Even as my heart was breaking, I had to acknowledge the magnificent irony of the room where Phyllis lay dying: the Willie Nelson suite. That’s what I called Room 11 at Christopher House, the beautiful, serene care center operated by Hospice Austin. Plaques outside the front door and the door leading to the small private patio explain that the room was adopted by Willie when he played a benefit for Christopher House at the Austin Music Hall in December 1994. Phyllis was in severe pain and heavily medicated, but I was told she could hear me. I bent down, kissed her cheek, and whispered, “Angel, you’re not going to believe this, but we landed in the Willie Nelson suite. Isn’t that neat?” If she heard me, and I believe she did, a smile stirred in her heart one last time.

Willie had been hovering over Phyllis and me like a guardian angel ever since our fateful meeting outside the press room of his Fourth of July Picnic in 1976. That’s when we began falling in love. We had known each other slightly since a chance introduction at the Cowboy Club tent outside the Cotton Bowl in the early sixties, but one or both of us had always been married. Her second husband was a Dallas jazz musician, and at the time I was married to my first wife, Barbara, and working as a sportswriter at the Dallas Morning News. I ran into her again in 1970 while on assignment for Esquire. She was divorced, working as an assistant to a photographer friend, Shel Hershorn, who was based in Dallas and was helping me on the story. Though I had remarried, we flirted a little, knowing it would go nowhere.

After that, I lost track of her until the picnic in ’76. Freshly divorced for a second time, I had moved back to Austin from New York to take custody of my ten-year-old, Shea. Phyllis had divorced her third husband and was living at Point Venture, on Lake Travis, with her eleven-year-old, Michael. (A second son, Robbie, lived with his grandmother in Grand Prairie.) We saw each other a lot that week, and by the end of the summer, we had set up house together. On the morning of October 20 we took out a marriage license, good for thirty days. Late that night, as we were drinking at the Texas Chili Parlor, near Fifteenth and Lavaca, our friend Doatsy Shrake pestered us to tie the knot then and there. I remember thinking, “Why the hell not?” As it happened, Doatsy’s husband at the time, Bud Shrake, had purchased a certificate for $50 from the Universal Life Church that authorized him, as “doctor of metaphysics,” to perform weddings and such. Our chapel was the Chili Parlor’s back room. The Right Reverend Bud quickly scribbled the words of the marriage ceremony on a cocktail napkin, while Doatsy drove out to Rollingwood to gather up our kids and bring back a bouquet of Texas wildflowers.

Vows repeated and multiple tequila toasts made, the movable feast ended at the Bull Creek Party Barn, where Willie and his band were playing. Willie and I were casual friends by then. Without hesitation I pushed my way to the front of the room and asked him if I could join the band and sing a song for my new bride. He agreed instantly, pulling me onstage. He handed me a spare guitar, which of course I couldn’t play, not that that was the slightest obstacle to a scheme that had taken on a life of its own. Instructing the band to play in C, the only key I could think of, I moved to the microphone and waved to the audience, who had no idea what the hell was happening. Guided by one of those spiritual muses that Willie tells me float around us like invisible fireflies, I began to compose and sing a song. My pet name for Phyllis was Main Squeeze, and the song was “Main Squeeze Blues.” Though the words, alas, are lost—and have been since they escaped my lips—the audience seemed to enjoy them. I’m still amazed how easy all this came about, and how gracious Willie was. It was a magic night.

So that was our start, Phyllis and me. Neither of us had the slightest notion where we were headed. Our combined marital track record had hardly inspired confidence, and yet after three decades together, we were more in love than ever, the envy of friends, married or single. At Phyllis’s memorial service, on June 30, our friend Bill Broyles told the mourners that he was reminded of that line in When Harry Met Sally, after Meg Ryan simulates an orgasm in the middle of a crowded diner. As her last moan dies down, the old woman at the next table turns to the waitress and says, “I’ll have what she’s having.” That’s how Bill felt when he looked at us, he said: “Could any two people have had so much fun, shared so much heartache, lived so fully, loved so much?”

Ecstatically happy, we were going to celebrate our thirtieth anniversary on a trip to Istanbul with our great friends Jan Reid and Dorothy Browne. But our plans came crashing down in March when we learned that Phyllis had cancer. Two months later I was told that it was terminal. A month after that she died.

When I first heard that word, “terminal,” I thought, “This can’t be happening.” Not to us. Not to Phyllis. She had always been so strong, so vital, so unstoppable. She was my anchor, my soul mate, the love of my life. It couldn’t end like this. We know that life is temporary, a gift we’re not meant to understand, but death is much more complex, a poorly defined state for which there is no preparation and to which God is a bystander. At 71, I’d struggled with heart disease for nearly twenty years; she was six years my junior and had never been hospitalized or, as far as I remember, even had a bad cold. We had talked about death, of course, but we assumed that I would be the first to go. I was ready, but so was she. I had told her many times, and she had told me, “If I drop dead tomorrow, my angel, my life has been so great, so wonderful, so full and complete that I can ask for nothing more.” And I can’t. But I can’t believe she’s dead either.

Our first hint of her mortality came in early March, when she was unexpectedly short of breath during a tour of a house with some realtor colleagues from her company, AvenueOne Properties. A day or two later, she complained of a sharp pain in her chest. On March 15, on the advice of her personal physician, Belle Hoverman, I took her to the emergency room at Seton Medical Center. A CAT scan revealed a mass in the left side of her chest, a tumor that was pressing against the veins of the heart and causing the pain and shortness of breath. “It’s cancer,” Belle told us bluntly.

I was stunned. Phyllis began to cry. She was a crier by nature; crying was her safety valve, her way of dealing with extremes of emotion. She burst into tears during sad movies or while reading gripping novels or when someone did something nice and unexpected—for example, when I brought her a bouquet of lavender tulips that time in Paris—or even, on occasion, over something as inelegant as my remembering to pick up my towel after showering. Doing nice things for people was second nature to Phyllis, but when someone did something for her, it touched that deep well where her tears were stored. This was different. These were dark, smoldering tears that came in hot bolts. She was terrified. We both were. Nothing in our lives would ever be the same—that much I knew.

The diagnosis was “a poorly differentiated tumor of unknown primary,” which means that the primary source is unknown and may never be known. It also means, I know now, that a cure is unlikely. Belle’s husband, Russell Hoverman, is an oncologist at Texas Oncology Cancer Center in Austin. Belle picked another doctor from his group, John Sandbach, to be in charge of Phyllis’s treatment. Although a mammogram the previous November had revealed no problems, Sandbach thought he felt some lumps in her left breast and ordered a biopsy. There were several small tumors. A few days later, Phyllis had her first round of chemotherapy, a process that took about three hours and seemed surprisingly easy. That night we joined friends at a book signing and cocktail party for our friend Stephen Harrigan. Phyllis was her usual self: beautiful, warm, sexy, funny, an alluring and spontaneous presence who lit up the room.

A nurse had warned that after her second chemo treatment, scheduled in three weeks, her hair would begin falling out. Predictably, Phyllis took matters into her own hands and had her regular hairstylist give her an attractive buzz cut. With her best friend, Doatsy, in tow, she went shopping for wigs. Help poured in from all corners. Our next-door neighbor Ken Shine, who is the executive vice chancellor for health affairs for the University of Texas System, called the staff at M. D. Anderson, the university’s famed cancer center in Houston, and arranged for us to get a second opinion. For the moment, we felt good about the future.

But the pain in her chest got progressively worse. Realizing that the tumor was particularly aggressive and spreading fast, Sandbach decided not to wait for a second round of chemo and started her immediately on a full-bore course of radiation treatments—five days a week for six weeks. The radiation beam trained on the tumor in her chest, proved far worse than the chemo: It blistered her throat and esophagus until she could barely swallow. I assigned myself the task of measuring out her medications, which included not only la-la land doses (Sandbach’s term) of morphine and codeine but also pills for anxiety, nausea, depression, and constipation (constipation is a common side effect of large amounts of narcotics). A radiation specialist prescribed a local anesthetic solution called a triple mix—a combination of lidocaine, Tylenol, and Maalox—which, when gargled and swallowed, numbed her throat and permitted her to eat small servings of soft food. Even so, eating or sipping water was almost more than she could bear; dehydration was a serious concern. And no matter how many laxatives she took, constipation was a constant problem. As the drugs accumulated in her body, the pain began to subside, but the constipation only got worse.

On the way to M. D. Anderson with Doatsy in early May, Phyllis got it in her head that she no longer needed the pain meds, that once she stopped taking them, the constipation would take care of itself. By this time she had been on large doses of narcotics for nearly a month and, without realizing it, was addicted. The next day she went into severe narcotics withdrawal and had to be rushed to the emergency room. And then came the second opinion: A breast cancer specialist determined that the primary cancer was not in the breast, as Sandbach had believed, but in her lungs. Whatever this portended, I knew it wasn’t good.

Four days after returning from Houston, Phyllis was back at Seton, suffering from severe dehydration and malnutrition, and the staff was pumping her full of fluids and nutrients. They were also trying to adjust her meds so she would be both alert and pain free, something that was proving increasingly difficult. Phyllis pretended it was business as usual. She kept her cell phone on her bedside table and answered every call herself. Doatsy and I still laugh about the afternoon when, awakened from a deep, drug-induced sleep by the ring of her cell, she bolted upright, went into her husky businesswoman register, and began rattling off prices and square footage from memory. Another time I heard her promise to meet a client at a Town Lake town house that afternoon at three. She couldn’t make it to the bathroom without help, and now she was promising to meet a client; the narcotics were doing the talking. “Phyllis Ann,” I said in my scolding voice, “doing business is not a good idea just now.” She looked hurt. Tears welled in her eyes. It hadn’t occurred to her that something as trivial as cancer could get in the way of work.

Real estate had been a huge part of her life, and she was very good at it. “Realtor to the stars,” one journalist had labeled her. Her clients had included the actors Dennis Hopper and Diane Ladd, as well as numerous well-known writers, artists, and musicians. With no apparent effort she became friends for life with nearly every person she worked with or found or sold a house for—or just met for a drink and a laugh. She adopted people on sight. In short order she knew the names of their children and grandchildren and pets and was ringing their doorbell with gifts of toys, children’s clothing, or Milk-Bones. People knew that she would be there for them.

Phyllis’s mom, the unsinkable Lucy Mae McCallie, had arrived from her home in Wetumka, Oklahoma, and the two of us camped by her bedside from early morning until late at night. Doatsy, Dorothy Browne, and Michelle Keahey, a young realtor whom Phyllis had taken under her wing and had come to love like a younger sister, became part of our core group of caregivers. Michelle showed up in Phyllis’s room one day with an enormous stuffed dog, nearly as big as our male Airedale terrier, Willie. Phyllis named him Rufus and slept cuddled against him.

I sensed that the cancer was spreading. What appeared to be a small tumor had started to swell beneath her naked scalp. The wigs she had selected were too hot and uncomfortable, so she switched to a series of scarves and headdresses. A mysterious pain afflicted one of her knees, and, on top of everything else, a racking cough developed into pneumonia. Phyllis had already lost at least twenty pounds. Her skin sagged and her muscle mass flattened; she was virtually skin and bone, a sad relic of the stunning and curvaceous high-kicker who’d once twirled flaming batons for the Wetumka High band. I remember watching her sleep one afternoon, relieved on the one hand that she was resting peacefully but aware, too, that she was literally vanishing before my eyes.

It got worse. Toward the end of her twelve-day hospital stay, doctors ran a fiber-optic bronchoscope into her bronchial tubes and took photographs. The pictures made Doatsy and me cringe: In brilliant color, they showed splotches of blood covering one quadrant of her lungs and masses of ugly white cancer cells clumped along the base. We tried to keep them from Phyllis, but she insisted on looking for herself. The sight was too much: She had a full meltdown and needed to be sedated.

On a routine visit to Belle Hoverman’s office a day before she was supposed to go home, I learned the terrible truth: Her cancer was not curable. The cancer cells were spreading essentially unchecked, and the chemo and radiation were only making her sicker. The battle was hopeless. It was time to face up to the inevitable: She would be dead in a few months. Belle mentioned hospice care and the importance of keeping her as comfortable as possible. I thanked her and walked out to the parking lot, shaking all over.

This was the worst day of my life, or so I thought; worse days were to follow. I drove around town for a long while, thinking, praying, wondering why this had to be. Later that day, I broke the news to Doatsy and Dorothy and a few close friends. In the meantime, the staff at Seton had given Phyllis a blood transfusion, and when I walked into her room, I could hardly believe the change in her. She was sitting up, laughing and jabbering on her cell phone. She blew me a kiss and gave me one of those smiles that always buckled my knees. I knew I had to tell her the truth, but not just yet. She was due to be discharged the next day, a Saturday, and Doatsy and I decided to wait until at least Sunday night to tell her the news. Let her enjoy a day at home with her family and our beloved Airedales.

She didn’t break down the night we told her, as I had feared. Tears filled her eyes, but she looked away to another part of our bedroom and said in a dry voice, “So it wasn’t just my imagination.” She knew. But in a strange way, hearing the bad news from me somehow made it easier. Belle had told me that victims of terminal diseases often feel a sense of relief when they hear the truth. I felt relief too. For five terrible weeks I had struggled with great frustration, desperate to do something for her but never knowing exactly what. Now I knew: Help her with the end. Care for her. Make her comfortable. Protect her from pain.

Doatsy went with us to Sandbach’s office the next morning. We had already decided that additional chemo and radiation would only prolong her agony. Sandbach agreed. He was a founder of Hospice Austin, which offered a wide range of home medical and nursing care and emotional support. If we wanted him to, he would arrange everything. “How long?” Phyllis asked him. At the outside, he said softly, six months. On the way home, she told me, “I don’t want to wait six months.”

Phyllis and I knew from the moment we started our lives together that we would live it to the max. Our view was, anything worth doing is worth overdoing. If we had extra money, we dismissed the practical option of a savings account and spent it on something fun, like travel. In the late seventies, just after I had signed a book contract and sold a previous book in paperback for six figures, we put the kids in boarding school and moved to Taos, New Mexico (it is not true, as I sometimes joked, that we left the boys no forwarding address). We had planned to be there a couple of months but stayed a year and a half, hiking the trails of Carson National Forest with our Airedales—we had one, two, and sometimes three of the breed most of our married life—and exploring New Mexico and Colorado. I took work trips to El Paso to research the book I was writing on the dope-dealing Chagra brothers and the murder-for-hire of federal judge John Wood, but mostly we just had fun and savored each other’s company.

When we came home to Austin in January 1982, broke but happy, I joined the staff of Texas Monthly and Phyllis started her highly successful career in real estate. Over the next twentysomething years she worked with a procession of companies: Eden Box and Company, West End Properties, and finally AvenueOne, where she served on the board. She was also on the board of the Austin Public Library Foundation, which gave her enormous satisfaction (and gave the foundation someone who could organize, create, and outwork a dozen her size). Almost every year—usually in the fall, when we celebrated our anniversary and her birthday—we took fantastic trips: to New York to hear our favorite opera, La Bohème; to Boston and Martha’s Vineyard; to San Francisco to celebrate my fiftieth birthday; to Chicago for a rendezvous with Phyllis’s old friend Sherry “Bad Bunny” Broder; to Mexico and Canada and especially to Europe. Taped inside the door of Phyllis’ small home office is a list of our ten European trips, dating back to a tour of Germany, Paris, and London in October 1987. Our final trip was last November, just after Phyllis’ sixty-fifth birthday, when we went with Doatsy and other friends to Paris and Amsterdam. With each trip we fell more passionately in love and grew more attuned to and appreciative of the rare gift that God had given us.

In the late eighties, Willie Nelson helped Bud and me sell an old screenplay to CBS. Phyllis and I used our share of the money to buy a lot in the Judges’ Hill neighborhood of Austin, just west of downtown, and to build our home, which Phyllis designed and decorated with her unmistakable eclectic style. A year later CBS filmed a sequel, and this time we spent the money on finishing out our patio and landscaping the yard.

When you’ve lived life to the max, dying seems especially slow and clumsy and mean. I prayed a lot during those months, prayed for a miracle I knew God wasn’t disposed to honor. I funneled a lot of my bitterness and rage in God’s direction. Watching her suffer was the hardest thing I’ve ever done, but it would have been infinitely harder without the angels of Hospice Austin.

Starting in late April, a team of professionals came to our home, headed up by our assigned nurse, Barbara Winchell. Barbara or one of the staff nurses was available 24 hours a day. “Our job is to keep her alert and as free from pain as possible,” Barbara told me, and that’s what she did. She had directed the hospice staff to stock our bedroom with oxygen equipment, a hospital bed with adjustable rails, a wheelchair, and a walker. Anything Phyllis asked for Barbara found. She visited us weekly, or more often if we needed her, making certain that Phyllis was comfortable, that our family was okay, and that we had an abundant supply of all the meds we needed. My instinct was to overmedicate, but Barbara made sure I knew when and how to use each medication in our kit. The most important thing she did was listen to Phyllis and talk to her, letting all of us know that we were not alone in this. Knowing what to expect in a normal dying process helps alleviate some of the fear; we came to understand that these final weeks were a celebration of what Phyllis’s entire life had meant.

I had gotten a glimpse of the hospice experience when my mom died some years ago, but this was the first time I understood what hospices are really about: They’re about helping families deal with death. Patients who have an incurable disease and six months or less to live are eligible for hospice home care, which is usually paid for by private insurance or Medicare. Ability to pay is not a consideration at Hospice Austin, one of only two nonprofit hospices in Central Texas. The hospice depends on donations from individuals, corporations, and foundations, as well as a group of about four hundred volunteers who augment the two hundred on the professional staff. Each patient is assigned a team of caregivers that includes a registered nurse, a nurse’s aide, a social worker, a chaplain, and a volunteer.

Over the years Phyllis’s boundless generosity and infectious good humor had helped or supported or made life easier for countless people, and now they overwhelmed us with love and best wishes and offers of help. Dozens of cards and letters arrived daily. Phyllis read every one, some of them several times, and made meticulous lists of people she needed to write and thank. One letter in particular caught my eye: Phyllis read it eight or ten times, crying her way through every reading. It was from a former Austin hospice nurse whom Phyllis had befriended several years earlier. Her name is Lorri Hatfield, and she lives in North Carolina now, but three or four years ago Phyllis sold Lorri and her husband a home near Austin. As I discovered later, Lorri suffers from bipolar disorder, that manic-depressive netherworld where all things are dark and fearsome and where sufferers are forever alone. A year or two after the home purchase, Lorri was hospitalized, divorced, and friendless. Phyllis, of course, adopted her on the spot. I didn’t understand the significance of their friendship or its depth until I read the letter.

It said, in part: “When my life was hanging by a thread, my illness raging, you never once passed judgment or met me with anything but genuine compassion and respect. You listened to me through the darkness and the light … loved me when I could not love myself … [gave] me courage and support in the midst of so much uncertainty … Thank you for every visit to the hospital, every cup of coffee, every letter and phone call … every smile and laugh that we shared, every hug. Thank you for believing in me …”

As Phyllis’s disease took control, there were mostly bad days, but there were some good days too. One of the best was a Saturday when Michelle and her colleagues from AvenueOne showed up at our house with a pickup load of plants, dirt, paving stones, and crushed granite. Phyllis took great pleasure in a semiannual ritual in which she redid the landscape of our backyard, but her illness made the chore impossible now. Michelle and the others came to do it for her. Over the next twelve hours they transformed patches of weeds and hard-packed dirt into a magical open space of flowers, leafy things, casual boulders, stone pathways, and terraced beds—a job that would have cost thousands of dollars if professionals had done it. It was a gift of astonishing generosity and love.

When there is a medical crisis that can’t be handled with home care, Hospice Austin sends patients to Christopher House. Phyllis went to Christopher House two times but came home only once. The first was June 5, following a frightening period in which she had hardly touched her food, slept eighteen or twenty hours a day, and was often incoherent. I thought that was the end, but Barbara realized that the problem was simply my heavy hand with the medication. Barbara called and arranged for Phyllis to be admitted to Christopher House. We were assigned to Room 8, just down the hall from the Willie Nelson suite.

More like a resort than a hospital, Christopher House is peacefully tucked away on a wooded lot in East Austin, in a one-story building surrounded by shaded pathways and a lush garden with chirping birds, a gazebo, and a bubbling fountain. Fifteen large, private rooms are spread along a hallway, each equipped with a TV, VCR, refrigerator, microwave, lounge chair, and couch that folds out into a bed. That’s where I slept the next two nights. The rooms seem open and friendly, partly because each has a rear entrance too, a door leading to a small patio and on out to the garden. This is a handy arrangement when families bring pets for a visit, which the hospice not only allows but encourages. “Pets are part of the family, part of the therapy,” explained Lorraine Maslin, a nurse with a thick Scottish accent and a strong, almost saintly demeanor.

Watching Lorraine and the staff over the next two days, the smooth and seemingly tireless way they attended to the physical and emotional needs of not just the patients but their families, I realized that hospice doctors and nurses are a different breed, one that is not easily understood or explained. Theirs is a labor of love that redefines heroism, a job that goes mostly unseen except by their colleagues and those they assist but one that carries its own special nobility. Day after day, week after week, they work with pain and suffering and death—always death—in a grim atmosphere of fear and hopelessness. And yet they seemed among the happiest group I’d ever seen. “This is a happy place where sad things happen,” Lorraine told me. It was apparent that the doctors and nurses were very supportive of one another. They held regular “de-stressing” sessions in which they talked about things that had been most difficult. “When the well runs dry, you have to be very resourceful,” says Mary Stephenson, a longtime friend who is the director of Hospice Austin’s volunteer services. “Each of us has her own way: family, religion, art, music, whatever works.”

One of the nurses gave us a small booklet titled “Gone From My Sight: The Dying Experience,” which explains what families can expect during the final weeks and hours. In the last month the body begins to slow down, preparing itself to die: Patients lose interest in food, and depression often overtakes them. I realized that Phyllis had passed through this stage and was about to move into what was called “the rally stage.” Terminal patients frequently rebound ten or twelve days before the end. Appetites suddenly return. They feel energized, alert, and alive. Then they crash and die. So it was that after two days of tender care from the Christopher House staff, and some adjustments to her meds, Phyllis was sitting up in bed, laughing and joking and telling me that what she really wanted right then was a big, fat hamburger, with extra mustard.

Those last two weeks, which we spent at home, are a blur. Somewhere in there she fell and fractured her ankle in two places. The days were long and often difficult, but for one brief interlude Phyllis seemed to be her old self again; though much weaker and less graceful, my peerless, unconquerable angel had returned. She read, sewed, wrote dozens of thank-you notes, and reorganized her files, all the while talking on the phone or visiting with old friends. She found chores to keep me occupied and out of trouble. One or two times each night, she woke in pain. I’d give her some morphine or triple mix, help her to the portable toilet, and then get her back to sleep again.

She woke up every morning just like she used to, at six-thirty. Half-asleep, I’d help her to her wheelchair and take her to the living room, dragging fifty yards of oxygen hose behind me. Lucy Mae would already have started making coffee. I’d return to the bedroom for her book and her sewing basket, and then Phyllis and her mom would spend the morning chatting and enjoying this last time together. In the evening, Phyllis and I would sit on the patio, drinking in the explosion of colors and textures of our newly refurbished backyard, listening to jazz, sipping wine, laughing at silly things the dogs did. One evening Doatsy brought her dog Sophie over and we celebrated Willie’s second birthday. Another evening, to my distress, Phyllis produced her trusty BB gun and began taking potshots at a marauding squirrel that had overturned a potted plant. However infirm, she was in her element; things were good.

There were times every day when she would despair and collapse into tears. I would hold her close and rub her shoulders, knowing that there were no words to describe what she was going through. One day she sobbed: “I just want this to be over.” So did I. So did everyone who loved her. I knew by now that a miracle wasn’t coming. I talked to God, but he never talked back. I began to wonder: Does he care? Is this just another tiny episode in his opus magnum? Are we too small to see? Is he too busy being God to worry about us poor mortals?

Her final 24 hours were pure hell, softened and made manageable by the soothing confines and unbelievably compassionate staff of Christopher House. The last chapter had caught me by surprise. It was Friday, June 23, and we had spent a pleasant evening on the patio. Phyllis seemed tired but otherwise comfortable when I put her to bed. But she woke up at about three-thirty Saturday morning, pain tearing at her left breast and side. It was far and away the worst pain yet. I gave her triple mix, then morphine, then more morphine, then some codeine. The drugs weren’t working. “I don’t know what to do,” I confessed. Phyllis cried out, “Wake my momma.” So I woke Lucy Mae and together we tried to comfort her, but she was crying and calling out, over and over, “Oh, God, please stop this pain. Please, God, stop it.” I telephoned the hospice, which sent out a nurse, who quickly assessed the situation and called for an ambulance to take her to Christopher House.

Lorraine met us at the door of the Willie Nelson suite and took charge. “It’s going to be okay,” she assured us. She kissed Phyllis, hugged me, and got busy. The doctor on duty that morning was Sarah Legett, a marvelous palliative care physician. She ordered a morphine drip and a battery of other painkillers and tranquilizers. Sarah hugged me and led me out into the hallway. “We’re going to take care of her,” she told me. “We’ll keep increasing the level of drugs until she’s out of pain. Making her comfortable is our primary consideration.” I nodded in agreement. Death was no longer the enemy.

All day Saturday, our core friends and family arrived: Doatsy, Bud, Jan, Dorothy, Michelle, Lucy Mae. Late that night Phyllis’s brother, Jim McCallie, and his wife, Melinda, drove in from Oklahoma. Because of the drugs she’d been taking to manage the pain, Phyllis was deeply sedated. We took turns sitting beside her, holding her hand, talking to her, not really sure she could hear us. We talked among ourselves, laughing at things we’d done or said over the years. “Remember that time you guys were coming home from a late party and you stopped on a country road to pee and Phyllis woke up, not realizing you weren’t there, and drove off without you?” Hours crept by. We sent out for food. We played a Dave Brubeck album. We paced the pathway to the garden and back dozens of times and sometimes sat on a bench by the fountain, listening to the songbirds. Lorraine was right: This was a happy place where sad things happened.

The others left before midnight—all except me and Lucy Mae. I moved the heavy lounge chair next to the bed so that Lucy Mae could be close to Phyllis. She sat there the remainder of the night, sometimes dozing but always clutching her daughter’s hand. I unfolded the couch into a bed for myself, but I didn’t sleep much either. In the dark, we could hear Phyllis breathing. As the night wore on, her breathing got more labored and slowed, at times stopping completely for a few seconds before chugging on.

Around three that Sunday morning, the night nurse came to check on her. The nurse said something that I didn’t understand, but Lucy Mae and I both knew that the end was here. We positioned ourselves on either side of the bed, each stroking one of her hands. Her eyes were half-open, but I knew she didn’t see us. A small rattling sound escaped from her mouth, and an instant later I felt her spirit lift and float away. I kissed her and said, “Now you’re at peace, my angel.” Lucy Mae repeated, “Now she’s at peace.” In all those weeks that Phyllis was dying, that was the only time I saw Lucy Mae break down. She cried for a long time, me sitting with my arm around her. An hour later, when the crew from the funeral home had arrived to take her away, I went back to the Willie Nelson suite to say one last good-bye. I kissed her forehead and stood over the body, realizing that Phyllis wasn’t there anymore.

At her memorial, Bud spoke these lines: “In my life there are a few very special people that I refuse to let death have. Instead of thinking of them as what we call dead, I prefer to believe they have moved to France to some beautiful small town way up in the Alps where the phones don’t work very well and there’s no Internet. So that way I’ll be seeing them again somewhere down the road. Phyllis is one of those special people … She’s probably wearing ski boots by Chanel this afternoon in her chalet in the mountains in France. So I am saying, ‘Au revoir, Phyllis. I love you. I’ll see you in Paris in the spring.’”

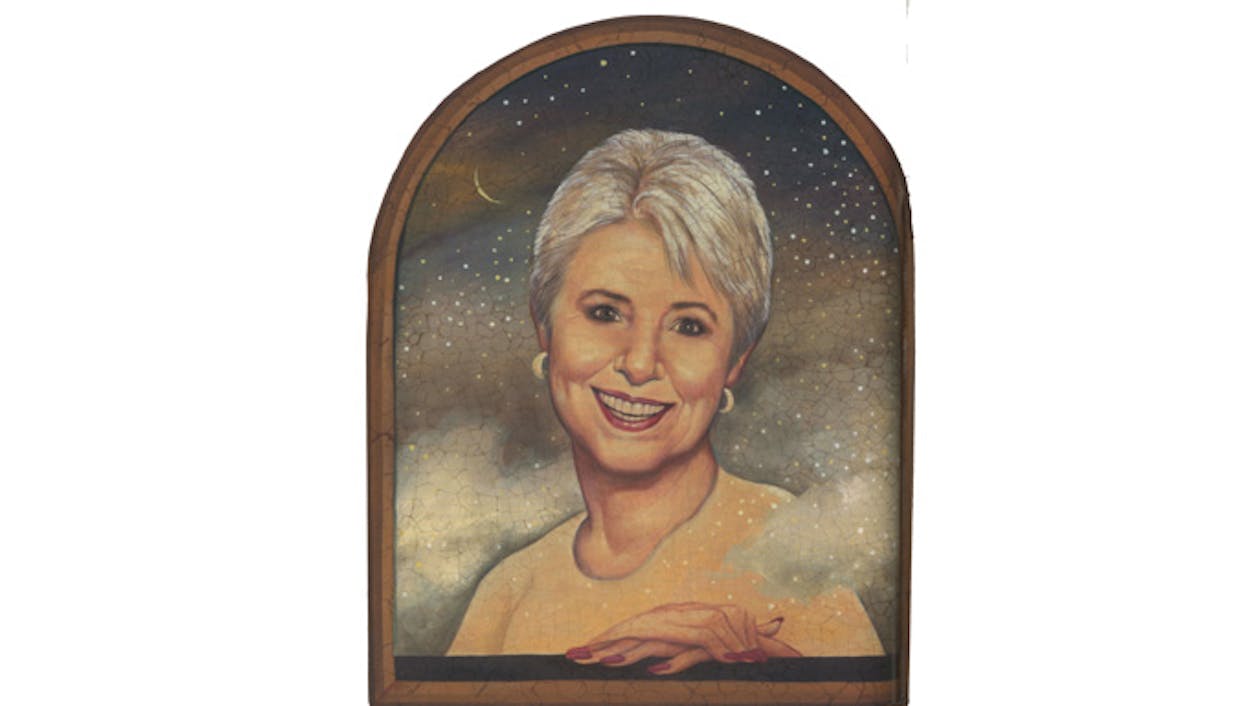

People ask me how I endure each day without her, how I can stand to live in that house with all those terrible memories. Well, I say, the house has been here for nearly eighteen years, and only recently has it been host to very bad things. Phyllis is everywhere I look. She’s there in her huge walk-in closet of stylish, in-your-face clothes, heavy on black, leopard, and zebra print, every rack coordinated, every shoe box carefully labeled. She’s puttering in her office, old photographs of me and her kids and our grandkids pasted to the wall, next to a priceless newspaper photo of Phyllis herself as a Wetumka high-kicker.

The carnival masks that we bought in Venice mock us from atop a bookshelf. The framed photograph of a 1909 Estonian street after an early morning rain, the one we discovered together in that gallery in Moscow, looks down from the wall above the mantel. That photo of Phyllis and Doatsy in front of Les Deux Magots last November in Paris (God, both of them are so beautiful). Every drawer and closet and crawl space has her fresh prints. Every painting, plant, lamp, and piece of furniture is where she willed it, in its perfect place. Every time I step inside our kitchen, a rhapsody of silence fills my heart and sings her name. When I turn out the lights at night, I hear her whisper. And, when sadness threatens to swallow me, I feel her kiss.

Sometimes I feel as if I’m coming apart. But then I catch myself and realize that our dogs are staging a vicious fight at my feet, hoping to amuse me. The dogs know. They give me funny glances, as though I’m hiding her somewhere in plain sight. I laugh and reassure them: “She’s here. Can’t you feel her?” And they begin to romp and frolic and tug on a section of knotted red cloth that she sewed for them. I don’t know if she’s in Paris or up there with God’s first rank of angels. I don’t care. I just hope she knows that I want to be there with her.