This story is from Texas Monthly’s archives. We have left the text as it was originally published to maintain a clear historical record. Read more here about our archive digitization project.

Scholars conversant with the Superman comic books will recall the concept of the Bizarro World, a mirror image of Earth populated by beings with cracked faces who say “Me happy” when they’re miserable and “Me want to take a walk” when they plan to sit down and watch the radio or listen to TV. It all had something vaguely to do with matter and antimatter and the idea that everything has its precise opposite somewhere in the vast wastes of the universe.

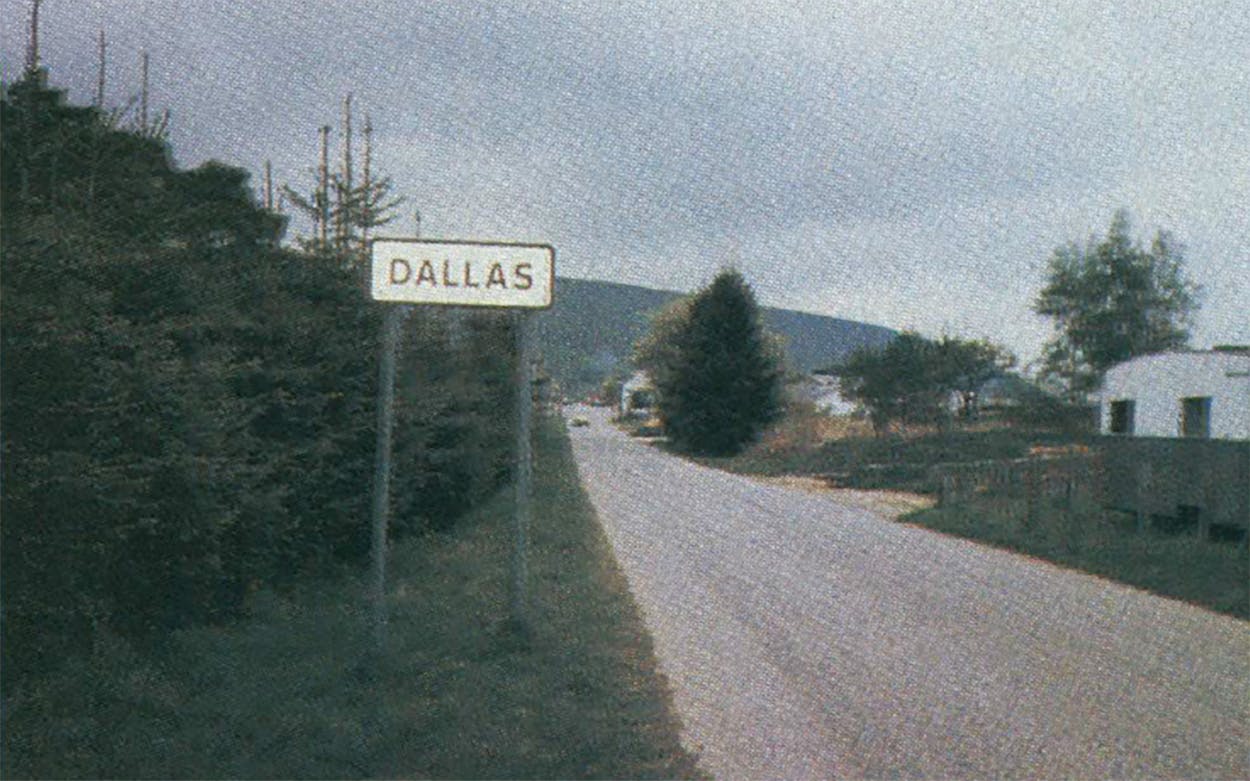

One need only travel about five thousand miles to find Dallas’ precise opposite. It’s called Dallas, of course, and it’s a charming town of perhaps two hundred souls, located in the northern reaches of the Scottish Highlands. Deciding which Dallas is real and which Dallas is Bizarro is a matter of taste, but whatever is true in one Dallas is invariably out of the question in the other. One is big, growing, and obsessed with growing faster. The other is tiny, shrinking, and quite content with its lot. One lives to wheel and deal, the other is happy to sit back and watch. One’s too hot, the other’s too cold. One has the flying horse, the other has the killer geese of Rafford. Big D keeps boasting that it’s the city of the future, but little d plays by entirely different rules. “This is like the village that time forgot,” says Albert Gray, proprietor of the six-room Dallas Hotel, the lone eatery, drinkery, and hostelry in Dallas, Scotland. “Life just goes on, and things take care of themselves.”

Getting to little d is about as easy as finding the Loch Ness monster. My suggestion is to take the spectacular drive through the Scottish Highlands past Loch Ness to Inverness, then head east past Nairn to Forres. Go past the roundabout into town and park in front of the Forres Gazette. If you’re lucky, reporter Caroline MacKenzie will take you out to little d. Otherwise, get explicit directions. On your way south from Forres you’ll pass the now closed Dallas Dhu Distillery. Be sure to look out for the killer geese of Rafford, which guard the outskirts of Dallas like medieval sentries. On my trip with Caroline they blocked the road and tried to bite the tires off her red Citröen, which she drives like a Grand Prix contestant. “The geese make very good watchdogs,” she said helpfully.

Dallas, Scotland, is a bit older than Dallas, Texas. Folks in little d say the name is from the Gaelic for “watery valley.” One reference says it means “the house in the meadow.” You can get different historical accounts from almost anyone you talk to in little d, but the town’s official existence dates back to the twelfth century, when Scotland’s King William the Lion granted the lands at Dallas Moray to one William de Ripley, whose son became Sir William of Dallas. A Dallas family tree presented by the folks of little d to the ones in Big D traces their ancestry through such notables as Thomas de Dollays, John de Dolays, Hendry de Doles, and William Doles (I, II, and III) to George Mifflin Dallas, the former U.S. vice president. Clearly, spelling wasn’t the family’s strong suit. Whether Big D was named for the former vice president is a matter of some dispute—some historians lean toward Commodore Alexander Dallas. But everyone in little d is fairly confident that whoever gave Big D its name can be traced back somehow to the original denizens of the watery valley. The town has been moved several times, and part of it now stands on what used to be a huge lake (it was drained to provide more arable land). Around 1790 the town was moved away from the River Lossie to its current location. Memorable landmarks include the ruins of Torchastle, once the local castle, and Dallas Lodge, the home of the Houldsworth family, who’ve been the local landowners for most of this century. Dallas Lodge was designed by a fellow known as the Wizard of Gordonston, who was so terrified of the devil that he had the house built in a horseshoe shape so the devil couldn’t lurk in corners. Sounds like a concept with potential on Greenville Avenue.

Dallas is not exactly booming. The school, which had three teachers and about seventy students in the thirties, has one teacher and eight students now. The town proper consists of a main street lined with buildings of weathered native stone. The only store is D&E Hay, general merchants and licensed grocers. But Dallas also has one gas station and a rather mystifying car dealership where one can get such exotica as Polish automobiles. In the past three months the Forres Gazette has managed to find only two newsworthy events in town: the departure of butcher “Big Robbie” for Australia and the retirement of the couple who ran the post office. Dallas doesn’t get much attention from its neighbors, who usually say it’s “a lovely, wee place,” mention how awful its winters are, and generally view it the way people in Odessa view Wickett.

No one seems to mind, though. Big D may exist in a whirl of schemes and ventures, but little d sits back in an affable mire of contentment. Not that there aren’t things to do. One favored fair-weather recreation is to go up in the green hills and dig for peat, which will be used as next winter’s heating fuel. “It’s quite exhilarating up on the moor, away from everybody, cutting your peat,” enthuses Andrew Bailey, whose wife, Edwina, is the new postmistress. There’s the Houldsworth Institute (little d’s answer to the Bronco Bowl), which hosts youth groups, indoor shooting ranges, bowling, barn dances, and local civic meetings. “All the farmers like to come down from the hills and have a real good hooley,” Bailey reports. There’s the annual Christmas party and the annual summer picnic, for which the entire town makes sausage sandwiches and other goodies, loads into buses, and goes to the beach at the nearby Moray coast. And the town’s biggest hooley is its annual Dallas Gala, a weeklong summer celebration that brings as many as four thousand people from neighboring towns for helicopter rides, footraces, soccer games, whist, bingo, and special extravaganzas like last year’s much-acclaimed display of some thirty tractors.

There has even been a little of that Big D entrepreneurial spirit of late. Two of the younger Houldsworths (Mark and Simon) and Tim Griffiths, a dentist who practices in nearby Elgin but lives in Dallas, have been working for some time on marketing a brand of Dallas Scotch in the U.S., whiskey being to Morayshire what cars are to Detroit. They’re still not sure whether to call it Dallas or Dallas Torchastle, but they have a blend of eight-year-old Scotch distilled by Gordon and MacPhail in Elgin all prepared and ready to go. They hope to have three hundred cases of 12 one-liter bottles each in Texas in time for the Republican convention. If that works out, they’d like to add a fine single-malt whiskey as well, with part of the proceeds going to the Houldsworth Institute, which—in Big D style—is supported entirely by private funds, something of a necessity since little d has no mayor, council, or any other form of local government. “We don’t like to sit on our laurels and let others do things for us,” says Simon Houldsworth. He’s been to Dallas, Texas, and maybe some of it rubbed off.

If Big D is easy to admire but hard to love, it’s almost impossible not to be seduced by little d, which is about as idyllic and friendly a place as you’ll ever find. The folks there watch Dallas, of course, the most recent episode often being a prime topic of conversation at D&E Hay. The denizens of little d seem to have an almost clinical fascination with J.R., like birdwatchers who’ve come upon a new and utterly weird species. That’s probably at the heart of the case for little d. The town does have its own J.R., one J. R. MacKenzie, a retired distillery worker with no known Machiavellian tendencies. But questions about Ewing-like residents or particularly crafty movers and shakers draw only delighted gasps, as if you’ve just asked if there’s anyone in town with four heads.

“Oh, no, nothing like that here,” says Angus MacKinnon, a retired gamekeeper at the Dallas Lodge. “These are just friendly people, old-fashioned, behind the times, you might say.” The future, of course, belongs to the zealous wheelers and dealers in Big D, not the affable peat crunchers in Morayshire, but if there’s a perfect world out there, Bizarro or otherwise, it probably has a little bit of both Dallases.

- More About:

- TM Classics

- Dallas