This story is from Texas Monthly’s archives. We have left the text as it was originally published to maintain a clear historical record. Read more here about our archive digitization project.

Morning is the time of day when we are least receptive to the lessons of Copernicus. We may understand that our earth is a sphere revolving in the light of the sun, that it moves furiously through space neither forward nor backward, neither into nor out of time, with no apparent purpose and no fate other than entropy. But still a part of our intelligence greets each new day as if celestial mechanics had never been discovered, with a primitive confidence that the sun rises solely for us, to light our way and to warm our blood.

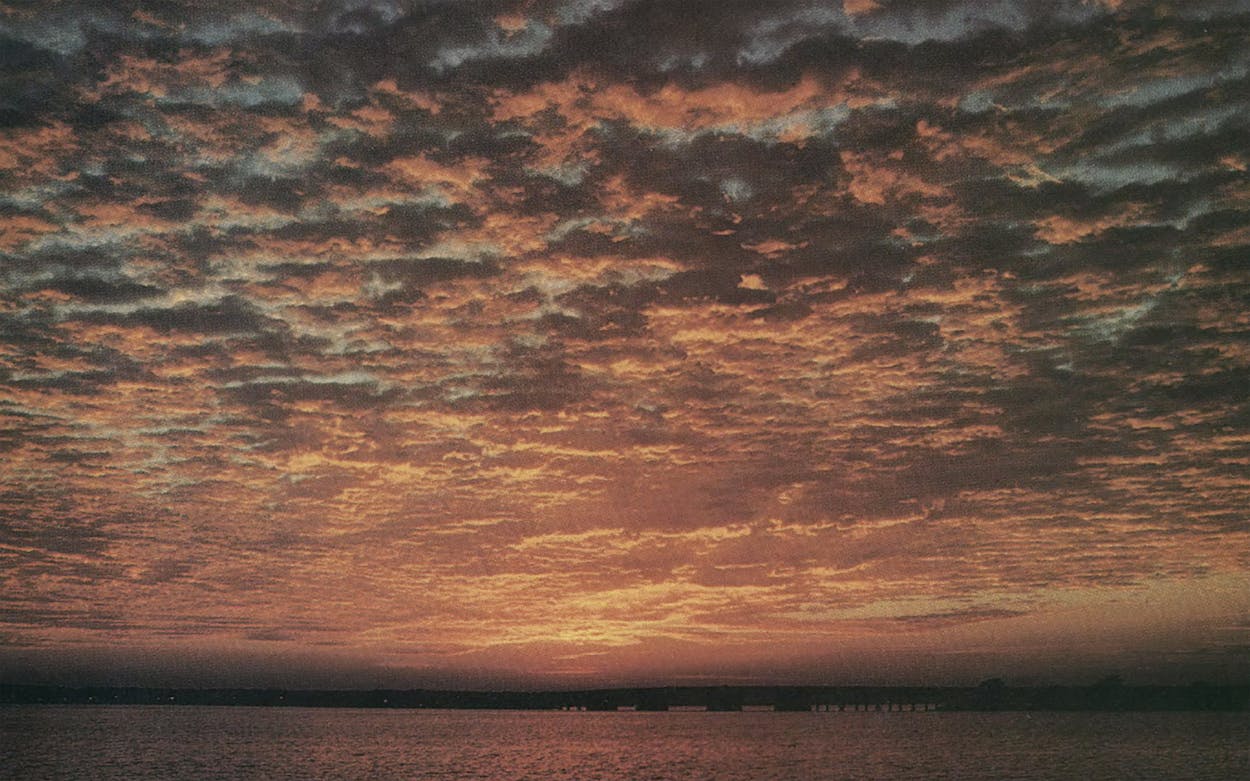

A good Texas morning may contain an unaccountable trace of melancholy, but I think it runs counter to human nature to face the rising sun and feel despair. Our most memorable mornings may have little to do with rousing atmospherical effects; they may be mute and cold, or sodden with stalled Gulf air. We might not even notice that day is coming, never glance at the gauzy whitish circle of the sun as it rises behind a wall of cloud. But we can sense the gathering confidence around us, the world’s resolve to come into its fullest expression.

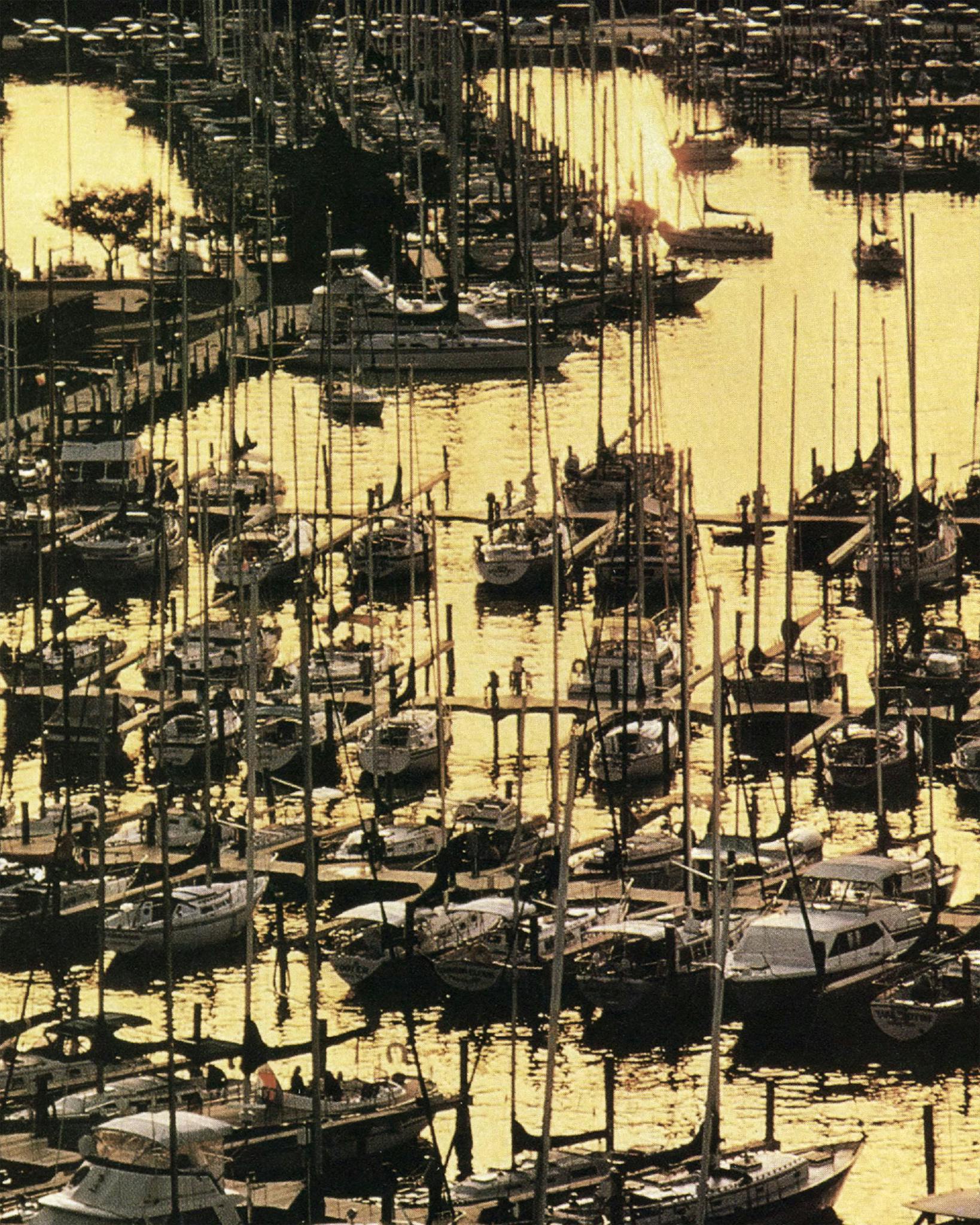

Let’s say it is six a.m. From the unfinished sixty-fourth floor of the Transco Tower, the city of Houston is an endless field of individual lights—porch lights, bathroom lights, headlights—that shimmy in the heavy atmosphere. In the center of that field, monolithic and black as carbon, are the buildings of downtown. Not a single beam of light escapes from their windows, and there is no sunshine yet to give them any texture or relief. Along the horizon, running from south to north, is a thin flourish of cloud beginning to turn orange.

Already the cars are massing on the freeways, and from this height, in this meager light, they appear as a mysterious organic form. There is no question that an alien visitor would immediately identify the dominant life form on earth as the automobile, a creature of unfathomable motives and ceaseless energy, content to circle the dark, burned-out core of its city.

At the distant point where Richmond Avenue intersects the horizon, the sun comes up, seeping over the flat coastal prairie with a steady motion, bright as a welder’s torch. It is a swift and simple event, unannounced by spectacular back-lit clouds or probing rivulets of light. The sun’s plainness is beautiful. A bird sings from the nest she has made in the tower’s ductwork.

As it rises, the sun seems not to cast its light but to hold it in, making the dawn so gradual as to be almost beyond notice. The glassy office buildings, which on another morning might flare dramatically in the rising and subsiding sunlight, merely pass soberly into day. Even when illuminated, Houston is still somnolent, still rich with strangeness, as the compact sun rides the horizon and the nearly full moon withdraws, losing its wattage and melding into the blue of the sky. Straight below, 64 stories down, is a billboard that in this crepuscular moment seems oddly provocative: “Coke Is It.” Is it? If not, what is?

In the neighborhoods below, those people not asleep or already behind the wheel are rising from their beds and moving through their houses. Some of them possess a light-headed serenity, some lurch and stumble and wait for the tide of light to sweep them into awareness. One by one, they are turning off their porch lights, their bathroom lights, and soon the whole city seems to have shaken off its collective dream and regained its grasp.

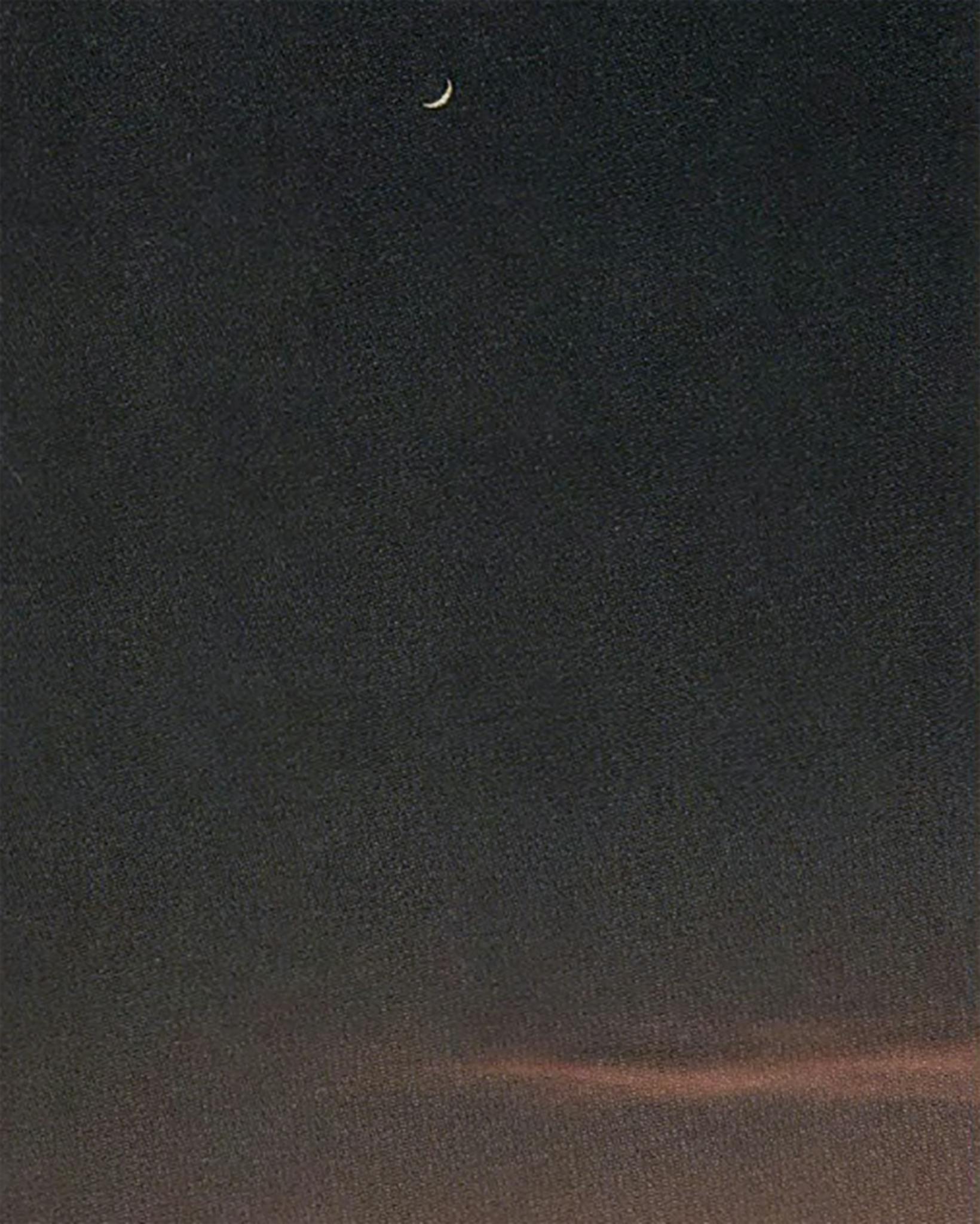

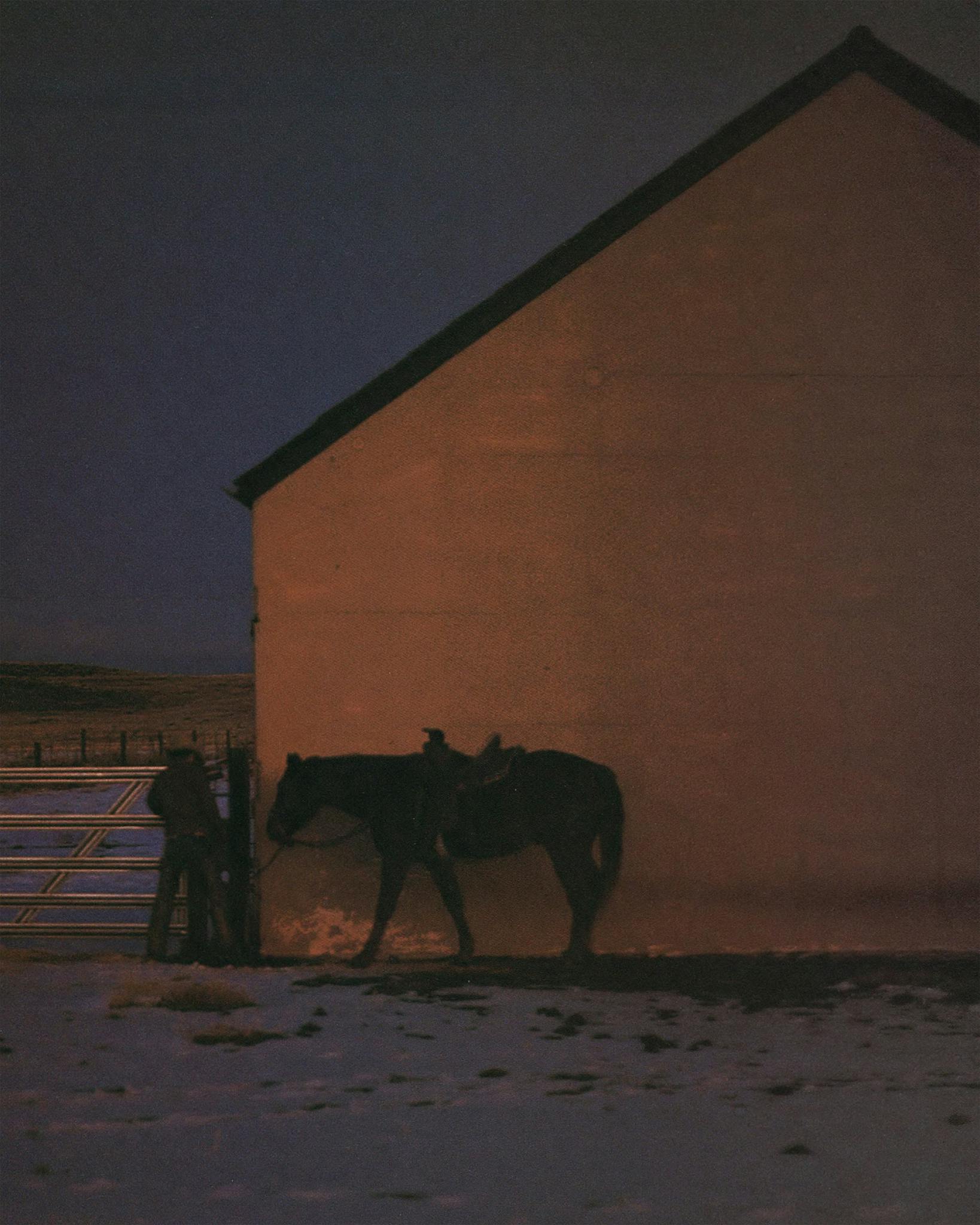

Say it is the same morning, half an hour later. Six hundred miles to the west it is still dark. Standing on a peak in the Davis Mountains, an observer can look out onto a great volcanic plain and see no man-made light at all except for an occasional pair of headlights that cross the bare landscape like a moon rover. There is no wind, and no sound. Shooting stars are visible in the sky, and the moon has disappeared behind a ragged cloud. The landforms themselves—the products of ash fall and lava flow —are indistinct, just hazy shapes in the dark sump below.

Blocked by mountains, the sunrise never quite happens. The dark simply lifts, and the eastern sky turns as radiant in its coloration as if it were a scene painted on glass. But the moment when morning occurs is as impossible to pinpoint as the moment when a soul leaves a dying body. Gradually the world seems less threatening, less solitary, less ancient. Birds begin to rustle in their nests, javelinas trot along the valley roads, and hawks soar above the fractured lava peaks, riding the day’s first warm updrafts.

By this time it is morning all over the state, and even those who remain asleep can feel its effects. It is a light wash over their unconscious minds, a subtle reduction of urgency and detail in their dreams.

In a quiet Fort Worth neighborhood a mother has been up since five o’clock. It was her milk coming in that woke her, but when she walked into the baby’s room to feed him, she found him still asleep, almost the first time since his birth that their bodies had been out of phase. Two months old, he lay there with his eyes clenched tight, his little fingers slowly fanning the air like the tentacles of a sea anemone. His blanket was trussed up about him just so. She wondered if he was dreaming. Did he even know enough of the world yet to construct a dream? She had read that at his age he was amorphous, a creature of sensation. He did not know himself to be distinct. She wanted to think it was her face he saw in his dreams—the emblem of his contentment, the rising sun of his scaled-down world.

Now it is an hour later and the baby has still not stirred. She might have gone back to bed, but she is used to the early morning by now, and this unexpected time to herself is a luxury she does not want to fritter away in sleep. She pours herself a bowl of cereal and thinks about garnishing it with sliced fruit, like the illustration on the box. Finally she decides against it—too much trouble and too much mess. The baby will surely wake up any minute. She can count on her two-year-old daughter to sleep till seven and on her husband’s eyes to snap open exactly at seven-fifteen. As he does every morning, her husband will bound from the bed into the shower and be dressed in five minutes. He likes to be either asleep or awake and ready for action. In-between states make him nervous. He does not even own a bathrobe. She has never understood this—she loves to bask in her own drowsiness.

She watches television while she eats her cereal. A third-string local announcer is talking to a woman about a combination poor-boy art fair and fat stock show. He keeps nodding his head and muttering “uh-huh,” all the while looking like he might reach over and strangle his guest just to relieve himself of his awful boredom.

After a few minutes of this she turns off the television and walks outside to see if the paper has come. The morning is hazy, and the dewy grass is cold beneath her bare feet. She picks up the paper and hurries back to the warmth of the sidewalk. Something holds her there, keeps her from turning back into the house. She is on the verge of some kind of thought; she can sense a vague opportunity forming for her in the still air. For that one second she feels as if she could slip into a trance.

But then the baby’s crying distracts her. She goes back into the house and picks him up, smelling his sour-milk breath, feeling her engorged breasts reacting to his outraged demands for nourishment. She walks outside to nurse him on the front porch, hoping to find that moment again. A large white dog walks briskly and purposefully down the center of the street, his head full of ideas. She can hear the sounds of garbage trucks, the yammering noise of some handyman’s power saw, the raucous courtship call of a great-tailed grackle.

Then another sound: a mourning dove, its notes low and hollow and disturbingly evocative. It’s a sound that reminds her of Girl Scout campouts, of early morning ground fog and bone-chilling cold and an odd, not unwelcome feeling of loneliness. Her baby lifts his head as if in response to the birdsong. Perhaps they are on the same frequency. Perhaps the sound, which is so tantalizing and ungraspable to her, meshes perfectly with his unformed intelligence. For a moment she envies her baby, because that is what she wants for herself: just to be here, just to be part of the morning.

- More About:

- TM Classics

- Photo Essay

- Houston

- Fort Worth

- Fort Davis