EVERYONE’S STILL TRYING TO FIGURE OUT what the white horse means,” Craig Miller explains. We are sitting in his makeshift office in Arlington: a gray, wall-to-wall carpeted, nearly windowless room filled with Maxfield Parrish art books, dog-eared X-Men comics, and pop culture ephemera—a self-made oasis in the midst of the interchangeable prefab homes of the Mid-Cities. This is where Miller, 39, and John Thorne, 35, produce Wrapped in Plastic, a bimonthly fanzine about director David Lynch’s short-lived television series Twin Peaks, and where we sit watching a pivotal scene in episode fifteen. The central mystery of the series—Who killed homecoming queen Laura Palmer?—has just been solved, and a white horse momentarily flickers across the television screen before fading away. “Everyone wants us to ask Lynch about the white horse,” says Miller, who has unruly red hair and on this day is wearing (what else?) a Twin Peaks T-shirt. “It’s kind of nonsensical, unanswerable. But new readers send us letters saying, ‘Please explain the white horse to me. I’m dying to know.’”

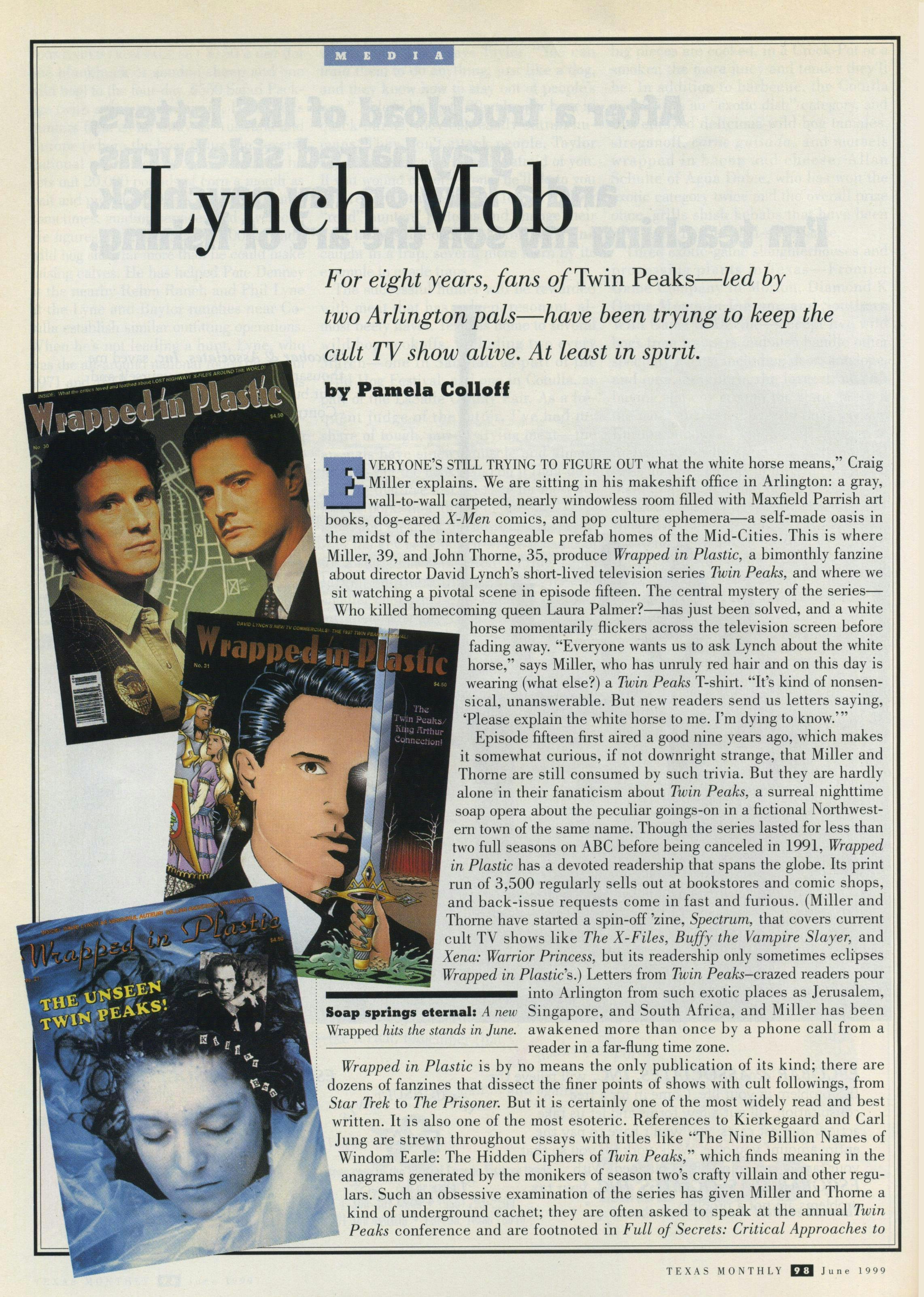

Episode fifteen first aired a good nine years ago, which makes it somewhat curious, if not downright strange, that Miller and Thorne are still consumed by such trivia. But they are hardly alone in their fanaticism about Twin Peaks, a surreal nighttime soap opera about the peculiar goings-on in a fictional Northwestern town of the same name. Though the series lasted for less than two full seasons on ABC before being canceled in 1991, Wrapped in Plastic has a devoted readership that spans the globe. Its print run of 3,500 regularly sells out at bookstores and comic shops, and back-issue requests come in fast and furious. (Miller and Thorne have started a spin-off ’zine, Spectrum, that covers current cult TV shows like The X-Files, Buffy the Vampire Slayer, and Xena: Warrior Princess, but its readership only sometimes eclipses Wrapped in Plastic’s.) Letters from Twin Peaks—crazed readers pour into Arlington from such exotic places as Jerusalem, Singapore, and South Africa, and Miller has been awakened more than once by a phone call from a reader in a far-flung time zone.

Wrapped in Plastic is by no means the only publication of its kind; there are dozens of fanzines that dissect the finer points of shows with cult followings, from Star Trek to The Prisoner. But it is certainly one of the most widely read and best written. It is also one of the most esoteric. References to Kierkegaard and Carl Jung are strewn throughout essays with titles like “The Nine Billion Names of Windom Earle: The Hidden Ciphers of Twin Peaks,” which finds meaning in the anagrams generated by the monikers of season two’s crafty villain and other regulars. Such an obsessive examination of the series has given Miller and Thorne a kind of underground cachet; they are often asked to speak at the annual Twin Peaks conference and are footnoted in Full of Secrets: Critical Approaches to Twin Peaks (Wayne State University Press) alongside the likes of Umberto Eco and Sigmund Freud. Despite such recognition, though, they have no illusions that their venture might someday turn a profit, or that they might achieve some measure of mainstream fame. This is a labor of love, in which cheap paper stock and obscurity are accepted facts of life. The reward is one that only die-hard fans could savor: The assurances that others out there share the same preoccupation.

Why does anyone still care about a show whose high point was a fifteen-minute dream sequence that featured a dancing lounge-lizard dwarf who spoke backward? For Miller and Thorne, at least, Twin Peaks broadened the possibilities of what television could be. “Twin Peaks is not a failed television experiment in weirdness,” they wrote in an early issue of Wrapped in Plastic. “It is a successful example of the incredible quality that is possible—though rarely accomplished—in the ridiculed medium of television.” Indeed, with its film noir—style visuals, complex plot lines, dozens of well-developed characters, quirky dialogue, and mesmerizing original score (by the great Angelo Badalamenti), Twin Peaks was brilliant and wholly original. But the series, which garnered comparisons to the films of Jean Cocteau and Luis Bunuel, was always a bit too avant-garde for prime time and seemed doomed for cancellation from the very beginning. Not that Miller and Thorne are willing to put it behind them. “Twin Peaks was challenging and different, and its ambiguity made it so distinct,” says Thorne, a former technical writer for Texas Instruments who has short brown hair and wire-rimmed glasses. “It wasn’t spoon-fed entertainment. Now people can’t get enough of shows like When Pets Go Bad.”

The idea for Wrapped in Plastic was hatched by Miller and Thorne at the Dallas Fantasy Fair in 1991. ABC had just canceled Twin Peaks,which had been logging miserable ratings in its Saturday night time slot, and both men were upset. Thorne was speaking on a Twin Peaks panel, for which he had plotted a meticulous chart of the characters’ relationships as well as a calendar of everything that had ever happened on the series. “I knew that Laura Palmer died on Friday, February 24, 1989,” Thorne says, “and that every episode took place on a day following her murder”—the second episode the next day, the third the day after that, and so on. “They never say it’s Saturday in the second episode, but the kids aren’t in school. And they never say it’s Sunday in the third episode, but they’re in church. The internal consistency!” Alas, the consistency finally gave out. “Late in the second season,” he continues, “the calendar was slightly off. The Miss Twin Peaks Contest should have fallen on Easter Sunday.”

When Thorne presented these and other findings at the Fantasy Fair, Miller sat in the audience rapt. He was impressed that someone else had such a thorough knowledge of the show. Afterward he approached Thorne and asked whether he would be interested in collaborating on a Twin Peaks fanzine, and Thorne said yes. It proved to be a good partnership. As a cartoonist who had majored in art at the University of Texas at Arlington, Miller had an eye for design, and he had learned the rudimentary skills of desktop publishing while putting out catalogs for his then-employer, Lone Star Comics. Thorne brought his own particular fetish for details to the table along with an academic sensibility; he holds a master’s degree in television production from Southern Methodist University, in Dallas, where he wrote his thesis on narrative theory in the TV series Homicide.

Not long after they joined forces, they settled on the name Wrapped in Plastic, a reference to Twin Peaks’ most enduring image: the lifeless, blue-lipped body of Laura Palmer, which was found bundled in a tarp by the side of a lake. (“She’s dead,” announces a fisherman who stumbles across her body in the first episode. “Wrapped in plastic.”) The debut issue—24 pages, with a simple design—was priced at $2.95, and it arrived in comic shops in October 1992. It began with the exhortation: “Think of it as a nationwide living room where we’re all hanging out talking about the television series.” Though it bore the noncommittal “published occasionally” on its cover, orders from distributors and letters from readers quickly convinced Miller and Thorne that they had hit upon something. “At the time,” Miller says, “we weren’t sure we’d get past issue two or three, much less forty.”

What they had hit upon was a thriving Twin Peaks subculture, whose denizens still flock every August to Snoqualmie, Washington—where the series was shot—for three days of cherry pie eating, coffee drinking, and schmoozing with actors who once played such peripheral characters as the Log Lady and the One-Armed Man. Of course, such obsessiveness was in vogue when the series was still on the air: A Los Angeles supermarket sold out of cherry pies on the day that the second season’s premiere aired; the Gray Line regularly ran Twin Peaks bus tours out of Seattle; and the New York Times reported that on Halloween 1990, “a thousand Audrey Hornes sashayed in pleated plaid skirts, tight sweaters, and saddle shoes, as multiple Agent Coopers, hair plastered down with Stiff Stuff, gripped their coffee mugs and deadpanned in Peak-speak” (Audrey was a femme fatale who was a schoolmate of Laura Palmer’s; Cooper was the FBI man who investigated her death and came to appreciate the town’s “damn fine coffee”). But even Miller and Thorne have been surprised by the extent to which the subculture is still intact years later.

In response, they have published ever-more-exhaustive examinations of the series—from essays such as “Moving Through Time: The Twin Peaks Cycle,” about the circular imagery in the show (“Even the doughnuts so beloved to Agent Cooper . . . can be seen as parodic rings”), to an episode guide for Invitation to Love, the soap that Twin Peaks characters watch religiously. There are also updates on the current projects of Twin Peaks actors (among them, the then-unknown David Duchovny) and spirited discussions of Lynch’s work (“David Lynch as Vengeful Auteur”). But Miller and Thorne draw the line at interviewing the show’s creator. “David Lynch’s nightmare, his image of hell, is probably being trapped in a room with Twin Peaks fanatics,” Miller emphasizes. “We’re not going to get into the minutiae of plot details with him. We’re not going to ask him, ‘What does the white horse mean?’ Besides, if we interviewed Lynch, what would we do next?”

What Lynch is doing next, however, greatly excites Twin Peaks fans—even if they’re not getting exactly what they want. “Ever since they brought Star Trek back, there’s been hope that Twin Peaks might get a second chance too,” says Thorne. “But it’s extreme fan naiveté. It’s not going to come back. It’s a pipe dream.” Still, Lynch himself is expected to return to prime-time TV this fall with Mulholland Drive, a two-hour pilot for a drama set in Los Angeles and starring, among others, Academy award—nominated tough guy Robert Forster, stage actress Ann Miller, and achy-breaky country singer Billy Ray Cyrus as a pool boy with bedroom eyes. Though little else is known about the series, ABC has described it as “vintage David Lynch, very much reminiscent of Twin Peaks.”

Understandably, Miller and Thorne can’t wait for the series to air, though they will continue to write about the one that first intrigued them nearly a decade ago. The forty-first issue of Wrapped in Plastic, which is currently in production, will feature a comparison of Lynch to another director, Peter Weir. “We’ll stop publishing the magazine when we run out of ideas,” says Miller. “We’ll give it up when we’re reduced to publishing the kinds of stories that the Star Trek ’zines were publishing before the sequel series came out—feature stories like ‘I Took Out Gene Roddenberry’s Trash.’”

Thorne nods in agreement. “Our friends’ reactions are, ‘You’re still doing that? What could you possibly have left to say?’” he says. “To them, it’s just a television show.”