ON A SUNNY NOVEMBER AFTERNOON AT A SMALL LAKE IN Southern California, three supermodels were sitting on a boat dock eating potato chips. “All right, guys, crunch a little louder,” shouted a man holding a clipboard, and the gloriously shaped Vendela, Kathy Ireland, and Naomi Campbell, trying to appear as dignified as possible, stuffed more chips into their mouths. A film crew, a dozen production assistants, makeup artists, hairstylists, and some advertising and marketing executives from Frito-Lay, the biggest snack food company in America, looked on anxiously. “Come on, more passion!” the director urged as he peered into the camera. The supermodels crunched again.

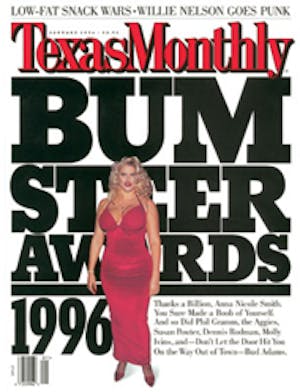

It was the first day of filming for one of the most important television commercials in Frito-Lay’s history—a thirty-second spot introducing Baked Lay’s, which the company says are the world’s first low-fat potato chips that taste like regular potato chips. For the past decade every major American food company has been working feverishly to create a truly great-tasting, low-fat snack that will capture the stomachs of American consumers, whose top concern is now fat intake.

With Nabisco introducing a wildly popular line of low-fat SnackWell’s cookies and crackers and Procter and Gamble pushing to win federal approval of olestra, its breakthrough fat substitute, Frito-Lay is pinning its hopes on Baked Lay’s—the result of a secret three-year research project conducted by scientists at the company’s headquarters north of Dallas. While there are plenty of low-fat corn chips, pretzels, and other snacks, there is no popular low-fat version of the potato chip, which remains America’s favorite snack food. Beginning New Year’s Day, the company will spend $50 million in national advertisements and grocery store promotions exalting Baked Lay’s, which have only 1.5 grams of fat per serving, compared with 10 grams for a serving of regular Lay’s Potato Chips. The company’s marketing team has come up with such offbeat stunts as a potato-laden Rose Bowl float, which will include Vendela, Naomi, and Kathy eating Baked Lay’s and waving at the crowd. The commercials will show the supermodels slipping away to a fishing lake so they can talk about football and home repair and eat as many Baked Lay’s as they want. In another commercial they play poker, smoke ci-gars, and eat Baked Lay’s. At the end of the commercials, the voice-over says, “Now you can eat like one of the boys, but still look like one of the girls.”

Because of test marketing in, of all places, Midland, Texas, and Cedar Rapids, Iowa, Frito-Lay executives have such confidence in Baked Lay’s that they expect national sales to top $200 million by the end of 1996—an unprecedented success for a first-year product in the snack food business. “Never in our history have we done a national rollout of a new product like this one,” says Tod MacKenzie, the company’s vice president of advertising and public affairs. With $5 billion in sales a year, Frito-Lay seems to have an ingenious ability to figure out what Americans crave. It already controls almost 50 percent of the U.S. snack food market. Nearly eight billion bags of Frito-Lay snacks were purchased in 1994: Thirty-two for every person in the United States. According to a survey of the nation’s supermarkets, the seven top-selling brands of snack food are all Frito-Lay products: At the top is Lay’s Potato Chips, followed by Doritos, Tostitos, Ruffles, Fritos, Rold Gold pretzels, and finally Cheetos. Can Baked Lay’s join the list? “Despite all the predictions we’ve made, this is still an enormous gamble for us,” says one company insider. “If this fails, we’ll look as bad as Coca-Cola did when it introduced New Coke. Of course, if this succeeds, then we are on our way to taking over the whole market.”

FRITO-LAY IS HEADQUARTERED IN A LOW-SLUNG COMPLEX IN A remote area of Plano, hidden from the nearby roads and highways. Part of the headquarters is built over a creek that feeds into an elongated man-made lake, and on the grounds are tennis courts and groomed jogging paths. A large fitness center is near the lobby. The complex is the magic kingdom of snacking. There are no union strikes here, no hostile takeovers, not even bad corporate art on the walls. For the aesthetic benefit of employees who spend their days pondering the fate of Chili Cheese Fritos, the company has amassed a startling contemporary art collection, including works by David Hockney, Frank Stella, Jasper Johns, and Julian Schnabel. In the research and development department, preoccupied scientists walk past the famous Richard Avedon photograph of a young man holding a baby upside down.

What strikes a visitor about Frito-Lay is that almost all the vice presidents and senior managers are in their thirties and early forties. They act perky and dress casually. The executives keep bags of chips near their desks, and they snack throughout the day. “If I’m stressing, I eat Fritos or Cheetos,” says spokeswoman Lynn Markley, who is 35. “If I’m having a good day, it’s Tostitos with salsa.”

Some people might be a bit embarrassed about devoting their lives to getting other people to graze on potato chips the way cows eat grass. But this generation of Frito-Lay executives grew up on snacks and consider themselves experts in one of mankind’s oldest pursuits: oral gratification. They spend hours discussing “PCs” (Frito-Lay’s shorthand for “potato chips”) and “TCs” (“tortilla chips”). They talk about a chip’s “mouth feel,” “crunchy versus crispy sensations,” and “tooth pack” (the little soggy pieces of chip that are left in the mouth after the main part of the chip has been swallowed). In company parlance, “market share” is replaced by “stomach share.” The way Frito-Lay executives see it, an average American’s life can be charted by the Frito-Lay products he or she eats. Children adore the polystyrenelike Cheetos because they can lick all that orange stuff off their fingers. Adolescents turn to Doritos because the taste is bolder and the crunch louder, and because the infamous Nacho Cheese breath fits a teen’s budding irreverence. Young adults, who start going to more parties, begin to feel a need to dip their chips into something, which leads them to Ruffles and Tostitos. Older adults worry about their waistlines, so they turn to low-fat products like Baked Tostitos and Rold Gold pretzels. The company also markets particular chips to different populations. While the standard Lay’s potato chip is still promoted as the ultimate family snack, Fritos, most popular in the Southwest and Midwest, have become what senior vice president of marketing Brock Leach calls “the snack for down-home Americans who like pickup trucks and country music.” (The company uses Reba McEntire to promote Fritos.) On the other hand, Salt and Vinegar Lay’s are sold almost exclusively to residents in the Northeast, who, apparently, prefer a life filled with sour tastes.

Frito-Lay researchers make a point of knowing more about potato chip eaters than most adoption agencies know about the lives of prospective parents. Each year, they conduct hundreds of thousands of consumer interviews. “We ask questions like, ‘If you were going to open a bag of Doritos, what kind of music would come out of the bag?’” Karen Snepp says without a hint of irony. Snepp has perhaps the most fascinating job title in corporate America: vice president of customer and consumer insights. “It’s important for us to know what kinds of emotions are generated by our chips.”

While some skeptics might doubt that Crunch Tators or Funyuns can offer emotional insight, no one can deny that Frito-Lay has created some distinctly American taste sensations that cannot be compared to anything else. What else tastes like Nacho Cheese Doritos, a cataclysmic combination of dried cheese, onion, garlic, and tortilla chips? Where can anyone find anything close to Ruffles, which are almost all salt and crunch? Indeed, there is no other Texas business that has such an enormous impact on the country’s eating habits.

And the company is never satisfied. In the closely guarded research wing of the building known as the Potato Chip Pentagon—a visitor must be identified and checked by a security guard to get through the locked doors—a group of brilliant men and women with doctorates in synthetic organic chemistry and nutritional science toils into the night hoping to come up with the next best-selling chip. At a research facility in Wisconsin, the company has built several large greenhouses where scientists are constantly tinkering with potatoes, cross-pollinating them, cloning them, genetically engineering them, trying to create the perfect low-sugar potato (it’s the sugar, not decay, that creates the ugly brown spots on a chip).

The company’s theory is that while consumers know what they like, they don’t know what they might like. Besides Baked Lay’s, this year Frito-Lay will introduce a type of Cheetos that are in the shape of rectangular grids. There are plans for a product called Fritos Texas Grill (a corn chip that is less oily than the regular Frito and has grill marks), a new snack called Doritos 3Ds (a hollow triangle of puffed corn that comes in nacho cheese and ranch flavors), and chocolate-covered Rold Gold pretzels.

How did the world of salty snacks get so complicated? It was only in 1853, when railroad magnate Commodore Cornelius Vanderbilt, visiting a resort in Saratoga Springs, New York, complained that his fried potatoes were too thick. Irritated by Vanderbilt’s fussiness, the cook, a Native American named George Crum, sliced up a set of potatoes as thinly as he could, tossed them into boiling oil, fried them to a crisp, salted them, and gave them to Vanderbilt. His prank backfired. Soon “Saratoga Chips” were the rage of East Coast society, and eventually they made their way across the country. Dozens of small regional companies sprang up, mainly because potato chip manufacturing was such an easy business to start. All a person needed to do was hand-cook his potato chips on a kitchen stove, bag or can them, and then sell them around town.

In the thirties someone thought the country could use a different type of chip. Elmer Doolin, the owner of a struggling ice cream company, walked into a San Antonio restaurant and spent 5 cents on a small plain package of corn chips. Inspired, he hunted down the manufacturer, who happened to be a homesick Mexican who wanted to return to his native country. Doolin paid him $100 for the recipe, his handful of retail accounts, and his production equipment. Months later, Doolin began selling corn chips that he called Fritos out of the back of his Model T.

At the same time, a young entrepreneur named Herman Lay began selling his brand of potato chips out of his car in Nashville. Both businessmen were masters at buying smaller companies and adding products—Doolin tried selling a Frito peanut butter sandwich, and Lay sold fried popcorn called Lay’s Tennessee Valley Popcorn. The merger of the two companies on September 25, 1961, not only created a $135 million Dallas-based corporation that immediately dwarfed its competitors but also set up the first national distribution system for the company’s best-selling brands of chips—Lay’s, Fritos, Ruffles, and Cheetos—coast to coast. During the sixties, when the baggy-eyed actor Bert Lahr said “Betcha can’t eat just one” in television commercials for Lay’s potato chips, the public was captivated and Lay’s became a staple of American life.

In 1965 Frito-Lay and Pepsi Cola merged to form PepsiCo. But even as part of a corporate colossus, Frito-Lay employees were able to spot new snacks. In 1964 a Frito-Lay marketing vice president named Arch West noticed that people in Southern California were buying greasy bags of toasted tortillas. West thought Frito-Lay should have a similar product—a tortilla chip that could fit between the light Lay’s potato chip and the heavier Frito. He chose the name Doritos (“dorito” means “little gold” in Spanish). The company’s first television commercial for Doritos showed teenagers playing guitars as the announcer said, “What’s the biggest news since the Big Beat? Doritos are a swinging, Latin sort of snack.” For reasons no one can explain, kids loved the commercial. According to one history of the snack food business, when Doritos came out nationally in 1966, it almost overnight became America’s second most popular snack item (behind Lay’s).

Even when the phrase “junk food” became popular in the early seventies to describe salty snacks—Ralph Nader hosted a “Junk Food Hall of Shame” exhibit, and President Nixon’s adviser on food and nutrition publicly questioned the value of potato chips—Frito-Lay’s sales continued to explode. In the eighties, hungry for more market share, the company began introducing one product after another. First came Tostitos tortilla chips, another derivative of the corn chip; in 1981, after just one year on the shelves, Tostitos accumulated sales of $150 million. But there were just as many failures—O’Grady’s (a homestyle kettle-cooked chip), McCracken’s (a chip made from apple slices), Toppels (bite-size cracker-type snacks in four cheese flavors), Rumbles (bite-size granola snack bars), and Kincaid’s (a thicker and crunchier potato chip). According to one competitor, Frito-Lay was “just throwing everything at the wall to see what would stick.”

By the late eighties, “We were falling in our own doo-doo,” as a company official put it. The company was still profitable, but sales were falling in most areas, and competitors were catching up. To just about everyone’s shock, focus groups and taste tests showed that consumers liked Eagle Potato Chips better than Lay’s. Snacking is a fickle business. If a product doesn’t taste right, consumers quickly switch brands. After the company’s operating profits dropped 16 percent in 1991, more than 1,800 Frito-Lay employees were laid off nationwide. In a further slap at Frito-Lay, Eagle Snacks announced it would move its headquarters from St. Louis to Dallas.

Anxious directors on the PepsiCo board asked Roger Enrico, the Pepsi executive who had gained national fame leading Pepsi against Coca-Cola in the cola wars of the eighties, to come to Dallas to turn Frito-Lay around. As part of what he called the “PC Revolution,” Enrico cut out the coat-and-tie mentality, brought in a younger group of staffers, and demanded that all the products be updated. For the first time in 58 years, the Fritos bag was redesigned with brighter colors. The 27-year-old “Ruffles have ridges” advertising line was changed to “Get your own bag” (the ads for Ruffles featured characters making up wild excuses for why they couldn’t share their chips). And just as he had hired Michael Jackson and Madonna to promote Pepsi, Enrico went after celebrities for Lay’s and Doritos. As part of a $50 million campaign to introduce an improved Doritos, which were called “Nacho Cheesier,” George Foreman and his sons were hired to appear in a television commercial. And in the first new television commercial for Lay’s in more than a decade, Kareem Abdul-Jabbar made a bet with Larry Bird that he couldn’t eat just one Lay’s.

Combining the ad campaign with aggressive price-cutting tactics, Frito-Lay had regained its stranglehold on the snack market by 1992. With the introduction of a multigrain snack called Sunchips and a newly shaped Lay’s chip called Wavy Lay’s, along with low-fat Rold Gold pretzels and Baked Tostitos, the company’s sales were higher than ever. There was just one more thing to do—re-invent the potato chip.

AT THE START OF THE NINETIES, WHILE regional companies such as the Austin-based Guiltless Gourmet were having limited success selling their low-fat chips to health-conscious consumers, Frito-Lay’s research was showing that mainstream consumers disliked the products because potato chips without fat tasted like cardboard. “Yet even as our focus groups told us they hated low-fat chips,” said consumer insights vice president Snepp, “they also kept saying that they would do anything for a low-fat potato chip that had a decent taste. We realized that the one great place still left for us to grow was in potato chips.”

Every competitor knew it too, which was why they were desperately working on their own low-fat potato chips. The problem was science. While it was easier to get fat out of corn chips or pretzels, a potato chip needed to be fried in oil to have any taste at all. In one experiment, Frito-Lay’s technology department tried using vegetable oils that were lower in saturated fat, but those oils broke down when heated. Researchers then came up with a way to cook chips in a fryer and blow hot air over them to remove some of the fat. Frito-Lay was able to reduce the fat by 40 percent, but still it couldn’t develop a large enough following for the chips. Frito-Lay seemed stuck with its basic Lay’s potato chips—a one-ounce bag contained a vicious 150 calories and ten grams of fat. With the rise of tortilla chips, the potato chip market was suffering. In 1980 Lay’s represented 64 percent of Frito-Lay’s sales. In the nineties it was only 47 percent.

Then, in early 1993, Louise’s, a small company in Kentucky, came out with a product that was essentially microwaved potato chips with no fat. The taste wasn’t like a Lay’s potato chip, of course, but it wasn’t bad. Frito-Lay studies showed that consumers were interested. Suddenly, a sense of urgency was sweeping through the company.

The top-secret research endeavor was referred to only as Project Liberty—a reference to Frito-Lay’s goal of liberating the fat from a potato chip. Project Liberty was led by the company’s senior vice president of technology, Dennis Heard, a gregarious Scotsman who had received his doctorate in chemistry from the University of Edinburgh. Heard is the type who likes to wax about the potato chip the way Wordsworth once wrote about rural England. “The creation of a new potato chip,” he says, “requires a level of intellectual understanding and a degree of engineering discipline that is just as complex as building an automobile. Our goal was to find a unique structure, with a crunch so texturally satisfying and a taste that created a glorious chemical reaction between the surface sugars and starch of a potato.”

Frito-Lay’s scientists had made many breakthroughs in the past—one wall of the research department is filled with framed Frito-Lay patents, including one for a new strain of potato perfectly suited for potato chips—but the idea seemed preposterous that they could create a drastically low-fat chip that tasted like a Lay’s. In essence, they were being asked to invent an oven that worked as a fryer.

Initially, Heard had two young potato-obsessed researchers named Eve Lawson and Nancy Moriarity send sample chips through a variety of devices, from heated dryers to a specially rigged microwave to gigantic toasters. Early on, it was decided that straight slices of potatoes, which required more heat to be cooked, would not work. They needed potato flakes, a sort of flattened mashed potato, with much of the water already removed.

A small prototype oven was finally created (for proprietary reasons, Frito-Lay will not allow outsiders to see the oven), and every couple of weeks, the research team sent a “white bag” (a sample of their low-fat chips) to management for review. Even though no one could honestly say the chips were very good, Frito-Lay president Steve Reinemund, a 47-year-old ex—Marine officer who replaced Enrico after Enrico moved to a higher position with Pepsico, announced that he wanted a low-fat potato chip in a test market by 1994. The product, he said, was going to be called Baked Lay’s. Soon rumors were flying around the Potato Chip Pentagon. The new chip was going to carry the famous Lay’s name, so it had better taste good.

Heard added nearly thirty researchers to Project Liberty. A team of “flavor specialists” proposed adding a light garlic-and-onion seasoning to enhance the taste of the chip. That didn’t work. Then another team suggested using one of Frito-Lay’s specially grown potatoes with a higher sugar content. That didn’t work either.

But the scientists did make some improvements—they made the chips thinner, for example—and in August 1994 Wayne Calloway, the sometimes-hard-to-please chairman of the board of PepsiCo, flew to Dallas for a personal taste test. A white bag arrived in the Frito-Lay boardroom and Calloway opened it. As Heard remembers the moment, “Mr. Calloway took one bite and this look crossed his face. Finally he said to us, perhaps a bit sarcastically, ‘Do you really think this product deserves the Lay’s name?’”

Everyone in the room traded glances. The company was already committed to sending Baked Lay’s to the test markets that October, and here was Calloway telling them they had failed. Heard quickly gathered his team. They had to come up with a better product by Thanksgiving 1994, Heard said, “or we’re looking at a major embarrassment. My friends, the screw has been tightened.”

In charge of improving the recipe for Baked Lay’s was Frito-Lay principal scientist Tony Bello, a 37-year-old Nigerian who had received a doctorate in cereal chemistry at Texas A&M. In the processing lab, a room the size of a high school gymnasium where the scientists and engineers created their experimental ovens, Bello tried out twenty different samples (none of which he will describe because the information is considered a trade secret). He added sugar; he tried various amounts of fat; he ran a “surface response design,” in which the potato flakes were applied to the cooking sheets at various pressures.

On October 8, 1994, a particular sample came out of the oven, and a desperate Bello sunk his teeth into it. He yelped. “For me, as a food scientist, it was a eureka moment,” Bello says. “I knew we had found the right taste.”

Wayne Calloway returned in December. Another white bag was brought in. He bit into the chip, paused, and said, “Now this is a Lay’s.”

According to federal food regulations, the product is not a “chip” because it does not come from a slice of potato. Nevertheless, the new Baked Lay’s Potato Crisps were sent to the test markets in Cedar Rapids and Midland, two cities that Frito-Lay researchers say are the best reflection of mainstream America because of their incomes, ethnic mix, and average number of kids per family. The test market results were astonishing. Baked Lay’s flew off the shelves. What’s more, people weren’t sacrificing their purchases of other Frito-Lay items to buy Baked Lay’s. In total, Frito-Lay’s sales in the two cities were up by 15 to 20 percent.

In early 1995 an ecstatic Reinemund announced that he wanted to unveil Baked Lay’s nationally in time for the Super Bowl in January 1996. Frito-Lay had received massive media attention for its Super Bowl ads the last couple of years, and he thought the same sort of attention should surround Baked Lay’s. (Frito-Lay even paid to sponsor the coveted Super Bowl pre-game show.) At meetings, the marketing executives called Baked Lay’s “the snack of the century.” An advertising team from BBDO in New York began working on commercials that they prayed would out-do the hype that surrounded the Doritos commercial from the 1995 Super Bowl starring Mario Cuomo and Ann Richards. Meanwhile, Heard’s engineers worked around the clock to build four new ovens, each the size of seven eighteen-wheeler trucks, to handle Bello’s recipe.

BACK ON THE LAKE IN SORTHERN CALIFORNIA, the supermodels’ acting skills were on full display. Kathy Ireland was cracking down on her Baked Lay’s like a snapping turtle, while Naomi Campbell was learning to speak her lines with her mouth clogged with chips. Vendela showed her dexterity by bending over—in a pair of breathtakingly tiny denim shorts—and grabbing a bag of chips lying on the dock.

“Veeeeeery nice!” the director exclaimed.

In a food industry that introduces thousands of new products a year—including more than 1,300 low- and non-fat products alone in 1995—no one can say for sure whether Baked Lay’s will become America’s next great snack. With less salt than a regular Lay’s, it doesn’t have that same zing with each crunch. Some people will probably describe Baked Lay’s as less-tasty Pringles, the flat potato crisp made by Procter and Gamble that comes in a tennis ball can.

But Frito-Lay is betting that Baked Lay’s will create a revolution among consumers. In fact, believing that low-fat snacks will make up a third of its business by 1998 (as opposed to 10 or 15 percent today), the company is investing $225 million in its reduced-fat products, building new factories in three states and adding fifteen manufacturing lines to existing plants. Frito-Lay’s competitors seem helpless against such an onslaught. In late October Anheuser-Busch, the parent company of Eagle Snacks, the country’s second largest snack food company, announced that Eagle Snacks was up for sale because of poor earnings.

As long as Americans snack—and in the nineties snacking has become a fourth meal, the source of 25 percent of our calories—Frito-Lay will keep churning out the chips. Each day, the executives will arrive in their casual clothes at their elegant headquarters in Plano with more plans for capturing more share of stomach. And if Baked Lay’s never catches on? “Do not worry,” Dennis Heard says. “We are working on more than thirty new snacks. You will never escape us.”