as it does with race, for it is the upper crust of white society to which the people in MacGregor instinctively compare themselves. Indeed, the hospital controversy has caused many of the neighbors to pause and consider who they are and how far they’ve traveled. While there is scarcely anyone in the MacGregor area who does not identify with the needs of the underprivileged, and in some sentimental way feel himself a part of the vast underclass to which the majority of black people still belong, it is this very underclass that the new hospital would serve. Now the neighbors in MacGregor find themselves in the same dilemma that faces wealthy people everywhere: by protecting the interests of their class they have become the enemies of the poor.

In Houston, the poor have very few friends. For twenty years there has been a recognized need for a new psychiatric hospital, and with all the booming growth in Harris County, existing public facilities have begun to compete for space. It is rather like five people attempting to sit on a bench that accommodates four. The squeeze first became apparent in the emergency room of Ben Taub Hospital, which last year handled 96,000 cases, one of the largest caseloads of any such facility in the Southwest. A shortage of beds was pushing emergency room patients into the hallway, reviving memories of the scandals of the past. Ben Taub’s administrators began casting covetous eyes downward, to the basement, where the county morgue is located—itself so overcrowded that the county medical examiner had to take offices in another building. The morgue is also the source of the persistent stench that characterizes Ben Taub. If there is one constituency with less influence than the indigent insane of the county, it is the unclaimed dead. They were, in other words, the first to be pushed off the county bench.

At the same time, prospective mothers were stacking up in the hallways of Jeff Davis Hospital, which lays claim to being the nation’s busiest maternity center; this year it will deliver more than 15,000 new Houstonians. The hospital board decided to expand the obstetric ward to the ninth, tenth, and eleventh floors, where the insane then resided.

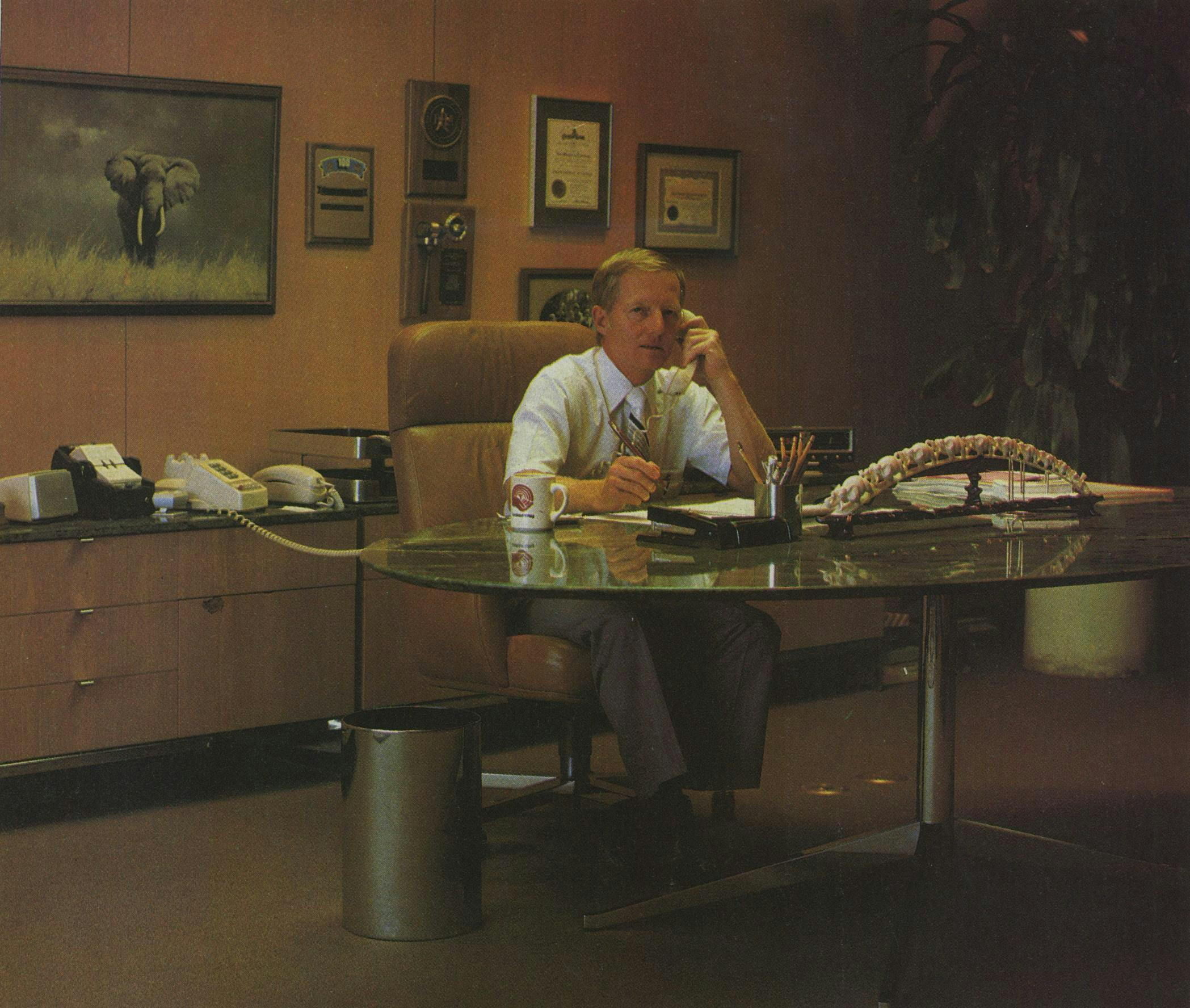

The unwelcome task of finding new homes for the morgue and the psychiatric ward fell to county judge Jon Lindsay, a brisk blond man in his second term as the first Republican judge in Harris County government. Lindsay is a civil engineer by training, and he has the engineer’s trait of seeing all problems as design problems, rather than as immensely complicated human problems that must be thrashed out and awkwardly compromised. It was precisely this trait that made him the perfect man for the job, although as a white Republican he could expect little gain from championing the needs of the poor. With a limited amount of bond money and some innovative financing, the judge acquired the Center Pavilion Hospital, an antiquated and rather poorly constructed building that would provide the minimum amount of space needed to get the insane out of Jeff Davis and the bodies out of Ben Taub. “It was never meant to be something we’d really be proud of,’’ Lindsay admits, but it did solve problems, and from an engineer’s point of view it was a delight. The judge had designed a bigger bench.

“That’s when the Texas Medical Center discovered that we were going to put the morgue a block down the street from M. D. Anderson,” recalls Lindsay. The M. D. Anderson Hospital and Tumor Institute, the flagship of the Texas Medical Center, is a world-renowned cancer hospital serving an international community. Although the Medical Center is a benevolent organization, it is also a sophisticated and terrifically powerful political lobbying group, with the most influential boardroom in Houston and emotional ties to every Texas family that has passed through any of its 27 health institutions. “I had a group in here every two or three days putting pressure on me,” says Lindsay. “We had some raw times.”

What the judge heard was that cancer patients would be demoralized when they glanced out their windows at M. D. Anderson and saw hearses ferrying their cargo from the building down the street. It was an aesthetic qualm the judge had little patience for; besides, he had already taken it into account: “We designed the morgue so that the bodies would come around on the back side and go up private elevators.” The Medical Center representatives weren’t impressed. Judge Lindsay was impressed that they weren’t impressed. He is a firm man with a thin line for a smile and cool blue eyes that suggest judicial impartiality and personal remoteness. At the same time, he enjoys the reputation of being the fair-haired boy of the Republican party, a favorite if not a protégé of the governor’s, a man, in short, who has come far and expects to go a lot farther. To some extent, that ambition could be encouraged or defeated by the Texas Medical Center. It is certainly the last enemy any politician in Houston wants to make.

Judge Lindsay requested a meeting of the interested parties, and in October 1980 he found himself in the conference room of the Fannin Bank, one of those lavish corporate rooms with a view of Houston that can make you gulp. Facing some “high-powered honchos,” as he calls them, the judge admitted he was willing to compromise. That was the politician speaking. The engineer added: but you’ll have to find me a better solution.

The better solution was more than either the politician or the engineer could have hoped for. Within 45 days the high-powered honchos returned with a plan that included two tracts of land donated by the Medical Center—one for the morgue and one for a new psychiatric hospital—and the promise of legislative support to acquire state funding for the hospital. It would be first-class. Instead of the 60 beds that Center Pavilion could accommodate, the new hospital would have 250 beds and room to expand. It would be close to the Medical Center, so that Baylor and University of Texas doctors could use it as a teaching facility. What’s more, it would be located in a nice, quiet neighborhood, one that the judge knew well. He lived in MacGregor himself until 1970, a block away from the proposed site. Like most white people in the neighborhood, he moved away when his block turned black.

A Rent Man

James Donatto is sitting in the Wunderbar drinking Tanqueray and tonic. He comes here nearly every afternoon during happy hour to socialize with his neighbors. The Wunderbar is a dark and stylish club patronized by upscale black lawyers and silk-suited businessmen; it is one of the most fashionable spots in Houston in the dwindling hours before dinnertime. Here Donatto is unrepentantly out of place in his guayabera, double-knit trousers, and cowboy boots. At 37, with a curly black fringe of beard and a high, gleaming forehead, he resembles in his serious moments Holbein’s portrait of Henry VIII, with a sepia overlay. In the Wunderbar, however, he looks more like a freewheeling Negro version of Wolfman Jack. He loves being here, being close to the glamorous crowd, even if he doesn’t entirely feel a part of it. “It’s a great time to be in Houston,” he exults. “I’m really eating high on the hog.”

To his great surprise, Donatto has been elected chairperson of the neighborhood task force to fight the placement of the hospital on MacGregor Way. “I am in awe,” he confesses, “of all these persons I’m chairperson over. Teachers! Educators! Professional people! I’m the only person in the group without a college degree.”

James Donatto has come far, but he still harbors a sneaking sense that he got into MacGregor more by luck and pluck than by intellectual merit. He made his money in apartment houses. “I know I’m not part of an elite. I’m a rent man. I collect the rent on Friday and Saturday nights. I split verbs, I say ‘fo’ instead of ‘for.’ I’m a regular kind of fella. Maybe I don’t have three or four initials after my name, but I feel a sense of accomplishment when I turn into my driveway. I feel good about the kind of start I’m giving my son and daughter. It’s a long way from where I came from—a two-bedroom shack on a dirt road in Liberty, Texas. My father built that house on the settlement he got when he lost his thumb in a construction accident.”

Donatto lives now in a large brick house once owned by former Watergate prosecutor Leon Jaworski, who is the head of the Medical Center board. This fact excites Donatto; he’s a history buff, and he has traced his plot of land back to the original grant by Stephen F. Austin to Henry Tierwester in 1836. Like many Houstonians, Donatto has ties to the Medical Center, which may not be as deep and impressive as Jaworski’s but are nonetheless profoundly important in his life. He was an orderly at Methodist Hospital in his student days, and he witnessed firsthand some of the miracles performed there. Now Donatto’s son has sickle-cell anemia and is receiving treatment at St. Luke’s Episcopal Hospital. It is a comfort to know that the best medical care in the nation is only a few blocks from his doorstep.

“When I first got involved in this,” Donatto says, “my wife questioned me. ‘Jimmy, that’s not like you to be opposing a hospital,’ she said. To be honest, I questioned myself.” This issue has made him take stock of himself. Who is James Donatto? He is a sentimental man. In his home he has stored a bottle of port, vintage 1963, the year he graduated from high school, and he plans to drink it on the twentieth anniversary of that event: a toast to himself. But he has already discovered that the James Donatto approaching 1983 is a more complex creature than the Creole country boy who couldn’t wait to escape the dirt roads of Liberty. “I thought at one time you couldn’t be black and conservative,” he says; now he finds that President Reagan makes sense to him. He has become a pillar of his community, an outspoken proponent of property rights. “We owe it to ourselves,” he says. “Other folks have enjoyed these fruits for years. Now that we’ve finally arrived, we find that we’re just as vulnerable as anyone else.” He means to protect the material interests of his family and the real estate values of his neighborhood. “If I’m going to be in the neighborhood thirty years from now, I have to be concerned about what is happening to it today.”

And yet he is troubled by the thought that he may have come too far, in some respects, from the person he used to be. That person was a student firebrand who spoke out for the needs of the poor and the minorities. What would he think about the James Donatto of today? Driving around in his Mercedes to pick up the rent? Fighting the county over a public health facility?

Donatto points out that he is opposing not the hospital but rather its placement in his neighborhood. But the very fact of his opposition, and that of his neighbors, has already stalled construction of the hospital and may put it off for years to come. The anxiety that people in MacGregor feel is as nothing compared with the genuine suffering of people who need the public facilities, and that suffering is being prolonged and aggravated by the resistance of the neighborhood. None of this is lost on Donatto. Like most blacks of his generation, he has lived under the injunction to “do well and do good,” and now that he has done well for himself, he doesn’t like to think that he is standing in the way of the poor and defenseless who will constitute the clientele of the new hospital.

Over another gin and tonic an elegant young lawyer named Carl reassures him. “I’ve got some experience in these matters,” he tells Donatto. “I used to work in a mental hospital. There’s one thing about the insane that you just can’t change.”

“What’s that?”

“They wander.”

“There it is Again”

Carolyn Hall remembers being appalled at the thought that dangerous people would be placed in her neighborhood, “people who could harm my children.” She is a vivacious woman with large and quite expressive eyes that, when she is properly provoked, will suddenly dissolve into tears. “I’m a terrible crybaby,” she admits. “That’s why they always show me on television. Because of my reaction.”

Carolyn grew up in the Trinity Gardens area of Northeast Houston, where her parents operated a grocery store next to their house. It was a family enterprise; the children worked in the store before they went to school in the morning, and in the afternoon they delivered groceries. They worked hard. They prospered. Later Carolyn’s father opened up a gas station next to the grocery, and the children worked there as well. Carolyn remembers that on her first date with Anthony Hall, whom she would marry, he had to wait until she had finished washing cars at the station.

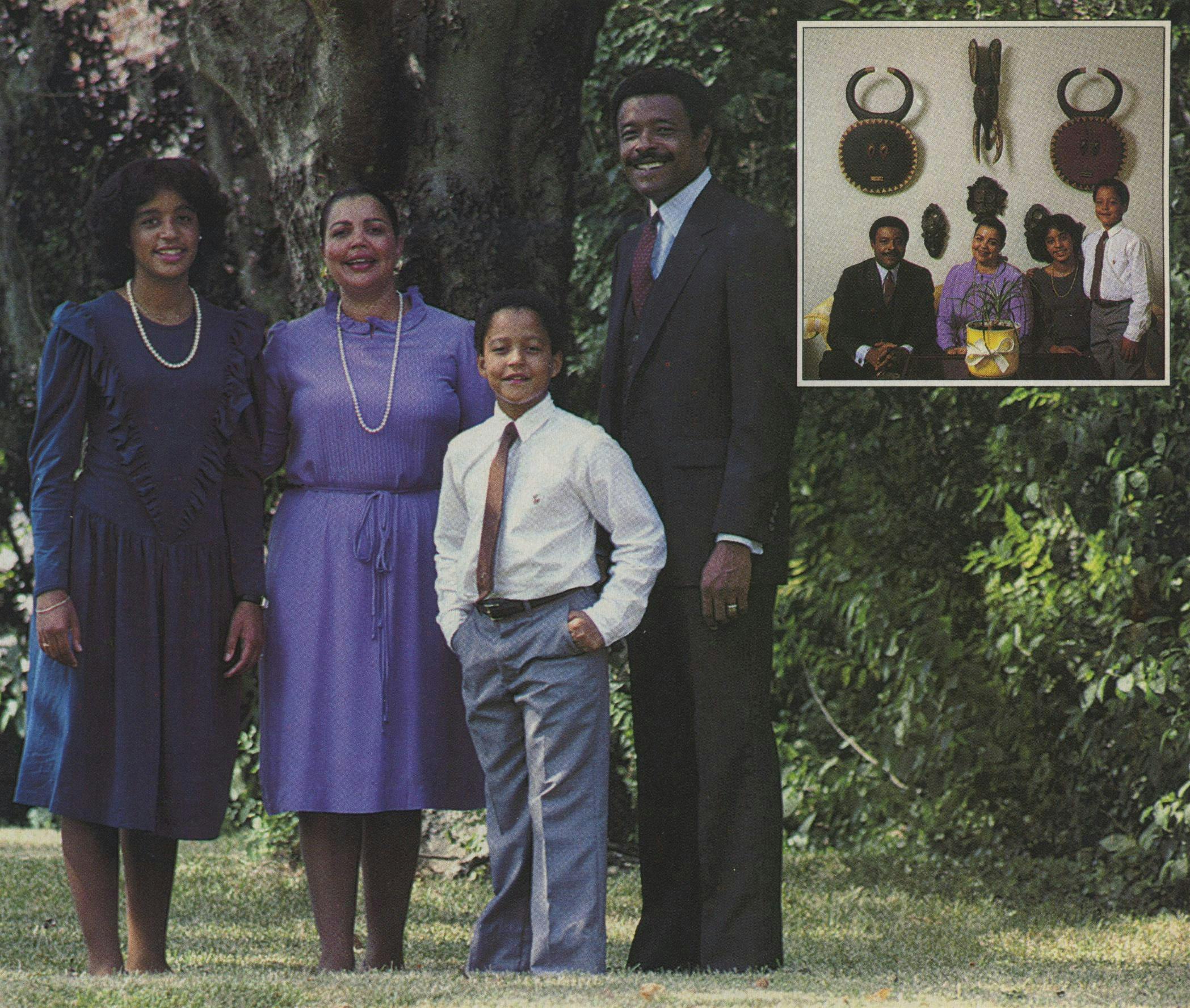

Anthony Hall’s mother was a schoolteacher; his stepfather was a porter at the Suniland Furniture Company. Anthony graduated from Jack Yates High School in the Third Ward, and when he met Carolyn he was on his way to Howard University in Washington, D.C., on an academic scholarship. In 1965 he married Carolyn and received a commission in the U.S. Army, and they spent the first years of their marriage in Germany. In 1968 Anthony found himself in Viet Nam, while Carolyn was teaching school back in Houston, and that year a red brick house with columns came up for sale on Rio Vista, in the South MacGregor area. Carolyn could remember riding through this area as a child: “Those were the most beautiful homes, with the big-beam magnolia trees out front and lawns with four-inch grass.” It was everything she wanted.

Now their home is furnished with Queen Anne armchairs and Chippendale tables; African masks decorate the walls, Anthony Hall is, like Jon Lindsay, a bright political commodity: a city councilman, an attorney, a former state representative, with a brilliant smile and a handsome manner that give promise of more to come.

Despite Anthony Hall’s political connections, it was more than a year after the meeting between Judge Lindsay and the high-powered honchos in the Fannin Bank building that Anthony and other people in the neighborhood became aware of the plans to put the hospital there. No one had bothered to tell them. In that time the Legislature had appropriated the money and the county was moving ahead as if the hospital were a fait accompli. When people in the neighborhood finally learned what was happening, they felt ignored and abused. “I want to think it’s not because we’re black,” says Carolyn. “I want to think we’ve moved beyond that. But every now and then that ol’ ugly head pops up and you say, ‘There it is again.’ ”

South of Blodgett

MacGregor Way has always been a monument to discrimination. It was developed in the thirties by Jews who were barred from River Oaks. Here, along the banks of Brays Bayou, the great mercantile fortunes of the Weingartens, the Fingers, the Battelsteins, and the Sakowitzes would repose.

But not for long. MacGregor Way borders the section of Houston known as the Third Ward, which was opened to black settlement around the time MacGregor was developed and was filled to bursting with indigent and laboring-class blacks by the end of World War II. Wheeler Avenue was the main drag, and Blodgett Street was the dividing line between the black Third Ward and the white neighborhoods to the south.

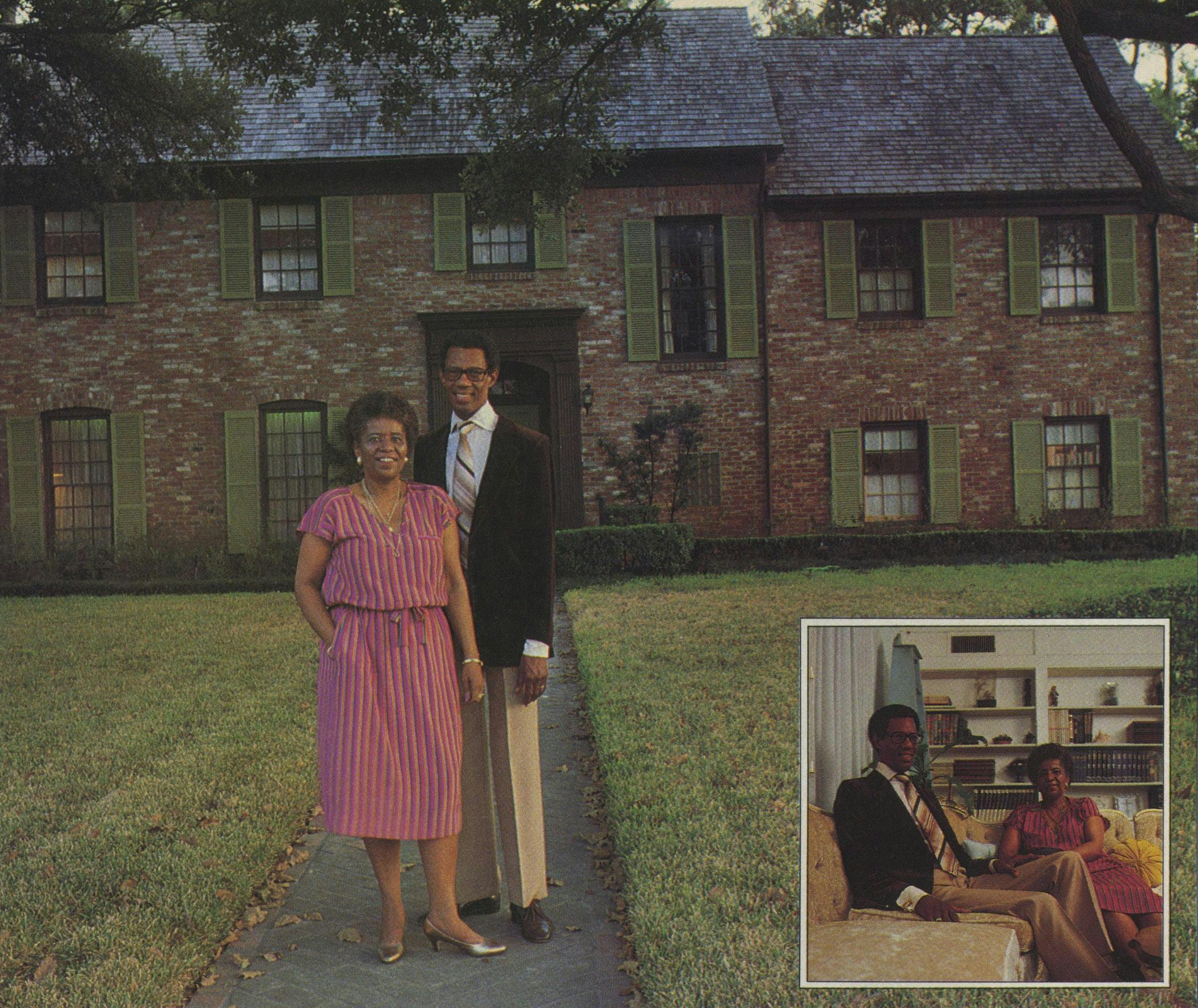

Alex and Ethlyne Tillman were living on Dowling Street during the war, in a single room that they rented from a woman with five children. Alex was a broad-shouldered farm boy with a long face and a quick smile. He had met Ethlyne at the city coliseum. “Ella Fitzgerald was singing,” he recalls. “I went up to Ethlyne and asked her to dance. That was in 1942. Ella Fitzgerald was in her prime.”

“So were you,” Ethlyne remembers.

They married and moved to Dowling Street, next door to a nightclub, where the wartime music kept them awake till all hours. The sounds then were Billie Holiday and Cab Calloway, and at two in the morning the jukebox might as well have been in the same room with Alex and Ethlyne.

“I’ll be sooo glad when my man comes home …”

They had grown up poor and they wanted better. Ethlyne became a public school teacher, while Alex went to work as a blacksmith and machinist for the Southern Pacific Railroad. On weekends he moonlighted as a longshoreman at the Port of Houston. He would leave the house at seven Friday evening and work straight through until Monday morning. Ethlyne would have breakfast waiting. An hour after his shower, Alex would be back at work at Southern Pacific. On his broad shoulders and tireless constitution the Tillman family began to advance.

They bought a government house that was too small when their first child was born and became impossible when their second came. Housing for blacks in the early fifties was in a state of crisis. The wards could no longer contain them. When a Negro cattleman named Jack Caesar became the first of his race to move south of Blodgett, his house was promptly bombed.

In many ways the Tillmans’ story is the opposite of the ugly episodes that have characterized the transition of urban neighborhoods from white to black. They bought a house on Rosewood, an all-white street. Their family doctor, who was Jewish, helped them finance their home, and the day they moved in, their neighbor brought them a platter of pastries. It was secure and peaceful then; their neighbors watched out for them, and they took care of each other’s children.

Then the panic came. Blacks began moving south of Blodgett in great numbers, aided by predatory real estate agents and by the city newspapers, which began listing all property for sale in the white, largely Jewish neighborhood between Blodgett and North MacGregor in their “colored” columns. It was common in the fifties to see yard signs proclaiming, “This Is Our Home, It’s Not for Sale”—words that would be swallowed, in almost every case, as white owners stampeded and property values collapsed. Three-story houses were selling for less than $20,000. The Tillmans took advantage of the bargain. They bought an immense white house on North MacGregor Way with a circular drive and a yard filled with loblolly pines.

Soon after that, Alex’s health began to fail. He had always worked too hard, but it was not that. There had been a time when he could play basketball all day long; suddenly, the slightest effort winded him. It wasn’t until years later that he made the connection between the fibrosis they found in his lungs and the asbestos he had been unloading from the holds of ships, which had filled the air like a snowstorm and left him looking, as he recalls, “like a white mop.”

Now he receives treatment in the Texas Medical Center. “They do me a good service,” he warrants.

The Chicken-Eaters

By 1960 Brays Bayou was the dividing line between the races, and whites were determined to hold off the advance. But when a small brick house in the 3100 block of South MacGregor went to foreclosure, it was purchased at auction by a black biology professor. The white population took wing. In a single decade the South MacGregor area changed from a completely white enclave to one that was predominantly black.

During the transition the typical couple moving to MacGregor Way was made up of a postal worker and a teacher: they were not wealthy, in other words, but they had reliable incomes, and they were picking up the MacGregor mansions at preposterously low prices. In many cases the utility bills were higher than the house payments. But there were other prices to pay. The house of a prominent black minister was burned down. People were harassed on the street and in their homes. Some outraged whites actually tore down their homes rather than sell to blacks; some of those lots are still vacant today, like missing boards in a picket fence. Joe Russell, a white realtor who has lived in the MacGregor area since 1948, remembers the first black couple he represented in South MacGregor. The wife was a teacher and the husband a union worker. They bought a handsome stone house on the corner of Fernwood and Kuhlman. “These people were terrorized,” Russell says. “I mean broken windows, gunshots into the house, threats on the telephone—they ended up stringing gold-toned chicken wire across their windows. It was terrible. I mean sheer terror. It took real courage for black people to come into this area.”

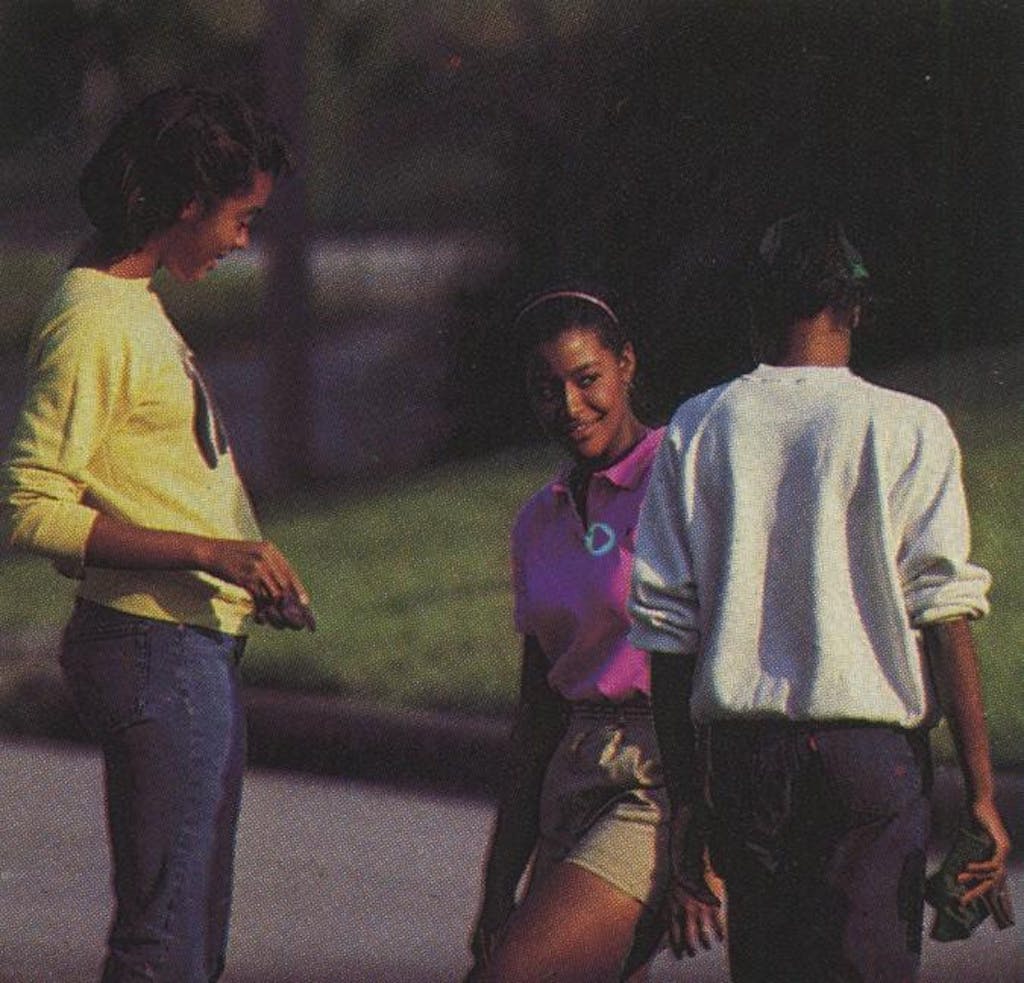

In the seventies the lives of black people—at least, of some black people—began to change for the better, and this change was reflected in MacGregor. Real estate values skyrocketed, corresponding to the demand among affluent black professionals who wanted into the area. It was this second wave of black immigrants who brought the real wealth to the neighborhood. They were the moneyed blacks, the doctors who made clever investments, the attorneys with fabulous fees. The word had gone out that Houston, which has never enjoyed a reputation for being racially progressive and which remains one of the most segregated cities in the country, was nonetheless the place to be if you were black and skilled and wanted to make money. After a while the For Sale signs in MacGregor simply disappeared. Now when a house comes on the market it is frequently sold overnight, to someone on the realtors’ long lists of buyers clamoring to get in. Many of those potential buyers are white.

That has many people in MacGregor worried. Indeed, some of the new residents are as jealous of their ground as the whites who preceded them; there is even talk of “problems” with the whites—for instance, the propensity of white people to “slum up the neighborhood” by crowding too many people into a house. Many of the “better” class of white landowners living in the area are homosexuals who are not troubled by school problems and who feel at ease in a neighborhood where discrimination is a universal problem.

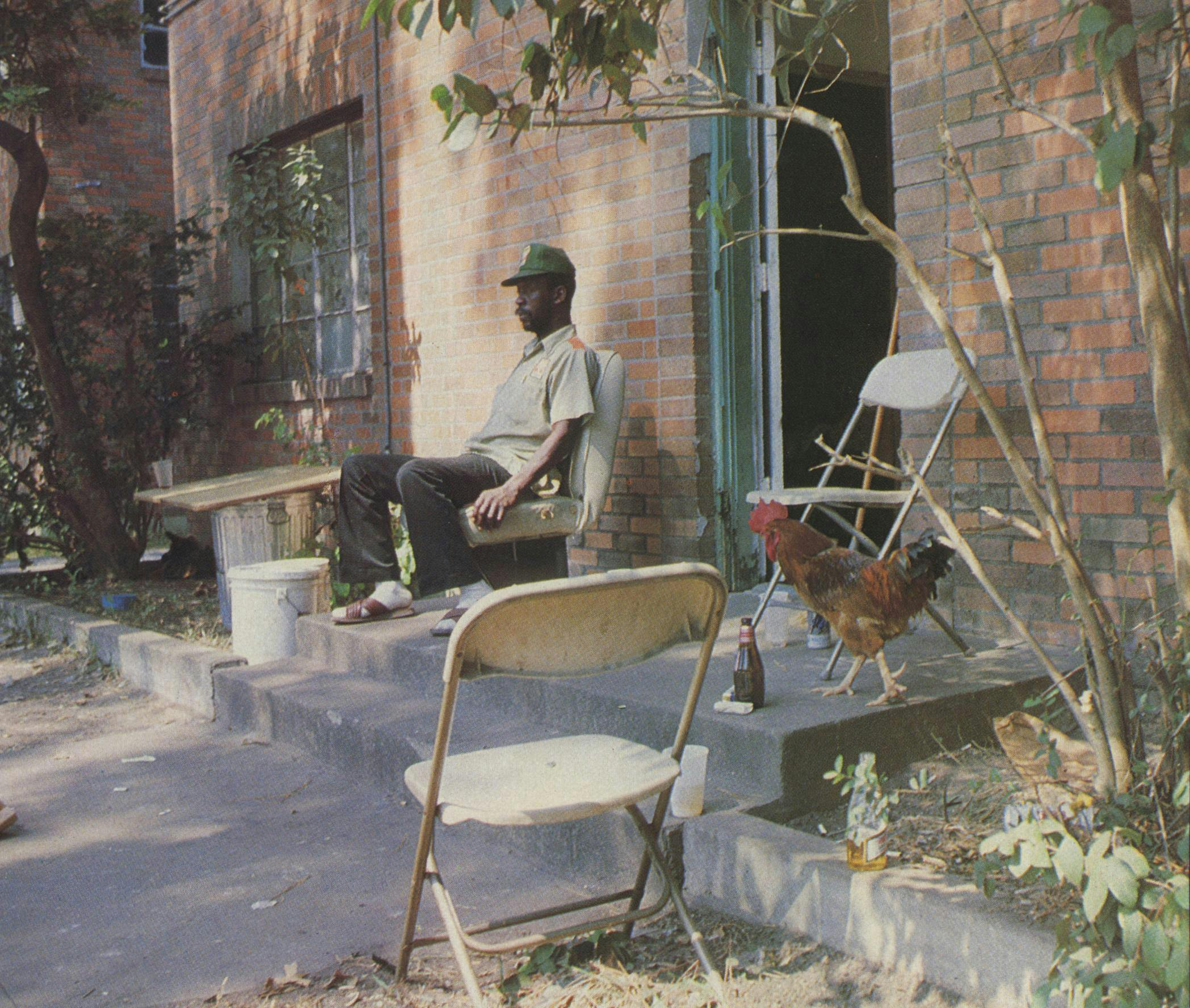

Although there is notoriously no zoning in Houston, neighborhoods can maintain their integrity through deed restrictions, which must be regularly renewed. A sign of a weakened neighborhood is the appearance of apartment houses and drive-in groceries, indicating the erosion of the restrictive covenants. Too often they are followed in dismal procession by cheap bars and gas stations and porno houses until the neighborhood—in the cozy, familial sense of the word—is utterly ruined. One can see the consequences on North MacGregor Way. When Alex and Ethlyne Tillman moved into their big white house they were surrounded by homes of equal stature; now they find themselves bordered by the Tip Top Grocery and facing a block filled with inexpensive apartments. The apartments back onto the bayou, and the grassy bank is covered with the detritus of low-class living. It is hard for the residents of MacGregor to look at the transients in the apartment houses and see themselves but a generation before; instead they see the empty fried chicken boxes in the bayou, the beer cans in the lawns, and, on the stoops of the apartment units, the sullen and unrepentant beer-drinking chicken-eaters whose litter begins at their feet and journeys throughout the neighborhood.

On the other side of the bayou, South MacGregor has always enforced its deed restrictions, and the neighborhood shows it. Except on the western fringe, which is unrestricted, there are no crumbling apartment houses or “sporting lodges.” This is the Ritz. Here is where black people live out the American dream in all its gaudy splendor.

If you begin a tour of South MacGregor Way by crossing the new Highway 288, now under construction, you will approach the High School for Health Professions and the site of the proposed hospital. All of that block is unrestricted. The house closest to the hospital site is a majestic place belonging to a white dentist; next to that is a fraternity house, then a large house for sale at $10.20 a square foot of land, about a quarter of a million dollars.

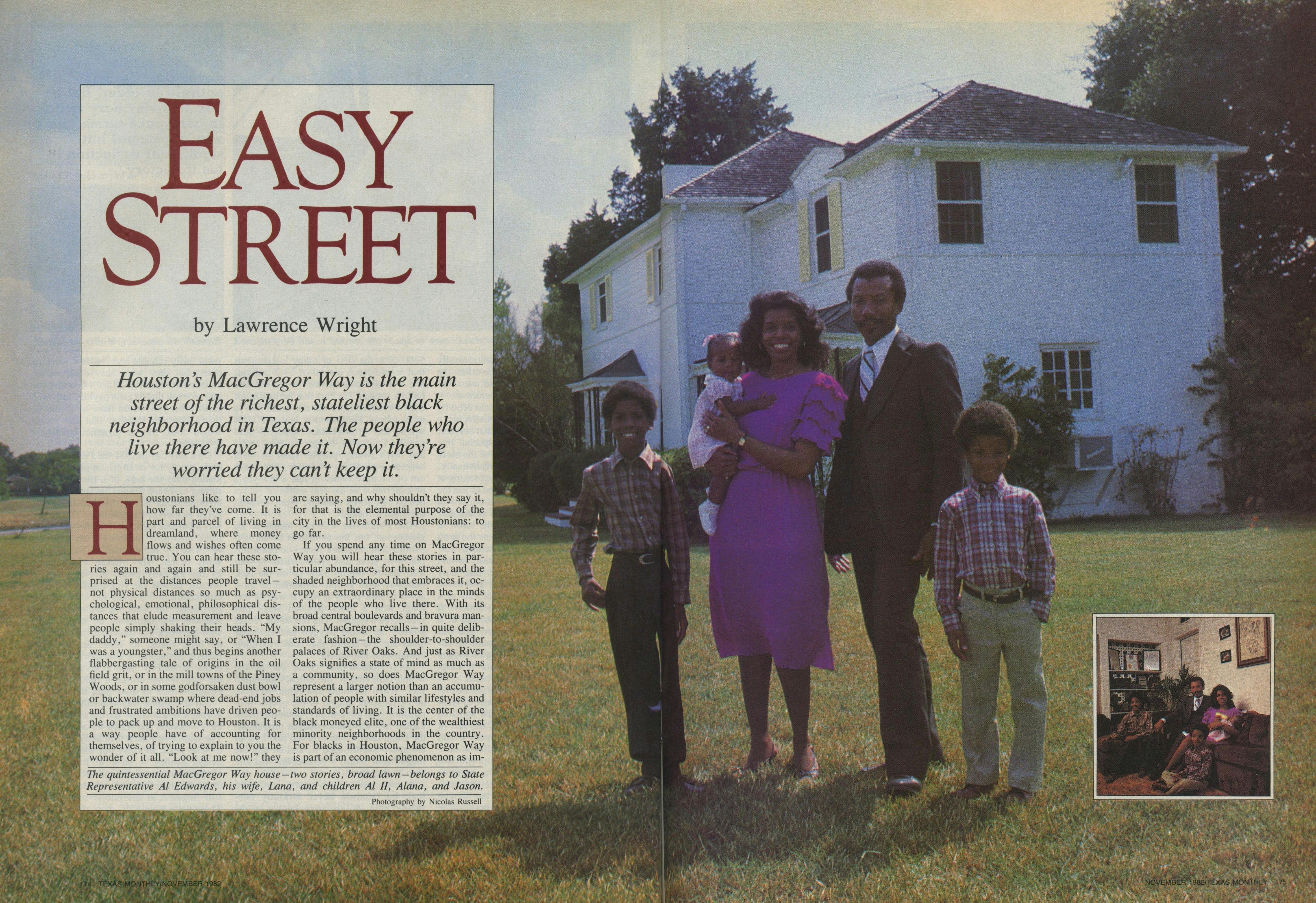

In the next block you will see a large white house belonging to Al Edwards, the state representative of the area, whose home is guarded by a direct descendant of Rin Tin Tin. Edwards’ story is typical of many of his neighbors’: son of a preacher, one of eighteen children, he went to school barefoot and worked his way through Texas Southern University by busing tables at the Houston Club and later by loading hundred-pound sacks of coffee at Maxwell House. “I used to ride down this street just to see these beautiful homes. I always told myself I’d live in a big house someday.” As a member of the Legislature, he voted for the appropriation for the new psychiatric hospital “in or near the Medical Center,” never realizing that could mean within hailing distance of his own home.

Farther down South MacGregor you will pass a handsome house with a circular drive belonging to Tex Harrison, the coach and former player for the Harlem Globetrotters. A brick Tudor in the 3300 block belongs to Leonel Castillo, the former director of the Immigration and Naturalization Service. Nearby lives Lois Adams, whose father acquired the house with a lifetime of tips as the headwaiter of River Oaks Country Club.

In the 3400 block is the home of Al Hopkins. As a boy Hopkins used to walk through this neighborhood on his way to Hermann Park, where he would caddy for 35 cents a game. “You had to have a reason for passing through here or the police would chase you away. This was on the same street where I live now,” he muses. Hopkins owns a drugstore in a poor black section of northern Houston known as Acres Homes. Like all black professionals of his era (he graduated from pharmacy school in 1949), Al Hopkins had to go elsewhere to graduate school, with the State of Texas picking up the tab for tuition and transportation. Recently, the man who couldn’t get his training in Texas completed his second term as president of the State Board of Pharmacy.

The architecture on South MacGregor Way, and on the streets that twine about behind it, such as Parkwood, Roseneath, and Rio Vista, ranges from the high pretension of Tara-like mansions to contemporary brick homes one might find in most neighborhoods of Houston. It is a typical—American jumble of competing aesthetics: a Norman castle of hewn stone next to a Williamsburg colonial next to an insouciant California contemporary.

There is a style of home, especially characteristic of the MacGregor area, known to realtors as Jewish modern, for want of a better term. They are often low-slung, ranch-type affairs with split levels and eccentric architectural features that seem to be inspired by battleship construction. Joe Russell, who has sold a hundred houses of this type, characterizes Jewish modern as “vulgar, ostentatious, with wild colors predominating”—precisely the sort of house, in other words, that white people commonly associate with black people. It is a style more fairly ascribed to the nouveau riche of any race. In front of the houses one can see the accouterments of freshly acquired money in the Winnebagos and sports cars occupying the driveways, like the fanciful carriages of yore.

These are houses that make statements about the people who live in them; they speak of conservative values, of a desire for beauty, of the need to excel, of a lifetime of unremitting and ferocious competitiveness, and overall of the willingness to step forward and announce, “This is who I am.”

And yet it is just at this point—this moment of self-identification—that your average MacGregor resident falters. For it is easy enough to say that you are, for instance, Edith Irby Jones, a highly paid and much-in-demand black doctor with an office filled with community awards and a garage stuffed with Mercedes-Benzes, that you wear diamonds and the governor knows your name: all of that is on display and readily understood by anyone who knows you. But no one can know the memories and dreams that make up your interior life; no one can know that inside Dr. Jones is the little girl who grew up in a three-room house in Hot Springs, Arkansas, with kerosene lamps and no running water, whose earliest memory is the sight of her father stretched out dead on the floor. No one can know what it meant to have the citizens of Hot Springs pass the hat to pay for your first year in medical school at the University of Arkansas, where you were the first black to enter, or the gratitude you felt to the white students who joined you in your legally mandated separate dining room. It is too much to ask who Edith Irby Jones is. You are a blur, Edith Jones.

You might stop at any house on MacGregor and find a similar tale, and it is this common element—the sense of distance traveled—that unites the residents and gives them a feeling of specialness. But it is not just this feeling that makes MacGregor residents so protective of their neighborhood. It is the lack of options, of desirable alternatives. “Living on MacGregor is something we all worked hard to attain,” says Al Hopkins. “But there’s only one MacGregor Way. We still don’t have the mobility white people have. This is it—or disperse. If we had the flexibility we could be more flexible.”

The new hospital, as Judge Lindsay envisions it, would be safe, quiet, attractive, secure—a genuine asset to the neighborhood. But to the people who live in MacGregor it represents the triumph of all the institutional forces that are crushing their fragile community. What’s to stop the universities from moving in, with their power of eminent domain? Already the halfway house is filling up with ex-cons; next year the community hospital on North MacGregor will open its doors. The neighbors see the day when their fine homes will be replaced by dormitories, fraternity houses, hospitals, and parking lots, when the grand boulevards of North and South MacGregor will race with ambulances and the nights will scream with sirens, when their street corners will be patrolled by felons and the alleyways roamed by wandering lunatics and junkie outpatients, when everything that makes MacGregor Way a special place to live will be laid waste by the anonymous urban madness.

Frozen at the Mike

The county commissioners’ court had already held a public meeting on the hospital issue —at which none of the neighbors appeared—but Judge Lindsay listened to the complaints of the MacGregor residents at a separate hearing on July 2, 1982.

The need for the hospital was not difficult to establish. Litrelle Levy, a social worker at Ben Taub who deals with psychiatric patients, introduced herself as “one of those people who’s been telling families we have nothing. Your patient may be very ill at this time, he may have destroyed your home, he may be disturbing your neighbors; the doctors can give him medicine, but you will have to take him home, although he could certainly benefit from, and under ordinary circumstances require, hospitalization. That’s been the role we’ve had to play for several years now.”

Carolyn Hall responded in a wavering voice. She found it difficult to keep her composure in that somber room, with the intrusive lights of the television cameras in her eyes, which were already misting over. “We are not opposed to mental health. We are not opposed to having a facility to treat these people, for we all might become subjects of that illness.” What Carolyn objected to was the contention that the new hospital would not result in an increase in crime in her neighborhood. After all, some of the patients who would be treated in the new hospital would be drug addicts. “I have two kids that I’m raising in that area. I have a daughter, and I would hate to think”—and here Carolyn broke down, and the television cameras zoomed in close—“hate to think that one day on her way from school, some drug addict will attack her and rape her …”

Carolyn saw the placement of the hospital as “a struggle between the haves and the have-nots.” After a lifetime of hard work, she couldn’t imagine herself as a have. She called upon a poem by Langston Hughes to express the emotion she felt, and “how I feel in regards to what’s happening in my community.” The poem is “Mother to Son”:

Well, son, I’ll tell you:

Life for me ain’t been no crystal stair.

It’s had tacks in it,

And splinters,

And boards torn up,

And places with no carpet on the floor—

Bare.

But all the time I’se been a-climbin’ on,

And reachin’ landin’s,

And turnin’ corners.

And sometimes goin’ in the dark

Where there ain’t been no light.

So boy, don’t you turn back.

Don’t you set down on the steps

’Cause you finds it’s kinder hard.

Don’t you fall now—

For I’se still goin’, honey,

I’se still climbin’.

And life for me ain’t been no crystal stair.

Carolyn was followed at the microphone by a fragile young woman named Evelyn Bell, a mental patient. Like Carolyn, she was awed by the occasion, and she began to speak in a quiet, tremulous voice, but instead of stumbling into tears or forging into poetry as Carolyn had done, Evelyn Bell just . . . stopped. She stood frozen at the microphone, trying to get a word out. At first it was merely awkward. “You’re doing fine,” Judge Lindsay assured her, but she was patently not, and everyone knew it. The audience began to cry. The commissioners dabbed their eyes. Judge Lindsay seized the opportunity to point out that the new hospital “is for this type of individual . . . It is not the human garbage dump that they”— meaning Carolyn Hall and her neighbors —“are talking about.”

Many of the MacGregor residents went home feeling remorseful. “My heart was in my throat,” Carolyn remembers; it had been a shock to see that frail girl, to see the human mechanism so bollixed up, and to be reminded that every community has a moral obligation to care for the helpless, for the true have-nots. But after a few days the neighbors began to realize that Evelyn Bell’s mute testimony had played right into the hands of Judge Lindsay. Wouldn’t he have known, the effect such a display would have? People in the neighborhood began calling it political hardball.

To Be Rich and Black

If the residents of MacGregor Way have learned one thing from their involvement in the hospital controversy, it is that power—real power, as it is serenely manifested in River Oaks—still eludes them. In Houston power resides in the boardrooms of the fortieth floor, and the few blacks who operate in those ethereal precincts have learned to use their influence sparingly, and then with great discretion.

Quentin Meese is one of those few. He is chairman of the Harris County Hospital District, which operates the county’s public hospitals, and is on the board of the Texas Medical Center. He came to Houston with the YMCA in 1950 and was the guiding light in the founding of the Houston Urban League. Perhaps more than any other black man in the city, Quentin Meese is welcomed in the chambers of power, for he knows how to go about his business—a quiet word here, a pointed suggestion there, but always with a smile. In his polite and modest fashion, Meese is a great man. In the angry sixties, when other cities were in flames, Meese held his city together. “Everybody doesn’t know what Quentin has done for the black community,” says Carolyn Hall. “This town could have burned too, but it didn’t because of Quentin Meese.” He lives on Calumet, in the North MacGregor area.

On several occasions when his neighbors might have used his influence, they have chosen not to ask. “We know Quentin is there if we need him,” they say. “We just can’t call on him unless it’s absolutely necessary.” In any case, they recognize that Quentin Meese has an obligation to a larger community than the one he lives in: to that vast class of indigents whose lives depend upon Harris County’s public health facilities.

And so the dilemma that people in MacGregor face is this: they may have money, but they are separated from real power by their race. Now, on the hospital issue, they find themselves separated from the larger needs of their race by their own material interests—that is, their class. To be rich and black is to be, in a queer way, nowhere.

The emotional confusion such people have about their place in society makes them easy prey to sentiment. When Harris County purchased the nursing home on North MacGregor that it plans to make into a community hospital, the members of the hospital district board chose to honor their chairman by naming it after Quentin Meese. As a result there has been none of the community protest that has characterized the proposed psychiatric hospital. “Deep down within us, we feel that because it was named the Quentin Meese Center, it’s not going to harm us in any way,” explains Carolyn Hall. “I don’t know what we can do if they decide to make it the psychiatric hospital.”

As a matter of fact, even before the residents of MacGregor began their protest, the judge already had a name in mind for the new hospital. He wants to name it after Myrtle Fonteno, a black Republican he appointed to the board of the Harris County Mental Health and Mental Retardation Authority. Myrtle Fonteno died two years ago. Judge Lindsay believes the new hospital will be a monument to her memory.

Meeting of Opposites

On a hot August evening the political leaders of Houston gathered at the Chinese consulate on Montrose. It was one of those queer, opposites-attract convocations that people scarcely remark upon anymore, and yet are there any two places more disparate than Texas and China? If you stuck a hat pin into Houston and pushed it through the planet, you could poke a Chinese in Chungking.

On the menu were roast duck, prawns, fish in a spicy bean sauce, and a vinegary pepper soup that made even Texan eyes water. The dinner was served in the Hall of Culture.

Anthony and Carolyn Hall were in attendance. Carolyn wore a black and white silk “go-anywhere kind of dress” (she is still a public school teacher). Recently the city council had unanimously passed Councilman Hall’s resolution opposing the placement of the hospital in the MacGregor area—an action that had no effect other than to surprise the county commissioners and annoy Judge Lindsay. Sometimes it seems that Texas and China have more in common than the City of Houston and Harris County.

Councilman Jim Greenwood was making this point to Judge Lindsay when Carolyn Hall walked past. “Oh, Carolyn,” said Greenwood, “I was just telling the judge that the city and the county should work more closely together in the future. Don’t you think? Like on this hospital thing.”

Judge Lindsay and Carolyn Hall smiled coolly at each other. “We’re going to put a wonderful facility over there on MacGregor,” said the judge.

“Not if we can help it,” Carolyn replied, as politely as possible.

Later the judge complained, “There’s just no reasoning with these people.” Carolyn said the same about him.