This story is from Texas Monthly’s archives. We have left the text as it was originally published to maintain a clear historical record. Read more here about our archive digitization project.

Hallie Stillwell was wearing a Western-style plaid blouse and a denim skirt when I went to see her last July, the kind of clothes she had worn for years, and that made it easy to imagine she was about to get up and walk around. She was wearing pink terry cloth slippers instead of shoes, though, and she was sitting back with her legs up on a wheeled bed, and it had been a long time since she had walked on her own. I was visiting her at the nursing home where she lived out the last ten months of her life, a brick building on a hill in Alpine. Stillwell was 99 when she died, on August 18. In the weeks before my visit she had retreated into an interior world. She rarely spoke anymore, even to family members, and she had nothing at all to say to me. I wondered what she was thinking as we sat together under a tree in a garden behind the main building, looking out at one of those burning West Texas days: the striped red hills, the spiky sotol plants, the bare sky.

She loved that land. It had always comforted her to look at it. When Hallie married and first moved to the Stillwell ranch, down near the Big Bend, she used to sit outside to regain her composure after a long day, particularly if she had failed at some task, disappointing her husband, Roy. “Soon after the evening meal,” she wrote in her autobiography, “as I was sitting on a rock, looking into the far-away beautiful mountains in Mexico and enjoying the lovely evening shadows so typical of West Texas at dusk, my emotions were calmed and I felt peace and happiness.”

When that book, I’ll Gather My Geese, was published six years ago, it confirmed Stillwell’s status as a living Texas icon. She became emblematic of the Big Bend region of West Texas, a person who epitomized that part of the country—or rather, what that part of the country had once been like. Stillwell reminded people of a lost time—the frontier era—and at this safe remove from its actual hazards, those days seemed like a particularly romantic time. In fact, Stillwell never claimed that she was a living symbol of anything, let alone West Texas in its wild and woolly days. When she arrived at the Stillwell ranch in 1918, she was a stranger, uncertain of the rules and constantly transgressing them. In her book Old Texas appears in the figure of Roy, a cowboy to the bone, the embodiment of what the Big Bend once was. Hallie was many things throughout her life: a schoolteacher, a rancher, a newspaperwoman, a beauty parlor operator, a justice of the peace. Some of her choices, such as getting into newspaper writing, were considered odd in West Texas ranching country, where discretion was prized above communication. It was her outsider status that enabled her to write about the place so well.

Hallie Crawford was born in Waco in 1897. Her father had a hard time staying put, and over the next twelve years, the family made five moves, stopping in various West Texas towns and then homesteading in the New Mexico Territory. The Crawfords moved to Alpine for the school facilities, among the best in the region. One of Hallie’s schoolteachers was J. Frank Dobie, and her daughter, Dadie Potter, believes that Dobie probably inspired Hallie to write.

Hallie went on to become a schoolteacher herself; in 1916 she began teaching in the border town of Presidio. Pancho Villa’s army had recently captured Ojinaga, and Presidio was full of refugees when Hallie arrived. Her parents, worried, had urged her not to accept the job, but she did what she wanted. “I found the days hot, the sand deep, the Mexicans strange, and the U.S. soldiers curious about an Anglo girl moving there,” she wrote in her book. “There was only one other white girl there . . .” Though she took refuge in the federal fort when Villa was rumored to raid, the greatest threat Hallie faced came from the U.S. troops stationed along the border; one afternoon she was chased by two drunk soldiers.

The following year Hallie taught in Marathon. It was there that she met Roy Stillwell, a rancher who had grown up in Mexico, where his father had owned land. Stillwell owned a 22,000-acre ranch 46 miles southeast of Marathon, just northeast of the land that, decades later, would become Big Bend National Park. In 1918, after a courtship that consisted of automobile rides, picnics, and midnight serenades performed by a blind Mexican guitarist Stillwell had hired, the two became engaged. Hallie was twenty, Roy was twice her age, and he was known to drink and gamble. Again Hallie’s parents opposed her decision, so she and Roy eloped.

Hallie’s move to the Stillwell ranch transformed her. She had always been an avid rider, a good shot, and a girl who lived to please her father rather than her mother, a Southern lady who thought Hallie’s tomboy ways made her a fright. Even so, she was not prepared for ranch life. First, there was the ranch house itself: “I really hadn’t expected much but I was somewhat surprised at its size, one room about twelve feet by sixteen feet.” Upon her arrival the three cowhands moved out into the barn. No woman had stayed at the ranch before, and they viewed the development with disdain. Hallie took the cool reception as a challenge, deciding to prove herself useful. She didn’t have much of a choice—her husband considered it unsafe for her to stay at home. He expected Hallie to ride with the cowhands. When she showed up the first morning in a riding skirt, Roy said she would spook the horses and insisted she wear men’s clothes. “I found out quickly that I was to live like a man, work like a man, and act like a man, and I was not so sure I was not a man when it was all over.”

Learning to be useful was complicated by the fact that Roy, an often-difficult man, seldom gave explicit directions. “For cowboys, the life of a ranchman is nothing to brag about, their problems are nothing to discuss with other people, and their business is very confidential,” Hallie wrote. “[F]ew have much to say, and most expect others to know what they are thinking at all times. Roy was certainly this type of person. This made life on our ranch somewhat complicated at times.”

Motherhood changed Hallie as much as the ranch did. Married life had seemed an adventure, a liberation from the constraints of her parents. But once she discovered she was pregnant in 1919, Hallie realized her days of independence were over. Her first child, christened Roy but known as Son, weighed twelve pounds and was born after 48 hours of labor, endured without anesthesia. His arrival transformed the atmosphere of the ranch house; the cowhands, who had been so distant to Hallie, melted around Son. Two more children followed, Dadie and a second son named Guy. The cowboys finally warmed to Hallie.

Over the next twenty-plus years, Hallie tended to the children, worked alongside Roy, and watched the children work alongside him as well. The ranch was plagued by a series of hardships. Everyone fell sick during an epidemic of Spanish influenza; Roy got tuberculosis; Son left to fight in World War II; a dust storm that looked like a crawling blanket smothered the ranch; drought choked the land. Hallie took it upon herself to modernize the ranch—usually over Roy’s objections. One of the first improvements she wanted to make was to install running water in the kitchen. Roy, stubborn in his old ways, refused to install the sink, saying it would just get clogged up. Finally one of their nephews did the work. When Hallie wanted to build a bathroom, Roy balked again; this time she did the work herself. Later on, when a man drove up in a pickup carrying a gleaming new gas-burning refrigerator that Hallie had ordered, Roy became apoplectic.

“How is everything, Roy? Had any rain?” the refrigerator salesman asked.

“Nope. It is hotter than blue blazes and dry as hell,” Roy shot back, “and you can take that thing right back to Alpine.”

Like any true cowboy, Roy considered appliances unnecessary and a sign of going soft. Hallie was a generation younger and more open to change. But she wasn’t soft. In 1948, just as Texas was sinking into the grip of its most prolonged drought on record, Roy set off for town for a load of hay. Hallie thought of going with him, but she was watching her granddaughter at the time. Instead, she asked him to mail some letters and to bring her two loaves of bread.

“I later heard that Roy made the trip into town safely, got his hay, ran my errands, and made a last stop at the general store,” wrote Hallie afterward. He also visited their house in town to look in on Dadie.

“I don’t think your mama and the boys realize how serious this drought is,” he said to her.

“Oh, yes, they do,” Dadie told him. “Mama just always tries to cheer you up. She realizes how bad it is. She knows we’re in for rough times.”

Roy’s truck overturned on the way home. When Hallie got to the scene of the accident, he was unconscious, but she thought he would be all right. It never occurred to her that Roy, who was so tough and had weathered so much, might be fatally hurt. But doctors discovered massive internal injuries, and he lasted only 24 hours more. In the aftermath of Roy’s death, the drought worsened, and Hallie managed to hang on to the ranch only by leaving it in the hands of her sons and taking on a series of other jobs.

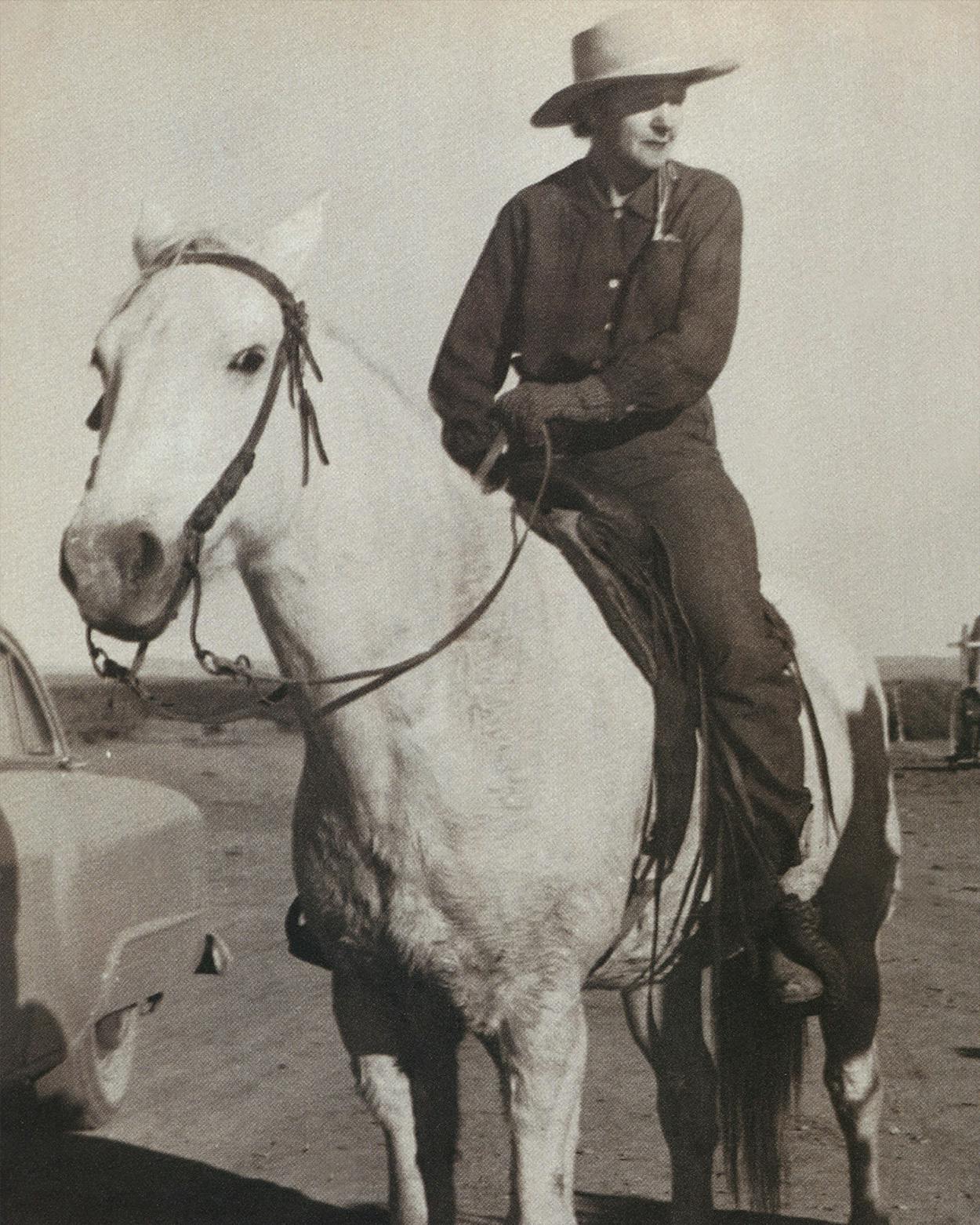

The job that she held the longest, and that she seemed to find most satisfying, was that of justice of the peace in Alpine. From 1962 to 1977, Hallie drove all over Brewster County, the largest county in Texas, performing marriages, serving as the coroner, and judging misdemeanor cases. That job, along with her Ranch News column, which she began writing for the Alpine Avalanche in 1955, made her a local celebrity. Finally, when it was clear that the cattle business was becoming less and less profitable, in 1969 Hallie opened a general store and an R.V. park on her property just six miles from the northern entrance to Big Bend National Park. “That was one of the smartest things she ever did,” says Dadie. In a sign of the changing times, the store and park soon generated more money than the rest of the ranch. To the campers who arrived every year, Hallie became something of a tourist attraction herself. In 1991 Dadie opened a museum called Hallie’s Hall of Fame, which features exhibits like the Colt .38 pistol Hallie carried in Presidio, photographs of Roy on a white horse named Red, and the crude bedroll they once shared.

Toward the end, visiting Hallie was a different experience. She stayed at the nursing home in Alpine after a stroke made it extremely difficult for her family to take care of her. As we sat outside watching the hills rise beyond Alpine, I told Hallie that I was reading her book, but I got no response. I tried several other openings; all failed. Eventually Hallie closed her eyes and dropped her head. I began to think that visiting Hallie hadn’t been a good idea. She was old, and I should have left her in peace. But I had hoped that by meeting her in person, I might get a glimpse of the individual behind the folksy legend displayed in the Hall of Fame.

Just then a small, spry woman with short white hair and sporting Wrangler jeans, a Resistol hat, and a cane, stepped up. “Hallie? Good morning! Good morning! Hello, darling!” she yelled. “I’m Faye, Faye Yarbro. We’ve had a lot of good times together!” Yarbro, a funny, salt-of-the-earth retired schoolteacher, had known Hallie for years, but she believed that Hallie no longer recognized her. This did not faze her. She went on chattering at top volume, and Hallie soon brightened visibly. “I found a picture of you,” announced Yarbro. “It was taken when you came and talked to a group of retired teachers, and you told about being in Presidio. You had a pistol that you put in your teacher’s desk. Sometimes Pancho Villa would raid over on this side, and the soldiers would come and take you to that fort.”

The significance of Yarbro’s words struck me later. I had gone to see Hallie hoping she could uncover some original truth hidden inside the myths of her life, and instead I found myself listening to somebody tell those stories back to her. I realized then that Hallie was almost gone—not just that she was losing her hold on life but also that we are losing the reality of what her life once meant. There is no stopping the accretion of myths about her; a community hungers for legends and heroes. She knew West Texas when it was young. She knew Roy when he was a cowboy, when he raced horses and roped cattle and they slept under the stars on a bedroll. It did not matter that she was really more representative of the New Texas than the old one. The store and the campground, strangely public enterprises to mix with the solitary occupation of ranching, are exactly the kind of accommodation that ranchers all over West Texas are having to make these days. One can only imagine what Roy would have said about it all.

- More About:

- Texas History

- Obituaries

- Marathon

- Alpine