This story is from Texas Monthly’s archives. We have left the text as it was originally published to maintain a clear historical record. Read more here about our archive digitization project.

It would be different,” Charlie Coyle told me, “if these girls only did what they said they’d do.” Charlie, a large, lumpy man with thin black hair and a sagging but not sad face, was sitting in a wooden chair in the small security office of the old Adolphus Hotel in Dallas. Across from him behind a desk sat Charlie’s boss, Lou Speer. Charlie was working the three-to-eleven shift, taking over from Lou, who relieves the late-night house detective at seven in the morning. In the small ritual changing of the guard, the man going off duty reports to the new man anything he’s noticed that could develop into trouble and recounts the outcome of any incidents. Last night there had been a minor fracas.

“She cut him down the side of his face with one of her shoes,” Lou told Charlie. “She had one of those spike heels. God. He bled everywhere.” The girl got away after that but the man went into a rage and pulled down the shower curtain and threw anything he could find against the wall. The commotion caused guests in nearby rooms to call the desk clerk, who sent the night officer to investigate. He calmed the man down. By that time he was more worried about stopping the bleeding than anything else. The night man left a report for Lou, who visited the room that morning. “Boy, he was meek as a kitten,” Lou went on. “There really wasn’t much damage—busted shower curtain rod was about all. But there was blood all over the bathroom floor. He said she didn’t steal nothing from him. He’s paid for the rod and everything, so I guess that’s that.”

The two men both shrugged. “He must’ve tried to hold out on her or something to make her so mad,” Charlie said. “But it doesn’t take much,” he went on, turning to me. “These girls aren’t there just to have sex and get paid. It would be different if they were. Not so much trouble for us. They’re there to steal.”

This straightforward statement represents a radical change in the attitude of hotel detectives from the days when the house officer, as part of his routine, might challenge guests with the line, “Is there a woman in your room?” In the past, house officers, while they shared today’s concerns with theft, fire, loud disturbances, and the general safety of guests, also felt obliged to uphold the moral reputation of the hotel. In the classic work from this period, I Was a House Detective by Dev Collans, published in 1954 and now long out of print, Collans made much of his diligence in discovering females in the rooms of male guests and his skill at spotting couples who might register together but were either not married at all or not married to each other. He had bellboys report couples who wouldn’t open their suitcases while the bellboy was still in the room; married couples didn’t hesitate to. A man in sleek clothes with a woman whose shoes were run down at the heels was another giveaway. Collans suspected couples who rang for drinks in their room immediately upon registering instead of going out for drinks; he also suspected couples who tended to sleep very late in the morning. And he reserved for his final chapter the long, slightly dull story of the only time he “knowingly allowed unlawful cohabitation to take place.”

Modern hotel detectives knowingly allow cohabitation, unlawful and otherwise, to take place every day of their lives. Not only have attitudes changed—no hotel is likely to lose its reputation because it allows an unmarried couple to register—but present legal opinion is that, all other things being equal, hotel guests may invite anyone they please to their rooms for a visit. The security staff in most hotels tries to prevent known prostitutes from soliciting in the hotel’s bars and restaurants, but a guest may escort a woman to his room who has been evicted from a bar earlier in the evening. Still, every hotel detective I talked with, from those in the plainest hotels to those in the fanciest, said prostitution was still their main problem. A clever working girl can get the money she’s been promised, then clean out her client’s wallet and possibly his luggage, and escape from his room with her virtue, at least the sexual part of it, intact.

“No, they don’t usually carry guns or nothing,” Lou Speer said. “They don’t really have to. A lot of times they’ll get out of the rooms just by saying they’re going down the hall for some ice to put in their drinks. Hell, I’ll bet you that somewhere in this city some old boy’s in his room right now waiting for a girl to come back with the ice. Usually what they do is make sure the mark takes off his clothes first. That’s not too hard. Hell, he’s got his own ideas about what she’s there for, so all she has to do is just heat him up a little bit, and he’s not going to think twice about stripping down. Then, with him naked as a jaybird she can grab his wallet and run out the door and there’s no way he’s going to come running after her.”

Speer, a veteran of twelve years with the Dallas police and eight in hotel security, has more on his mind at the moment than streetwalkers. This morning, in addition to looking over the damaged curtain rod and bloody room, he has tried to recover a missing briefcase that was either stolen from a guest’s room or lost by him somewhere outside the hotel. And he has had to question a number of employees because one of them had stolen a jar containing small contributions toward an employee Christmas party. Then there was the matter of the baseboards that someone had pried loose in the hallway on the thirteenth floor during the night.

Still, guests and their complaints come and go, a thief among the employees must be ferreted out and fired, the next act of vandalism will have a different target and most likely be by a different vandal. But the prostitutes are a constant, the same girls and the same patterns of theft repeated over and over. The women depend on getting into the hotel for their livelihood; the detectives depend on keeping them out for theirs. And if other hotel detectives, while naming prostitution as a major problem, are not quite so absorbed with it as Lou Speer’s men, it is because the Adolphus finds itself today in a situation it has helped cause without being really at fault.

Built in 1912 by Adolphus Busch with money from his St. Louis brewery, the Adolphus was once the premier hotel in the Southwest. It is still a nice hotel with an attractive brick exterior, a large and stately wood-paneled lobby, and comfortable if no longer luxurious rooms. All in all the management is doing the best it can to maintain the Adolphus in the tradition of grand old downtown hotels. This is a difficult task because, located at the intersection of Commerce and Akard, the Adolphus is directly across the street from a parking lot one block square and catercorner from the rival Baker Hotel, an establishment of somewhat later vintage and lesser class than the Adolphus. Three blocks east stands the Hilton, a newer and generally more bustling hotel than either the Adolphus or the Baker, but closer to them in price, clientele, and general ambience than the two grander downtown hotels, the Fairmont and the new Hyatt.

Although no one intended this to happen, the presence of the Adolphus, Baker, and Hilton has helped transform Commerce street at night into a kind of promenade for streetwalkers, police, pimps, taxi drivers, loners, hotel guests, ambulatory crazies, and the metabolically restless—although, in keeping with the general deadness of the rest of downtown Dallas after dark, all these types add up to something considerably less than a throng. I know of no city where the downtown streets become deserted so quickly after dark as in Dallas. You can look down Elm or Main and not see anything more than a car or two waiting at a stoplight or a garbage truck making its rounds. As soon as business closes for the day, Dallas begins to assume that empty, eerie silence characteristic of most cities only long after midnight. Along Commerce, by day a busy commercial street, only one business other than the three hotels remains open at night. The Copper Cow, halfway between the Adolphus and the Hilton, is a 24-hour restaurant with Formica booths and fluorescent lights, whose adjoining bar, a place of special fascination we will visit later, is named El Rancho Grande. This restaurant and bar is a retreat for those of that thin promenade who remain downtown after dark, including the women whose business takes them along Commerce from one hotel to another during an evening.

That business gives the work of the hotel detectives at the Adolphus a special focus and a special tone. In most ways they are like the other men in their field, affable ex-cops, for the most part, who have either retired or resigned from the force and are now applying their security training to their jobs at the hotel. In general, besides trying to prevent prostitution and theft, the house officer usually screens hotel employees, makes regular patrols of the hotel watching for open doors, suspicious persons, fires, or anything else that seems unusual, and does anything else that seems necessary to maintain a safe and orderly inn. In part this is simply good business, but it is also a hedge against lawsuits, since recent court decisions have held hotels liable for assaults and thefts that guests have suffered when, in the opinion of the courts, the hotel’s security was not adequate.

In the newest and grandest hotels, security is given much more consideration than it ever was in the past, and if the usual modern hotel detective is no longer cut from the old, cliched pattern—a pudgy, thick-witted gumshoe who sits in the lobby peeking through a hole in his newspaper—neither does he run a thoroughly modern operation like security officers at Houston’s Galleria Plaza, who, in addition to maintaining a staff of eleven, employ $30,000 worth of closed-circuit television, walkie-talkies, and other electronic wonders.

At the Adolphus, there are no closed-circuit televisions, but there is something else. Lou Speer picked up a thick stack of notepaper held together by a metal clamp. “These here are hooker reports,” he said. “If my night man sees a girl come in with a guest, he writes down when they come in and what room they go to. Like this one here—‘12:11 a.m., hooker to room 1017.’ Then I keep these reports and if a guest comes down in the morning and says his wallet was stolen out of his room, the first thing I do is look up in my hooker reports to see if he had a girl up there. The guest is trying to say the hotel was responsible for the loss. You ought to see the expression on some of their faces when I say, ‘But what about that girl you took up to your room at twelve-eleven last night?’ ”

It was now getting on past three and Lou Speer completed the changing of the guard by handing Charlie Coyle a large ring of keys, which Charlie accepted and stuck in his pocket. Leaving Lou in his office to interview another employee in the missing-Christmas-fund probe, Charlie and I walked together into the somber, cavernous lobby of the hotel. The Adolphus was less than half full and the lobby, except for an ancient bellboy and the room clerks behind the desk, was empty. Still, we had waited only a few minutes when Charlie’s electronic beeper beeped. Some maids working on the ninth floor thought they’d heard someone going up and down a hallway knocking on doors. Charlie used his passkey to open every room in the hallway—no guests had been registered in that particular wing—and searched the rooms without finding a sign of anyone. He looked up and down the stairs and asked the operator of the service elevator if he had brought anyone up to this floor. He hadn’t. Charlie’s theory was that the houseboys had been playing tricks on the maids. “But you never can tell,” he said. “Sometimes people check in, then sneak down to another floor and try to make advances on the maids.”

The rest of Charlie’s shift that day was purely routine. We made rounds, walking every floor from the top of the hotel to the bottom, checking doors, windows, and stairwells. “A lot of your hotel job is walking, just walking,” Charlie said. From time to time his beeper went off and he was called to the parking lot to see about a car with the keys locked inside or to the Century Room, where doors needed to be unlocked for a company dinner that evening, or to recheck rooms. This last is a tedious process. Each day the maids report which rooms are occupied and which are empty; frequently there is a conflict between the maids’ reports and the front desk records and those rooms need to be rechecked to see whether they’re empty or full. Charlie knocked on doors with his badge and identification held in front of him and calling, “House officer. Anyone there?” If there was no reply, he used his passkey to enter and inspect the room. “We were lucky tonight,” he told me on the elevator when he was finished. “Sometimes you go in a room and just then the guest gets back and you’re a stranger in their room. So you show them you’re the house officer and then they want to know what you were doing. You have to go into this long explanation. ‘Well, the maids make out reports . . .’ And the guest never understands.”

At 5:30 Charlie made more rounds. At 6:00 he ate dinner in the hotel restaurant. Back in the lobby a little later, he watched three teenage boys check in. When they’d gotten on the elevator he found out what room they were in. Supposedly only one of the boys was to be staying in the room. “They’re all going to stay in there,” Charlie said. “If they’re quiet, I’ll just leave them alone, but if they make trouble, I’ll kick the other two out.”

At 7:15 he noticed a tall man in an expensive plaid sport coat talking in a phone booth in the lobby. We had noticed the man, whose bright jacket made him very memorable, in the elevator several times earlier. “That’s odd,” Charlie said. “Why’s he phoning from there and not from his room? People do it sometimes, but we’ll have to check him out after a while.” Shortly after this phone call, however, the man went back to his room and didn’t emerge again until morning.

An hour later a desk clerk called Charlie over to tell him that a man by himself and without any luggage had rented a room for two and then gone back out.

“Dallas address?” Charlie asked.

The desk clerk nodded, then added, “And he used the name Johnny Jackson.”

Charlie laughed. “I guess that’s better than John Jones,” he said. But evidently Mr. Jackson’s plans met with some complications, for he never returned that evening. Meanwhile, as we continued rounds or sat in the lobby, Charlie pointed out the senile guest who falls asleep in the lobby, wakes up having forgotten that this is where he lives, and walks off into the night; the thin, middle-aged man who spends three hours in the bar each evening never saying a word to anyone, then staggers drunkenly through the lobby and out the door; the solitary old women who have lived at the hotel for twenty years or more.

Charlie was about to make his rounds again at 10:30 when I told him good-bye and went out to see what was happening on Commerce street. I headed for the Copper Cow and El Rancho Grande. Just across the street from the hotel, a short black woman in a heavy wool coat stood leaning against a building. “Hey, what’s your hurry?” she said. “You might be missing something good.”

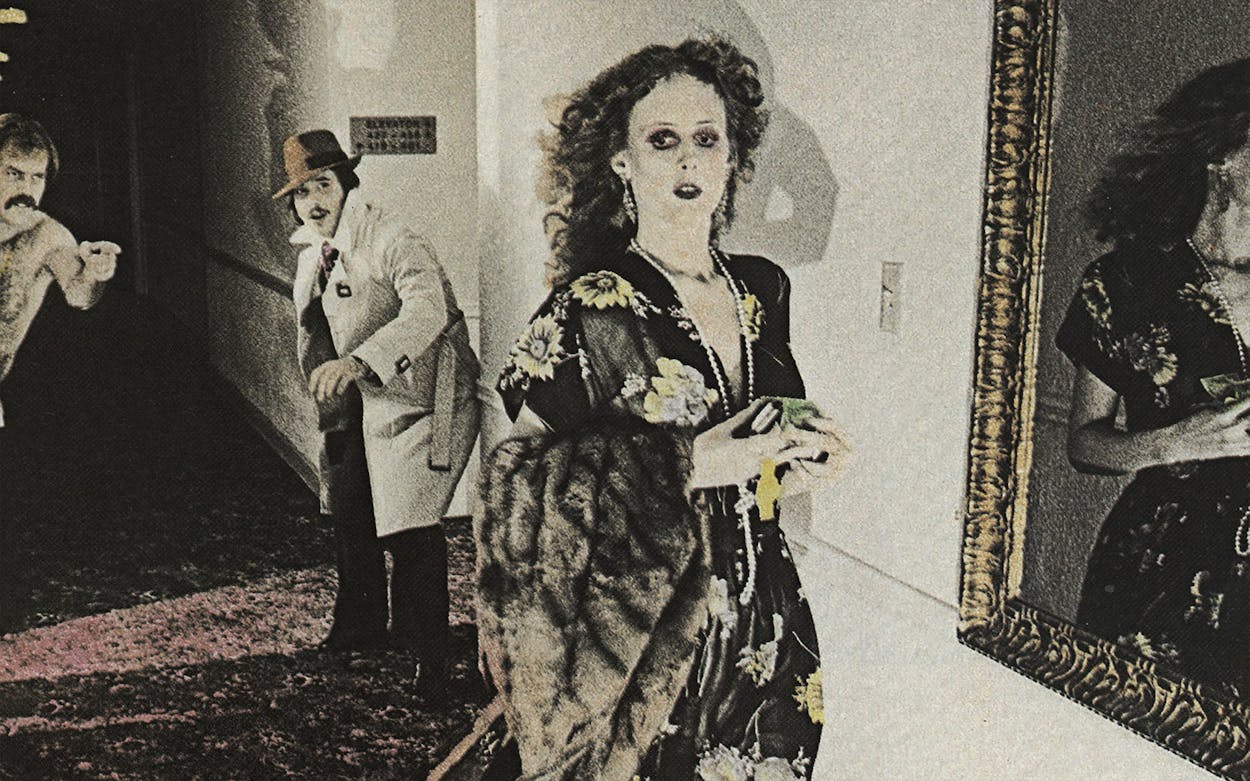

I waved back at her and walked on. Two patrol cars cruised past me before I got to the Copper Cow. Inside, the restaurant was far from crowded. Two fat men in industrial uniforms were having coffee. A reedy black man with a black Borsalino hat and black silk shirt with thin white stitching was sitting in a booth facing the street. He watched me expressionlessly as I turned toward the door that led to El Rancho Grande. A row of booths ran down one wall and there was a short bar on the other side, where I ordered a beer. Another man, wearing brown rather than black, but otherwise dressed in the same style as the man in the restaurant, sat at the bar. A third man, similarly clad, sat in one of the booths watching a television fastened high on the front wall. Three black women were drinking frozen margaritas in one of the booths. They were quickly joined by the short woman who had spoken to me on the street. They all looked to be in their very early twenties. Two more women stood in a small alcove just inside a glass door that led to the street. It was a quiet, decent enough looking place whose clientele at that moment happened to be two pimps, six prostitutes, and me.

Soon after I arrived, the two at the door disappeared back into the restaurant when a squad car stopped in front. The cop got out and came in. The bartender, a tall, slightly fleshy, sybaritic-looking man who was decked with large turquoise-and-silver rings, bracelets, and necklaces, said, “He’s in the rest room, officer,” and pointed airily toward the back of the bar. The cop went back there and soon emerged with a tall young man in blue jeans. His bushy blond hair was streaked with dirt and he was so drugged he had no idea where he was or what was happening to him. The cop led him slowly through El Rancho Grande and out into the squad car. The rest of the time the women came and went. They would stay outside in the cold for ten or fifteen minutes, then come back in to warm up. It was a slow night for business, but at 11:30, when I returned to the hotel to meet Bill Swafford, the night man, I saw two likely-looking customers, stocky young men in double-knit suits, come out of the hotel and head down Commerce.

Swafford is a short, muscular redhead who had spent sixteen years with the Dallas police before injuries from a wreck in a squad car forced his retirement. He had always preferred the late-night shift when he was a cop—“That’s when everything happens”—and still preferred it now after four years as a hotel detective. I followed him on another tour of rounds, checking doors from the top floor clear to the basement. We had to roust one derelict who had sneaked up to a dark landing on the ground floor with his bottle. The man moved wearily on without much complaint. We got back to the lobby just in time to see one of the women from the street step into an elevator with a man.

Swafford rushed across the lobby and flipped a switch in a pillar in front of the elevator bank. A rumble of static burst over a small speaker, then came a woman’s voice saying, “Sure, honey.”

“We can listen in on any of the elevators,” Swafford said. “Sometimes you can hear the room number that way. Sometimes you hear other things; you wouldn’t believe some of the things.”

The elevator stopped and we heard the doors open. “Seventeen,” Swafford said. “Come on.”

We grabbed another elevator and rode it to seventeen. When the doors opened, we stepped into the hallway. It was empty and completely silent. Moving quickly but quietly, we checked the hallways, peering around corners. Frequently Swafford would stop in front of a door and listen. Sometimes we could hear a television, other times nothing. Then we looked around a corner and down a short hallway. The door to the last room stood open. Motioning for me to be quiet, Swafford started tiptoeing down the hall. We were halfway there when he stopped and signaled me to turn around. Back down the hall, he said, “There’re a couple of guys from the vice squad down there. They’ve rented that room. That must be where she went.”

We walked back to the elevators, but while we were waiting Swafford heard voices in the room just opposite the elevators. We stood near the door. “I’m just doing this for a while,” a woman said. “I moved here from California with my girl friend. I’m trying to get enough money to go back.”

“You don’t like Dallas?” a man said.

“Oh, sure, honey. It’s okay . . .”

At that moment the elevator doors opened and the two stocky young men I’d seen earlier got out. Swafford motioned for them to follow him around the corner. What I had taken for two likely customers were men from the vice squad. Swafford told them what was going on in the room. They took our position listening at the door. “See, if they hear money mentioned,” Swafford whispered to me, “they can go right in and make an arrest.” We got on the elevator going down, with the vice squad still listening at the door.

In the lobby, Bill Swafford began to make notes for his first hooker report that night. There would be several others before the night was over, but none that involved racing into elevators and slipping quickly through hotel corridors. Usually all this work is routine, but there are times when the situations get tense or violent, and for those Swafford carries a pair of handcuffs and a small revolver. “Once,” he said, “I chased this girl out of the hotel, and her pimp came back and threatened me right here in the lobby. I followed him back outside and he went around the corner. I waited out front on the sidewalk for a while, and sure enough here he comes down the street in his Cadillac. I put my hand inside my jacket on my gun and stood there. He stopped. His window was rolled down. I knew he had a gun and he knew I had a gun. We looked at each other for a while. I was just waiting for him to make a move, but nothing happened. He just drove on.”

Swafford shrugged and leaned back in his chair. We were sitting in the lobby in two stuffed chairs that commanded a view of the main entrance and the long corridor that led to the parking garage. It was late, only an hour or so before sunrise, and no one had come through the lobby for a long time. During his shift, in addition to the hooker reports, Swafford had politely quieted some pleasantly drunk guests whose loud jokes were carrying out of their room and down the hallway; he had made rounds of the floors; he had gone out on the roof to see the night sky; he had gotten sandwiches from the refrigerator and made toast for the desk clerks and the telephone operator; and he had checked hundreds of locks—on doors, cash registers, liquor cabinets, refrigerators. “I like this work,” he said, sitting back in the chair. “I like the night. I like this hotel. And I like trying to keep some of these silly people from getting rolled.” And, with all the guests asleep in the hotel and the streets dark and empty outside, Swafford sat watching both entrances to the hotel.

- More About:

- TM Classics

- Longreads

- Hotels

- Crime

- Dallas