This story is from Texas Monthly’s archives. We have left the text as it was originally published to maintain a clear historical record. Read more here about our archive digitization project.

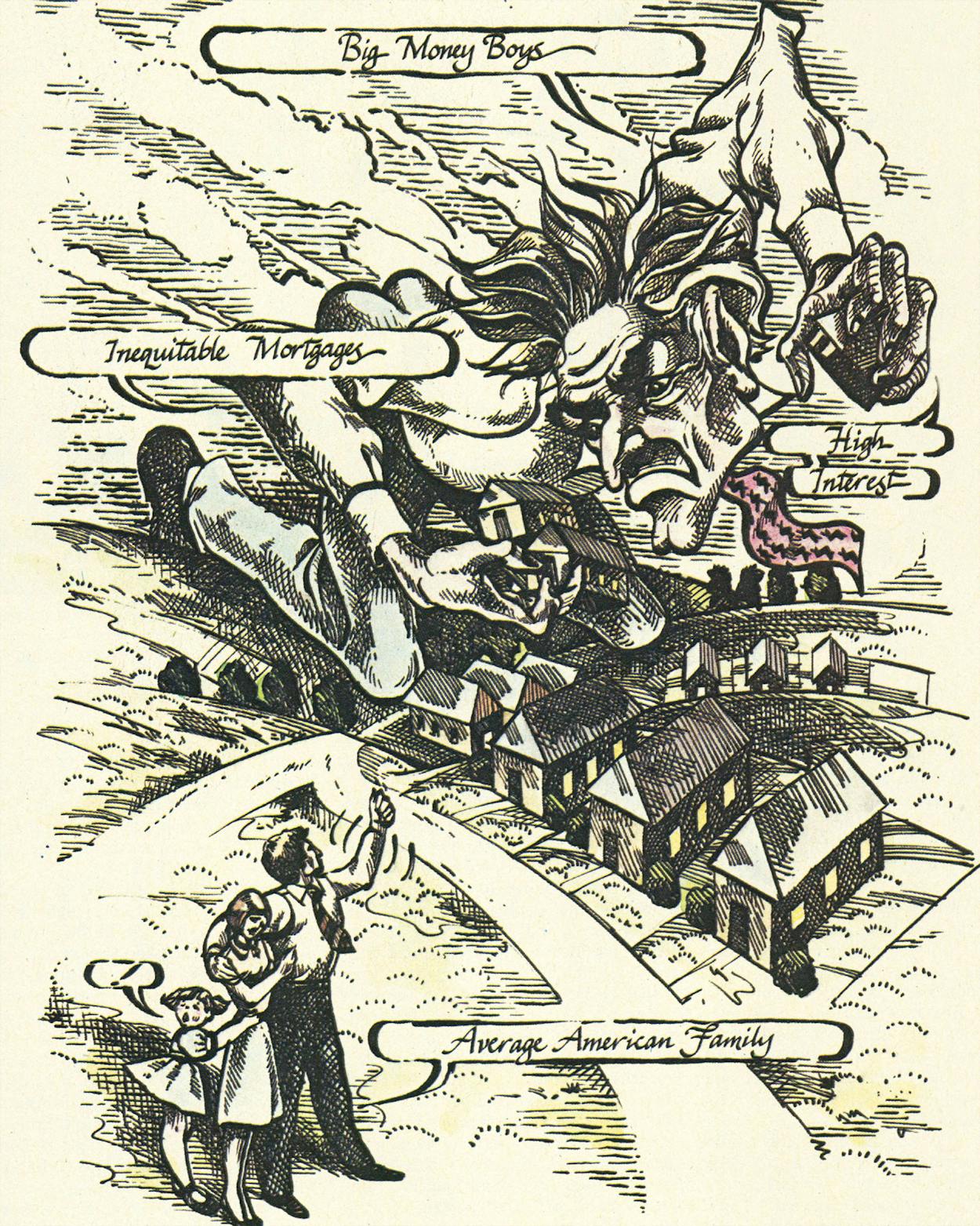

Want to buy a house? Great idea. The residential landscape from Texarkana to El Paso is littered with For Sale signs; the classified ads are crying for buyers. What kind of house? Let’s say an average house—three bedrooms, two baths, the ordinary run of appliances, nothing special in a nothing-special neighborhood. If the neighborhood is in Dallas you can pick up your average house for about $78,000; in Houston it goes for $82,500. Those are the hottest markets, but all over Texas house prices have doubled in the last five years, along with mortgage interest rates. Most first-time home buyers are being shut out of the market, or else they’ve taken a look at what they can afford and decided to pass. It’s the worst time in decades to buy a house. It may also be the worst time not to.

Is it that bad? It’s worse. When buyers can’t buy, sellers can’t sell, lenders can’t lend, and builders can’t build. The building industry slows down, creating a housing shortage, which drives prices up even in a stagnant market. But prices aren’t the only problem. Interest rates make a bad situation worse. Four years ago, when mortgage interest rates were 9 per cent, people could qualify to buy homes at two or three times their annual incomes. Now, with rates in the teens, buyers are qualifying for little more than one year’s salary. Lenders look at large monthly expenses like car payments and utility bills when considering a loan application. It’s a shock to most people how little home they can afford.

Got a good job? Let’s say you’re making $30,000 a year and you’ve got $5000 in the bank to handle the down payment and closing costs. If you had made that salary four years ago, you would have qualified to buy a $90,000 house, which, in Houston, might have been a substantial two-story brick house on a shaded residential street. Now that same house is selling for $150,000, and realtors roll their eyes if you want to see it. A lender will figure that you take home around $1800 a month after taxes and will qualify you for payments of about $550 a month. Congratulations, you’ve got yourself a $47,000 mortgage. It may take some adjustment, but you’ll come to love your new home—a shotgun cottage on the outskirts of Pasadena.

So you bought your house three years ago, before the interest rates went wild, but you’d like to trade up? Your original mortgage was for $50,000 at 9 per cent interest, and you’re going to make a killing when you sell at $100,000. The house you have your eye on is a little larger and in a nicer location, priced at $150,000. The lender says he wants every cent you make from the sale of your old home before he’ll give you a mortgage for the difference. You were paying $402.31 a month, not including taxes and insurance, on your old house, but the payments on the new one, even with all that equity, are going to be $1112.30. At least you’ll be getting a nicer house. Suppose you had bought a house for $100,000, the price at which you sold your old home. Even with more than $56,000 to put down, and the resulting smaller mortgage, your monthly payments would have increased more than $100 a month. Closing costs and brokers’ fees add even more to the cost. These days, most people are finding out that the only way to make a killing in real estate is to get out of it.

The problem is that no one can. We all have to pay for shelter. But we’ve never had to pay like this. In 1970 housing took 18.3 per cent of the average American’s monthly disposable income; today that figure is 33 per cent and climbing. The gap between the average family income and the cost of the average house grows wider every year. The average price of a house in Texas is $65,000; in order to buy it, you’ll probably have to put down 20 per cent of the total cost and have an average annual income of more than $40,000 just to qualify for the loan.

“ ‘The savings and loan tells me my buyer is not qualified to buy this house at eight per cent interest. So I ask if he is qualified to buy at thirteen per cent, and the answer is “You bet,” ’ says a Houston real estate agent.”

What is affordable to the first-time home buyer? “When people call me now to buy a fifty-thousand-dollar house, I don’t even pick up the phone,” says an Austin realtor. “They can’t buy a house if that’s all they can afford.” The median family income in Texas is $18,500, which means that many first-time Texas home buyers will have to settle for mobile homes. Although the construction of mobile homes (or “manufactured homes,” as dealers like to call them now) has improved considerably in the last five years, they are still the worst buy on the housing market, since they fail to hold their value. Next-worst are town houses and condominiums, many of which have been converted from older apartment buildings. Typically, they are easy to buy—if you’re buying from the developer—and nearly impossible to sell, unless the mortgage has been guaranteed by the U.S. government (VA and FHA loans are examples). Fewer than half of the state’s condo projects have federal backing, and potential sellers find that lenders won’t even take loan applications from prospective buyers. With a limited amount to lend, mortgage bankers prefer to place their money where the risk is minimal—in office buildings, for instance, or in expensive houses whose buyers already have large portions of equity to invest. Nobody is at a greater risk than the first-time home buyer, who gets less for his money than anyone in the market.

Anyone, that is, except the renter, who has barely begun to feel the effects of high interest rates and exploding property values. Apartment buildings have been the most attractive items on the market for high-rolling investors. Rental properties are usually resold every five to seven years, since after that point the tax advantages that landlords gain from deducting interest payments begin to diminish. That means that renters today are living in the economic climate of the mid-seventies, which is when the line on the graph of rising real estate values became almost vertical. If your landlord bought your apartment in 1976 at 8 per cent interest, what do you think will happen to your rent in 1981, when he sells it at three or four times his cost and the interest rate has nearly doubled? Texas renters in the eighties will be paying a penalty, not only for increased costs to the landlord but also for the shortage of apartments caused by the continuing migration to the Sunbelt, a hiatus in apartment construction, and the widespread conversion of existing apartments into condominiums.

If you are congratulating yourself on paying half as much in rent as your friend pays on a mortgage each month, consider what your situation will be five years from now. A fixed-rate thirty-year mortgage purchased this year will cost you no more per month in 1986, whereas the only possible brakes on soaring rents are a precipitous drop in interest rates and an oversupply of rental units (or rent control, which is politically unlikely in Texas). Even in the most optimistic circumstances, by 1986 you will be paying more in housing costs than your homeowning friend. A less sanguine forecast would show you paying a far higher percentage of your income in housing costs—a virtual rent slave, without equity and with little savings for a down payment on a home of your own. The best advice for renters is to buy now. Unfortunately, most renters will find that it’s already too late. They’ve been priced out of the market.

Watch it happen: a $60,000 fixed-rate mortgage at 8 per cent interest costs $440.26 per month; the same mortgage at 10 per cent costs $526.54—only a 2 per cent difference on paper, but actually a 19 per cent increase in the monthly payment. Over the life of the loan—thirty years—that 2 per cent difference will cost you more than $31,000. At the beginning of this year mortgage interest rates were over 14 per cent, meaning that the monthly payment on that same mortgage is $710.92. Interest rates may dip and swell throughout the year, but it’s unlikely they’ll fall below 12 per cent, and some economists expect them to rise again at the end of the year.

It’s easy to envision the consequences. People who would like to purchase homes will be trapped in apartments, where rising rents will crush low-income families and make it more difficult for people of moderate means to save the higher down payments required by lending institutions. And even if interest rates drop, prices of all homes will probably rise in response to the increased demand, which means that the cost of houses will continue to hover out of reach of most first-time buyers.

A World of Hurt at the Savings and Loan

Interest rates are high because the sources of mortgage money have dried up. Typically, home buyers get mortgages from a savings and loan institution (S&L), which in turn sells most of its mortgages to investors. In the past, that investor might have been an insurance company, a mutual fund, or a wealthy individual; these days it is likely to be one of the government mortgage companies. Investors stopped buying mortgages when other investments became more lucrative: Treasury bills, for instance, are more secure and have recently offered a higher rate of return; shorter-term loans to major corporations have been paying record rates of interest. The best investment, of course, has been real estate, and more and more investors would rather own than loan. The effect has been to drive up land prices because of the intense speculation and to drive up interest rates because of the flight of money from the mortgage market. In the past two years so many investors have turned away from mortgage buying that only the federal government and savings and loans are left—and the S&Ls already have one foot out the door.

“Of all the new mortgages, the one consumers should be most cautious of is SAM, the shared appreciation mortgage, under which you may be required to give, say, 30 per cent of the profit from the sale of your home to the institution that made the loan.”

“Savings and loans were created for one purpose: to raise local money to finance local building,” complains a spokesman for the Texas Association of Builders. “That was what gave financial strength to the homebuilding industry. However, S&Ls have gotten a bill through the last session of the Congress that makes banks out of them. Now they’ll loan on cars and jewelry and round-the-world tours. There will be less money available for home loans, and that will shoot prices up. It’s destroying the homebuilding industry.”

Realtors are complaining about the new attitude of S&Ls, which no longer want to make mortgages that aren’t competitive with other loans. “They charge exorbitant transfer fees, extra points, plus they go up to the maximum, maximum interest rate they can get,” says Barbara McCarver, past president of the Houston Real Estate Board. “In terms of their total conduct, they have gouged the public.”

More costly than the increased handling fees charged by S&Ls has been the enforcement of the due-on-sale clauses now found in most mortgages. In the past it was common for a buyer to put down the difference between the price of the home and the amount of the mortgage and merely assume the existing loan at the same interest rate. No longer. S&Ls don’t want to carry old loans at low rates, so they require completely new financing when the sale is made. Mortgages without due-on-sale clauses acquire extra value. And yet more than one realtor has experienced increased difficulty in qualifying buyers for cheap mortgages. “The S&L tells me my buyer is not qualified to buy this house at eight per cent interest,” says Houston realtor Emmett Kelly. “So I ask if he is qualified to buy at thirteen per cent, and the answer is ‘You bet.’ ”

Durwood Curlee, a lobbyist with the Texas Savings and Loan League, claims that “the mortgage loans we make will earn us from as little as one eighth of one per cent to a maximum of one or two per cent—and that’s in a great market. That same realtor who’s complaining about S&Ls is making six per cent of the purchase price right off the top, at no risk. If you want to say we’re gouging the public by lending at these rates, you’ve got to ask why we’re not making huge profits.”

It’s true that S&Ls are suffering. Last year was the worst in the history of the savings and loan industry, and according to Custis Hoge, a vice president of the investment firm Rauscher Pierce Refsnes, more than 50 per cent of the companies will show losses for the year. It is a situation that S&Ls partly brought upon themselves when they persuaded the government to let them issue money market certificates at competitive rates. “Say you are a depositor and you put your money into a six-month money market that matures this month,” explains Hoge. “The rate six months ago was eight and a half. If the S&L took your money and made a loan at ten or eleven per cent it did pretty well. Now, if you reinvest your money market certificate at the current rate of sixteen per cent, the S&L is stuck. There’s just no demand for money at that rate. S&Ls have been allowed to issue money market certificates since June 1978, and they’ve been struggling ever since. They wanted to prevent the drain of funds. What’s happened instead is that they’ve gone from having fifty to sixty per cent of their deposits in the form of passbook savings at low interest rates to twenty per cent in passbook savings with the rest in money markets and jumbo certificates of deposit. Now if you asked any of them to look back they’d say they wish they hadn’t done it.”

Money that we as depositors lend to an S&L can be lent back to us in the form of mortgages. For the past two years interest rates on various forms of savings have doubled and redoubled as a result of deregulation, but the percentage of disposable income that people actually save has remained the same—5.2 per cent, the lowest in the industrial world. One reason is that our disposable income has declined. We are poorer, in other words.

S&Ls have tried to recoup by offering a variety of new mortgage structures designed to make mortgage loans more attractive to investors. Previously a home buyer would put down 5 per cent of the cost of the house—or sometimes as much as 10 per cent—and receive from the S&L a fixed-rate thirty-year mortgage for the balance. The terms would not change over the life of the loan, so that the first monthly payment would be exactly the same amount as the last one thirty years later.

A home buyer shopping for a loan this year will be confronted with an array of bewildering acronyms for various mortgage plans—ARM, CAM, DIM, FLIP, GPM, PAM, PLAM, RAM, ROM, RRM, SAM, SNAP, VRM—everything but FLIM FLAM, which is what most of these offerings are. He is also likely to have to put quite a lot more money down—20 per cent is almost the norm—and the mortgage he is offered may be tied to the rate of inflation. The rollover mortgage (ROM), for instance, may be renegotiated (“rolled over”) every so often to make an adjustment in the interest rate. Although a lender can’t raise the interest rate indefinitely—right now the limit is 5 per cent for the life of the loan—rollovers are poor bets for consumers. They are designed to pass the risk from the investor to the borrower. Lenders defend these offerings by saying that interest rates may also go down, in which case the bank is the loser. Under Texas law, however, the holder of a mortgage at a rate over 10 per cent is entitled to renegotiate his loan without penalty if interest rates go down. That means fixed-rate mortgages are still the best deal for consumers, but they are disappearing from lending institutions all over the state.

“People who would like to purchase homes will be trapped in apartments, where rising rents will crush low-income families and make it more difficult for people of moderate means to save the higher down payments that will be required.”

The graduated payment mortgage (GPM) is one in which low monthly payments at the beginning of the loan are increased at intervals, so that buyers who may not be able to afford a fixed-rate mortgage will pay less now, more later. Some lenders pronounce GPM “gyp ’em.” Often the early payments on GPMs are not high enough to pay the interest, so that buyers, even after several years of payments, still owe not only the principle but also the accumulated unpaid interest.

Of all the new mortgages, the one that home buyers should be most cautious of is SAM, the shared appreciation mortgage, which has already made its debut in some states, although not yet in Texas. Under SAM, if mortgage rates are 14 per cent and the lender says you are not qualified to borrow the money you need at that rate, he may offer to give you a break on the interest in return for a portion of your profit—say, 30 per cent—when you sell your home. It’s a dismal prospect, but home buyers who’ve been priced out of the market by rising interest rates don’t have many alternatives.

“There’s less money in the real estate market for single-family homes because there’s no hedge against inflation for the lender,” says Glenn Justice, a mortgage banker in Dallas. “Lenders who are obligated for long-term mortgages have got to have more flexibility. If you give a thirty-year mortgage these days you’re hung with it. Of course, there are so many different types of mortgage instruments available right now, it really is cumbersome. It will probably settle down to some kind of rollover plan that is rewritten every three years. Buyers will have to put more money down. The other thing we’re going to see is shorter-term mortgages.”

Say good-bye to the fixed-rate mortgage and 95 per cent financing. Say hello to huge down payments and expensive new mortgages. Who can afford to buy property at that rate?

Plenty of Room at the Top

When the entrance of new home buyers into the market is blocked, there is bound to be a concentration of ownership at the top. Although most people have been shut out of the market because of high interest rates, that hasn’t stopped the acquisition of property. “In fact, we’ve had more investors buying property in the last year than ever before,” says Jim Wood, chief of the Mortgage Credit Branch of the Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) in San Antonio. Even in December 1980, with the prime rate at 21.5 per cent and mortgage rates above 14 per cent, banks in Austin reported an increase in loan volume of as much as 20 per cent over the same period the previous year. “Surprisingly, in this market, we’re looking at very substantial real estate transactions,” reports Bob Present, chairman of Capital National Bank. The kinds of loans Present is talking about are not single-family mortgages, though; they are big-money loans for apartment houses, vacant land, commercial buildings. Speculators are buying everything in sight, including the housing you may someday be living in.

What attracts investors to real estate are the tax breaks, such as mortgage interest and property tax deductions and depreciation of rental property. The interest and tax deductions are available to ordinary homeowners, but in diminished form, since the higher the bracket in which a person is taxed, the more attractive the tax breaks become. A person who earns $20,000 a year and pays $400 a month on a $40,000 mortgage could save $481 in taxes his first year of ownership; for the very same mortgage, the person who is fortunate enough to earn twice as much money will also save nearly twice as much in taxes—$895—because the income shielded would otherwise have fallen into a higher tax bracket. Obviously, the rising interest rates favor rich investors, since they can shelter a correspondingly greater portion of their incomes. “Once you catch on to the system,” says one investor, “you’ll never pay taxes again.”

Real estate is an especially attractive investment during a period of high inflation, when money races into tangibles. But unlike the soaring cost of precious metals or art or antique cars, which has only a marginal effect on the actual cost of living, the rising cost of real estate resonates all the way through the economy, like a troop of soldiers marching in cadence across a bridge. The bridge could have supported a dozen tanks, but it snaps in half because of the sympathetic vibration of marching feet.

“We’ve gotten to the point where people are buying houses as an investment, instead of as shelter,” Jim Boyle of the Consumer Federation of America says. “What we’ve done is to make real estate too attractive, with the result that new people are unable to buy in and investment capital that is badly needed elsewhere in the economy is all sunk into property. It has a very dysfunctional effect.” The dysfunction is not merely economic, it is profoundly personal—as you might guess by looking over your shoulder at California, where the median house price is over $100,000.

In the Temple-Killeen area, one of the fastest-growing sections of the country, an investor may acquire vacant agricultural land that he intends to hold for speculation. Although the investor is probably not a farmer or a rancher, he can qualify for an agricultural exemption that guarantees that he will pay a minimal amount of property tax. The Texas Legislature passed the exemption with the intention of preventing valuable agricultural land from turning into suburbs, but its effect has been to reduce the cost of holding such land, so that speculation is actually encouraged.

In three to five years land prices may have shot up to the point that the investor is ready to sell. He has already enjoyed tax write-offs that sheltered his other income. Let us say that he is taxed in the 50 per cent bracket and that he makes a $1 million profit from the sale of the land. If that $1 million had been income earned as salary, he would be liable for $500,000 in taxes. But since it is money made in an investment, it qualifies as a capital gain, which means that only 40 per cent of the total profit is taxable. For this investor, his tax bill on the $1 million profit is $200,000. In the usual scheme of things, he has sold to another investor, who sells to another investor, and so on, until the land is actually sold for development, divided into lots, and sold to home buyers—the ultimate investors. It is the homeowner who pays the tab for years of speculation that have run up the cost of the land—and he’s taxed for it, too.

And as more and more home buyers are priced out of the market, speculators buy the developed property, then rent out the house, condo, or town house at a rate that may be below the cost of the mortgage. The speculator (now the landlord) makes his profit in tax losses and on the appreciation of the property. Inflation can actually become a rent subsidy.

When you ask bankers and realtors who is buying property in Texas now, you hear first about Californians, and then about Canadians, Europeans, Latin Americans, and Arabs. It is the big-fish, little-fish syndrome: foreign money spills into California, jacking up prices and chasing California money into Houston; soon investors in Austin are complaining about rich kids from Houston who are laying off money in their old college town; next you hear the grumblings from Temple and Bastrop about Austin investors who’ve been priced out of their own market.

The biggest fish in the water are the insurance companies and pension funds. Fifteen years ago, before the inflation spiral began, insurance companies were a primary source of mortgage funds. But as interest rates went up, insurance companies began diverting some of their immense portfolios from mortgage lending to partial ownership of the properties—the commercial equivalent of the shared appreciation mortgage—and the giant pension funds, which were eager to diversify their investments, were right behind them.

“What the insurance companies did was to tell developers, ‘If you’re building a piece of commercial property, we want a percentage in the growth of income,’ ” says Glenn Justice. Over the years the portion of ownership retained by the insurance companies has grown to the point that they are now dispensing with the middlemen and becoming their own developers—in breathtaking fashion. Take a look at Las Colinas, which is being developed by the real estate arm of Southland Life: 12,000 acres near the DFW airport, in scope a virtual city of its own. “The problem we face now,” Justice says, “is the concentration of ownership of all properties by big insurance companies and pension funds. At some point some legislator is going to raise his hand and say the accumulation of wealth by these big insurance companies is dangerous.”

New legislation allows S&Ls to become land developers as well, and independent builders, such as Dub Dennis of Wichita Falls, are alarmed. “Now these institutions that used to lend us money can build and sell houses and apartment houses and own any kind of property that previously they could have acquired only through repossession,” Dennis says. “They’ve become a direct competitor and a very tough one. They develop lots on the same basis that I as a developer do, only they have the advantage of far larger amounts of capital. They acquire the land and then they set up their own group of builders and furnish them with the interim financing they need. There might be some points or extra charges to the builder along the way, but at the same time the S&Ls do lots of things that give their builders an advantage. They have money in that subdivision, so they make deals for their builders they won’t make for other builders or other home purchasers in the city.”

Naturally, S&Ls try to channel the mortgages they make into their own developments. Recently, the State of Texas issued some tax-free bonds to make low-cost mortgages available to home buyers. What happened in Wichita Falls, according to Dennis, is that the low-cost mortgages were reserved for the S&L subdivisions, at the expense of builders and buyers everywhere else. “There was an ad in the Wichita Falls paper that builders in their subdivision would build a house and furnish you with that money at the low interest rate. The money was supposed to be available on a first-come, first-served basis. When my buyers called, the people at the S&L said they were out of mortgage money, but they continued to make loans. What happened was that purchasers could get an 11.2 interest rate in the S&L’s subdivision, but they had to pay 14.5 per cent in mine.”

S&L spokesmen barely bother to defend themselves against the charge that they are reserving state bond money for their own developments. “Anything bad you want to say about that program,” says lobbyist Durwood Curlee, “I’ll agree with.”

Along with the increased profits S&Ls can realize as land developers come the increased risks traditionally associated with that profession. Not all S&Ls have proved to be the astute real estate tycoons they might have imagined themselves to be. North of Austin an S&L built a development on unstable land that later proved to be in a floodplain. A developer who makes mistakes has to take a loss; when the developer is an insurance company or an S&L, the loss is passed on to the shareholders, unless a catastrophe occurs, in which case the loss is shared by policyholders and depositors—that is, you and me.

The Future? What Future?

“The situation is very much like our agricultural system,” notes Pat Wooten, director of the Texas Real Estate Research Center (TRERC) in College Station. People ask, ‘What’s going to happen to the small farmer?’ Well, the stark truth of the matter is that he’s going out of business. The future homeowner is in the same position.”

Wooten agrees with his economists at TRERC that a model of the future economy of the U.S. may be found in the landlord-tenant system that prevails in Britain, where only 51 per cent of the population own their own homes (compared with 63 per cent in the U.S.), housing costs account for nearly half of a family’s disposable income, and the average age of a first-time home buyer is 44. As a matter of fact, housing costs in the U.S. are a bargain compared with those in the rest of the world. The average price of a house in Japan is $119,000—nearly twice that of an American home. In West Germany the cost is $226,000. One survey found that outside the communist countries, only Greece, the United Kingdom, and Australia reported lower average home prices than the U.S. That’s one reason foreign investors continue to pour money into American real estate, especially in California and Texas.

Economic mobility is a fundamental tenet of capitalism, but there is an ax falling between the social classes, and its name is equity. The haves and the have-nots of the future will increasingly be distinguished by the ownership of property. There has never been a more urgent time to provide alternate financing for first-time home buyers. A HUD panel has already warned of social upheaval in the face of rising rents and increased costs of home ownership. “Unless these problems are dealt with successfully, housing may become the Viet Nam of the eighties,” said one of the commission members. The panel proposed removing rent controls to encourage the building of apartments and dropping regulations against converting apartments into condominiums; modifying zoning and building codes to allow lower standards, smaller lots, and increased density; and reducing regulations against inexpensive mobile homes. If this sounds like carte blanche for unscrupulous developers, it is. But that is the future unless something is done to make financing more available to home buyers.

One obvious step is to stop taxing interest on savings accounts. Americans already have the lowest rate of savings of any industrial country. With the deregulation of interest rates, interest on savings income has risen substantially, but not enough to make it a good investment in today’s market. Making passbook savings the poor man’s tax shelter would provide more money for all kinds of loans. The principal objection comes from utilities and municipalities, which issue tax-free bonds to acquire money for directed growth. However, a marginally higher yield on such bonds would draw the big investors.

Jim Wood of HUD offers another approach, in which FHA and VA mortgages could have the same tax-exempt status as government bonds. “Say you’ve got a million dollars to invest, and you expect a fifteen per cent yield,” Wood says. “Your return is $150,000, but you are taxed at fifty-five per cent, so $82,500 of that goes to taxes. Why couldn’t that investment go instead to government-insured mortgages offered at ten or eleven per cent? The yield would only be $100,000, but it would be tax exempt.” This would extend some of the advantages of property ownership to the mortgage lenders, and it would make mortgage money available at below-market rates. Such mortgages should be limited to the people who need them the most: primarily first-time home buyers. The tax-free bonds issued by the State of Texas and individual county and municipal governments are offered only sporadically, and although they are supposed to be fairly distributed, they are obviously not. A more general program, such as the one Wood proposes, stands a chance of being more equitable.

DeWitt Hale, a lobbyist for the Texas Association of Builders, has suggested that state-controlled funds, such as the Permanent University Fund and the pension funds of state employees, be authorized to diversify their investments in order to lend money on “homeowner-occupied single-family dwellings.” Some retirement funds regularly purchase blocks of mortgages through the federal mortgage associations; Hale would like similar blocks to be assembled through state-chartered S&Ls. “There is not much risk because the investor would be holding the first lien on real property in the state of Texas. I can’t think of better security than that.”

The problem with these proposals is that they only extemporize with a problem that has so far resisted solution: inflation, which not only drives up the costs of goods and services but also draws money into nonproductive tangible investments, such as real estate. With the long-term demand for property and housing in Texas, costs will probably continue to exceed the grasp of ordinary consumers, so that the home of one’s own that is so conspicuously a part of the American dream will in the future be mainly a feature of the investor’s portfolio.

And then what? It’s a question that has been troubling Rick Floyd, one of the TRERC economists. “Thomas Jefferson believed that the fundamental basis of democracy is widespread ownership of property,” says Floyd. “What does it do to the local political situation when the ownership of property becomes increasingly concentrated in the hands of wealthy insurance companies and pension funds? We will see not just a tenant-landlord system but a system in which the property owner is an absentee landlord in the form of a very remote corporation. We all like to imagine that we have some say in the future of the communities where we live. But how does that decision-making process change when property passes out of the control of ordinary citizens?”

Where Will It All End?

The two crucial questions about housing answered at last.

Will things get better?

Not much. Mortgage interest rates should run several percentage points higher than the prime, a situation that is now reversed. And since mortgage rates usually stay ahead of the rate of inflation, they are likely to remain relatively high even during a stiff recession. But if the inflation rate would only stabilize, that would give lenders the confidence to make more money available. Even a moderate dip in the cost of borrowing money would have a dramatic effect on home buyers—and sellers, thousands of whom have been looking at For Sale signs in their front yards month after month. Any drop in the prevailing interest rates would also improve the profits of S&Ls, some of which may be going out of business if things don’t get better fast.

Will things get worse?

Although some forecasters talk about a cave-in of real estate values, it probably won’t happen unless we suffer a larger economic collapse. Even then, real estate may hold its value better than other investments. The truth is, things are already nearly as bad as they can be, with rising house costs multiplied by high interest rates. Look at the average house with a $60,000 mortgage, financed last year at 12 per cent interest. If the value of that house has risen at the rate of inflation—nearly 13 per cent—the new mortgage on that home would be $67,800. But with interest rates now at 14 per cent, the monthly payments have vaulted from $617.17 to $803.34—a 30 per cent increase in the actual cost of the home in one year’s time.

L.W.

Good Deal #1

Get out your tools.

Bankers call them “shells.” They are the dilapidated housing found in every city, the falling-down buildings in bad neighborhoods that seem to be marking time until their date with the wrecker’s ball. But sometimes these shells represent some of the finest architecture in the city, the kind of gracious homes that are unaffordable today. One of the most fortifying movements in the cities of this country has been the work of urban renovators who have restored such homes and the neighborhoods around them to the beauty they once enjoyed.

What made these houses good investments was the margin for error. They were so cheap that almost any improvement made a nice profit. That’s not true anymore. The price of close-in housing has shot up everywhere, and even the bargains may be a poor deal at today’s interest rates.

Four years ago you could have bought a shell in Dallas’s Munger Place for $18,000 to $22,000, and although it typically needed everything done to it—a new roof, new siding, major structural repair—homeowners who were willing to do much of the labor themselves could enjoy a virtual mansion for a small portion of the cost of a comparable new home. Now shells in Munger Place are selling for more than $50,000, and the most obvious candidates for repair have already been snatched up. People can’t afford to make mistakes at that price.

Ted and Sharon Patterson bought their home on Worth Street for $45,000 in April 1979. They didn’t know that the four-thousand-square-foot bile-colored behemoth had been dubbed “the green lizard” by neighbors. “The house was a repossession,” says Sharon. “We didn’t know any of its history. It had the square footage we were looking for and a minimum down payment. It turned out that we had bitten off a little more than we could chew.”

The Pattersons took out a $55,000 loan to buy the house. They hoped that the loan, added to $15,000 of their own money, would be enough to make the house livable. Then they would gradually put in another $25,000 worth of improvements. “I didn’t want to do any of the major work myself,” says Ted. “I tried to get a contractor to do it all.” The Pattersons soon found that the house needed more repairs than they had imagined, and workmen who got frustrated by the complications of fixing up old houses simply walked off the job. Soon Ted was back at the bank asking for another $35,000 loan. “It’s very painful making the payments right now,” he admits. “The house was never supposed to cost this much. How long it takes to finish is strictly a function of money. I’ll have to throw in the towel and learn how to be a carpenter myself.” Sharon has gone back to work to meet their increased expenses, and Ted sometimes finds himself in court because of disputes with his contractor. “This has been a hard-luck house for many people,” he says. “There were a lot of times—even this week—when I thought about giving it up.”

The Pattersons had hoped to have the house completed for $95,000. Now they estimate the final cost at $200,000. “What are our choices?” asks Sharon. “Everything we had saved for seventeen years is in this house. Are we supposed to walk away from it and go into an apartment, with no equity and two kids facing college? We really don’t have a choice. We’ll stay.”

L.W.

Good Deal #2

Get in on the ground floor.

Remember “no-frills” homes? Those were the ones with certain luxuries omitted, such as dishwashers, garbage disposals, and wall-to-wall carpeting. Now homebuilders have gone a step further, actually letting the buyer participate in the construction of his home. You decide how much of the home you can finish—from the interior wiring and Sheetrocking to the painting and wallpapering—and then find a builder who will include the cost of those materials in your loan. If you are handy and have more time than money, this is one sure way of getting more home for your dollar. However, if you can’t do the labor yourself, buying an unfinished house will probably wind up costing you more.

Modular, or prefabricated, units are another possibility, but they haven’t begun to make the impact in the residential market that was long ago predicted for them because they have usually been poorly designed. But stacked concrete cubes, such as the spectacular (and spectacularly expensive) Habitat in Montreal, which was designed by Moshe Safdie for Expo ’67, have become increasingly popular as dormitories and hotels (the Hilton Palacio del Rio hotel in San Antonio is one attractive example). Now builders are reexamining various forms of modular construction as one way of making housing more affordable.

Jimmie Muckleroy, an independent builder in Longview, has come up with a metal building that he calls a modified A-frame, which he can manufacture in his shop and erect on the buyer’s site within a week. He estimates that his A-frame costs about $4 less per square foot than a comparable wood-frame home, and it has the advantage of being virtually maintenance free. With eight inches of insulation in the walls and ceiling, it is also cheaper to heat and cool. Right now Muckleroy is building a three-thousand-square-foot four-family house for a customer who will finish the interior himself. The construction cost is $40,000. Muckleroy hopes to refine his modular units to allow the buyer to put up the entire building himself.

Another alternative for the handy is a house kit. The house kit industry began with log cabin vacation homes; now it is rapidly expanding into the single-family market. As with the modular unit, what you sacrifice in terms of personalized design, you make up for in economy. In the future, selecting a house may be little different from choosing a new car.

L.W.

Good Deal #3

Get moving.

The first principle in real estate is location: the better it is, the higher the price. Location is the first principle in house moving, too, only it works in the opposite direction: desirable houses are the cheapest ones, and they are the ones in the worst locations—in the path of a freeway, for instance. Every year thousands of nice old homes are razed to make room for shopping malls or filling stations. If you’re willing to put up with some headaches, you might find a bonanza.

Attorney Mahon Garry and his wife, writer Susan Ridgway, already owned the land, a plot near Taylor that has been in the Garry family since before the Texas Revolution. “Ever since I was a little boy I’ve wanted to put a house there,” Garry says. Garry and Ridgway wanted an old farmhouse, and they found one when a local farmer decided to build a new house next to his old one. “It’s twenty-five hundred square feet downstairs and a little less than that upstairs. It’s built on twelve-by-twelve beams. You just can’t buy a house like that these days.”

The farmer was glad to unload the house for $6000. Then Garry and Ridgway went to Earl Bradford, an Austin house mover. Because of the size of the house, Bradford had to cut it into two pieces and collapse the roof. “It looked like a giant had taken an ax and chopped it in half,” Garry remembers. The cost of pouring a foundation came to $2500, and Bradford’s bill for moving the house, setting it down, and rejoining it was $8000. “One of the major unexpected expenses was just getting the light and telephone lines out of the way. All along the route we had to have lines lifted or cut, and that cost us about a thousand dollars.”

The house still needed wiring, plumbing, a new roof, and new chimneys. “We could have moved in for less than forty thousand dollars, but we spent quite a lot more on some features, such as our cedar shingle roof,” Garry says. “You’ve got to be crazy to move a house, but once it was done, we were real happy we had been crazy.”

L.W.

Good Deal #4

Get back to the land.

The elemental building block of the primitive world may be making a comeback. A physicist named Sam Lyles, formerly associated with Texas A&M, has been experimenting with making adobe, one of the first building materials in Texas, more durable and water resistant by mixing it with asphalt and other impermeable substances. He calls the result “asfadobe.” “You can soak my bricks for two weeks and they’ll pick up less than one per cent moisture,” Lyles says. “That’s a lot better than what the building codes require.”

As a consultant, Lyles has helped to build mud houses in nearly a dozen underdeveloped countries, and he thinks the time has come—or come again—for mud homes in the U.S. “Looking at all the housing problems in this country, I see all the signs that I’ve seen in developing nations. The problems are quite severe and they’re going to get much worse.”

Lyles isn’t the only convert to adobe. An El Paso architect named Mack Caldwell has already built several adobe structures, including four private homes and a seven-unit apartment building. They are not cheap. The single-family houses range from 2500 to 3500 square feet and cost between $135,000 and $160,000. They have twenty-inch-thick walls and passive solar features like south-facing windows and elaborate weatherproofing. Although they do require some supplementary heating systems, Caldwell says solar power provides 50 to 80 per cent of their heat.

Caldwell is trying to make adobe construction more affordable. Right now he is building a prototype adobe home with a grant from the Department of Energy. It is a small (nine hundred square feet) two-bedroom home with passive solar features and walls sixteen inches thick. Caldwell hopes to complete it for only $21,550—a mere $24 per square foot. “This house is designed for low-income families,” he says. “We’re trying to get the price down to the bare minimum.”

There’s something grimly appropriate about a return to mud houses. What’s next? Caves, no doubt.

L.W.

- More About:

- TM Classics

- Longreads