This story is from Texas Monthly’s archives. We have left the text as it was originally published to maintain a clear historical record. Read more here about our archive digitization project.

The end was as abrupt as the beginning and the middle had been interminable. At 7:11 p.m. on Tuesday, November 2, as the voters of Houston inched their way home on its rain-slick freeways, campaign worker Chuck King listened to the numbers coming over the phone from the Harris County clerk’s office downtown. He wrote them down. He hung up the phone. He turned to the mud-splattered, bedraggled group clustered around the tiny black-and-white portable TV on his desk and gave them the news. Andrews: 1816. Faubion: 1557. It took a moment for the truth to sink in; when it did, the little inner circle of Andrews’ faithful whooped and shouted, hugged one another and flung high fives. Vic Driscoll, the campaign manager, stood slightly apart, his eyes red-rimmed. His man, Mike Andrews, had won the absentee voting, and Democrats never carry the absentees. Now it was almost inconceivable that he could lose. Seventeen minutes later, at 7:28 p.m., Dr. Richard Murray, calling the election for KPRC-TV, declared that the congressman-elect from the newly created 25th District of Texas was indeed Democrat Michael A. Andrews.

The candidate, waiting at home with his family, knew nothing of that. The candidate was in the shower. As he dealt with the accumulated sweat and grime of twelve hours spent shaking hands at the polls, his wife, Ann, took the message from headquarters—including the news that a television camera crew was on its way to the house. The winner would be granted no interval in which to savor that he had at last seized the prize he had been pursuing so doggedly for almost four years. Incredibly, in half an hour, it was all over.

Ten miles away, in a not quite completed Hilton Inn near Hobby Airport, the sense of unreality was even greater. While his supporters nibbled miniature quiches and nursed drinks in the ballroom, Mike Faubion huddled with his wife in a room down the hall. Unlike Andrews, Faubion had seen Murray’s pronouncement, but he refused to believe that the race was over. He had proved the prognosticators wrong before.

He had sat in his living room one day in the summer of 1981 and seen a map of the new district in the newspaper, and an idea had begun to grow in his mind. He was the right man to represent the district. His house lay right in the middle of it. His law office was inside it. His wife, Tamara, had taught school in it. He was a Republican, and the district had voted for Ronald Reagan. He knew he could win. But the experts had never believed him. They’d said he didn’t have enough money to survive the Republican primary; he’d knocked on 10,000 doors and made the runoff. They’d said he couldn’t win the runoff; he’d won it. Mike Faubion hadn’t come this far just to concede on the basis of 3400 absentee votes. He and Tamara walked down to the ballroom to smile and slap backs and spread the word: we’re not giving up, they assured their people, it’s too early yet. So the newsmen, impatient for the catharsis of a concession speech, hunkered down to wait, and Mike and Tamara went back to their room, armored in their bright, blank smiles.

An hour or so later, greeting their own supporters at their own party, Mike and Ann Andrews wore smiles that were only a little less dazed. For on that night more still united these two men than separated them. They shared memories of the thousands of miles traveled crossing and recrossing the district, the anxious poring over of polls, the dawns at factory gates and the midnights plotting strategy. They shared the isolation, the uncertainty, the endless asking, asking, asking—for money, for time, for votes. But now, though neither could quite grasp it, everything had changed. One had won and the other had lost. One would sink back into obscurity, perhaps forever. The other would become one of the most visible, most powerful public men in one of the biggest, richest, most powerful cities in the world.

The Territory

The 300 square miles of real estate that dominated the imaginations of Mike Andrews, Mike Faubion, and some ten other candidates for more than a year is as uninspiring a chunk of coastal prairie as an indifferent Creator ever slapped down upon the face of the earth. It begins on the west at the point where U.S. Highway 90 crosses the line between Harris and Fort Bend counties, and from that undistinguished font rolls eastward across the southern quarter of Harris County, gathering bulk and character as it goes. Gradually the faceless apartment complexes and strip centers of Southwest Houston give way to the aging but respectable brick homes of Willowbend and Westbury, where the long-entrenched middle classes view the world with suspicion from behind thickets of burglar bars and vote Republican. Tucked in beside them is the Jewish enclave of Meyerland, which traditionally casts its ballots in the same direction. Skirting the cities of Bellaire and West University Place, District 25 sidles northward to encompass the blue-chip neighborhoods around Rice University. Then, leaping Main Street, it bursts upward into the imposing high-tech fortresses of the Texas Medical Center.

After meandering to the south. District 25 erupts briefly into the hurdy-gurdy commercialism of Astrodomain before slinking under the South Loop and sliding back into a state of nature. To the east it emerges onto a great swath of black neighborhoods, from middle-class Brentwood to downright poor Sunnyside, both solidly Democratic. It takes in Hobby Airport and the integrated lower-middle-to middle-class subdivisions nearby before crossing the Gulf Freeway into urban-cowboy land—the largely white, largely blue-collar municipalities of Pasadena, Deer Park, and La Porte, which forsook their Democratic ways in 1980 to vote for Ronald Reagan. Running down the coast, it scoops up the bedrock Republican stronghold of Clear Lake City, with its NASA scientists and engineers. Meanwhile, along the Ship Channel, the district’s northeastern border, masses the shoulder-to-shoulder phalanx of industrial plants that power Houston’s economy: Phillips Petroleum, Exxon, Georgia Pacific, Arco, Goodyear, Tenneco, Shell Chemical, Diamond Shamrock, Boise Cascade, Upjohn, Fluor, B. F. Goodrich.

Of the district’s inhabitants (some 524,107 souls by 1980’s enumeration), one quarter are black and 14 per cent are Hispanic (although those percentages drop to 20 and 5, respectively, if you count only the registered voters). The district was created by the Legislature in 1981 out of precincts that had previously been divided among one Democrat (Mickey Leland) and three Republicans (Bill Archer, Jack Fields, and Ron Paul). From 1976 to 1980 Republican congressional candidates fared increasingly well in those precincts—garnering 44.7 per cent of the vote in 1976, 47.6 per cent in 1978, and 48.4 per cent in 1980—and Reagan carried the area in the Republican landslide of 1980.

Most of the voters in the district call themselves conservative and most of them vote Democratic, but they are at least one step removed from the mainstream of Texas’ historic Democratic conservatism, with its deep rural roots. The district exists because a lot of people left the urban Northeast at the same time that a lot of people were coming to Texas. You might say it simply moved from New York City to Houston. But in the process it changed character. It left as an urban liberal and arrived as an urban conservative, and in that it is emblematic of a shift in American politics that is still under way.

The word most often applied to the district over the course of the campaign was “diverse,” but that doesn’t fully capture the riot of neighborhoods and interest groups and social classes within its boundaries. It almost seems calculated to make a mockery of the Founding Fathers’ idea that a congressional district should constitute a community of interest. Politically, the apt term is “balkanized.” Pasadena has always been a hotbed of feuding factions, the unions hold some sway on the east end, and the black community has an indigenous power structure still centered in its churches. But there’s nothing even remotely resembling a political boss for the district: asked to name the most powerful person within its boundaries, both Andrews and Faubion drew a blank. In short, the 25th District is just the sort of power vacuum that outside forces inevitably rush to fill.

So the how and why of Mike Andrews’ victory is more than a tale of what it took to get elected to Congress in Texas in 1982—although it is that. The process by which the 25th District’s seat was filled also revealed the varied interests that care—a lot—who represents southern Harris County in the national legislature, and why they care. What was really at stake in the long campaign was power: for the candidates, the power to become overnight a figure of importance in Texas, with a bright future as a player on a very broad field; for interested parties from the union halls of Pasadena to the boardrooms of Milam Street to the White House, the power that comes from having a voice in Washington and a vote in a tightly divided Congress.

A Bright Young Man

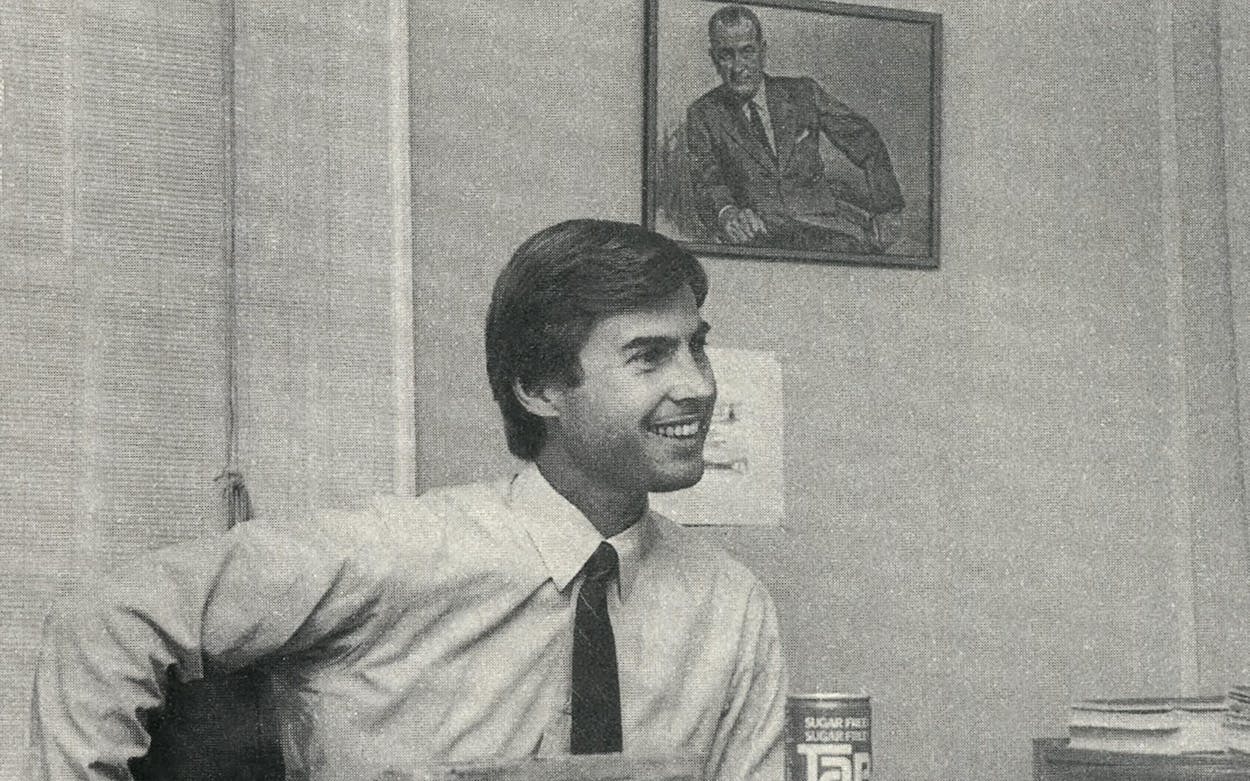

The rap on Mike Andrews is that he’s nothing more than a puppet of Houston’s downtown business establishment, and while that’s not true, his success does illustrate the unsurprising notion that it never hurts to have friends in high places, particularly if those friends need something and you can provide it. In this case the something is a congressman who’ll be an insider rather than an outsider, someone suited by inclination and ability and party affiliation to work with the House leadership and, in the process, to look after Houston’s interests. In 1980 that person didn’t exist; Bob Eckhardt wasn’t inclined, Mickey Leland didn’t seem able, Bill Archer was of the wrong party, and Ron Paul suffered from all of the above afflictions. Paul—whose 22nd District then took in most of the current 25th as well as Fort Bend and Brazoria counties—is the very antithesis of a team player. Any reasonably bright, reasonably attractive, reasonably personable, reasonably eager candidate who had been willing to challenge him would probably have found favor downtown. And Mike Andrews is more than reasonably bright, much more than reasonably attractive, and extremely personable in an ebullient, self-effacing way that nearly hides the ferocity of his drive to win.

In January 1980, when, at the age of 36, he announced his first congressional campaign, he was also unknown, untried, and very green. Nothing in his background particularly marked him as congressional material. He grew up in modest neighborhoods on the west side of Fort Worth as the son of a watch repairman and a schoolteacher. He went to the University of Texas and then to law school at SMU, clerked for a federal judge, worked for the Harris County district attorney’s office, and became a partner at the downtown Houston firm of Baker Brown Sharman Wise & Stephens. He first had the idea of running against Ron Paul on November 7, 1978, the day Paul took—or retook—the 22nd District seat from Democrat Bob Gammage.

On that day he began to lay groundwork, first ascertaining that none of the Democratic machines in the district were strong enough to prevent a party newcomer like himself from running, then assembling the coterie of friends that would form the nucleus of his campaign. Vic Driscoll, whom Andrews had worked with for four years in the D.A.’s office, was a nephew of Ralph Yarborough’s; he had cut his political teeth during Yarborough’s various runs for the Senate and the governorship. Chuck King, who had been to UT law school and met Andrews through friends, worked for one of the state’s most politically active law firms, Bracewell & Patterson. Dick Trabulsi, a lawyer and liquor retailer who had also graduated from UT, had run Jimmy Carter’s 1976 Gulf Coast campaign. But none of them had ever undertaken anything on the scale of a challenge to an incumbent congressman in an urban media market—a feat that would require not only skill, dedication, and luck but also well over half a million dollars.

Andrews announced his candidacy for the Democratic nomination in January. In February Bob Gammage threw his hat into the ring. Andrews’ own poll estimated Gammage’s name identification at 70 per cent; Andrews’ was only 3 per cent. One of Andrews’ staff called the hotel of his Austin-based campaign consultant, from the firm of Martin-Rogers Associates, only to be told that the man had checked out the day before. Frantic phone calls to Austin elicited a letter that said in essence: we only work for winners, and you can’t win.

Andrews knew his opponents were vulnerable, however. The third Democrat, Joe Pentony, had liberal ties that were hardly calculated to endear him to downtown, and Gammage’s performance in Congress had been lackluster in the extreme. So while the world at large wrote off Mike Andrews, he quietly went about winning over not only the voters of the district but the powers that be. Through Trabulsi he cultivated oilman and Carter stalwart Jack Warren, cofounder of Houston’s largest privately held corporation, Warren-King Companies, and one of the heaviest hitters in Houston political financing. Andrews’ finance chairman, another UT ex named Bob Parker, is a young Turk at the investment counseling firm Fayez Sarofim. Sarofim is a son-in-law of George Brown; Parker’s father had been president of Brown & Root. Parker’s first act as a fundraiser was to introduce Andrews to Brown over lunch at the Ramada Club. The man who had bankrolled Lyndon Johnson’s rise to power was sufficiently impressed with Andrews’ discourse on why Paul was beatable—or perhaps with the young candidate’s earnest deference—to pledge $1000, the maximum allowed by law.

Next Andrews and Parker approached developer and Allied Bancshares chairman Walter Mischer, reputedly Houston’s canniest political kingmaker. “We were so naive,” says Andrews, “we thought all we had to do was win over Mischer and the financing would be taken care of.” Again their pitch did the trick—sort of. Mischer wrote out a check for $1000. “I looked over at Parker and I could tell he was really pumped up,” Andrews recalls. “He turned to Mr. Mischer and said, ‘Well, sir, where do we go from here?’ and Mischer pulled out the Houston white pages and said, ‘This is a pretty good place to start.’ After we left his office, Parker and I just stood on the street corner, looking at each other and wondering what to do.”

What they did was start soliciting Andrews’ friends, mostly up-and-coming lawyers but also the scions of some of Houston’s most prominent men—Corbin Robertson, Jr. (grandson of Hugh Roy Cullen), Lan Bentsen (son of the U.S. senator), Jeff Love (son of the chairman of Texas Commerce Bancshares). Then they sank $25,000 into a series of basic, ten-second, “Hi, I’m Mike Andrews and I’m running for Congress” TV commercials. Suddenly they had a legitimate candidate on their hands; the big donors and political action committees began to take an interest. “We found,” says Andrews, “that the way to raise money was with mirrors.”

Mirrors like television. Though it has been condemned as too expensive and too superficial, television is practically indispensable for a newcomer going up against an incumbent—especially a newcomer like Mike Andrews. The TV camera plays favorites: it likes some people better than others, and Andrews it likes very much. Through no particular skill or inner virtue, he is compelling on television, a phenomenon that has been pointed out often enough to embarrass him but that he’s far too shrewd not to exploit.

In the primary of 1980 Andrews’ TV presence, his aptitude for fundraising, and a blitzkrieg get-out-the-vote effort pushed him past Pentony and into a runoff with Gammage. He beat Gammage by outspending him five to one, then prepared for a frontal assault on Ron Paul. He hired veteran Democratic strategist George Christian to pinpoint Paul’s weaknesses. Once again the main weapon was TV. Andrews attacked Paul’s votes against defense funding and his neglect of local projects in a series of elaborately produced, on-location spots that featured the tag line “Ron Paul is the wrong man in the wrong place at the wrong time.” A few days out, Andrews’ polls said the race was too close to call. Then, in one of the great, gut-level shifts of American politics, the voters of the 22nd District, like voters nationwide, rose up to repudiate Jimmy Carter and embrace Ronald Reagan, and Mike Andrews lost by a margin of 5500 votes, all of them outside Harris County.

The Battle of Austin

Then the gods of politics gave Mike Andrews a once-in-a-decade opportunity: redistricting. The 1980 census had determined that Texas would get three new congressional seats, one of them either partly or wholly within Harris County. That meant Andrews could run again without taking on Paul or any other incumbent. If, that is, the new district ended up in the right place and had the right boundaries—if Andrews could pull a string or two in Austin.

Of course, he wasn’t the only one whose ambitions were at stake. To start with, there were the four Houston incumbents; none of them would want to give up territory to a new district if their own districts became less friendly in the process. Then there were the other Democrats who might want to run; of these the most prominent and frequently mentioned was longtime state senator Chet Brooks of Pasadena. On the Republican side, at least two state representatives, Brad Wright and Don Henderson, had their eyes on the new seat. And complicating things even further was the statewide struggle between the two parties taking place in the Legislature.

Andrews’ strong showing in 1980 and his connections to the likes of Mischer and Brown made it unlikely that the Legislature would ignore his interests altogether, but he was hardly assured of getting precisely the district he wanted. That district, he decided, would encompass black neighborhoods from the districts of Leland and Paul, the southwest quadrant of Harris County, and a chunk of Brazoria County, which—1980 to the contrary—generally voted Democratic. He drew up a map, took it to Austin, and showed it to several people, including Lieutenant Governor Bill Hobby. Something very like Andrews’ map got incorporated into an early version of the Senate bill, but then Chet Brooks, part of whose power base in Pasadena had been left out of the new district, began to work for changes.

As things turned out, it wasn’t hard to strike a compromise that both Andrews and Brooks could live with and that also accommodated the incumbents’ desires. In order to create a district that favored a Democrat, the Democratic party sacrificed a chance to make life uncomfortable for Republicans Paul and Fields. The Republican party managed to protect its incumbents, which was as much as it could reasonably hope for, considering its already disproportionate strength in the delegation. Republican senator Mike Richards did mount a last-ditch ploy to remove Andrews’ house from the 25th District—a ploy that failed to pass the Senate by one vote, Hobby’s tie breaker—but later, when George Brown phoned Andrews to ask if he was happy with the district, he could answer that he was.

The Republicans

The ink on the redistricting map was hardly dry when the pollsters and demographers and political consultants began to descend upon the district. Some worked on behalf of would-be candidates; one, Lance Tarrance, labored in the service of the Republican National Committee (RNC). Politics, it has been said, is the triumph of hope over experience: the 25th District is, by any traditional measure, a Democratic district; nevertheless, the RNC was willing to spend a great deal of money to procure a statistical analysis the size of the Houston yellow pages that would suggest otherwise. And since the national Republican party consistently outraises, outspends, and outorganizes its Democratic counterpart, the RNC was able not only to finance the study but, as the race wore on, to contribute vast sums of money to its candidate. But the most important thing about Tarrance’s poll was that Tarrance did it. Until he miscalled the recent Texas governor’s race, Lance Tarrance was one of the hottest Republican pollsters in the country, so hot, in fact, that some people wouldn’t give money to a candidate unless Tarrance said he or she could win.

Tarrance told the national committee that the respondents to his poll, taken in November 1981, thought highly of Ronald Reagan and his economic policies and described themselves as conservative. He also told the RNC, among other things, which issues people were most concerned about (crime and inflation), which kinds of radio and TV they tuned in to (easy listening and country; news) what they thought about an anti-abortion constitutional amendment and defense spending cuts (they opposed both), and whether they had made a personal commitment to Christ (56 per cent said they had). Meanwhile, at the University of Houston, Richard Murray, working on behalf of Mike Andrews, looked at the district’s demographic profile and its voting history and concluded flatly that a Republican had no chance.

By the March 12 filing deadline for the primaries, the 25th District was sprouting campaign headquarters like mushrooms: seven Republican, three Democratic, one Libertarian, one Citizens party. First out of the blocks for the Republicans was a big, genial, handsome dry cleaning entrepreneur named Larry Carroll. Carroll, hired a young woman from the National Republican Congressional Committee (NRCC) as his campaign manager, signed up Lance Tarrance as his honorary chairman, and mailed out a type-heavy, eight-page campaign brochure with a full-color photo of the space shuttle on the cover. All of which was enough to make him look like the front-runner but not enough to bring the big money off the fence when he found himself running against six other candidates rather than one or two. Carroll’s major competition was expected to come from J. C. Helms, a Harvard-educated classicist turned developer. Helms got into the race late, but his ties to River Oaks money and his record of party service made him a contender.

Two of the Republican candidates had actually run for office before. Larry Washburn, a civil engineer, had been drubbed in the 8th District’s Democratic primary by Bob Eckhardt in 1980, before Eckhardt was drubbed by Jack Fields. Dick Burns, a lawyer, had nearly won a state district judgeship in 1980. Burns clinched the early-visibility sweepstakes with a rash of billboards and assured everyone that he could win the race without a runoff, but that was about the extent of his campaign.

Two of the three remaining Republicans clearly didn’t have a prayer. Everything about computer programmer Pat Angel, from her conspicuous lack of ego to her “Elect an Angel” slogan, screamed noncontender. Joseph Jefferson Burris, a retired city engineer, campaigned on a platform calling for, among other things, an end to the national income tax and the reinstatement of the Republic of Texas.

In the beginning, you would have had to rate Mike Faubion somewhere between Washburn and Burris—that is, between the marginal and the hopeless. Faubion was just 33, he had no political ties to speak of, and although his civil-law practice brought in a comfortable living, he was hardly a wealthy man or an intimate of wealthy men. He didn’t have Mike Andrews’ entrée, and he didn’t have Andrews’ talent for asking for money. But a Republican primary in Texas is different from any other kind of election because so few people vote in it. No more than 10,000 Republicans were expected to go to the polls in the 25th District on May 1; if Faubion started early enough, he could knock on 10,000 Republican doors by that date. He raised $10,000 from family and friends and approached Houston consultant Paul Caprio for advice on how to design a push card (so called because it is pushed into the hands of voters) and to order a walk list.

Lists are the sine qua non of every modern political campaign. The kind Faubion began with reflect a person’s voting history—which primary elections he or she has participated in. But if a candidate wants a list of people in a certain income bracket or a certain business, or who own homes, or who practice a particular religion or avocation, chances are excellent that that list exists. Every time you deal with a mortgage company, join a professional society or fraternal group or church, subscribe to a magazine, or acquire a credit card, your name is likely to wind up on another list that is for sale.

In December Mike Faubion got his push card and his street-by-street list of Rs (people who had voted in one of the last three Republican primaries), RRs (voted in two), and RRRs (voted in all three) and prepared to announce his candidacy. Paul Caprio came to the event to tell Faubion as a hedge against future campaign expenses, the consultant would have to withdraw. Faubion said there wasn’t $25,000 and Caprio said good-bye. On January 4, Mike and Tamara took to the streets as scheduled, knocking on doors from mid-afternoon until nightfall.

But no one, no matter how determined, can run for Congress without a staff. In January state Republican party director Tom Hockaday mentioned Faubion to a young man named Kevin Burnette, a UT economics graduate who had worked in John Tower’s 1978 senatorial and John Connally’s 1980 presidential campaigns. He and Faubion met. Then Burnette contacted Denis Calabrese, a senior economics major at Rice, and Lee Woods, a buddy from UT who was in the business of rounding up investors for oil and gas ventures. Woods and Burnette were 25, Calabrese 22. All three were intensely hungry, all three were intensely conservative, and all they knew about Mike Faubion was that he seemed as conservative and as hungry as they were.

They were young but not unschooled in the ways of politics. In addition to pouring money into campaigns, the national Republican party and several conservative organizations have built a cottage industry around educating candidates and staffers; Burnette and Calabrese are among a small army of eager young conservatives who are products of such campaign seminars. Faubion had entered the race planning to sell himself as the hardworking hometown boy; his young aides turned him into the candidate of ideas. By mid-March he was greeting visitors to his office with a rapidfire stream of policy statements—on a constitutional amendment to balance the budget, six-year terms for federal judges, federal sunset laws, block grants for flood control projects—still coming across as just a trifle callow, perhaps, but gaining conviction with every recitation.

The Democrats

“Callow” is not a word one would apply to state district judge John Ray Harrison. The judge, formerly a Democratic state legislator and mayor of Pasadena, is just about as imposing as a slow-moving, slowtalking good ol’ boy who says “thew” for “through” and “wonst” for “once” can be. Harrison announced in December and by March had four-by-eight-foot signs up on what seemed like every street corner east of the Gulf Freeway. His idea was that the east-end cities of Pasadena, Deer Park, and La Porte could at last elect one of their own to Congress. Chet Brooks had decided not to make the race (his Senate seat was safe, Andrews’ establishment support was formidable, discretion was the better part of valor), so the obvious choice was John Ray Harrison. The numbers Harrison used to illustrate his contention—that if 90 per cent of the voters in Pasadena turned out, and if 90 per cent of those voted for him, he would triumph—were a little hard to swallow. But if he was correct, that meant Mike Andrews had failed badly to protect his interests during redistricting. By Andrews’ reckoning, the district wasn’t supposed to elect a black or an east-end candidate; it was supposed to elect someone without a specific constituency, a classic middle-of-the-road candidate like Mike Andrews.

To some degree that description also fit the third Democrat in the race; in his nineteen years in the Legislature and on the Harris County Commissioners’ Court, Tom Bass had represented nearly all of the precincts that made up the district. Bass, a wry, spare, somewhat pedantic alumnus of the Legislature’s post-Sharpstown reform crowd, figured he couldn’t do worse than come in second, even though—in the best liberal grandstanding tradition—he had vowed not to spend more than $50,000 on this primary that was supposed to cost at least $200,000.

That was not Mike Andrews’ approach. With redistricting behind him, Andrews moved swiftly to shore up his financial base, beginning in early December with a $1000-a-head reception at the Houston Club whose list of eighty “sponsors” was so loaded with prominent names—including Texas Air chairman Frank Lorenzo, Texas Commerce Bancshares chairman Ben Love, and champion Democratic fundraiser Jess Hay as well as Mischer and Brown—that it prompted one wag to concoct a parlor game called Name the Missing Fat Cat. Harrison and Bass did their best to use Andrews’ list of supporters against him, giving copies to reporters and muttering darkly about debts and influence, but to little apparent avail. Then, while his opponents acted as their own managers, Andrews went after the pros: Richard Murray as analyst, former Houston Natural Gas lobbyist George Strong as manager, adman Roy Spence as media consultant, national expert Mary Ellen Miller as phone-bank director, rising Democratic star George Shipley as pollster, and George Christian as all-purpose sounding board and eminence grise. Plus, of course, unofficially, Vic Driscoll, Dick Trabulsi, Chuck King, Bob Parker, and Jack Warren’s political money raiser, Bill Wright.

Round One

A primary with this many candidates unfolds with all the finesse of a barroom brawl. Nobody knows quite whom he’s fighting, so there are lots of wild punches and unforeseen collisions. Among the Republicans, J. C. Helms came on strong, as expected, with direct mail and radio spots in the last ten days, and on May 1 he walked away with 3441 votes, or 34 per cent. Larry Carroll, whose socko start proved to be his downfall—his campaign overspent itself early and couldn’t counter the others’ late pushes—took third with 16 per cent. After running virtually no campaign at all, Larry Washburn unleashed four good, solid mailings during the final week and emerged a surprisingly strong fourth. Burns, Angel, and Burris fizzled according to schedule. And Mike Faubion, who had also mailed heavily during the last ten days—one letter bluntly disparaged Helms’ chances of beating a Democrat in November—surprised almost everyone outside his own campaign by waltzing into the runoff with 2494 votes, or 25 per cent.

If there were any surprises in the Democratic primary they were merely of degree—that Andrews did so well and Bass so poorly. The commissioner, who had set out to prove that a congressional race could be run like a local race, spent $45,000 to prove himself wrong. He came in third with 6568 votes (27 per cent). Harrison, who relied heavily on advertising in east-end newspapers to supplement his signs, polled 65 per cent in Pasadena–Deer Park but got buried by Andrews elsewhere, winding up with 30 per cent to Andrews’ 43 per cent.

For a quintessential media candidate, Andrews hadn’t run much media. There had been an early round of billboards and a slick eight-page brochure that featured the world-class something-for-everyone slogan “He thinks like you do.” But he used only one week of sporadic TV, perhaps because the price of a thirty-second spot had jumped 40 per cent since 1980. In fact, the television kid had won with a back-to-basics organizational campaign: key endorsements (by everyone from black politicos Mickey Leland, Craig Washington, and Anthony Hall to the Houston Chronicle); day after grinding day of Rotary luncheons, door-to-door campaigning, civic club meetings, and neighborhood coffees; and, above all, sophisticated phone banks to identify and turn out favorable voters.

Accusations

Runoffs breed hysteria. The problem is that people don’t vote in runoffs—they’ve done their duty once and they’re just not interested. So the campaigns crank up the volume from strident to shrill to catch the public’s flagging attention. J. C. Helms set the pace by running not against Faubion but against Andrews. He challenged the Democrat to a debate and ran ads in the Pasadena and Deer Park papers attacking Andrews’ endorsement by Mickey Leland. Meanwhile Faubion sent all his troops into Clear Lake City, where he had been beaten badly in the primary, and hit Republican voters with a last-minute spate of anti-Helms mail. The four mailers, all a forbidding black, attacked Helms for being a bachelor, for having moved into the district to run, and for possessing a Harvard degree, factors Faubion said would drive away the swing voters who were the key to winning in November. Helms’ complacency in the face of Faubion’s relentless attacks gave Faubion the win on June 5 with 54 per cent of the vote.

On the Democratic side, Harrison and Andrews kept busy heaving accusations of radicalism and racism at each other across the Gulf Freeway. Andrews looked all but impregnable in the western end of the district, where Harrison’s tool-of-the-downtown-establishment line was falling flat. The judge’s only chance was that the west end would forget the race while the east end stayed stirred up. And his opponent had handed him just the thing with which to stir it. Andrews had run an ad in a black newspaper that showed him embracing Mickey Leland under the headline WE THINK A LOT ALIKE. Harrison issued a press release to the east-end papers, playing on Leland’s early radical posturing and painting Andrews as the next-best thing to a Marxist revolutionary. To top it off, Harrison accused Andrews of having dispatched a sound truck into black areas to urge voters to “send the redneck back to Pasadena.”

Andrews hurriedly ditched the “We think alike” slogan and denounced Harrison and Helms for attempting “to polarize our district along racial lines.” He also called Harrison a puppet of the New Right for having accepted $5000 from the National Conservative Political Action Committee, the infamous NCPAC. The newspapers loved it; day after day the latest barrage from each side landed on the front page of the Pasadena Citizen. Harrison’s strategy had worked—up to a point. The turnout in Pasadena and Deer Park was higher on June 5 than it had been on May 1, and the judge got 70 per cent of those votes. But all the hoopla had aroused Andrews’ voters, too; the final tally was Andrews 11,011, Harrison 8029.

Rich Friends

Summer is a time in campaigns for fence mending and stock taking, for fattening up the treasury and laying out the battle plan for the long ordeal ahead. Scarcely had the last vote been counted than Faubion and Andrews were in the east end, scrambling to win over Harrison’s best-known supporters. Both also commissioned polls over the summer, Andrews from Shipley and Faubion from Tarrance. The polls showed that the issues in the election were national and, by extension, that what the national Democrats and the national Republicans said about them, particularly unemployment, was as important as anything Mike Andrews or Mike Faubion said.

In any case, neither candidate seemed likely to galvanize the electorate with his personal vision of the nation’s future. Faubion had an agenda, but it differed very little from the standard Reaganite line; oddly, as the president’s popularity waned, Faubion seemed to embrace his rhetoric more and more. As late as the final week he was still trying, unsuccessfully, to convince Reagan to campaign for him. Andrews shrewdly stuck to unemployment and social security, playing on the age-old theme of the Democrats as the party of compassion. The ideological difference that communicated itself most forcefully throughout the campaign was in the candidates’ attitudes toward government and politicians. Mike Andrews met Gary Hart and John Glenn and came away impressed by their intelligence and integrity. Mike Faubion met George Bush and Ronald Reagan and had the insight that “they’re only men after all.”

Without indulging in undue psychologizing, it’s fair to say that Andrews is fundamentally an insider in a way that Faubion is not. Andrews had been instinctively readying himself for this race at least since college. In fact one way to define the difference between the two men is to say that Andrews went to the University of Texas and Faubion went to the University of Houston; UT was a common thread that linked Andrews, Parker, Trabulsi, and King to an unmatched statewide web of money and power. Andrews had made the right friends, chosen the right jobs (the D.A.’s office has political overtones, corporate law brings one into contact with the rich and powerful), joined the right breakfast clubs and country clubs (River Oaks), bought the right house (near Rice), showed, in short, that he appreciates how the game is played in Houston. It was vital that he communicate this to the city’s establishment because, in the final analysis, this race was a power struggle between Houston’s traditional leadership and the national Republican party. Political and business leaders within the district did play a role, but it was largely symbolic. Almost all of the money came from outside.

Basically, there are three sources of political money: rich people, friends of the candidate (or friends of friends of the candidate), and political action committees. The PACs, groups of like-minded individuals who pool their money, can give up to $5000 to a candidate, five times the limit on an individual’s gift. There are all sorts of PACs: industry, labor, conservative, environmental, feminist, you name it. But the outcome of the 25th District race hinged on the involvement of the business PACs—which had, for instance, given Jack Fields $270,000 to help him defeat liberal Bob Eckhardt in the neighboring 8th District in 1980.

Faubion was trailing; he needed to raise more money than Andrews just to catch up. PACs are utterly unsentimental, however; they only give to candidates they consider viable. So first Faubion had to convince the business PACs that he could win in spite of the polls, which showed Andrews leading by between 32 and 44 points. On the other hand, donors, and political action committees in particular, don’t like to give money to sure winners (why pay to put someone in office if he’s going to be there anyway?), so Andrews’ fundraising was in jeopardy as well.

The signals had been there as early as the primary, when Andrews’ media blitz failed to materialize as expected. In truth, the money just wasn’t there, not for him or for anybody; the economy had gotten that bad. And now, with the Houston business community split—Faubion did have a few heavy hitters in his camp, notably homebuilder Bob Perry—many of the big PACs had little choice but to stay on the sidelines. “The Andrews-Faubion race caused me a lot of grief,” says Jack Webb, executive director of HOUPAC, Houston’s leading business PAC. “We had a bunch of people on both sides leaning on us, saying, ‘You give this boy some money.’ We had to say no to some people you don’t like to say no to.” The grief was merely temporary, however. “The PACs really couldn’t lose on this one,” says Webb.

In 1980 Mike Andrews had spent $608,000 running against Gammage, Pentony, and Paul. Paul had spent $640,000. Now, in the late summer of 1982, Andrews confided that he might have no more than $120,000 with which to wage his fall campaign. Faubion by mid-October had received nearly $57,000 from the NRCC, the RNC, and other Republican and conservative groups. But other than those infusions and a limited amount from business PACs, the Republican wasn’t faring much better than the Democrat and was, in fact, digging deeply into his own pockets.

A dearth of money wasn’t the only way 1982 was different from 1980. Running against Paul, Andrews had been the underdog, always on the attack. Now he was the certified front-runner, the target for a candidate who had demonstrated a relish for hardball. Since any misstatement or seeming contradiction was sure to be seized on as proof of insincerity, it was best for him to say as little as possible. Short of money, knowing that the attack would come but not knowing precisely what it would be, Andrews was forced to play defense—being careful, of course, not to appear defensive. George Strong, whose strengths are media and strategy, stepped out of the manager’s role; Vic Driscoll, a steady, methodical organizer, stepped in. The campaign brochure was scaled down to four pages. Plans for TV were put on hold. Even some of his own supporters began to wonder aloud why Mike Andrews wasn’t waging a more aggressive campaign.

Worrying

Faubion wasn’t likely to win the race, but Andrews could still lose it. So far he’d escaped from blunders like the Leland“We think alike” ad remarkably unscathed. But if Faubion could scrape up enough money to get on TV and could play effectively on the class issue Harrison had exploited, and if Andrews ran out of money and made any major errors, the complexion of the campaign could change in a hurry. Most of all, said Kevin Burnette, “I just don’t want to wake up on November third knowing there was something I could have done that I didn’t do.” So as their campaigns went public again in September, both candidates were running hard and, to some degree, running scared.

Nine months of campaigning had battered all traces of callowness out of Mike Faubion. As he sat in his rather shabby storefront offices near the Medical Center in early October, smoking and letting his mind play over the shape of the campaign, he still exuded the impatience of the true believer but no longer the impatience of youth. Weariness had burnished the edges of his personality into even more prominence. Let others say his cause was hopeless; with satisfaction he examined the bulwark of stratagems that insulated him from their nonbelief.

He had gone to an NRCC candidate school in Washington. He had run TV—in August, no less, long before the herd of candidates had come bawling into Texans’ living rooms. The NRCC had paid $18,000 for seventeen airings of a commercial, filmed in a machine shop, in which a man told voters that Mike Andrews was a slick opportunist and Mike Faubion was a straight guy. He had gone to Israel, demonstrating to the Jews in the district that not only Democrats cared; that might even win him the endorsement of the Jewish Herald Voice. His staff had divided the precincts in the district into four categories—Jack Fields’ old precincts, Republican precincts, Pasadena, and Democratic precincts—and targeted the first three for as many as six pieces of direct mail. His phone banks were busy every night, and they showed that far from trailing Andrews, he held the lead. True, the phoners were using what are known as advocacy calls, making a direct pitch (“Mike Faubion has been endorsed by Ron Paul and Jack Fields, while his opponent is supported by Mickey Leland. Can I tell Mike Faubion that he can count on your support on November second?”) rather than simply asking whom the citizen planned to vote for. But how misleading could the results be?

Andrews didn’t know about Faubion’s phone results, and he believed he was still ahead; but he never relaxed. In early October, taping a local Issues and Answers program with Faubion, he worried about what to say in his opening remarks. He fidgeted on camera as Faubion accused him of fuzziness. (Vic Driscoll, watching on a monitor and buoyed perhaps by the sight of his candidate on TV, was characteristically calm. “Look at Faubion sneer,” he said. “He thinks he’s really put Mike in a box.”) Later, taping his first radio commercial, a nice soft spot about social security that stressed his compassion, the candidate fretted that his delivery wasn’t exactly right. Driscoll liked take seven. “Let me do it again,” Andrews insisted. Take twelve sounded fine. “No, let’s do another one.” and another, and another, up to take twenty—which really was better than the rest.

By mid-October the Faubion onslaught was in full swing. There were ads in the Pasadena Citizen denouncing Andrews’ supposed inconsistencies (which in private Kevin Burnette cheerfully admitted were negligible) and branding him a big-spending liberal. For Republicans, there was a pro-Faubion letter from George Bush and a mailer that proclaimed, “The race between Mike Andrews and Mike Faubion . . . is really a fight between Tip O’Neill and Ronald Reagan.” In Jack Fields’ old precincts the mailer stressed Fields’ endorsement of Faubion. Pasadena got a special version of a crime piece that went elsewhere and two pieces that exploited the issues of class and race that Harrison had harped on, contrasting Faubion’s working-class roots with Andrews’ posh address and country-club membership and resurrecting the Mickey Leland endorsement. “I’m more like you,” Mike Faubion assured the voters of Pasadena. And he was right.

Faubion’s strategy had been laid out for months, but now a new urgency fed his attacks. At the suggestion of the RNC and NRCC, Kevin Burnette had stopped making advocacy calls and begun actually polling. The numbers looked far, far worse. He had known Faubion wasn’t really ahead, but the new numbers showed him barely holding his own even in some of the Republican precincts. And Pasadena, so vital to their plans, was a huge, worrisome cipher—almost 50 per cent undecided.

Andrews’ phone bank had been making advocacy calls, too, but it was run by a company whose founder, Mary Ellen Miller, had invented phone banks —under the auspices of the RNC, no less. While Faubion’s staff laboriously tabulated each night’s results by hand, Andrews’ numbers were fed to a computer in New Orleans. Miller had also developed complex methods for estimating how many of the respondents were telling the truth (rather than saying yes or no to get the pollster off the phone) and which way the undecideds would break and who would actually vote. So Andrews knew he was holding his own. But still he worried: when would Faubion’s real attack come and what would it be? Andrews favored delaying the next round of tax cuts; would Faubion hit that? Andrews had defended one of the Houston policemen accused of drowning a Mexican American prisoner in the mid-seventies; would that be it? Thus far he had not reacted to Faubion’s needling, and that had been the smart course. But sometimes, when the accusations got serious enough, you had to strike back, if only to make your own people feel better.

Kevin Burnette worried too. Faubion had mail hitting throughout the district; Faubion was all over the radio dial with spots denouncing Andrews as a country-club swell and spots featuring Eddie “I’m Mad” Chiles, spots introduced by Reagan and spots saying Andrews was going to take away the people’s tax cuts. And the numbers just weren’t moving.

Burnette perked up momentarily when he went to the printer on October 25, just eight days out, to inspect the final round of mail pieces—he was particularly proud of the ones aimed at Mexican Americans and blacks, which began with the questions “are you about to vote for the man who defended the killer of Jose Campos Torres?” and “Will Mike Andrews protect your civil rights in Congress?” But back at headquarters, as the evening wore on, he grew quieter and quieter. Finally he sat, his elbows on his knees, staring at the floor. “I just don’t know how to beat this guy,” he said at last. “We’ve done everything. I don’t know what’s happening, but the Pasadena precincts tell me it’s not moving as it should.” He nodded to the next room, where Tamara Faubion’s mother and father were stuffing envelopes. “Look at those people in there. They got into this because I told them they could win.”

The Last Minute

On Tuesday, one week before election day, Faubion gathered the press on the steps of Andrews’ Pasadena headquarters and challenged the Democrat to produce a written endorsement from John Ray Harrison. Thus far, Harrison’s conspicuous absence from the race had been only a minor irritation to Andrews; Faubion was trying to make it a substantial embarrassment. The judge had told Faubion’s people, or they thought he had, that he would not restate the cursory endorsement he had given Andrews after the runoff.

The following afternoon, Wednesday, Faubion greeted a throng of steelworkers as the shifts changed at ARMCO’s huge Pasadena plant. These were the very people who Lance Tarrance and the RNC had been assuring the world could be won over to the Republican party, but across the street, the sign on the union hall marquee read: “Remember Reaganomics—Vote Democratic.” Most of the workers were friendly as Faubion grabbed their hands—unless, that is, they thought to ask which party he represented. “Go to hell,” they told him then, or “Who’s your opponent? He’s my man,” or “I made that mistake the last time around,” or “Ugh, now I have to go wash my hand.”

On his way out Faubion made a call back to headquarters. All was not well. “What’s happened?” he asked. “He did?” That morning, at a press conference in Pasadena, John Ray Harrison had endorsed Mike Andrews. The challenge to Andrews had blown up in Faubion’s face. The candidate began to laugh thinly as he headed for his car. Twenty minutes later he and his aides were closeted in an office with Republican state representative Randy Pennington, who had been acting as an unofficial advisor to the campaign. Faubion looked on morosely as his fundraiser, Lee Woods, called an acquaintance at the Chronicle to find out how the news of the endorsement would be handled. Then Pennington called Bob Perry, who had supported Harrison before becoming Faubion’s chief financial backer, and asked him to call the judge. Tell Harrison to phone the Pasadena Citizen, Pennington urged Perry. Tell him to say nice things about Faubion and ask that the endorsement be downplayed.

If Harrison did make the call to the paper, it didn’t work. The Citizen put the story exactly where it had put the news of Faubion’s challenge, right in the middle of the front page. So the next day, Thursday, began well for Mike Andrews. He breezed into Bill Wright’s office in the mood to raise a lot of money. They reviewed the list of people who had promised to contribute but had not yet sent checks. Then they went to work on the phones, sounding for all the world like two backslapping good ol’ boys expertly working a crowd.

“Hi, podner! How you been?” Wright bellowed good-naturedly at one of the laggards. “Mike Andrews needs money.”

“That’s right,” Andrews confirmed on his extension. “I’m at Wright’s office. Bring sacks of money.”

Wright chuckled. “One check will do —one with three zeroes on it.”

Back at Andrews’ headquarters the morning quickly went sour. The candidate sat down heavily and stared at the mailer on his desk. “Are you about to vote for the man who defended the killer of Jose Campos Torres?” it demanded. He read it slowly, carefully, then wearily turned it over and studied each page again. “I don’t think it will hurt,” he said softly. “I’ll kill him in the black community. I’ll get 95 per cent. If he were smart he’d run black radio too.” He paused, then began to examine the piece again. “I just don’t know how to judge. I’m so tired.”

Thursday afternoon, while Andrews’ staff wrestled with what to do about the Torres mail, Mike Faubion went into the studio to cut a spot for black radio. Fundraiser Lee Woods had nixed the idea for lack of money earlier, but after the Harrison endorsement fiasco he had relented. Faubion’s script pulled no punches. Mike Andrews “is a fake and a hypocrite,” he intoned with relish.

“We’ll outkick Andrews,” Kevin Burnette gloated. “We’ve got Eddie Chiles doing some really rabid antiliberal spots against Andrews to run in Pasadena. And rednecks don’t mind negative campaigning, I don’t care what you say.”

That same evening, Mike Andrews’ steering committee met to review election-day strategy and receive Richard Murray’s projections. The candidate looked utterly tired but utterly determined. He and a black staffer had just made a radio spot to rebut the Torres mail. The discussion turned to whether 75 phones were absolutely necessary on election day; the campaign could save $2400 by having only 40. Andrews was adamant: there would be 75 phones.

Murray saw no way Andrews could lose. “Faubion’s attacks have no predicate,” he assured the group. “He needed at least three weeks of TV to establish his name ID. People are saying, ‘Who is this Faubion guy?’ What he’s doing would have been great in eighty, but he’s two years too late.”

Black Sunday

Now, with only four days left, the campaigns hit an odd sort of dead space. The die was cast—the mail was out, the radio spots were running, the debates and speeches were over. There wasn’t much to do but phone and walk and try to stay upright. On Halloween morning, with two days to go, Andrews and his wife did what he had often done during the past several months: they made the rounds of black churches in the district. At the Brentwood Baptist Church the candidate sat very still as the words of the sermon rolled over him in great sonorous waves: “Every problem is an opportunity. The walls will come down. The rivers will divide. The giant will fall.”

They visited three other churches, and at each one he was permitted to address the congregation. At the Mount Hebron Baptist Church, moved by the soaring harmonies of the gospel choir, he gave perhaps the best speech of his campaign, rocking toward his audience with every phrase.

“I’m a Democrat,” he told them. “I’m proud to be a Democrat. The Republicans will tell you things are about as good as they are going to get. I don’t believe that.” He told them then how he had been scolded when he was ten years old for drinking from a water fountain marked “Colored.” “How far we have come,” he said. “How far we have to go.” and then he quoted Theodore H. White quoting John Kennedy in 1960, who was quoting from a letter written by Abraham Lincoln. “I know there is a God, and I know He hates injustice. I see the storm coming, and I know His hand is in it. But if He has a place and a part for me, I believe that I am ready.” A soft chorus of Amens told him they were with him now, and he closed while he had them. “Tuesday is election day,” he said. “I need your vote. We need your vote. Go vote. Go. Vote.”

The Verdict

Vote they did. In the muggy early morning of November 2 the polls of Southwest Houston hummed, but that was to be expected. The Republican suburbs always vote and vote early. As one drove eastward across the district, however, the surprise began to mount. There were people at the polls in the black precincts, lots of people. Pasadena was turning out too, and an exit poll by the Pasadena Citizen showed a remarkable number of straight-ticket Democratic votes. By early afternoon a wall of slate-gray clouds was advancing from the northwest. At Andrews headquarters Chuck King was playing ringmaster, sending out two-person teams to walk precincts and get out the vote. In the lulls he took calls from staffers at the polls; all reported turnouts running twenty, thirty, fifty bodies ahead of Richard Murray’s predictions. At 1:30 the storm broke in the east and the calls changed: it was flooding in La Porte (groans); Clear Lake City was underwater (cheers). Murray called at 2:45 to report that his exit polls showed Andrews with 59 per cent.

By 3:30 it was raining hard all over the district. At Faubion headquarters the word from Southwest Houston was very bad. Burnette had planned to send block walkers out late to catch people after work, but the rain had intervened. Only seven precincts had been walked. Burnette stood staring angrily out a window. He wheeled with a fierce shrug of disgust and spat, “This rain is killing us.” But it wasn’t the rain, and he knew it. It was the turnout. For as evening fell with the rain, the polls were still crowded. And that, finally, did kill the Republicans, including Mike Faubion.

On Wednesday, the day after, Faubion was stoic, Tamara sweet and dazed. People were already asking him to run again in ’84, the candidate said, but it was too early to contemplate that. “We have to rebuild our empire first,” Tamara said, thinking perhaps of the nearly $50,000 the campaign owed the candidate—$50,000 he might well never see. Upstairs, Burnette emptied wastebaskets overflowing with soft-drink cans and fast-food wrappers. His man had lost 38 per cent to 60 per cent (the Libertarian and the Citizens party candidate had split the other 2 per cent), but he had no regrets. “I wouldn’t do anything differently,” he said. “I would only do more.” It was really Governor Clements’ fault, he said. Reagan had alienated the workingman, and Clements had only made things worse. He’d taken all the money, he’d let his organization run roughshod over lesser candidates, but most of all he’d driven away the white working classes. “Pasadena was having none of Mike Faubion,” Burnette said. “We just couldn’t get through.”

The Next Step

Basking in the rare glow of a genuine Houston autumn afternoon, Mike Andrews let his mind roam forward. How would he choose a staff, he wondered. Which committee assignments should he seek—Energy and Commerce? Appropriations? Public Works? Where could he best establish himself within the party, yet not be put to too stern a test of loyalty? How would the men who had helped put him in office deal with him now? In short, how did one go about this business of being a congressman?

He of all people had contemplated the potential influence of the position he had won, what it could mean to be not just a congressman from Houston but the congressman from Houston. He and his friends hoped that, believed that they were witnessing a great transfer of power in the city, and that they were among the inheritors of that power. The mantle had skipped a generation, they said; now the Bob Parkers and the Bill Wrights and the Vic Driscolls and the Dick Trabulsis would assume it as the Browns and the Mischers let it fall. And Andrews knew without their telling him that they were capable of dreaming far beyond anything they had yet accomplished.

He was still adjusting to the idea of being a congressman and already his tailor was addressing him jokingly as “Mr. President.” A few days after the election he visited the office of his former law firm, and as a crowd of young lawyers gathered round to congratulate him, one burst through good-naturedly with, “Okay, when are we going to run for the Senate? When are we going to run for president?” The congressman-elect laughed along with everyone else, but he shied away from the questioner. It would be political suicide, and he knows it, to entertain such speculation openly. Let those around him entertain it if they must—after all, it was the aura of possibility that hung so richly over his campaign that was his true achievement. And if in the dead of night the demon ambition comes to whisper in his ear, “What if? What if?” and sometimes he allows himself to listen, who can blame him? For this is the last, sweet, hidden secret of politics: that sometimes, most times, the triumph of hope over experience is an illusion . . . but not always.

- More About:

- Politics & Policy

- TM Classics

- Longreads

- Houston