This story is from Texas Monthly’s archives. We have left the text as it was originally published to maintain a clear historical record. Read more here about our archive digitization project.

He waited in the dark. It was late and the countryside was quiet, somehow sleeping through the blare of the train. Nobody heard the whistle as a warning anymore. He jumped off onto the tracks.

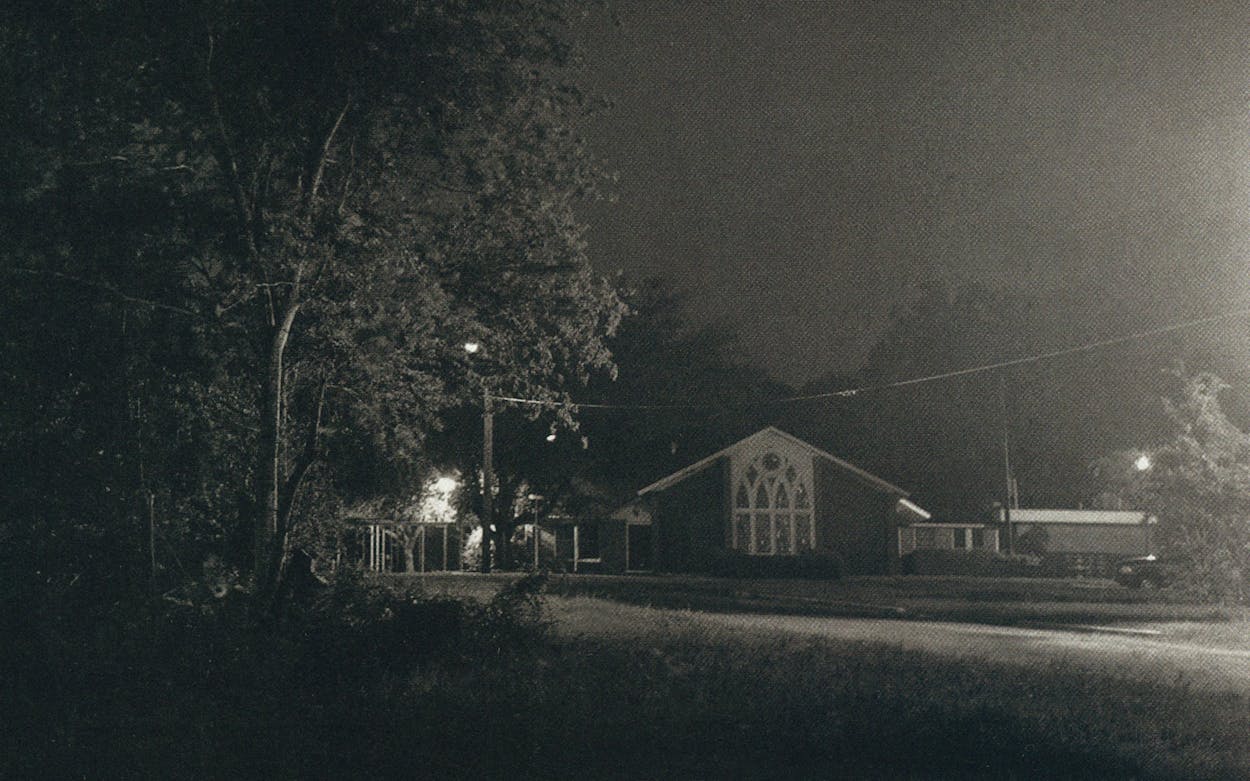

I tried not to kick up any loose gravel. It was a little before midnight on Saturday, May 15, and though the occasional car whizzed past, Main Street was deserted. As I walked toward the church, the wind blew quietly and rustled the leaves of the trees, which were lit with a late-night halogen glow. I had seen enough scary movies to enjoy the growing tingle of fear. I kept walking. With each step, the trees got unfriendlier and the silence falser.

I stopped at the corner of Summit and Ratliff streets, behind the United Church of Christ and next to the railroad tracks. The fear was becoming a pounding dread. I was at the center of the streetlight’s arc; beyond was an abyss. Somewhere down Ratliff Street there was an open two-car garage where a white Acura was still parked—where, in the early hours of May 1, someone had bludgeoned to death the church’s minister, Skip Sirnic, and his wife, Karen. I had planned to walk down that road to see what the killer saw and maybe to answer the question everybody in the town of Weimar was asking: Why?

The bright light gave no comfort. I felt marked, ridiculous. The dread turned to panic, and the warning signs—wordless but unmistakable—screamed in my head. Something evil still abided down that road, alongside those tracks. Only a fool would go there now. Maybe in the morning, in the sunshine, with company. I got the hell away.

At nine-thirty the next morning I sat in a pew at the church, known as the UCC, alongside 150 mourners. The guest minister, the Reverend Jim Tomasek, opened his sermon by reading from Murder in the Cathedral, T. S. Eliot’s play about the killing of the archbishop of Canterbury in 1170: “We are afraid in a fear which we cannot know, which we cannot face, which none understands.” The members of the congregation sat quietly, some still dazed, as Tomasek spoke of the helplessness and abandonment they were feeling, the anger and hurt. “There is always this kind of evil among us,” he said, “when people somehow become enraged in some mysterious way we don’t understand.” It had been only two weeks since the murders, but the future was the important thing. “We need to deal with what is,” he continued, “but let the present lead us into the future.” Good would triumph in the end, the good created by God’s love, “a love that is only interested in the welfare of the other.”

In the Bible, good is always triumphant. “No ills befall the righteous,” reads Proverbs, “but the wicked are filled with trouble.” The Sodomites were obliterated; Job kept the faith and was rewarded. The people of Weimar have heard these stories their whole lives. They believe that living right will bring the good life, and for the most part it has. They believe in an orderly world and an all-powerful God. They couldn’t understand how something so evil could happen to two people so good—two of God’s finest, who had lived their lives for their community and taught God’s love by example. They couldn’t understand how something like this could happen in Weimar, where few remembered a murder ever being committed. And they couldn’t understand their responses. “People here can’t believe the hatred, wrath, anger, and venomous attitude in their hearts,” says the Reverend Mark Miller, the UCC’s conference minister. “They have to decide whether they’re going to be controlled by evil or guided by good.”

That was getting harder all the time. The man who killed the Sirnics was turning out to be more vicious than anyone in Weimar, or Texas, could imagine. Soon the drama would capture the country’s attention too—an unfolding In Cold Blood that got colder every day.

In the cool of the evening he walked alongside the garden. At one point this had been wilderness, but she and her husband had cleared the brush and planted flowers and vegetables. Now it was the first of May, and the roses were in first bloom. He walked into the open garage. He grabbed a sledgehammer from the closet.

Up until lately, hardly anybody knew Weimar existed,” says Reverend T. L. Craig, Sr., an elder of the St. James A.M.E. Church. “‘Weimar? Where? Never heard of it!’”

I had driven past the exit on Interstate 10 a hundred times, but I’d never gotten off. Weimar (pronounced Wy-mer) is not as quaint as Smithville or as bustling as La Grange, and it’s not a major interchange like Columbus or Schulenburg. It’s tucked away off I-10 halfway between San Antonio and Houston. The exit has a Dairy Queen, a Ford dealership, and two gas stations, neither of which are open late at night. The town has two motels and no fancy bed-and-breakfasts. Half the stores downtown are closed or in a state of relaxed disrepair. The Antik Haus just closed for good. The business of Weimar isn’t tourism but farming and processing farm animals.

It’s been that way since the town was founded in 1873. Back then it was called Jackson Station, a stop on the new railroad. Later, as more and more Germans and Czechs arrived, its name was changed to Weimar—perhaps because it reminded them of the old country, or perhaps because they reckoned they needed a more Teutonic moniker. The cemeteries are full of immigrants with names like Kupenka and Cejka, and their descendants are still around. The population of Weimar has hovered near two thousand for years. Some residents moved there to escape the big city, but most are natives who never left the rolling hills and pastures of Colorado County.

As in the past, the railroad is still a big part of life in Weimar. Forty trains roll through every day, blasting their horns incessantly as they cross the country roads and downtown streets. Some go slow; some speed up to about 30 miles per hour. The town has also always been known for baseball and sausage. Men in the area have been playing the nation’s pastime since the turn of the century. The remarkably comprehensive town museum pays homage to Weimar Veterans Park, the first lighted baseball field between Houston and San Antonio, which was built in 1948 and is still in use. And for years people have been driving to Weimar to get their sausage at Kasper’s, an old-style meat market built in 1917. “We Slaughter Our Beef and Pork at Our Local Plant—No Imports,” reads a sign on the wall, which hangs across from a vintage photo of La Grange’s Chicken Ranch.

Although Weimar has a reputation as a nice place to live, its history isn’t bloodless—it was on the frontier, after all. In 1895 two doctors got into an argument and a gunfight; one was killed, the other wounded. “The affair is much regretted and has caused great excitement,” the local paper reported. Another time, bullets flew when two men fought over a dog that was chasing some sheep. For the most part, though, violence in Weimar has been rare. People never locked their doors at night or slept with the lights on, and they left their guns in their cases. “It’s a quiet town with friendly people,” says Mayor Bennie Kosler. “Everybody knows one another. No one has ever gotten mugged or anything like that.”

One reason that Weimar has been so quiet for so long is that it’s extremely religious. There are thirteen churches, one for every 150 residents. My first glimpse of the town, from a couple of miles away on FM 155 South, was the tall steeple of St. Michael’s Catholic Church, an old-style German edifice built in 1913. (Weimar is nearly three-quarters Catholic.) Driving in one night from the other direction on 155, I saw a blue neon cross floating in the sky. It turned out to be the steeple of the 111-year-old Trinity Evangelical Lutheran Church in New Bielau, five miles to the south. Weimar has Methodist, white Baptist, and black Baptist churches, a Church of God and Christ, and the UCC, which is a union of two denominations: the Evangelical and Reformed Church and the Congregational Christian Church. With 385 members, the UCC is one of the larger Protestant congregations in Weimar.

For as long as anyone can remember, the UCC has shared a minister with Trinity Evangelical, which is its sister church. They hired one back in 1988, but he was no country preacher. The wiry man with the bushy mustache and thick eyebrows insisted on being called Skip, not Reverend Sirnic. In a denomination not known for its frivolity, he told stories and jokes from the pulpit. He called children up to the altar during services to tell them stories. He walked down into the congregation to speak. In his sermons he would use examples from his own life, which wasn’t perfect.

He had never liked his own country much, and they had never liked him in this one. Even in prison they didn’t like him. He lived alone, and he would die that way: living by his own rules, making his own choices. In his younger days he looked soft and womanish, but he became hard and mean. He was short and powerful, with a tattoo of a snake on his arm and scars on his head and hands. He had changed his name so many times he didn’t know who he was anymore. He wore wigs, glasses, even, some swore, a dress. He rode the rails—the country’s secret highway—unseen. The cops said he was like a ghost.

Norman “Skip” Sirnic was born on May 2, 1952, in Sharon, Pennsylvania. Twelve years later his parents divorced, and he moved with his mother to the Panhandle town of Friona. After graduating from Friona High School, he went to Trinity University in San Antonio, where he met and married a woman named Angela Skaggs; they had a son, Nathan. He went on to Vanderbilt Divinity School in Nashville, was ordained in 1977, and served at three Texas UCC churches (in Friona, Riesel, and Bryan) before settling in Weimar. By then, he and Angela had divorced. In 1990, Skip married Karen Foltermann, a biochemist seven months his senior, whom he had met in Bryan.

It takes Weimarites a little time to get used to strangers, and it took Skip time to get used to living in such a small town. He had come as an interim minister. “I need to pause and assess my life,” he told his father, Norman, explaining why he had taken the assignment. But he liked this particular church, and its members liked him. He was one of them. He was divorced, like some, and a workaholic, like most. He didn’t take himself too seriously, and he was never condescending. “He was a human being like everybody else,” says his brother, Mark, who is a UCC pastor in Colorado and who visited him often. “When you take time to get in touch with your own weaknesses, it gives you compassion for other people’s weaknesses.”

Skip, in turn, liked them, because he felt like he belonged. He told his father that he was happier in Weimar than he had ever been. “The people were genuine, and they accepted him as a person,” Norman recalls. “Skip said that in other towns they had put him up on a pedestal, but in Weimar he could go to picnics, chase the kids, play volleyball, have a beer if he wanted.” Church member Kelly Janak gets tears in his eyes when he talks about his children wrestling with Skip at the weekly church volleyball games. “He was just family,” Janak says. At picnics Skip was the one who slipped the ice cubes with plastic bugs into someone’s tea and filled the balloons with water. A gifted thespian in high school and college, he was the ham who organized church plays, usually playing the villain.

The thing his congregation loved the most about him was that he practiced what he preached: compassion. Nearly every person I spoke with at the UCC had a story of Skip driving to Houston or Austin to visit someone in the hospital. He called on three dozen shut-ins every month. He started the Caregivers, a group that made sure every member of the church had someone who checked in on him or her regularly. He was always starting projects to get people involved in the community, from a food drive to an adopt-a-flower-bed program. He was on the Ministerial Alliance, an interfaith group of Weimar churches. He was the president of Colorado County Child Protective Services. “He was especially good with kids,” says one parishioner, who—like many interviewed for this story—was too anxious about the killings to have her name used. He was a counselor for children at Slumber Falls Camp near New Braunfels, and a personal and marriage counselor for everyone else. “Everybody went to Skip for counseling,” remembers a woman whose wedding ceremony was performed by Skip on his fortieth birthday. “That tells you something about the man,” she says.

His sermons were somehow both lighthearted and serious. “He had a way of delivering his message that you felt ‘He’s talking right to me,’” a parishioner remembers. “He always made the littlest guy feel so important,” says another. “He brought out the best in people,” says Janak. “He would make you do what came natural to you, what you felt the Lord would like.”

Karen became his partner in all things, singing in the church choir and serving as the church secretary. “Skip always preached about the light: ‘The light will shine through, the light will set you free,’” says Janak. “Karen had her own light.” Soon after they moved to Weimar she began planting flowers and plants around town, at city hall, the museum, the library. He joined her, working in the soil around the monotonous brown sixties-era UCC building. The garden, particularly behind the parsonage, where they lived, grew more and more elaborate: roses in a giant star on the lawn; tomatoes and green beans; purple, red, blue, and yellow flowers. Whenever Skip wasn’t working with people, he and Karen were working in the garden, stopping to smile and wave to the engineers as the trains passed. The garden was dirt therapy, they joked, a way to see tangible evidence of their work. With people it wasn’t always so clear.

On the night of Friday, April 30, Skip called his mother in Lubbock around ten. She had undergone open-heart surgery the week before, and he wanted to check on her. Then he and Karen went to bed. It was going to be a busy weekend: Sunday was Communion Sunday, and it was also Skip’s forty-seventh birthday.

When Sunday came, however, Skip didn’t show up for the nine-thirty service. His pickup wasn’t in his garage, and some figured the birthday celebration at New Bielau, where he preached at eight, was running late. Jim Bibee, who was liturgist that day at UCC, started without him. Everyone knew the routine: Hymns were sung and prayers read. Skip had picked several Scriptures for the day; Bibee read them and added his own comments—a sermonette, he later commented. By this point the congregation had become alarmed; it wasn’t like Skip and Karen to be this late. Thinking the couple had been in some kind of accident, Bibee led a moment of silent prayer for them. Communion was served. Finally, with about ten minutes left in the service, the UCC’s president, Ted Neely, walked over to look in the parsonage. He came back visibly shaken and walked to the front of the church. He stopped for a moment, trying to gather his thoughts. It was obvious that something was terribly wrong. “I have a horrible announcement to make,” he stammered quietly into the microphone. He paused and put his head in his hand. “Skip and Karen are dead, and their home has been ransacked.”

The congregation sat stunned. Bibee led a short prayer. Usually parishioners were ushered out row by row. On this day, some sat and cried, while others stumbled out.

For a long time he was just another hobo—hopping trains, living in migrant camps, working in the fields. He might steal something here or there, sometimes a car. He only hurt a few people, fools who had gotten in his way. But then he changed. How free could a man be? How far could he go? And who could stop him?

Twelve hundred people, including more than sixty ministers, flocked to the UCC for the memorial service on May 6. From the pulpit, Mark Sirnic asked the question on everyone’s mind: Why? “This was not God’s will,” he said. “This was a human choice. . . . God gave us choices, choices between good and evil, choices between love and hate, choices to either destroy or create.” In words that many would fondly recall over the next several weeks, he spoke of Skip and Karen’s garden and of the spiritual seeds they had planted in everyone. It was their obligation now to “cultivate beauty and goodness and bring the fruits of spirit and wonder into the lives of other people.”

Reverend Glen Schoeneberg, a Weimar native who is the UCC pastor in nearby Burton, spoke for the longest time. “The world is an imperfect place,” he said. “Evil things happen—sometimes by cause and effect, but sometimes simply by chance.” Some in the church that day were no doubt thinking, So why pray? If the whole world is in His hands, what good is prayer if it can’t prevent something like this? Schoeneberg had an answer: If God could intervene to prevent all evil, we would just be puppets, incapable of love, which we’re clearly not. “We are free, free to err, free to be afflicted, free to be affected by evil,” he said, “but make no mistake about it: Our faith in an omnipotent and omnipresent God will not be disappointed. Evil happens, death sometimes occurs, but ultimately it cannot win. That’s the Good News of the Scripture. Ultimately, God will not let those things separate us from Him.”

The news wasn’t so good in Weimar. “Nobody here, even the old-timers I’ve talked to, ever remembers a murder in Weimar,” the chief of police, Bill Livingston, told a reporter. In fact, someone had killed a local man in a bar brawl in 1981. But that had been a drunken argument; this was sick, mean, evil. People speculated that the killer had been crazy or high on drugs. He stole Skip and Karen’s pickup truck, their VCR, and a video game. He left the bloody sledgehammer leaning against a bedroom wall.

“We don’t think it’s someone local,” Mayor Kosler said when the news broke. People from Weimar just didn’t do things like this. Chief Livingston said much the same. They were clearly trying to calm the people of Weimar, many of whom, for the first time in their lives, began locking their doors and windows at night. A reward of $10,000 was offered by Hill Bank and Trust.

On May 13 the Weimar Mercury reported that Livingston had said of the murder, “It looked like rage.” To some this meant that Skip had known the killer. No one wanted to consider the possibility, but it gave rise to some interesting rumors. “It ain’t random,” one local said, noting Skip’s leadership role at Child Protective Services. “He had taken a child away that very day.” Others thought it was a troubled drug abuser Skip had counseled: “We have drug addicts in Weimar just like every city has ’em.” There was a rumor that he had tried to sell a coin collection on the Internet; maybe it had been worth a lot of money. A Catholic woman mused that the killings may have had something to do with Skip’s divorce.

For two weeks nothing much happened in Weimar. People relaxed a little; the murders surely were an aberration. “They seem to be going back to sleeping with their windows open,” said someone the next town over. Then, on May 25, came word of the first big break in the case. The good news was the police had a suspect. The bad news was he had killed the Sirnics at random, and he had killed before.

He had a ritual. He waited until after midnight, then broke in through the garage, carport, or back of the house. He found something hard and heavy and attacked their heads, beating them so viciously you couldn’t tell who they were afterward. He took pleasure in their agony. He covered them with a blanket or a sheet, then casually left the weapon behind. He didn’t care about his fingerprints. It was almost as if he didn’t care about getting caught.

Rafael Resendez-Ramirez was a Mexican national in his late thirties with a twenty-year criminal record—including burglary, aggravated assault, and felony possession of a firearm—in Texas, New Mexico, Florida, and other states. He had been caught and deported several times and had served time in U.S. prisons. He went by at least thirty aliases and five birth dates and rode the rails, living the hobo’s life. He had chosen the Sirnics’ home possibly because their garage, where their pickup was parked, faced the railroad tracks. (The parsonage looks like any other house and is separate from the church, which is at the other end of the block.) He was identified because DNA tests concluded that the Sirnics’ killer was also the killer last December of Claudia Benton, a doctor who lived in the West University Place neighborhood of Houston. Resendez-Ramirez’s fingerprints were lifted from Benton’s red Jeep Cherokee, which was stolen after her murder and later abandoned in San Antonio. Benton—who lived one hundred yards from the train tracks—had been raped, stabbed, and brutally beaten to death with a statuette. The news about the DNA tests substantiated at least one fear: Karen had been raped. Another rumor went unproved: The violation had occurred both before and after her death.

On May 28 the Sirnics’ truck turned up in San Antonio not far from where Benton’s Jeep had been found. There were reports that Resendez-Ramirez had been spotted there walking along the railroad tracks. If Weimarites felt relief at having a face and a name to go with the murders, they were terrified at the randomness of it all. A crime this heinous needed a reason. Weimar needed a reason.

America’s Most Wanted came to town at the end of May and filmed a second segment on Resendez-Ramirez (the show had already filmed one after Benton’s murder). It aired on June 5, the same day I drove through Weimar en route to the Fireman’s Festival, a yearly shindig held eight miles away in the town of Oakland. When I went by the UCC, the police tape around the parsonage was gone. Perhaps some kind of closure was coming. I saw in the Mercury that the reward had grown to $35,000. Soon after I arrived, I met up a woman I’d come to know as a source of reliable gossip. She did not have her usual friendly look. “Did you hear?” she asked. “Another woman. Weimar is gonna really be . . .” She trailed off, exasperated. “I’m gonna keep all my doors locked day and night. I don’t care. I don’t care.”

Josephine Konvicka was 73. She lived alone in the house where she had lived all her life, about a mile from the railroad tracks and three and a half miles from the Sirnics, just over the line in Fayette County. She usually watched TV until eleven or so and then went to bed. Sometime in the wee hours of June 4, someone broke into her house through an unlocked rear window, bashed in her head with a grubbing hoe, ransacked the place (looking in vain for her car keys, said police), and left. “She was the sweetest, dearest little old lady,” said one of her neighbors. “She would not have hurt a fly.”

Word of the killing swept through Weimar like a summer storm. According to one source, Konvicka was found with the grubbing hoe lodged in her head. The area had a tormentor, a killer who took delight in terror. The lights came on again; doors were locked. Some residents, especially the elderly, went off to spend some time with relatives in towns and cities that had no railroad tracks. “A lot of these older people have lived in these homes for fifty years,” one local whispered, “and they don’t have a clue where the key is.” Gun stores sold out of guns; hardware stores sold out of locks, security lights, and alarms. Weimar was not used to being a town full of victims, and it was hard to tell if people were more scared or angry. “He’s playing a game with us,” former mayor Julius Bartek told me. “I feel sorry for him if he tries to play that game at my house.”

By the end of the weekend the game had gotten deadlier. Within 36 hours of Konvicka’s butchering, 26-year-old Noemi Dominguez was raped and bludgeoned to death in south Houston. She lived near the tracks. Her car was missing. And now police officers in Lexington, Kentucky, were saying they were sure Resendez-Ramirez was the guy who in 1997 beat a college student to death with a fifty-pound rock and beat and raped his girlfriend, leaving her for dead (she somehow survived). They had been talking late at night, down by the railroad tracks.

The authorities began using the term “serial killer.” On June 8 a task force was formed in Houston comprised of fourteen law enforcement agencies, including the FBI and the Texas Rangers. Before long, two hundred cops and federal agents had joined the hunt. Posters with various mug shots of Resendez-Ramirez went up in every store window in the area. He looked arrogant, with hard, soulless eyes. Terrified locals saw him everywhere they looked. Police officers in Weimar and the nearby towns of Schulenburg and Flatonia doubled their patrols. “We’re getting twenty calls an hour about suspicious persons,” said Schulenburg patrolman John Sampson. “We’re searching trains, meeting them every ten minutes.” Resendez-Ramirez had become the bogeyman. At first the police were too politic to elaborate on what he had done to his victims, but finally their horror overcame protocol. “He is brutal,” said Ronald Walker, a spokesman for the task force. “In all instances there are massive head injuries. It’s a blitz-type attack. This is a purely mean man.” Clint Van Zandt, a profiler, would later tell CBS News, “This is someone who likes to use his hands. He likes to get up close and personal. He likes to see the life ebb away from his victims as he kills them.”

“Generally the serial killer has his reasons for killing, though they only make sense to him,” former FBI profiler Gregg O. McCrary told the Dallas Morning News. What were Resendez-Ramirez’s reasons? What had caused him to go from aimless hobo to frenzied killer? Maybe, as one Methodist minister in Weimar thought, an evil spirit had flagged down his restless soul. Maybe it was simpler. “This is a thrill ride for him,” says McCrary. “In his mind, he’s winning.”

Sometimes he would steal a car, but he would always abandon it and get back on the train. He could go anywhere he wanted. He could disappear.

On Friday, June 11, I went back to Weimar one last time. It was the weekend of Gedenke, the town’s yearly birthday festival (“gedenke” is German for “remember”), and everyone was in a weary frenzy. Two days before, at a Schulenburg town meeting, Fayette County sheriff Rick Vandel had sent a chill through locals by saying that serial killers kill until stopped: “He’s not going to stop until he’s caught.” The day after that, someone was sure that he had seen Resendez-Ramirez in Weimar. There were rumors of a shooting. One hundred officers from the task force stopped and searched trains in Flatonia, a major north-south and east-west rail intersection. The reward had gone up to $60,000. Gedenke began in earnest the night I arrived. On one side of the railroad tracks were arts and crafts booths, a Latino band, and a sausage-on-a-stick booth; on the other were carnival booths, rides, and a country band. It was hot, and the two bands played to sparse crowds. The rides, including the terrifying Zipper, sat mostly idle, and the games went unplayed. In a small antiques shop on Jackson Square, a small group huddled. “He’s gonna keep doing it till they catch him,” a woman said, and her friends nodded. Police officers patrolled in golf carts and cars. In a bar just off Main Street, two men compared guns and gauges. A drunk bragged about what he was going to do to the bastard.

It was about 95 degrees Saturday afternoon, and the parade was mercifully short, with floats from area chambers of commerce, the Weimar high school band playing a lethargic “Louie Louie,” and kids in fire trucks throwing candy to spectators pressed back against storefronts in what little shade there was. Afterward, many fled the festival for the air conditioning of home. At around five a rainstorm blew in, cooling everything down. People started coming out again—first for the Turtle Derby, then for the music. By nightfall more than six hundred people were on the streets: black kids running through the throngs, white men in cowboy hats clapping each other on the shoulder, Mexican American families walking en masse, teenagers holding hands, couples dancing. Several people told me that Gedenke crowds were usually much bigger, but there were still long lines to buy beer and ride the Zipper. The country band played “Amarillo By Morning,” and by the end of the first chorus, I saw five people singing along. The oldies band played “Brick House,” and I saw ten more do the same thing. For a while—within these lights, along these railroad tracks—Weimar was safe and friendly again, the way it used to be. In the silences, though, every thought and conversation drifted back to the killer.

Few knew it then, but earlier that day Noemi Dominguez’s car had been found in Del Rio not far from the international bridge. It seemed that Ramirez had left the country again—or had he? Del Rio is a straight shot to San Antonio by train. “No one around here believes he’s in Mexico,” a resident told me a few days later.” On June 21 the FBI put Resendez-Ramirez on its ten most wanted list. In Texas he was Public Enemy Number One. Lawmen in other cities were starting to call Weimar about their own unsolved killings: A man beaten to death in Luling in 1998; a man found in mid-June in Stephen F. Austin State Park near Sealy; a woman in Hughes Springs. All the victims lived near the railroad tracks.

Investigators, meanwhile, were frantically trying to anticipate Resendez-Ramirez’s next move. It wasn’t a question of if but when. Somewhere out there, the Mexican drifter was one step ahead of hundreds of well-trained American cops. His picture was up all over Texas, and everyone in the state knew his name. He was the lead story on the national news. He was winning.

Weimar was a star too, also for all the wrong reasons. The town would never again be known just for its sausage and baseball. “We’re on the map,” said Reverend Craig with disgust.

They called him Angel.

On the day Resendez-Ramirez made the Top Ten, the Gorham, Illinois, police announced that he was the main suspect in the June 15 killings of George Morber and his daughter, Carolyn Frederick. Weimar’s worst suspicions were confirmed: Resendez-Ramirez was still in the country. It turned out that he had left the U.S. twice—and had even been detained in New Mexico by the Immigration and Naturalization Service, which deported him on June 2—but each time he had returned. He was free to come and go whenever he pleased. It was like one of those slasher movies in which the authorities make one maddeningly stupid move after another while the psycho runs amok. This psycho had come back to Weimar before. Why not again?

Other revelations about Resendez-Ramirez surfaced as journalists joined the hunt. He was known as Angel Resendiz in Rodeo, Mexico, a little town just north of Durango. He had a three-month-old daughter with his common-law wife, who said he was a model husband with no sexual problems. He was “absolutely normal,” she insisted. He’d never been in trouble with the police. “He was quiet and quite serious,” said a court official. “He never bothered anyone.” Of course one of the calling cards of a serial killer is a normal life: John Wayne Gacy and Ted Bundy were model citizens even as they butchered boys and young women. Like theirs, Resendez-Ramirez’s banality made his evil all the more horrifying.

As the reward climbed to $125,000, Weimarites settled in for a summer of fear. Several rued that the big city had come to small-town Texas. “I don’t think it will ever be back to normal,” said a neighbor of the Sirnics. It wasn’t just the locks and lights. It was the new attitude, the anger and hatred, and the choice underlying everything now: follow the good or give in to the bad. Sheriff Vandel was more specific at the Schulenburg town meeting: “Let’s not overreact. Before you shoot, make sure what you’re shooting at.” The last thing the area needed was more dead innocents. If there was ever a time to remember Skip’s sermons, this was it. “This town is very, very scared now,” one woman said, “but I’ve never seen people pull together like this community. They love each other.”

On my last night in Weimar, I went back to the UCC. It was around midnight. Again the streets were deserted. Again I stopped at the streetlight. Again I felt the tingle of fear. But instead of the bang-bang-bang of my heart, I heard the ding-ding-ding of the railroad crossing. A train, as loud as the hinges of hell, chugged past. I stood (bravely, I thought) and watched it roll by Skip and Karen’s garden, which is tended these days by diligent parishioners. That sound might have been the last the two ever heard. At one time the lonesome whistle was a comfort to the people of Weimar, a badge of their innocence—somehow preserved in a wicked world. Now it was a brutish reminder that, at least when the sun goes down, Weimar is no different from any other place.

- More About:

- Crime