This story is from Texas Monthly’s archives. We have left the text as it was originally published to maintain a clear historical record. Read more here about our archive digitization project.

Bob Wade’s art—outrageous, outlandish, but rarely outshone—definitely imitates his life. Eccentric even by artists’ standards, Wade, better known as “Daddy-O,” specializes in gargantuan, do-my-eyes-deceive-me artworks; his diverse subjects include jackalopes, Pancho Villa, and the United States map. In Daddy-O: Iguana Heads and Texas Tales, due out this month from St. Martin’s Press, the 52-year-old Santa Fe–Dallas resident relates the often improbable but always entertaining tale of his career. Wade is surely the only artist to incorporate Lee Harvey Oswald’s autopsy photos into an installation and to be booed by the anything-goes Mardi Gras mob in New Orleans.

The son of a hotel manager, Wade was born in Austin and grew up all over Texas—El Paso, San Antonio, Waco, Beaumont, Galveston. The Old West myths and border-town culture he absorbed throughout his childhood stoked (some would say warped) his artistic inspirations from the get-go. His interests range from circus freaks to hot rods to velvet paintings; his techniques, from scavenging vintage Western souvenirs to rigging found-object assemblages (art lingo for “things made out of junk”). Some of Wade’s artistic curiosities are, for him, fairly simple undertakings: a bullet-riddled, school bus–yellow delivery truck (dubbed “the Bonnie and Clyde Mobile,” it provoked catcalls and hisses at the 1982 Mardi Gras); a four- by ten-foot hand-tinted photo of Waco cowboys (which eventually hung over Ann Richards’ desk when she was governor). Most projects are far more elaborate, such as a three-hundred-foot-long, three-dimensional U.S. map complete with mountain ranges, highway billboards, and a sculpture for each state (Texas: oil well; Maine: lighthouse; Iowa: corn).

Wade’s art is of the people, by the people, and for the people. For one thing, his purely Texan, bigger-is-better philosophy often translates into huge construction projects requiring the supervision of dozens of helpers—welders, upholsterers, taxidermists, electricians, glass blowers, and many more. (“To some extent I operate like Tom Sawyer,” he notes. “If somebody stops by, I immediately put him to work.”) For another, his pieces provoke what he terms “gasp reaction”; word of mouth inevitably makes them landmarks and must-sees. On these pages are a quintet of Wade’s most notorious projects, with never-before-seen sketches and pictures from his personal scrapbook that trace the evolution of each sculpture from conception to completion. Muses Wade in his bio: “Art critics love to ask, will [this art] survive the test of time? [To hell with] the test of time . . . my art [has] gone through fires, tornadoes, court battles, drunken cowboys, squatters, chainsaws, gypsies, theft, tourists, and me.”

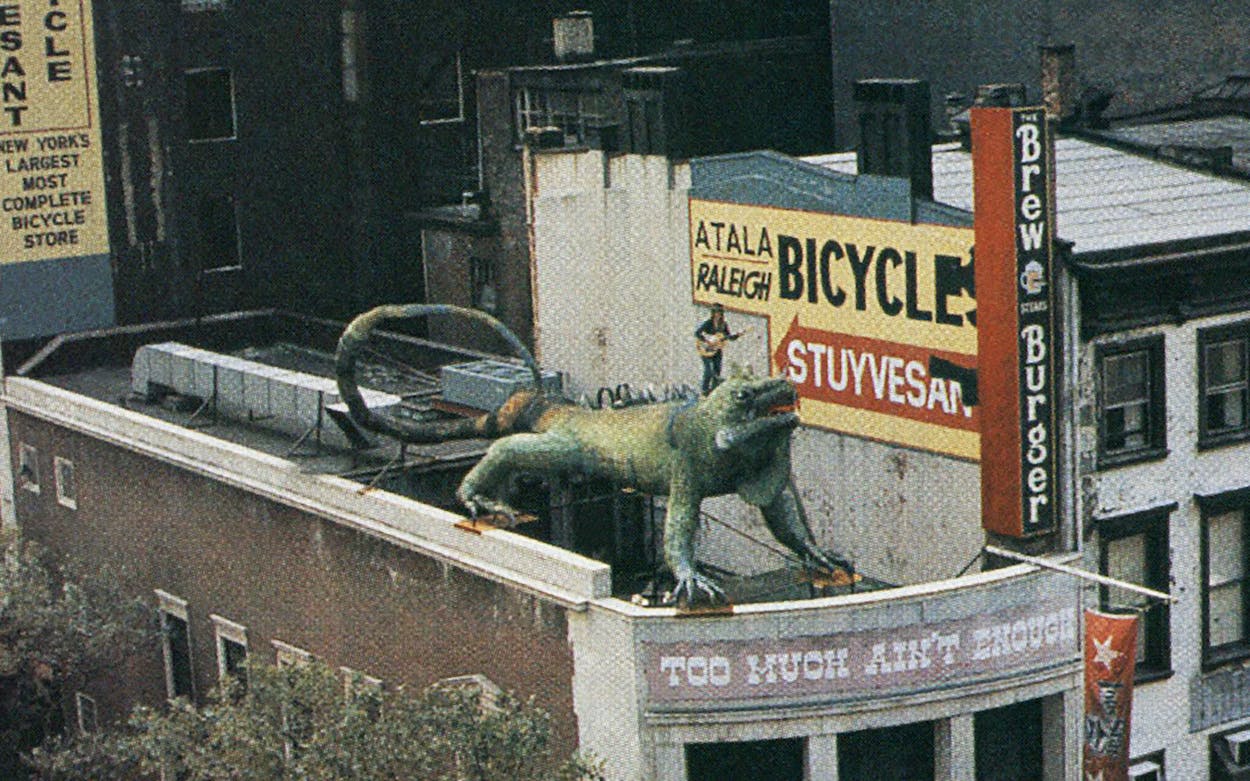

The Giant Iguana

Wade’s forty-foot iguana is his most famous work. Originally exhibited in 1978 at Art Park, a summer celebration of outdoor sculpture in Lewiston, New York, the modular lizard was created piece by piece for ease of assembly. Wade and his workmen stretched wire mesh over an aluminum framework, sprayed quick-drying urethane foam to flesh out the body, then spray-painted the skin a vivid green and added hand-blown glass spheres for eyes. At a friend’s suggestion, Wade called the Lone Star Cafe to propose relocating his personal Godzilla on top of the New York City restaurant. The owners were bewildered but game, and the rooftop, propitiously, was the perfect size. The placement of the sculpture immediately ignited a prolonged citywide controversy: Was the iguana a sign or a piece of art? The matter wound up in court, where a judge—expressing his fears for the Statue of Liberty—ruled in favor of the Lone Star Cafe. Wade went on to bedeck the iguana with a hefty jack-o’-lantern for Halloween and antlers and a shiny red nose for Christmas.

The Texas Mobile Home Museum

In 1977 Wade was asked to participate in the tenth Paris Biennale at the Musée d’Art Moderne. As he recalls in his book, “Maybe Paris was ready for a freaky traveling Texas roadside museum. It was time for another Daddy-O art adventure. It all started with the gathering process.” Inside a funky aluminum trailer from the forties, Wade assembled a two-headed calf, a mounted bucking bronco (placed upside down), a pair of fourteen-foot fiberglass Longhorn horns, stuffed armadillos, and plastic bluebonnets. On the outside he added more horns, lengths of thick lasso-style rope, chrome-plated barbed-wire fender skirts, cow skulls, and 150 hand-tooled leather belts; blaring Waylon-and-Willie tapes were a final, auditory touch. The “white-trash horror show” earned a prime spot near the Eiffel Tower. “From that moment on,” Wade writes, “a throng of French art fans always surrounded the trailer.” Today the automotive artwork, vandalized and deconstructed, still languishes in Paris. According to Wade: “At last count, the tab [for storage] was somewhere over $10,000.”

The Biggest Cowboy Boots in the World

In 1979 Wade’s Brobdingnagian boots capped an awesome three-year burst of creativity. Using visual aids such as a cut-and-pasted mock-up of the boots-to-be on the proposed site in Washington, D.C., the artist hawked the project to a nonprofit art group: “Another monumental work of art by Bob Wade, native Texan, June through October, four blocks from the White House on an empty corner lot, 12th and G at the Metro Center, forty feet high, thirty feet long, heel to toe, simulated ostrich skin, high tops with collars, pointed toes, fashion heels with caps, elaborate stitching, formed by spraying urethane foam over tubular steel and wire armatures, dismantled for easy transport.” Today the boots stand tall outside San Antonio’s North Star Mall, where thousands of shoppers and passersby admire them weekly. Tourists enjoy posing in front of them for an everything’s-bigger-in-Texas photo souvenir. Once a homeless man took up residence in the left boot, and his campfire smoke alarmed the owners, who thought their pricey sculpture was on fire.

The Musical Frogs

The most widely traveled of Wade’s creations—so far—the terpsichorean amphibians and their four musician buddies were inspired by the mounted souvenir frogs Wade recalls buying on trips across the border. They first graced the top of the short-lived Tango nightclub in Dallas in 1983, where they sparked a second sign-or-art debate. (Art again prevailed.) The sextet was later moved to Carl’s Corner, a humongous truck stop in Hillsboro. “They became something of a landmark,” Wade writes. “Besides [the] regular trucker clientele, parents driving from Dallas to Austin to visit their kids at college or vice versa, as well as families with station wagons full of whining kids, would all pull off the road to see the frogs.” In 1989 the frogs—temporarily parked next to the swimming pool—were the only fixtures to escape when Carl’s Corner burned to the ground. Now rebuilt, the truck stop still boasts three of the gaudily painted critters; the rest have moved to Houston, where they adorn the bar inside the Chuy’s restaurant on Richmond Avenue.

Smokesax

Sax sells. At least that was what two Houston entrepreneurs discovered in 1992, when they commissioned Wade to create “a big, elaborate, razzle-dazzle sculpture” in front of their Billy Blues barbecue and blues joint. Pondering the assignment, Wade decided to tackle a supersized saxophone: “It was so complex a design that unless you were a repairman, you couldn’t even draw one perfectly, which lent to the sculpture’s abstract potential. This in turn left lots of room for interpretation and design, which left a lot of room for Daddy-O.” The sax was fashioned from Wade’s weirdest junk assortment yet—an entire Volkswagen bug, turned on its back, for the bottom curve of the instrument; hubcaps and stainless-steel room-service tray lids for stops; a surfboard and a beer keg for the mouthpiece. The seventy-foot sax enabled Wade to fulfill a lifelong goal—to construct a piece of public art taller than Big Tex, the 52-foot cowboy who looms over the entrance to the State Fair of Texas. Says Wade fondly: “I still think of [the sax] as my second most permanent erection.”

- More About:

- Art

- TM Classics

- Sculpture