This story is from Texas Monthly’s archives. We have left the text as it was originally published to maintain a clear historical record. Read more here about our archive digitization project.

When I left southern Mexico for El Norte five months ago, I knew that it would be a long time before I saw my family again. If I had known how hard the journey would be and the difficulties I would face in my new life in the United States, I wouldn’t have gone. But the only job I had been able to find at home in Oaxaca was as a parking-lot attendant, and I didn’t make enough to pay our bills. I had heard many stories about people like me who found a coyote to guide them across the Mexican border into the U.S. Once there, the stories went, they were able to find work.

On the advice of friends in my village I went to Nuevo Laredo, where I hired a coyote for $450. For more than a week dozens of us lived on a concrete slab next to a house on the outskirts of Nuevo Laredo while we waited to be taken across the Rio Grande. We spent another week crowded in a shack north of the river, watching fearfully as each day some of our fellows were crammed into cars that took them to different parts of the state.

By the time I finally got to Houston, I had been robbed of most of the money a friend had lent me. I had less than $100 in my pocket, no job prospects, and no place to stay. Other wetbacks had established themselves in neighborhoods all over the city—in the Heights, near Moody Park, around Chimney Rock, and even across town in Pasadena. But I wanted to live where rents were cheapest, in a neighborhood east of town that I called, for lack of a better name, El Pasillo (“the Passageway”). El Pasillo is Houston’s answer to San Francisco’s Mission District and New York’s Spanish Harlem. It is where Latin American immigrants go when they get off the boat or out of the truck or down from the freight car.

Latin Americans come to the U.S. not because they want to but because economic and political conditions at home force them. Mexicans have an extra incentive. All of us—or at least those of us who are under the age of thirty, as most wetbacks are—have known of someone who emigrated and made good, someone who left for El Norte and returned a few years later driving a shiny new car, someone like my landlord in Houston, Anselmo Mendoza.* For the few months I stayed in Houston, I lived in one of the El Pasillo apartments that Mendoza had bought years ago with money he earned as a bracero. From him I learned what life has been like for older Mexican immigrants. In places such as Houston new immigrants, like me, get to see these winners up close, but we also find out that the big cars and color television sets, the portable plums of Norteamérica, cost more than we knew and perhaps more than many of us are willing to pay.

Anselmo Mendoza worked on a West Texas ranch for sixteen years. With the help of the patrón he saved $9000 and became a legal resident. When he moved to Houston in 1970, he bought a house in El Pasillo that was a long, low structure about fifteen feet across and more than sixty feet long. It was enclosed by a chain link fence on all but the east side, where cars entered the long driveway that led to the garage in the back. Mendoza was its third owner. The previous owners had each built a piece of the house, extending it to the rear to make room for apartments. Mendoza continued their work, converting the garage into living quarters. His improvements made the place what it is today: six rental units. The rents from his sufficient but cramped apartments ranged from $60 to $65 a week, bills paid. During the oil boom, Mendoza never had to worry about keeping his apartments full. There were more people than apartments in El Pasillo, and tenants were subletting corners, closets—any space that was big enough to throw a mattress.

Mendoza’s second piece of property, which he bought in 1975, was about twenty yards by forty yards in size, with three buildings on it. At the rear was a sheet-metal shed where his oldest son, Hector,* did auto repair work. To one side was a house with two apartments on the ground floor and a third in the space that once was an attic. A set of wooden stairs connected them. At the other side, nearly touching the garage, was the house where Mendoza, his wife, and his sons now lived. It was a simple shotgun house, painted turquoise-green like the apartment building. It had a low-roofed extra room in front, added on as a warehouse for Mendoza’s other business.

When he first arrived in Houston, Mendoza worked as a bricklayer by day and as a janitor and porter by night. In the afternoon hours between his two jobs and during weeks when construction was slack, he drove his station wagon to a farmers’ market in fart north Houston, where he bought fruits and vegetables at wholesale rates from the truckers who came up from the Valley. Mendoza sold his wares to housewives and restaurants in El Pasillo. As his business grew, he stopped going door to door and became a wholesale supplier to El Pasillo restaurants and groceries.

In many ways Anselmo Mendoza was a success. He never could have amassed so much money in Mexico, and he could probably have lived in real comfort in America, if he’d wanted to. Undoubtedly, old-timers and peers in his native village, where he was having a house built, called him Anselmito el millonario. But his voice turned sorrowful when he talked about his sons to tenants he had befriended.

“Sometimes I get to thinking,” he told me with the air of a man who had been shamed, “just who is to blame for my sons? Is it me, for being of weak character, or is it my wife, for wanting to spoil them? Or is it this country? Somebody has done them a lot of damage.”

His sons, except for the youngest, who was born in Houston and was only twelve years old, dropped out of school. They hadn’t married, and though they called themselves mechanics, Mendoza said they worked only when they wanted to. The youngest son, he said, already showed signs of following in his brothers’ footsteps. When Mendoza attempted to scold his children, they answered him in English, a language he still doesn’t understand. He complained that when he quarreled with his sons, his wife usually defended them, knowing that they were wrong but wanting to spoil them anyway.

He told me about an incident that began when he arrived home one day with a load of produce. He began unloading it, stacking the boxes and crates in the storeroom at the front of his house, while his sons watched—each with one eye on a television set—from the living room. No one offered to help him. The telephone rang. One of his clients was calling to place an order. After taking it, Mendoza returned to the unloading task, while his sons continued to watch television. When he began reproaching them for their indolence, they got up and went into their bedroom, without responding to his comments.

“Some days I regret having come to the U.S.,” he told me. “In Mexico, at least in the countryside, where people are humble, my sons might have become men, useful men. For the rest of my days,” he continued, the wrinkles deepening on his face, “I’m going to live in Mexico with my wife. But before going, I’ve got to sell all I have.”

In the years between the time Mendoza and I became immigrants, and especially in the last two to three years, the economies of both the United States and Mexico have changed. More Mexicans need to leave home today than in Mendoza’s time, yet we can no longer gain legal status in the United States. Today millions of Mexicans can’t find work on either side of the border, leaving a question unanswered for everyone in both countries. When a man like Anselmo Mendoza sells his holdings in a place like El Pasillo, where is a new Anselmito to buy them? In my passage through Houston I didn’t find him, and I realized that I could never become him.

The One-Hour Job

Most Houstonians who work downtown have probably been to the neighborhood for lunch at Ninfa’s on Navigation, but El Pasillo is the kind of place most people wouldn’t go to without a good reason. An inland island isolated from the city’s traffic currents, El Pasillo is an amalgam of older neighborhoods and towns, bounded by the Houston Ship Channel on the north and by railroad tracks and rail yards on the south, east, and west. Its Magnolia District, on the east end, was once the mostly Mexican town of Magnolia Park. Harrisburg Boulevard, on the south, was the chief artery of Harrisburg, an old and historic village that General Santa Anna burned to the ground before Houston was founded. The Second Ward, on El Pasillo’s west end, was an enclave of European Catholics whose taverns and parks, old-timers say, were off limits to Mexicans. But in the years after World War II, especially during the oil boom of the seventies, El Pasillo outgrew the old hatreds and boundaries and became a neighborhood in its own right.

Today narrow, slow-moving Canal Street is the most venerable Hispanic avenue in Houston. It runs the length of El Pasillo, midway between Navigation and Harrisburg. It is a crowded street, dotted with school zones, speckled with pedestrians, crisscrossed with railroad spurs. Some people on Canal still use clotheslines to dry their laundry, just as in Mexico. The street and its feeders are lined with mom-and-pop businesses: little grocery stores, dry-goods houses, snow-cone and taco stands, barrooms, and bakeries. Every address is just around the corner or down the street from an industrial installation: a marine or oil-field supply yard, a machine shop that makes valves, a plant that rebuilds diesel engines or electric motors. Billboards in Spanish stand at intersections, some of them advertising Mexican products like Mejoral, a brand of aspirin. American-made items are available everywhere, but Mexican immigrants, who probably make up half of El Pasillo’s Hispanic population, prefer brands from home.

One of the people I came to know in El Pasillo was Abel Cruz.* With two other illegal Mexican immigrants about his age—one of whom had a wife and child at home in Mexico—Abel rented an apartment in a house on Canal Street for $50 a week.

The house was an old wooden place, its white paint cracking. Its roof of composition shingles was patched over with sheet metal. The window screens were torn, and the window frames were rotten. The front door was blackened from constant use, and the padlock had been changed so many times that the wood around it was full of gouges. Inside, two single beds with metal frames sat next to a wall, and a mattress on the floor served the third man as a bed. The bathroom faucets were rusty, and the medicine cabinet mirror was cracked down the middle. Someone had removed the shower head, so water flowed straight out of the pipe. The kitchen was furnished with a four-burner stove, but there was no sink; dishes had to be washed in the bathroom.

Abel and his roommates were pioneer immigrants. They came to the United States without papers and without relatives or reliable patronage. They had to establish themselves from scratch, almost alone. Finding a niche can take years, and most illegals are condemned to fleeting and insincere friendships, a hand-to-mouth existence, and a constant search for work. The life is so hard that after a couple of years, most wetbacks give up and go home. Only the lucky, the tough, and the dead stay on.

Abel had been in the U.S. for three years, since he was fourteen. I asked him if his parents had given him permission to leave home. “They were poor, very poor,” he said, clasping the brim of his cap and looking down. “They had to do it.”

On his first trip, he crossed the border near El Paso with only 300 pesos to his name. He made friends with an older man who, perhaps from pity, found him a job on a ranch. Several months later Abel joined the migrant stream, working harvests in California, Washington, Colorado, Pennsylvania, and Florida. Along the way he held laboring jobs in Chicago, St. Louis, and Fort Worth. In his three years north of the border, he had been home only once. While there, he said, he bought a house for his family with $7000 he’d saved. The story was probably not true—most likely Abel had never had any savings—but a lot of wetbacks are full of distant dreams and fading fantasies, at least until they get established.

What was true was that Abel didn’t have a car. He wanted one “to take home to Chihuahua,” he said, as if Norteamérica left a bad taste in his mouth. “I don’t like it here,” he told me, “because almost everybody you meet is either an old drunk or a young drug addict. We wouldn’t put up with drugs in my village.”

Abel was the one who told me how to find temporary jobs through radio station KLVL on North Ennis Street, just half a block from Canal. KLVL is a Hispanic institution, unique in the city and in Texas. Thanks largely to the efforts of a man named Felix Morales, now 78, it was the first of a half-dozen local stations to broadcast in Spanish. In 1931 Morales moved to Houston and opened a funeral home. To advertise his services, Morales, an amateur musician, began buying air time on KLVL, then centered in Pasadena. In 1950 he bought its license and opened the present studios in the metal building at the corner of Canal and North Paige in El Pasillo. Apparently out of the kindness of his heart, he originated the program called Yo necesito trabajo [I need work], which today continues to provide job leads to the unemployed.

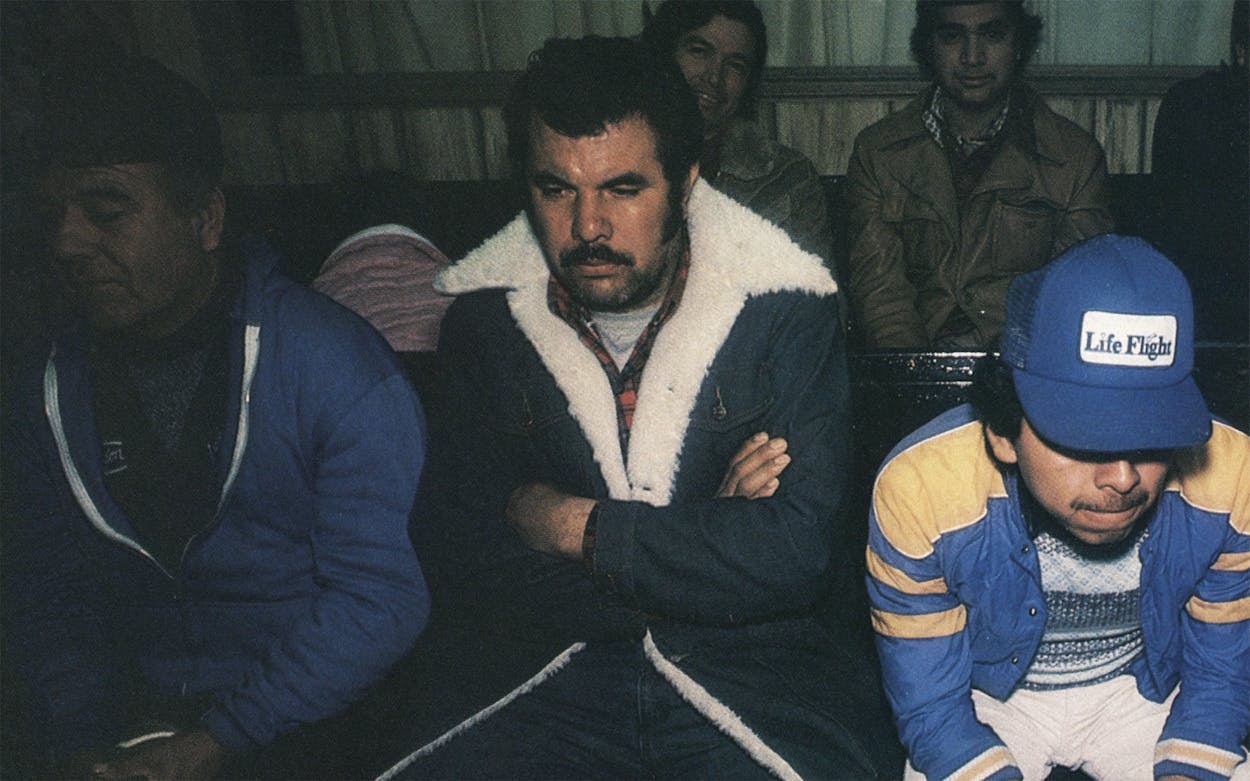

Early one morning I went to the station, where a crowd of men and women were already waiting to take part in Yo Necesito Trabajo. Shortly after we arrived, the doors opened. We went inside and took seats on one of a dozen black benches. Before long nearly a hundred people filled the room, and some had to sit on the floor.

At ten o’clock, the program began. “Courteous and genteel listeners,” the announcer said in Spanish, “at this hour we bring you the program Yo Necesito Trabajo, as we do every day from Monday through Friday, with the intention of alleviating unemployment. We hope that we will be able to assist the great number of people who are visiting us today in our studio. We extend an invitation to businessmen, contractors, and housewives to seek employees through our program. You only need call us if you need workers. Those in need of employment must come to our studios.” Then he began reading a list of jobs. “A woman is needed for light domestic work and to care for a child—salary eighty dollars a week. . . . A baker is needed with experience in cooking Mexican bread—salary by personal arrangement. . . . Nine waitresses are needed for a club—salary by personal arrangement.”

When the program ended at ten-fifteen, those of us who wanted to ask about particular jobs lined up at the receptionist’s desk. She handed us slips of paper with the employers’ names, addresses, and telephone numbers. Outside the studio, people stared at their slips, asking companions for directions to job sites and looking at bus schedules. Some stood around for a few minutes with their hands in their pockets, dismayed because there was no job suitable for them.

Five of us were referred to a job as painter’s helpers. One of the group had a car, and he charged three of us $5 each for a ride to the job site. The fourth man, who said he was Peruvian, rode for free; he told the driver he didn’t have any money, and he looked like he was telling the truth. The job was at a new apartment building in the Westheimer area. Fifteen men were working there, painting exterior trim. It seemed to me that there were already more men on the job than were needed.

The painting contractor was an Anglo who didn’t speak to us. We dealt with his foreman, a Mexican American. He promised to pay us $5 an hour, but after the first hour’s work, I was nearly finished with the panel assigned to me. The Peruvian was nearly finished too. The foreman told us to come down form our ladders, said that we didn’t know how to paint, paid us $5 each, and sent us on our way. The Peruvian, a short man with Indian features, was dressed sloppily and wore cowboy boots too big for his feet. As we walked along Westheimer looking for a bus stop or a place to eat, he kept repeating, “¡Qué malo nos trata la vida! ¿Verdad, no?” (“How badly life treats us! Isn’t that so?”) He continued his monologue as we went into a Chinese restaurant to take advantage of a $2.60, all-you-can-eat lunchtime special.

While we were eating, he told me that six months earlier he had left Peru and illegally entered Central America. The Sandinistas, he said, jailed him for fifteen days, and then he headed for Mexico. For a month he worked as a brickmason in the state of Veracruz, then took his savings and boarded a bus for Matamoros. Four times he crossed the Rio Grande by himself and caught a train going north. Immigration agents caught him every time, and every time he swore that he was Mexican and was returned to Matamoros. Not until his fifth crossing did he succeed in reaching Houston. Once in the city, he made friends with Mexicans in El Pasillo who offered him a place to stay until he found a job. He had been there three months without finding any steady work.

“I’m going to go to Spain,” he told me toward the end of the meal. “Over there people are more civilized. Here the people are ignorant. They don’t know that to get by, a man needs help.”

I wasn’t tempted to accompany him on his voyage to Spain, yet I recognized a certain tortured logic in his plan. It was the logic of the wetback, which said that if luck turned bad where you were, things would be better somewhere else. The idea of going to Spain also had practical merit—in Spain everybody speaks Spanish. But I’m Mexican, not Peruvian, and the biggest advantage that Texas offers me is that it’s only a bus ride from home. If I decide to give up my venture in Norteamérica, I can soon be back in Oaxaca.

For several mornings after my unsuccessful trip to KLVL, I stopped for an hour or two outside the El Charro, a nightclub next door to the radio station. There, from five in the morning until well past noon, people waited for chance jobs. Small-time contractors and maintenance foremen stopped at the corner, looking for laborers. Workers were hired for temporary jobs, like carrying shingles up flights of stairs or ladders to professional roofers. Strong men could earn as much as $40 a day carrying shingles, but most didn’t have the stamina to stay at it for long. Men on the corner said that sometimes employers who picked them up there promised to pay them on Fridays—but didn’t show up when Friday came around. They also said that good jobs, plentiful on the corner during the oil boom, were rare today. The only brisk hiring period in 1983, for example, came in the wake of Hurricane Alicia, when cleanup and repair gangs cruised Canal looking for laborers. Still, a dozen men did ride off in pickups with foremen each day, and two or three didn’t come back because they had found jobs that lasted for weeks or months.

To get a steady job, a wetback has to have nerve as well as luck. He’s got to get around the law, for one thing. Though it is not illegal to hire wetbacks, there are laws requiring employers to provide Social Security coverage for workers, and the Social Security Administration won’t issue cards to illegal aliens, as it once did. To bypass the requirement, most undocumented immigrants draw Social Security numbers out of thin air. But on the advice of one of Abel’s roommates, I decided to try what I thought was a better gambit. I went to buy a counterfeit Social Security card.

In a neighborhood car lot I found the man I had been told about—a Mexican American with long black hair and coveralls. He was half hidden beneath the hood of one of the cars he had for sale.

“I need a Social Security card,” I said.

“Have you got the number?” the man asked, without looking up from the car’s motor. I told him that I didn’t have one. “Ah, you want me to make up a number for you. Is that it?” He hesitated, then said, “Just wait. I’ll be finished in a minute.”

Half an hour later he took me into his little office. Among the rags and tools was a small desk across from a television set. He sat down, took a card from a box, rolled it into his typewriter, and asked my name. He typed it and a nine-digit number onto a white card with blue printing on both sides. I paid him $5 and went away pleased, thinking I had purchased a perfect counterfeit.

I later learned that it was doubly false. I wanted the card so that I could deceive my employers, but it deceived me. The front showed two pillars, outlined in blue, with an arched line running between them, just like a legitimate card. Above the arched line in bold letters were the words “Social Security,” in the same typeface used on genuine cards. But underneath the arched line in tiny letters were the words “Not Issued by the United States Government.” On the back, instead of a listing of occasions when the holder should contact the Social Security Administration, my card carried three disclaimers. One of them said, “No harm or fraud is planned or intended, toward any country, company, or person.”

The Company Gives and the Company Takes Away

After two months in Houston without a steady job, I began to lose hope; I decided to try my luck in another town. A friend suggested that I go to San Antonio. Elva,* a woman who had been a close friend in Oaxaca, was living there, he said, and she would probably be willing to help me.

From the minute I got off the bus, San Antonio seemed more hospitable to me than Houston. Almost everybody I talked to spoke Spanish, and Hispanics were not a minority, especially in the southern and western parts of the city.

I found Elva working in a store where she was paid $3.75 an hour to package corn tortillas, tostadas, and taco shells. Elias,* her husband, who spoke some English, earned as much as $300 a week as a waiter. Their two children, a nine-year-old girl and a five-year-old boy, attended public schools and were bilingual. Elva and Elias owned a four-year-old car, a black and white television, a stereo, and bedroom furniture. They lived in an old but well-maintained wooden apartment building on San Antonio’s Hispanic West Side. Their rent was $200 a month, which was probably $100 less than the same quarters would have cost in Houston. Elva and Elias slept in the apartment’s only bedroom; the children slept in the living room. When I arrived, Elva offered me one of the single beds in the living room. The children doubled up in one bed to make room for me.

When I started looking for work in San Antonio, I didn’t feel that I had to look for casual jobs at corners like the one in Houston. San Antonio has had illegal immigrants ever since restrictions were imposed on Mexican immigration more than fifty years ago. Businessmen in town routinely hire Mexican workers, knowing that they don’t have immigration papers. In Houston, Mexicans work when there is a labor shortage; in San Antonio, we have always been a part of the permanent labor force.

Not far from Elva’s apartment I found a woodworking shop and decided that I’d like to work there. I had worked for a while as a carpenter in a little shop in Oaxaca, building chairs and tables by hand for customers in the village. With luck, I figured, I could learn skills that would serve me well if I ever returned to my hometown. I went to the shop and asked for a job. A young Mexican American woman behind the counter said that the company did not need workers, but she wrote down my telephone number at Elva’s. Three days later she called to tell me to present myself for work. I arrived at the shop and, after a short wait, was introduced to the owner, a light-skinned Mexican American man with brown hair. He was dressed in khaki pants and a T-shirt with the shop’s name and emblem and, across its back, his own name.

“This is the boy I talked to you about,” the secretary said.

“Are you really a carpenter?” the owner asked me.

I said that I was but that I’d never made the pieces that were made in his shop—cabinets, desks, and windows, for example—nor had I worked with power tools. “Your experience is valuable, and you can learn to use power tools,” the boss said. “Let my secretary write down the information about you, and I’ll meet you back in the workshop.”

I gave the secretary the information she requested, including the Social Security number Elias had helped me concoct. I claimed three dependents because Elias had told me that wetbacks couldn’t collect income tax refunds, and I had to make sure that my withholding was minimized. The secretary told me that I would be paid the minimum wage, $3.35 an hour.

The workshop was a big place, about 25 yards wide and 50 yards long. Inside were two circular saws, a drill table, two band saws, a big sanding machine, two lathes, saws for cutting at angles, drills, polishers, planers, and other devices. Big stacks of pine, oak, ash, cedar, poplar, and birch sat on shelves made of steel tubing that lined the walls. Eight men were at work, some at machines, others standing at big wooden tables. The machines emitted sharp sounds and filled the air with clouds of smoke and sawdust.

In a few days my new job was a routine. I came to work promptly at seven-thirty each morning; the secretary noted entry and exit times for all the workers. My first duty was to collect the trash. Then I selected pieces of scrap wood that might still be of some use and stacked them on shelves. At eight the master carpenters arrived, and I spent the rest of the morning helping them. They usually had me sand pieces of furniture that they had finished building. After lunch I swept again, then usually returned to sanding. Sometimes there were small repair jobs for me, such as dismantling and mending doors.

After I had been on the job for a few days, the foreman told me to saw some wood and to ask in the office for a measuring tape. When I asked for the tape, the secretary said she would sell it to me. I told her that I didn’t need it for some project of my own but to saw wood for the foremen.

“That’s why I’m going to sell it to you,” she said.

“Well, then, sell me ten of them,” I said. I thought she was joking.

“Which do you want?” she asked. “The one twelve feet long or the one sixteen feet long?” I took the twelve-foot tape. The day after payday the secretary called me into the office and said that I owed $10 for the tape. I told her that I hadn’t brought money with me, and we agreed that its price would be deducted from my next paycheck. “What the heck?” I thought. “The company gives, and it takes away.” After all, when I had been there two weeks, the boss gave me a company T-shirt.

Two or three weeks later, while I was working with a circular saw, I accidentally cut the tape in half. I told the secretary, and she offered to sell me another tape at the same price as before. This time I went to a hardware store and found that a 24-foot tape cost only $4.50.

That was the beginning of my disillusionment with my job. A few weeks later I witnessed an unfortunate accident. Arturo,* another Mexican worker, sliced off the tip of his right thumb while cutting some molding on a circular saw. He went home early in the afternoon. The next morning, he didn’t show up, and the owner told me that I could do the job. Arturo, he said, had cut himself on purpose to get a few days of rest with pay.

“¡Carajo!” he said. “That’s the way Mexicans are. That boy has always been that way. You’re always supposed to have your left hand in front when you work on the saw. So how could he cut his right hand? It was intentional,” he assured me.

A few hours later Arturo came into the shop. He asked me if I was the one who had told the owner that he cut himself on purpose. “The boss invented that story so he wouldn’t have to pay you for your time off,” I told Arturo. But I shouldn’t have said anything within the hearing of Ruperto, the boss’s favorite employee.

Though I’ll never know for sure, I think that Ruperto told the boss that I didn’t believe his story about the accident. Ruperto also probably told him that I didn’t like buying my own measuring tape, that I didn’t believe my hours were always recorded faithfully, and a good many other things I had confided to him, as workers do among themselves. I know that someone carried my opinions to the boss, because not long afterward the boss began to harass me. One afternoon he told me, in front of everybody, “Lately your work has to be done twice, and that doesn’t sit well with me at all. I thought you were a master carpenter, and now I see that you don’t know anything.”

Later that day I told Don Pancho,* an older worker from Oaxaca, that if the harassment continued, I was going to quit. Don Pancho had survived in the United States since 1964, and his opinion mattered to me. “Well, you can quit,” he said, “but I wouldn’t do it if I were you. Here, if nothing else, you can learn things that will help you if you go back home. Besides, when we come to this country, don’t we come so that they can exploit and humiliate us? Don’t we come so they can screw us? We want to save money to take home, don’t we? We know that we have to endure.”

Don Pancho advised me to stay at least until I showed everyone that I could do good work. I decided to follow his advice. But a few weeks later—after proving to my own satisfaction that I could do good work—I quit. Living with Elva and Elias, I had saved enough in two months to pay off the debt to my friend for my coyote. But I haven’t paid him yet. Instead I’m thinking of paying a coyote to bring my wife to me when she finishes school. I think I’ll have her go not to San Antonio but to Los Angeles, because I have friends there, people my own age, from my own village. They all have jobs and can help find work for me and her—there aren’t any jobs in Mexico today, for college graduates or anyone else. And the airlines are having a sale. For $100 I can fly from San Antonio to the West Coast. From what my friends tell me, I’ll have a new job by the time the coyote gets there.

- More About:

- TM Classics

- Mexico

- Longreads

- Houston