This story is from Texas Monthly’s archives. We have left the text as it was originally published to maintain a clear historical record. Read more here about our archive digitization project.

At the Taylors bookstore on Belt Line Road in far North Dallas, an entire shelf has been set aside for books pointing the way to easy riches. Some urge a career in sales, or stocks, or gold, but by far the majority tout real estate. You can learn how to Start Right in Real Estate; Turn $1000 Into Five Million in Real Estate; Boost Your Earnings in Real Estate; Become Financially Independent in Real Estate; or, for the lazy, Get Rich in Real Estate While You Sleep.

As if to prove the point, the bookstore itself is in the heart of one of the hottest real estate plays in the country. Known in the trade as the Magic Corridor, it stretches north along either side of Preston Road from the LBJ Freeway out to the Collin County line and even beyond. Five years ago all this was prairie. Now there is a Neiman-Marcus here, a Sakowitz from Houston, a sprawling mall with an ice skating rink, high rises, townhouses, six-lane streets. Just do what the books say and you can’t lose.

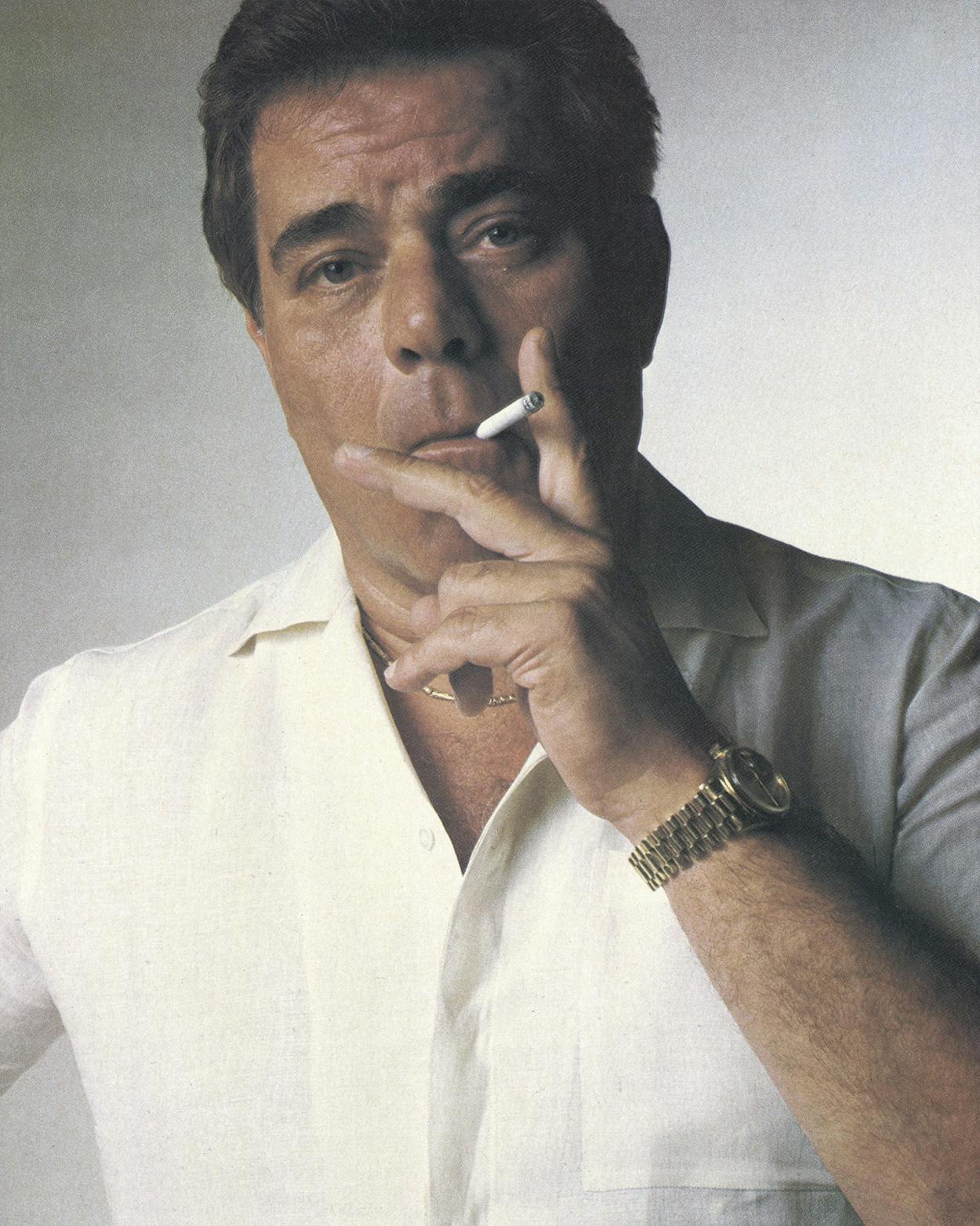

But you can. Ron Monesson did. Today, fifty years old and out of a job, Monesson spends his days in a rented Preston Road townhouse (the sign advertising the project calls them villas) reading not real estate books but a volume titled Lasting Relationships. Less than a decade ago he was one of the foremost residential developers in Dallas, praised for his creativity and vision as the first to concentrate on townhouses instead of apartments and traditional freestanding homes. He started in 1966 with a stake of $2500, and by 1973 he had parlayed it into an empire that operated in four states. At the height of his success, in 1973, his net worth (on paper) exceeded $9.7 million. He had 330 employees, a Mitsubishi MU-2 propjet, prime landholdings, countless building industry awards, and a restaurant that was the standard by which all others in Texas were judged. As meteoric as was his rise, so was his fall: by 1976 he had filed for bankruptcy and his wife had filed for divorce. Though he talked his way into a second chance in both cases, in the end he lost both his business and his marriage.

By the standards of contemporary Texas, Ron Monesson is a failure. He is in a category with the carpenter in Sherman who until recently was a major builder, the janitor in Richardson who once amassed paper millions in DFW airport land, and everyone else who seeks refuge in the bankruptcy courts in the federal building in downtown Dallas. In enclaves like North Dallas, it is part of the mythology that anyone with vision and ambition and the willingness to work can make money. North Dallas abhors failure: the prevailing ethos is that those who succeed do so because they are somehow better—more skillful or more virtuous—than those who do not.

In the early days of his career as a real estate developer, Ron Monesson seemed to be a case in point. He had brains and a willingness to take risks, and it paid off. He won big. Then he lost big, and his smarts began to look like conceit, and his gambler’s instinct like excessive incaution. The truth is that what makes someone succeed is quite close to what can make him fail, and that in a betting game like North Dallas real estate, everybody can’t win. Monesson’s is a story of the dark side of the boom days of modern Texas—of how horribly wrong things can go even here, and of how completely things going wrong can change your life.

Going Up

In the early spring of 1972 an unusual advertisement appeared in both Dallas newspapers. How Much Longer Do We Have to Wait for a Really Superb Townhome Environment? it asked, and underneath came the answer: Seven More Days. Everything about the ad represented a departure from the typical housing promotion of that time. In the first place, it concentrated more on the environment than the townhouse, an approach known as selling lifestyle instead of shelter. Today this is standard practice, but nine years ago it was a radical new marketing idea. Another oddity was the location of the ad—not in the traditional spot, the Sunday real estate section, but rather up front with the news and the big department store advertisers. Finally, a slick, expensive advertising campaign for high-density housing was unusual in itself, since the conventional wisdom among Dallas developers then was that townhouses were for people who couldn’t afford real houses. It was a blue-collar market, more appropriate for Mesquite than North Dallas. Still, on a rainy Sunday afternoon, the ad brought almost a thousand people out to LBJ and Abrams in Northeast Dallas to look over a development known as ChimneyHill.

ChimneyHill was Ron Monesson’s brainchild. Townhouses were not in favor, and many lending institutions wouldn’t even advance money to build them. But then, not many builders wanted to try. Most affluent buyers didn’t even know the difference between a townhouse and a condominium (in a townhouse, the owner has title to an individual lot and building, except for common walls; in a condominium, ownership includes only one’s interior living area, while the building and grounds are owned jointly by all occupants). The typical townhouse project was a small, made-over apartment house with units that all looked alike. But ChimneyHill was huge—51 acres, with 101 more to be developed—and had been designed to mask similarities and play up differences. Colors, textures, designs, roof materials, and setbacks had been varied to make the development look as if it were made up of separate houses.

What’s more, ChimneyHill was already taking shape. Usually, condominium and townhouse developers start selling units before the first slab is poured; the buyer sees only a diagram or a scale model. At ChimneyHill, the community structures —clubhouses, tennis courts, swimming pools—had already been completed, and 52 dwellings were under construction. And the prices started at—those were the days—$28,800.

This was Ron Monesson’s first big moment, and it had been a long time in coming. He was born in 1930 and grew up in the town of Lakewood, New Jersey, where his father was a manufacturer of pickle products. He played defensive end for Tulane in 1948 and 1949, a time when it was a major football power. After college Monesson joined the Air Force, and while stationed in San Antonio, he went to St. Mary’s University at night to earn a law degree. Following his service tour, he joined a firm in San Antonio and got his first big break when he won an important income tax refund case. The client was so grateful that he gave Monesson a cash bonus (as a young lawyer, Monesson was on salary and wouldn’t have shared in the fee) that was generous enough to enable him to quit the firm and open his own office. His practice leaned toward real estate law, thanks to a major client he picked up as the result of a recommendation by the dean of the law school, but Monesson couldn’t tolerate doing deals that made other people rich. After a year and a half, he closed up his law office to learn the real estate business from the inside.

For his apprenticeship he returned to New Jersey and joined the East’s second-largest homebuilder, Robilt. The firm specialized in single-family tract houses, thousands and thousands of them. As vice president in charge of planning and development, Monesson learned about dealing with banks and subcontractors and (this being New Jersey) corrupt officials—from the cop on the beat who had to be taken care of if you wanted to park a cement truck in front of a job site to the mayor who kept a schedule in his desk of how much he had to be paid based on the total cost of a project. Monesson had given himself three years to learn the business, and he stuck to that timetable. By the end of his stint, he had come to two conclusions: first, that the East was dying economically and the better opportunities were in Texas; second, that the future of residential housing did not lie in cheerless subdivisions crammed with single-family houses and far removed from central cities. He decided he ought to be in a major city, and he picked Dallas over Houston because he considered it more civilized and cosmopolitan. He moved there in 1964.

Monesson started out by selling commercial real estate. He was a natural at sales—big, gregarious, opinionated, persuasive almost to the point of being overbearing, and totally sure of himself—but his real interest was development. He didn’t have the capital or the credit, but, as in San Antonio, luck was with him. Morris Jaffe, a leading Dallas lawyer who died in 1980, considered Monesson something of a protégé. When a wealthy client named A1 Rabiner moved to Dallas from Iowa in the late sixties and wanted to invest in real estate, Jaffe arranged a meeting with Monesson.

Real estate development can follow one of two financial paths: it can be set up to produce income or to shelter income. A residential development like ChimneyHill is designed for quick profit: buy by the acre, sell by the lot. That was not the sort of thing Rabiner was interested in at all. The last thing he needed was more income out of which to pay Uncle Sam 70 cents on the dollar. Instead, he wanted to borrow heavily—95 to 100 per cent financing—and use the huge interest payments as a deduction to reduce his taxes on other income. His aim was to keep the cash outlay small; his profits would come later (and at a lower tax rate) in the form of capital gains when he sold the property after holding it for several years.

That kind of deal wasn’t what Monesson had in mind, but one investor is better than none, and so the two men formed a partnership. Monesson converted his garage into an office and put his wife to work as bookkeeper and business manager. Rabiner borrowed the money, and Monesson bought the land and built (so to speak; he says he couldn’t nail two boards together if his life depended on it) apartments and shopping centers: the Creekside North Apartments near Coit and LBJ, the Playhouse Apartments in the Oak Lawn area, a shopping center in Denton and another in Arlington. The partnership made some money, but Monesson pressed to do bigger deals. He is a hard man to say no to, and eventually his partner grew weary. “He’s too strong for me,” Rabiner told a mutual associate, and in late 1969, after four years, the two parted ways. The split was friendly, and its terms were highly advantageous to Monesson: he bought Rabiner out for $72,000 cash, plus assumption of debts including $600,000 in unsecured loans. That arrangement required the approval of the lender, who was losing a rich debtor and gaining one whose main assets were self-confidence and enthusiasm, but it must have seemed an acceptable risk. Monesson was a man on the way up, he was full of ideas, he couldn’t miss.

On Top

With the immediate success of ChimneyHill—168 units sold in a little over a year, grossing more than $7 million—Ron Monesson became the sort of minor celebrity that a successful developer is in Dallas. The Dallas Morning News ran a feature article about him. His work was cited in Fortune magazine and two housing industry journals. People he hardly knew invited him to their cocktail parties, and the Dallas Civic Opera, Thanksgiving Square, and the Baylor Medical Center asked him for contributions.

It was the same story in the real estate business, Trammell Crow, Dallas’s leading commercial developer, used Monesson’s name and picture in his own newspaper ads to promote the office complex where Monesson’s company was headquartered. Banks called him, unsolicited, offering to lend money. So did investors. Real estate brokers checked to see if he wanted in on deals. Monesson even got calls from people purporting to be agents for sheiks, though he never did business with any of them. He trademarked the ChimneyHill name and made plans to build similar developments in Austin, Indianapolis, Tulsa, and Macon.

Inside the building industry he had a national reputation. Builders are quick to throw around terms like “innovative” and “creative” to describe (or disguise) their work, but in truth, homebuilding is one of the stodgiest industries around. Even the simplest innovations, like substituting plastic pipe for cast iron, take years to gain acceptance. Lenders are conservative by nature, and so are planning and zoning commissions, with the result that whatever everyone else is doing tends to keep on being done.

Monesson broke the pattern. He foresaw the problems with commuting when gasoline was still selling for 31 cents a gallon; he anticipated the need for land planning when other developers thought cul-de-sacs were a daring departure from grids; he understood the importance of high-density housing when land was still cheap. He took his architects and other top employees on a housing tour of California and returned convinced that the West Coast emphasis on lifestyle would reach Dallas. On all counts he was right. He had found a new market, and other builders wanted in. Monesson had three merger offers from larger building firms, but he turned them down. “I don’t care about becoming a giant corporation,” he told a reporter at the time. “What I really want is to be recognized as the best.”

It is possible to see, with the full benefit of hindsight, one of the causes of Monesson’s downfall emerging at this point: his ego. Successful developers are by nature a supremely self-confident lot, but the particular form that Monesson’s egotism took was a desire to be personally recognized as a man who was more interested in quality and innovation than in making money. His disregard for the rest of the housing industry bordered on contempt. He was so sure he was right that he built himself no safety nets. He never incorporated his company but kept it a sole proprietorship, feeling that corporations can’t make entrepreneurial decisions, and he never delegated much authority within the organization either. He lived well—drove a new Mercedes, took his wife to Europe every year, acquired a taste for $100-a-tin caviar—but he never built a big house, the way most developers do in order to have an asset that is protected from creditors in case things go wrong. He was maximally exposed, maximally confident, more and more in the limelight.

After ChimneyHill’s initial success, his advertising campaigns took on a self-promotional tone. See What Imagination, Discipline, and Money Can Do, read one. Another, quoting Monesson, carried the headline “When I Walk Through ChimneyHill, I Am Filled With an Enormous Feeling of Accomplishment.” Even Monesson’s next project seemed designed for recognition as well as profit. It was called the Highlands of Kessler Park, and what got all the attention was the fact that Kessler Park was in Oak Cliff, a part of Dallas that was not prime material for anything except white flight. No North Dallas developer had ventured south of the Trinity in years. But once again Monesson was right: originally priced lower than ChimneyHill, the Kessler Park units have a higher resale value today.

Then Monesson moved on to a new arena entirely. When a business associate told him in May 1972 that a Betty Crocker family restaurant and bakery on LBJ was available for $525,000, Monesson snapped it up before it went on the market. His original intention was to move his real estate office there, but the more he thought about the restaurant business, the more the idea appealed to him. He began talking about “the masculine dream of owning your own bar or nightclub,” but what he had in mind was hardly a corner tavern. He wanted, he said, ‘‘a restaurant equal to any in the world.”

He talked over the idea with Helmut Horn, a stylish German immigrant who was then food and beverage director at the Fairmont Hotel. Horn’s duties included overseeing the Pyramid Room, then unchallenged as the state’s most ambitious haute cuisine restaurant, and Monesson was a frequent patron there. The two men had gotten to know each other when Horn had bought a townhouse at ChimneyHill, and their friendship had been cemented over chocolate cake: one night at the Pyramid Room, Horn asked Monesson how he had enjoyed the meal, and Monesson, who had acquired a connoisseur’s appreciation of fine food and wine, gave him a mild but informed criticism of the cake. The next day a doorman from the Fairmont appeared in fulldress uniform at Monesson’s door with a whole cake and a message from Horn asking Monesson to keep tasting until the restaurant got it right. It took Monesson, who knows a good deal when he sees one, five cakes before he was satisfied.

Horn was ready to leave the Fairmont; he was discouraged because the Pyramid Room, despite its exalted reputation, had failed to attract a local clientele. He agreed to join Monesson as general manager in charge of day-to-day operations of the new restaurant, which would be called Oz. But before the restaurant opened, the Hyatt hotel chain offered him an irresistible job in Hong Kong: managing its food and beverage operations in the Far East. He told Monesson he’d be gone only one year and suggested hiring his assistant at the Fairmont. But Horn never returned to Dallas, and Monesson never attained the same rapport with the assistant.

Nevertheless, when Oz opened its doors in May 1973 it met with the same sort of instant success as ChimneyHill. Monesson enhanced the restaurant’s mystique by giving orders to take only drop-in trade for the first two weeks; anyone who called to make reservations during that time was to be told that the place was full for the evening, even if every table was empty. The gambit worked: after two weeks, memberships (since Oz was located in a dry precinct, it was a private club with an annual membership fee) were as sought after as Cowboys tickets, and before long Oz had six thousand members.

For a chef, Monesson acted on Horn’s advice and hired Jean LaFont away from Ernie’s in San Francisco. Most of the captains and waiters were imported from Montreal. A good deal of the food was brought in as well: butter and cream from New York, lobster from Boston, Dover sole from France. He also had a club within a club, known as the One Hundred of Oz. On Monday nights, when the restaurant was closed to the public, Monesson served special dinners for $100 a person that featured items like the finest Alsatian pâté, flown directly from Strasbourg to the restaurant; truffles as big as golf balls, carried in baskets by chefs imported for one night; wines unavailable in any other restaurant in the world, acquired by Monesson from the private collections of the best châteaus. He even brought in experts from Bordeaux to give wine seminars.

It was just like ChimneyHill. Oz—and Monesson—got national attention, only this time it was from Time and the Wall Street Journal, not industry publications. Once again Ron Monesson had done what he had set out to do, what others had told him couldn’t be done, and even if the restaurant operated at a loss during all but two months of its first year, that didn’t really matter: everything else was doing well, wasn’t it?

Going Down

“When it’s going great guns,” Ron Monesson says, “every decision you make is right. You just feel you’ve got the opportunity to continue indefinitely and defy the trends and the cycles.” So it was for him as 1974 began. He had pushed all his chips to the center of the table. He kept no cash reserves. He held on to properties—shopping centers and apartments—that he could have sold to stay liquid. His overhead was $200,000 a month. Oz was losing money. And a very bad year for the real estate industry was just beginning.

Meanwhile, Monesson was looking ahead to what would happen when ChimneyHill was sold out. He would need other land. So he began acquiring property. He bought some land in Grapevine near the DFW Airport and some near Highland Park, and he optioned 444 can’t-miss acres on Preston Road near the Preston Trail Golf Club. He went to homebuilders’ meetings and sought out those who were down on their luck and looking to dump property quickly. He borrowed and borrowed again, going $40 million into debt, and every time he went back to the banks and the savings and loans, interest rates were a little higher. But it didn’t really bother him, for ChimneyHill was a money tree in full bloom. He read the predictions of a slump in the housing market in 1974, but, he recalls, he didn’t believe it could happen to him. His product was too good, too much in demand, too well marketed. For most of the industry, 1973 had been a down year. For ChimneyHill, it had been a great year: 147 units sold, more than $6 million grossed.

But ChimneyHill had a bad year in 1974, and Monesson’s empire couldn’t withstand the shock. His business had a narrow base: the apartments left over from his partnership days weren’t designed to generate cash, and other development projects like Kessler Park weren’t big enough to make up the difference when ChimneyHill sales declined. It wasn’t much consolation, but part of his trouble came from his own success. He no longer had the quality townhouse market to himself; he had blazed the trail for his competition. Worse, he was also competing with himself: some of the original buyers at ChimneyHill had put up their townhouses for sale. They could sell their old units for a substantial profit and still undercut the prices Monesson was charging for new construction. His marketing campaigns continued to lure people out to the development, but many were sidetracked by the old owners’ For Sale and Open House signs.

When sales started to fall off, the only remedy was belt-tightening, but Monesson ignored warnings to cut his work force and reduce his overhead, as prudent builders usually do in hard times. He was convinced that he was immune to the downturn, certain that the trend would reverse itself, and so he kept on expanding. Instead of concentrating on financing, he kept his hand in every aspect of management, handling everything from zoning cases to the structure of land deals to the details of advertising campaigns. He was constantly off to Indianapolis or Tulsa, or greeting guests at Oz, or looking for more property. He was ready for a new triumph that would testify once more to his courage and vision.

By early 1975 the company could no longer pay its bills, even though on paper Monesson was a rich man. All his money was tied up in land, and much of that land was held in joint ventures, so Monesson couldn’t sell it unless his partner agreed. He did manage to sell off some property, but not enough to make ends meet. As he had learned on the way up, a seller in distress does not get his price.

At first Monesson acted with characteristic boldness: in February he called his unsecured creditors—building industry subcontractors and accounts payable—to a meeting at the Marriott Hotel near his office and offered to pay 50 cents on the dollar. Some took the settlement, but most, beguiled by Monesson’s self-assurance, decided to ride it out. “We thought if anyone could turn things around,” says one of his former subcontractors, “it was Ron Monesson.”

It was the secured creditors—the banks and the savings and loans that had advanced him the money to buy land and develop it—that were Monesson’s main worry. All were protected by liens on his property. They could ruin him by declaring the entire loan due (the payments Monesson had skipped were interest only) and, since he couldn’t possibly pay off the principal, foreclosing on the property.

As a lawyer, Monesson knew all too well that Texas has some of the harshest foreclosure laws in the country. A creditor can force a sale on the courthouse steps with scant notice and without setting a definite time. Since no one else is likely to know about the auction, the lender is the only bidder. There is nothing to prevent him from bidding, say, $1 on a $1 million debt, getting the property free and clear, and then filing a deficiency judgment against the debtor for the remaining $999,999. The only way to stop this legalized larceny, short of coming into a windfall to pay off the debt, is to file bankruptcy.

Monesson’s chief lender, First Texas Savings, knew all this, of course. Just as debtors fear foreclosure, creditors are leery of bankruptcy. At the very least, bankruptcy means months, even years, of delay. In the absence of outright fraud, bankruptcy judges are more protective of both debtors and unsecured creditors than of secured creditors; they know anyone with a lien will come out all right in the end. Judges are often reluctant to give secured creditors their property quickly, particularly in real estate bankruptcies. If, for example, First Texas was allowed to take back the unsold portion of ChimneyHill, not only would Monesson be finished but also his unsecured creditors would have little hope of getting paid. Bankruptcy cases often result in letting the debtor stay in control, under court supervision, with a plan to pay off the creditors. First Texas had a no-win choice of dealing with Monesson in charge of a sick business or dealing with Monesson in charge of a bankrupt business; for the time being, it decided its interests lay with the former. So Monesson and his bankers spent most of 1975 playing a game of bluff, each threatening to take legal action that neither really wanted to initiate.

At the negotiating table Monesson was the same as ever: tough, shrewd, irrepressible; as one adversary put it, “He never dragged his nose in his beard.” Monesson’s message to First Texas, and indeed to all of his creditors, was “Look, I’ve made you a lot of money over the years; just see me over this rough spot and I’ll be back on top.” His hole card was a $5 million usury claim against First Texas, based on a state law (since voided by Congress) that allowed lenders to charge no more than 10 per cent interest. With fees and points added in, First Texas was arguably exceeding the limit. At least, someone at First Texas must have thought so, because Monesson had received a contrite letter apologizing for miscalculations in language that included the compromising word “usurious.”

But away from the combat arena, the strain of failing was exacting its toll on his personality. Few things in this world are more oppressive than a debt that can’t be paid. The clock never stops running. Every day that passed added another $1000 to Monesson’s interest obligation on ChimneyHill. A night’s sleep cost him more than $300, but he seldom got it; creditors started calling at 5 a.m. Monesson’s behavior followed a classic pattern. He stopped answering his mail and returning his phone calls. He began spending more and more time out of the office.

Because his wife knew the business so well, home was no escape; he began dating the nineteen-year-old front desk manager at Oz (it was no fling, however—six years later they’re still together), and his marriage fell apart. Always a sports fan, he started betting heavily on games and spent hours poring over tout sheets. And there were the painful exchanges with associates who had become creditors. “How can you do this to an old friend?” Monesson asked one. “How can you do this to an old friend?” came the reply. A couple of times Monesson lashed out violently at subcontractors.

Finally, in May 1976, First Texas made its move—right for the throat. Just when Monesson thought he had negotiated an agreement with the savings and loan for continued financing, the loan officers hit him with a notice that they intended to foreclose. They had run out of patience, and Monesson, who had been selling off property to stay afloat, had just about run out of assets.

As if to let Monesson know that this fight was for keeps, First Texas’ lawyer (who no longer represents the organization) took the unusual step of going out to ChimneyHill and rounding up a posse of unhappy owners. “It was a lynch mob atmosphere,” says the lawyer who represented Monesson at the time. The complaints were mostly petty, ranging from sprinkler systems that didn’t work to heating bills that were higher than salesmen had promised; most were later thrown out of court. But they were the last straw: on June 1, 1976, with 49 lawsuits against his company—all of which he was personally liable for—and First Texas on the verge of burying him in deficiency judgments for the rest of his life, Ron Monesson filed for bankruptcy.

Hitting Bottom

The American debtor has come a long way since colonial days, when Connecticut’s Newgate Prison housed as many as one hundred unfortunates. Newgate was an abandoned copper mine accessible only by a ladder; inside, the debtors’ feet were fastened to iron bars and their necks were chained to beams in the roof.

Since passage of the federal bankruptcy law in 1898, the advantage has shifted steadily to the debtor, and today the magic word is “rehabilitation.” Fewer and fewer debtors are choosing straight bankruptcy, which calls for liquidation of their holdings and apportionment of the proceeds among their creditors. Instead, business debtors, under chapter 11 of the federal Bankruptcy Code, can reorganize without ever going out of business. This is known as being a debtor in possession, and in most commercial bankruptcies it is routinely authorized. Monesson wanted to do that, and had his bankruptcy occurred two years later, a change in the law would have been on his side. But the old law was not so clear, and First Texas was determined to get Monesson out of ChimneyHill.

By filing bankruptcy, Monesson blocked First Texas from foreclosing under the confiscatory state law. Any sale would require a judge’s approval and would have to be at a fair price; no courthouse-steps chicanery would be allowed. But when he applied to become a debtor in possession, his failure to accept his difficulties at an early date—his tenacity, his self-confidence, his pride, his ego —worked against him. He had waited too long to file bankruptcy; he had no cash and few unencumbered assets. He couldn’t sell anything at ChimneyHill, because he didn’t have the money to finish construction. “You can stop us from foreclosing,’’ First Texas’ lawyers told the judge, “but the one thing you can’t do is make us lend him money.” So Monesson’s request that he be allowed to stay in business was denied and the property was sold—to First Texas, for the amount of the debt. First Texas finished the project along Monesson’s lines and, as he said he would have, made money in the end.

Monesson was down to his last resource: the usury suit. After almost a year of negotiation, he and First Texas reached a settlement: Monesson would drop the suit and First Texas would lend him the funds to get a new start in building. But when Monesson showed up to borrow the money, he found that First Texas would agree to finance only individual houses, not projects like ChimneyHill. He was back at square one: a builder, not a developer; selling shelter, not lifestyle. And worse, he had to build single-family dwellings, something he didn’t even believe in. To add to the humiliation, First Texas would not allow him to draw money in advance, as almost all builders and developers do. Instead, money was paid on invoices, plus 5 per cent as Monesson’s pay, averaging around $1750 a month. He was small-time.

Monesson built seven houses; but his heart wasn’t in it. He had no employees, of course—just subcontractors that he supervised, and he sometimes neglected to do that. All during the construction period he was tied up in what grew into a bitterly contested divorce case (the property division was the only issue; as often happens to husbands who appear to have high earning capacity, Monesson ended up with most of the debts, and his wife with the few remaining assets), and the houses took much too long to complete. All the while, the interest meter was running. He sold off his last piece of land, a strip adjacent to ChimneyHill once designated for commercial development, but that only postponed the inevitable. In the fall of 1979, First Texas foreclosed again, took the houses back, and left belly up for the second time. Not a trace of his empire was left.

Now

Ron Monesson drives as if he were carrying a football. He plunged through a line of cars in order to reach the entrance of one of the more expensive new developments in North Dallas and accelerated down the short street. It was a sweltering afternoon this past summer, and Monesson was giving me a builder’s tour of high-density housing.

He was driving a baby-blue Coupe de Ville and wearing a Rolex watch, rather nice trappings for a man not yet discharged from bankruptcy. But he had bought the car used, from a friend’s mother, and the watch was sixteen years old, and he hadn’t worked since March. After First Texas foreclosed on his houses, he had helped to reorganize a friend’s business for $1500 a week (tax free, since Monesson has suffered losses sufficient to cover any income he’s likely to make for the next few years), and for the moment he was living off the savings.

“This is really badly done,” Monesson said. We were looking at a development featuring three-thousand-square-foot detached houses, each jammed gracelessly up against the next one. “I owned a lot here once, but when I saw what they were doing, I got rid of it. It looks like they never heard of landscaping.”

Monesson wants to get back into development, but he says he wants to operate on a smaller scale this time—an acknowledgment, perhaps, that he doesn’t have the right personality to manage a far-flung empire. He also says he’ll never again start out without capital, as he did the last time. Bankrupt debtors don’t get much attention from institutional lenders, so his only real hope is to find an investor, but the people spending the most money in Dallas these days are Canadians, and they prefer to operate through managers rather than partners. Monesson is insistent that he will not work for anyone but himself; he is, he says, too opinionated and individualistic to be a salaried employee.

He wheeled the car into a townhome development just south of LBJ. We were greeted by a phalanx of garages facing the street. “This is really plain vanilla,” Monesson said. “All the same materials and no alleys.” He shook his head, disgusted, and threw the car into reverse.

For the moment, he is pinning his hopes on winning an appeal of the property division in his divorce case. He wrote the brief himself. His share of the house where his wife and two children still live is probably worth $150,000, and he wants the court to order a sale and divide the proceeds. The money is exactly the amount he needs to start another restaurant venture, the nature of which he keeps to himself, except to say that it won’t be like Oz and there’s nothing like it in the Southwest. Monesson is optimistic, but, the merits of his case aside, divorce judges get overruled about as often as the U.S. Supreme Court.

We headed south along the tollway to look at the Highlands of Kessler Park. Even though he hadn’t built anything for two years, he seemed to know everything that was going on: who owned this lot, who built that project, what Roger Staubach just did. We passed a group of townhouses that towered over the roadway. “The first guy who bought this strip went broke,” Monesson said, “and the second isn’t doing well either.”

Very little remains from the glory days. Oz is gone, converted into the real estate office Monesson once intended it to be. His tract on Preston Road has been developed by somebody else. The combination of his bankruptcy and his divorce has driven away most of his friends. He neither had nor wanted many friends in the building industry, and because of his disparaging attitude toward his competitors, his rivals were (and are) delighted by his fall, though they acknowledge his talent. The cocktail party invitations and the civic attention ceased even before the bankruptcy, “like a hand turning off a tap,” Monesson says.

The money is gone, too. Monesson has hit up old acquaintances for money, something no one with immense pride would do if there were any alternative. All that is left are some odd pieces of furniture from Oz and his taste for the good life. He still travels frequently—his girlfriend is now a stewardess and gets breaks on plane tickets and hotel accommodations. And he still loves wine, although his own prized collection is in his wife’s home awaiting sale, and he has had to learn to appreciate California Chardonnay instead of French Bordeaux.

The tour ended at ChimneyHill, and Monesson drove in alongside another development. “They look just like apartments,” he said, delivering the ultimate insult. He pointed out some of the features at ChimneyHill that he considers earmarks of quality: roof-mounted air conditioners, alleys, green space, hillocks to break the flat terrain—and it was easy to imagine Monesson standing here when there was only maize, pacing off the lots and seeing the project take shape in his mind. Had he really failed? Are men judged by their monuments or their money? How are we supposed to keep score? We passed the clubhouse where the irate homeowners had once assembled to denounce the man I was riding with. The lawn looked green and immaculate in the late afternoon sun. “I really believe,” said Ron Monesson, “that I am the best at what I do.”

- More About:

- Business

- TM Classics

- Longreads

- Dallas