The foyer of George H. W. Bush’s office in the memorial neighborhood of Houston is perfectly round, but if you squint really hard, it can look . . . oval. The geometric fantasy is supported by the presence of official-looking artifacts, presidential and otherwise. The guest book where I sign in contains scribbled signatures of visitors famous and infamous (April 10, “Chuck Yeager”; April 18, “Karl Rove, Washington, D.C.”). On one curve of the wall is a framed series of three photos, all taken over half a century in the East Garden on the White House grounds by the same photographer, of presidents and vice presidents at the lunch table: Roosevelt and Truman, Reagan and Bush, and Bush and Quayle. On the other, next to a small bronze statue of George Washington, is a Peter Max painting of the American flag, one of several gifts from the artist while Bush was in office. In the hallways off the foyer, family photos and paintings donated by well-wishers share space with a glass-encased baseball autographed by Joe DiMaggio and a neatly arranged display of medals and crosses given to Bush by governments around the world after his defeat in 1992 by Bill Clinton, which he jokingly refers to, Churchill-like, as having received the “Order of the Boot.”

When he ambles out of his private office, cup of coffee in hand, Mr. Bush seems relaxed and happy, in the mode of a carefree retiree, and he looks like an older version of his trim, preppy self (he turned 79 in June). I had been warned by Tom Frechette, the 24-year-old Josh Hartnett look-alike who handles his press and travel, that the former president wasn’t going to be able to give me or our photographer, Platon, much time. But on this late April morning, FLFW, as Mr. Bush is known in shorthand, seems to have no place special to be. (The meaning of that abbreviation? Frechette says that when the staff had to set up the Internet domain name for the office, someone waggishly suggested “flfw.com,” as in “former leader of the free world.” Mr. Bush liked it, and it stuck.)

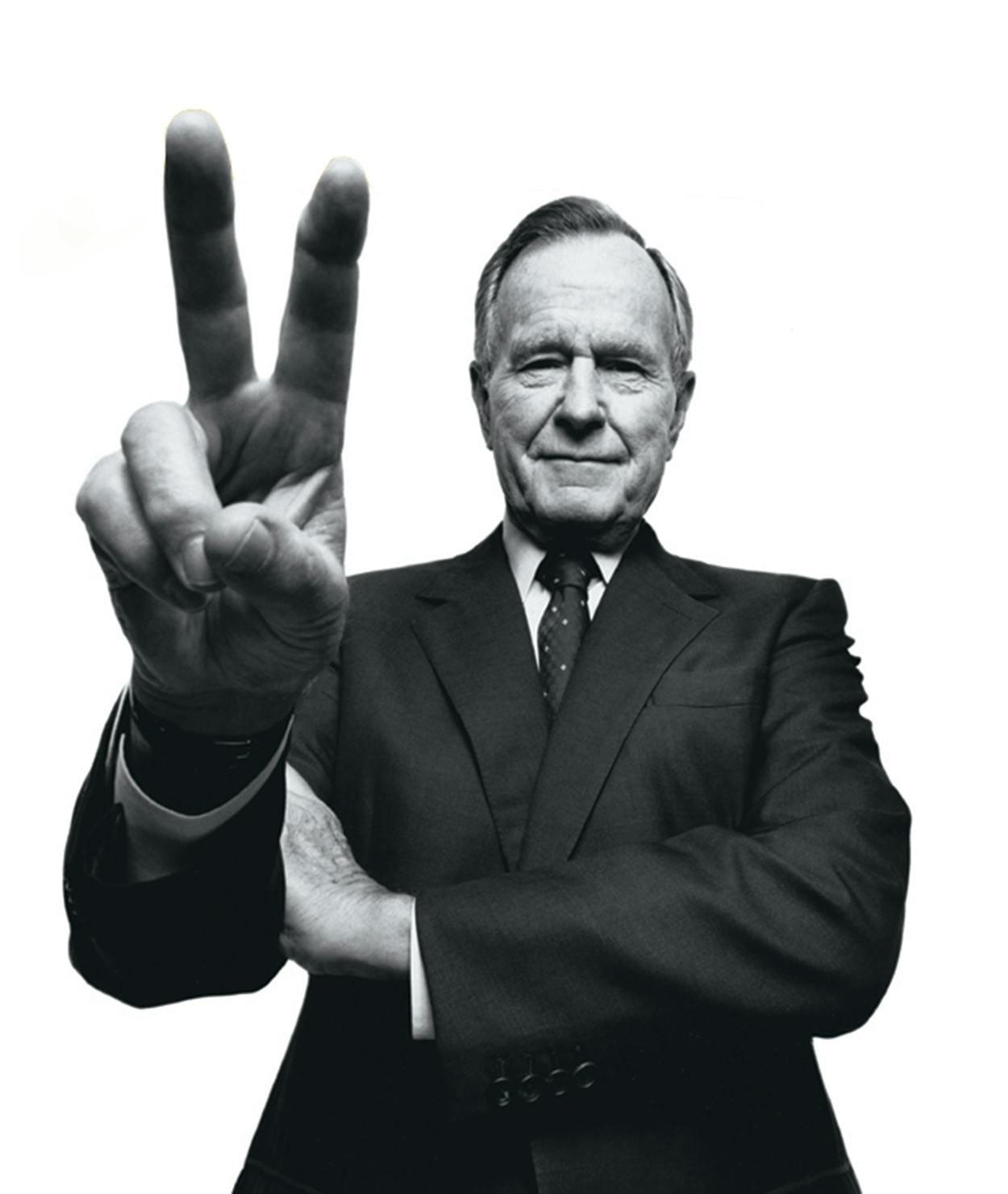

Mr. Bush makes his way to the small, dark conference room where the photos will be taken and greets Platon and his assistants warmly. His time in front of the camera turns out to be casual and jokey—very Bush or, I couldn’t help thinking, very Dana Carvey.

“Mr. President,” Platon says in his full-on British accent, “I’m going to have to explain some of my English phrases to you. When I say you’re ‘wicked,’ I don’t want you to take offense. It means ‘cool.'”

“I’m just getting used to ‘cool,'” Mr. Bush replies. A few seconds go by. “Would you say Brad Pitt is wicked?”

Mr. Bush patiently mugs for fifteen minutes—standing, sitting, grinning, flashing a victory sign at Platon’s request—and then starts to leave. It’s time for our interview. But as we head back to his office, he turns to me and motions to a few framed photos on a table in the corner. “Did you see that picture of me and Jacques Chirac?” he asks slyly. “I just want to be sure you mention that.”

Evan Smith: Mr. President, it’s now been a little more than ten years since you returned to private life. How’s it going?

George H. W. Bush: I don’t think we’ve ever been happier, Barbara and I. There’s plenty to do, and we can control our own time. I have to make a living, so I go out and commit white-collar crime by speaking for a lot of dough, or what seems to me a lot—not compared with my successor, but still plenty. I try to be a point of light, and I’m engaged in certain eleemosynary causes, like M. D. Anderson. So life is full—much fuller than I thought it would be. And we’ve got the best lifestyle, because we spend seven months in our little house in Houston and then five months based out of Maine. We’ll leave in a couple of weeks to go up there, and it’s very different. Neckties come off, there are few drop-ins, and we’ve got a little gym so I can work out. I have my boat there—the sea means everything to me. I’ve been there a part of every summer except one, so there are a lot of memories, and all our kids and grandkids love it, as did we and my grandparents.

ES: What are the responsibilities of a former president to the country?

GHWB: I don’t think there are any. I don’t think there’s a job description. Truman wrote a book, a chapter of which was called “What To Do With Former Presidents,” where he suggested they be honorary members of Congress with no right to vote, but they could sit in on stuff. That has no appeal for me. Of course, with the new president, and before that, with both George and Jeb running for office, I was disinclined to get out there and take positions and write op-ed pieces, and it’s just verboten now, because some enterprising reporter would say, “Look at this. Don’t I detect an iota of difference here between this president and number forty-three?” It’s better just to stay out of the limelight, sit on the sidelines, and go about my life. At times I miss making important decisions. At times I miss seeing my views out there. But it’s unimportant to Barbara and me when compared with the well-being and progress of our two sons in politics.

What’s interesting, I think, is that the press takes your silence as an indication of differences between you and the president. The fact that you’re not speaking out supposedly says something. When a friend of mine like Jimmy Baker or Brent Scowcroft says, “Well, we ought to do more about the Middle East,” the press says, “It looks to us like they’re reflecting what president number forty-one really feels but doesn’t want to say,” which is all bullshit, if you’ll excuse the expression.

ES: We can edit that out.

GHWB: You can print it. At this stage in my life, I don’t care.

ES: Okay.

GHWB: It’s crazy. If I wanted to say something publicly supportive of the president or different from the president, I’d do it. There was a story recently in the New York Times that implied that there seem to be differences. They picked out some phrase I used [in a speech] up at Tufts. And they acted like, Hey, there’s a little running room between the two of them. Well, there wasn’t. It certainly wasn’t intended that way, whether someone interpreted it that way or not. But that’s the big game: What do I really think; what advice do I give our son. It’s better to just stay out of that altogether, and I do. I’m not in the advice-giving business.

The other day, we were in Washington. I went up there to watch Margaret, our daughter-in-law, in a play. Laura and I went over and watched it. Then I went to get a haircut and got back to the White House, and we were with the president and Laura just a couple of minutes after he had done all these briefings and made his overseas phone calls. There he was in his running clothes, and we just sat there and chatted like father and son used to over here on Briar Drive—without advice, without my trying to suggest some direction on some issue, without my trying to outline policy for him or having him do that for me. We don’t need that. I don’t try to be this old, senior former president who’s giving a lot of free advice. I don’t have all the information, to start with, and I don’t have the “need to know” for that highly selective intelligence. And so if I don’t know, why the heck should I pop off? I’ll leave that to Newt Gingrich.

ES: You’re not just any father and son—it’s only the second time in American history that we’ve been in this situation. Your relationship must be different today than it used to be.

GHWB: It’s not different. It’s father and son—it’s about family, it’s about how the girls are doing, how’s Jenna, how’s Barbara. He calls us: “What’s happening down there?” It’s not different in the sense that we treat the president or the governor of Florida any differently than the other three kids. When they come to visit us in Maine—they usually spend a couple of days up there, I wish it was more—it’s exactly the way it used to be. It’s closeness. It’s family. It’s doing things together. It’s teasing each other. It’s not what’s going to happen next with Germany or France or Iraq. I know that must be hard for people to understand, but it’s not what our life together as a family is about.

ES: Can you think back to the first time that you thought of the president: “He’s for real in this job?”

GHWB: I guess it was Inauguration Day. It was icy-cold out during the parade, so when we came back to the White House, I went to the Queen’s Bedroom, where we now stay when we go up there. I got in a hot bath, and [James] Ramsey, who is one of the marvelous people who look after the White House, knocked. “Mr. President!” “What is it, Ramsey?” “The president wants you over in the Oval Office now.” I said, “I’m taking a—” and he said, “He wants you right now!” So I had to put my suit back on and get over there. And we had our picture taken together—the first picture taken of the president in the Oval Office. And I thought, “Well, not back that many years ago, there’s a picture of my mother and me, the first picture that I had taken in the Oval Office.” I think it’s something about the majesty of that office itself—the physical dimensions of the office, the beauty of the office, the symbol of the office—that made it clear to me that he was president of the United States.

ES: You were part of the White House environment for twelve years, and you lived in the White House for four. People on the outside imagine that it’s this extraordinary bubble. Is it impossible to have a real life?

GHWB: I think the current president would agree that you can have a relaxed family life in the White House. People are there to do stuff for you. You don’t have to worry about the laundry or having to cook, although we used to cook on Sunday nights, and I think the president and Laura pick up from the upstairs pantry. There’s a movie theater, a bowling alley, nice grounds on which you can go out and throw a couple of fastballs to your dogs. You can have the dogs upstairs. We had dogs in the White House—Millie’s puppies were born there. And so there is this kind of quiet, personal side that’s protected, properly so, from the public, where you can relax, where you can be informal, where you can have a couple of friends over for a drink. That part is marvelous.

ES: Did you spend much time seeing friends from your private life while you were in office?

GHWB: Not out so much, but they’d come in. I have a friend named Lud Ashley, who was a Democratic congressman and a classmate of mine in college. We have been very intimate friends since college days. When our daughter died, he was there. I could call him up, or Sonny Montgomery, a congressman from Mississippi, and say, “Come on over. Let’s have lunch.” It’s more difficult to go out because of the press van and the Secret Service; so when you get there, it’s not as informal as it is when you go over to a neighbor’s house without the trappings of the presidency.

ES: Today, with the security issues what they are, is life as a president and as a former president a little bit more constrained?

GHWB: It is more constrained, but again, we’re used to the Secret Service protection. And they’re like our sons, except they transfer out after three years. Barbara knows them all, knows all about their families, so you don’t feel like you’re in a scary kind of environment. I think the president feels comfortable with the coverage he has. You have to have it. You can’t try to elude it. You can’t do what these novelists talk about, hiding in the bottom of a car to get away. That’s all entertainment.

ES: I see the current first lady occasionally in Austin, eating lunch with Reagan Gammon and other old friends at Las Manitas. She seems quite comfortable, actually, returning to Texas.

GHWB: Well, she is. We go to Crawford at Easter, and there’s Reagan and [her husband] Billy, wandering around looking at the flowers. The president has a good way of separating out the responsibilities and not burdening the couple of friends who might be there to go fishing with him. It’s amazing how he does it. He’s probably better at that than I used to be. He does his business and then goes off and relaxes and exercises or calls his friends. He does what normal people do.

ES: Let me come back to your life here, Mr. President. Leaving aside the issue of your commenting on what’s going on nationally or internationally out of deference to the president, how reluctant are you to comment on things that don’t relate to the nation or the world but to Houston or Texas?

GHWB: I don’t necessarily feel constrained, but if it has to do with public life—what I think about the education plan before the Legislature—I wouldn’t comment at all. Honestly, at my age, I don’t keep up with it that much.

ES: It’s not on your radar screen?

GHWB: It’s not on my radar screen, and it’s not something that I’d be particularly interested in. It’s funny, when you get older, your interests go right back to the fundamentals, and for me the fundamentals relate to family and, to some degree, sports. Sunday I was out there [at the Shell Houston Open] greeting Freddy Couples, who visited us in Maine. And watching other guys we like, [Phil] Mickelson and [Ernie] Els.

ES: You did a little commentary on television.

GHWB: That’s right. Jim Nance is a great friend. I love doing that. I still like the name-dropping. And when I get around those guys, they all make me feel wonderful. I just had an e-mail from Davis Love this morning, and I like that. I like staying in touch with the ones who are friends, whom I know personally. Then we went over to the U.S. clay court championships and watched [Andre] Agassi win. We’ve known him for years; he visited us at Camp David. Then he came to the White House to play and got rained out. Those things I love.

ES: Are you playing golf yourself regularly?

GHWB: Not regularly, but I’ll start when I get up to Maine. I play badly, but I still love it. I love the game.

ES: What’s your handicap these days?

GHWB: Oh, I don’t turn in a scorecard ever. But I’d probably put it in the high twenties, which is embarrassing.

ES: Back to the non-sports world, Mr. President. Is it difficult to be in your particular situation at times like the ones we’ve seen in the past few months, with the war and all?

GHWB: Oh, yeah. I worry. I do. I think I worry more about it than the president does, just as I worried more about Jeb’s election than he did. I say to the president, “I worry about this.” And he says, “Dad, don’t worry.” They’re engaged. They’re doing their jobs. And they can work off their anxiety by hard work, whereas I sit around and talk back to the TV set. Though I’m disinclined to call up some TV person and say, “You’ve got that wrong” or “You ought not to be treating the president this way.” I churn inside, particularly when I read or hear stuff that is grossly unfair or untrue.

ES: Has the press been fair, in your mind, to this president?

GHWB: I think he’s gotten pretty good press. There are certain exceptions to the rule, but I think it’s been pretty good. Where it’s not, it’s predictable—that so-and-so’s writing that. You don’t expect Paul Begala to worship George W. Bush. So I just tune him out now. He was a fairly engaging person back in the old days, but he’s off my list. As are the Dixie Chicks, which may surprise you.

ES: I want to ask you about that, Mr. President, since you brought it up. There are people who would argue and have argued that the Dixie Chicks flap is an instance of somebody exercising a right that we were fighting to ensure for the Iraqi people.

GHWB: I think you can make that argument. The problem with the Dixie Chicks, as I understand it, is that they were out in front of an anti-war audience in England. They’re young kids, and they got carried away. There’s a tendency at political gatherings to jump out ahead of the hounds. That’s what I think. And now they regret that, because they used to say pleasant things about the governor of Texas, as I understand it. They couldn’t have reversed that much based on Iraq; they’re not foreign-policy experts. I think, and maybe this is too kind, they just got carried away and told the audience what it wanted to hear. Hey, right on!

ES: Could they get back on your list?

GHWB: They’re on my shit list. Which list are you talking about?

ES: I mean, can they redeem themselves?

GHWB: Sure. You’ve got to forgive. You’ve got to. A friend of mine, a very famous journalist, knowing I like country music, sent me a Dixie Chicks CD. I thanked her. And then when the Dixie Chicks did their thing, I took the CD and, just as a joke, because I didn’t give a damn about it, I took my penknife and crossed through their name and sent it back to her. It wasn’t anger; I just thought it would be funny. She sent it thinking I would love them, and I did like their music, but then they said what they said. But they’re young kids. Why not be open about it? It’s nothing compared to . . . Let’s put it this way: I feel differently about the Dixie Chicks than I do about Martin Sheen.

ES: What about Martin Sheen?

GHWB: Dennis Miller says, “You know, Martin Sheen is not the real president of the United States.” He gets a huge laugh. If you asked me “What did Martin Sheen say that you don’t like?” I couldn’t tell you, except I keep seeing on Fox News that Martin Sheen is always listed as the guy who’s strongly opposed to the president. Therefore I don’t like him.

There have always been people like this—Barbra Streisand. I mean, we went through it. We went through the same criticism about the first Gulf war. My Episcopal bishop was out there then, just as the Episcopal bishop is out there now, but I’ll tell you one thing: It hurts more when it’s your son they’re taking on than when it’s you yourself. That’s where the father comes out. It’s much more personal for me. The people [who were after me] I just gave up on. Screw ’em. Let them go do their thing and I’ll do mine. But when it’s your son, you’re hoping that they’ll moderate.

ES: Let me come back to the family. The saying around Austin these days is “Eight years of W., eight years of Jeb, and then [Jeb’s son] George P. will be forty.” Do you subscribe to the theory that Jeb might be president, that P. might be president, that there’s more life to the Bush presidential dynasty?

GHWB: I don’t have hopes of that, but I’d say that looking at the state of Florida—he’s the governor of the fourth-biggest state—and looking at where Jeb is and looking at the great job he is doing and has done and looking at the fact that he was singled out as the number one target to beat by this guy [Democratic National Committee chair Terry] McAuliffe and blew his opponent away by thirteen points—leave out the name Jeb Bush. Does the person who has done those things have potential for national office? The answer would be, “Hell, yeah.” But does he even want to consider it? I’ve never, ever discussed that with Jeb.

George P. is a modest rock star who has a charm about him. I couldn’t ask for a more wonderful grandson. But I don’t think he’s sitting there now—he’s getting ready for his bar exam at the University of Texas—plotting what comes next, like some of these upwardly mobile guys. At graduation from high school, they’re thinking, “I can now run for the legislature. I can be the youngest state rep from someplace.” That’s not what he’s about, and so I have no idea. I do know he’s interested in the political world, and he’s done an awful lot for his uncle and for his dad in that regard. I was so proud of him at Jeb’s inauguration, when he presided as the master of ceremonies. I was sitting there watching and thinking, “This guy’s got a real presence.” He wasn’t overbearing about it, but he was assertive and did a good job. I don’t know what will happen.

ES: I guess I was wondering less whether they are looking to it than whether it’s something you wish for.

GHWB: I wish them great success if that’s what they want to do with their lives, but I don’t think Jeb spends a lot of time thinking about what his next step is. I know George P. isn’t plotting whether or not to go into politics. If they came to me and said, “Gampy, I want to tell you something. I really someday . . .” I wouldn’t say, “Here’s what you ought to do.” But inside, I would say, “Gee, that’s wonderful.” I mean, I’m a grandfather. I’m a father. I’m proud. I love my kids and my grandkids. So there it is. Barbara might give them a little advice, whether they ask for it or not. It’s marvelous the way she lectures them.

Mrs. Bush will do what Mrs. Bush wants. She will, that’s for damn sure.

- More About:

- Politics & Policy

- George H.W. Bush

- Barbara Bush