This story is from Texas Monthly’s archives. We have left the text as it was originally published to maintain a clear historical record. Read more here about our archive digitization project.

It was Tuesday, May 29, 1979, the first working day following the Memorial Day weekend, and Judge John H. Wood, Jr., was ready to get on with his business.

You couldn’t live in San Antonio in those not-too-distant days without being aware of the alarming acceleration of violence and the rampant stampede of paranoia. There had been a rash of cop killings, and drug dealers were slaughtering one another with a vengeance not seen since Prohibition. Daily news reports exploited the mayhem. A sniper had turned the gaiety of Fiesta week into a bloodbath. A highly esteemed career narcotics agent named Sante Bario, arrested and held at $500,000 bond on a charge of bribery brought by one of his own sleazy informants, collapsed suddenly in the Bexar County Jail: attending physicians believed Bario had been poisoned, but the coroner reported that he had choked to death on a peanut butter sandwich. To Judge Wood, the most shocking crime of all was the attempted assassination the previous November of federal prosecutor James Kerr, a close friend. Congressman Henry B. Gonzalez, who made a speech to Congress on the subject of King Crime, thought the death of the narcotics agent and the attempt on Kerr’s life were connected, and so did a lot of other people. Wood had written a supportive letter to the congressman, expressing his “deep feelings of outrage” that anyone would presume to intimidate justice.

Wood blamed dope dealers for a major share of society’s problems. The judge had never forgotten what he called “my Mexican connection case,” in which several key witnesses were murdered. Recently, FBI reports had linked drug trafficking in San Antonio and El Paso to “high-level organized crime” and indicated that some big names would soon surface. Some had already surfaced, thanks to leaks from James Kerr’s racket-busting grand jury: Joe Bonanno, Raymond Patriarca, and Tony “the Ant” Spilotro, among others. The murder of flamboyant El Paso attorney Lee Chagra a month after the attempt on Kerr also raised the specter of Mafia involvement.

Lee Chagra had built much of his reputation defending dope dealers, but prosecutors and narcotics agents were convinced that Chagra himself was the brains behind a gigantic drug conspiracy. Grand juries had been investigating Chagra and members of his family since at least 1973, a secret that Judge Wood had inadvertently announced in open court in October 1977, creating a furor that still bubbled just below the surface of the ongoing investigation. The fact that federal prosecutors had never been able to pin anything on Lee Chagra was the source of considerable embarrassment to the government, which used every opportunity to link the name Chagra with organized crime. When an underworld figure named Michael Caruana appeared in El Paso shortly after Lee’s murder, the feds made it part of the court record. According to an FBI agent, Caruana was one of the top men in an organization headed by New England crime boss Raymond Patriarca. As it turned out, Lee Chagra was murdered by two soldiers from Fort Bliss who came to his office for the comparatively pedestrian purpose of robbing him. But in the spring of 1979 Chagra’s murder appeared to be one more mystery in an ominous chain of underworld affairs.

Nothing ever came of the Mafia scare. In fact, the only major indictment handed down by Kerr’s grand jury was the one charging Lee Chagra’s younger brother Jimmy with being a drug distributor. When Jimmy refused the government’s offer of a fifteen-year prison sentence in return for his cooperation, a superseding indictment was filed charging the El Paso high roller with continuing criminal enterprise, the so-called kingpin rap. That was as close as the feds would get to establishing a Mafia connection. “Organized crime, my eye!” Hank Washington, the crusty old chief of the Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA) in El Paso was heard to exclaim. “It looks more like disorganized crime to me.”

None of the federal judges or prosecutors in the Western Texas District had much experience with the crime of continuing criminal enterprise—it had never been tried in that district, and only a few cases had been tried anywhere. Still, the charges against Jimmy carried a possible penalty of life without parole, and Wood looked forward to hearing them. They didn’t call him Maximum John for nothing.

Wood’s indiscreet expressions of opinion, his harsh sentences, and his blatantly unfair rulings against defendants charged with drug-related crimes were subjects of substantial controversy, not merely among Wood’s enemies but among his friends too. Former chief prosecutor John Pinckney had warned Wood several times that his pro-prosecution posture was damaging the system. “The system depends not only on fair play but on the appearance of fair play,” Pinckney said. “A judge can’t associate socially with the prosecution [the way Wood did with Kerr] and still call them correctly.”

Maximum John hardly ever gave probation and had once sentenced a heroin dealer to 35 years for contempt of court. But it wasn’t just the harsh sentences that upset other judges and prosecutors. “It had more to do with demeanor than substance,” one judge said. “I may sentence somebody to thirty years, but I try to explain to them why I did it. If anything, I sympathize with them rather than chastise them, because thirty years is thirty years any way you dish it out. But Judge Wood seemed to sentence with relish.” No judge in the district suffered more reversals than Wood, but the risk of reversal didn’t seem to bother him. He agreed with his mentor, the late Judge Ernest Guinn, who used to say, “I can sentence them faster than they can reverse them.”

Pinckney and others also feared for the judge’s safety, more so since the attempt on Kerr. For a while, teams of U.S. marshals guarded all the judges in the district and some of the prosecutors, but recently Wood had waived this precaution. “If they’re going to kill me, they’re going to kill me,” he told a law clerk. He told a fishing companion, “I must be making a dent in their ranks, or they wouldn’t be so dead set on trying to do away with me.”

When the judge walked out of his townhouse that morning and prepared to drive to the federal courthouse on the HemisFair grounds, he looked rested and ready. He and his wife, Kathryn, had just returned from a holiday at their Gulf Coast resort home in Key Allegro, near Rockport. Wood had once played on the University of Texas tennis team, and at 63 he could still wear down men half his age. As usual, his docket was jammed: prosecutors went out of their way to arrange for Wood to hear important drug cases. They had done that with Jimmy Chagra’s trial too. It had originally been set to begin that day, but the judge had granted a postponement until August.

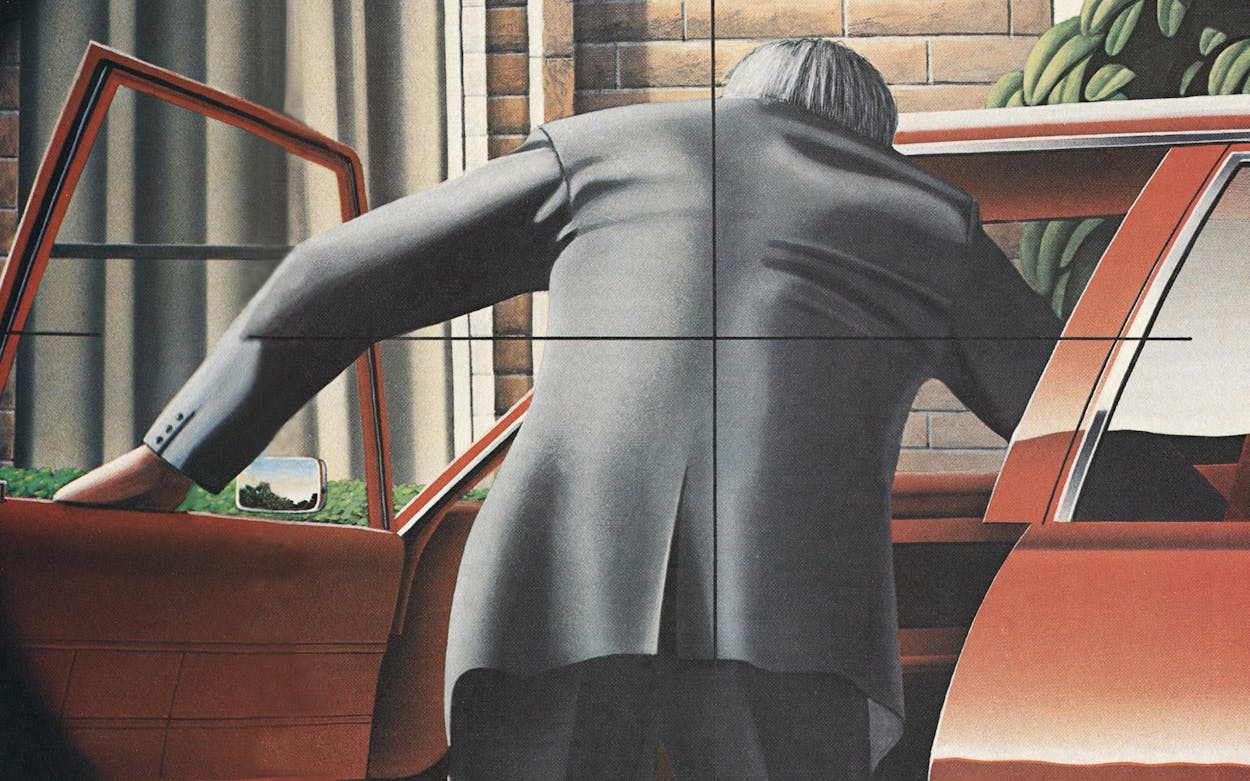

Directly across the driveway from Wood’s townhouse, the family of U.S. judge Adrian Spears, chief judge of the district and Wood’s close friend, watched from their breakfast room window as Wood walked briskly to the sedan parked in front of his townhouse. He frequently drove his station wagon, but this morning it had a flat tire. He slipped behind the wheel and tried to start the sedan. Nothing happened. The motor was dead.

James Spears, one of the sons of the chief judge, watched Wood get out of the car and lean across the front seat to retrieve his briefcase. Then he heard a noise. “It sounded like a backfire,” he said. “A loud backfire.”

His sister Carol remembered: “I saw [Wood] step backward. I didn’t know he was shot. There was no blood or anything. Then he sort of twisted around and fell on his back.”

James Spears telephoned the police emergency number, then ran downstairs and across the driveway to where Wood lay, next to the open door of the sedan. “There was no one in the area, no one at all,” he said. “No moving cars, no people, no more noise after the shot.”

Wood’s eyes were open, but he didn’t speak or move. Spears couldn’t see any blood, nor could he see the small entrance wound of the high-velocity rifle bullet that had slammed into Wood’s lower back and shattered into dozens of fragments. He pressed a finger against an artery in the judge’s neck, but there was no apparent pulse.

John Wood was already dead.

The killer had disappeared into the heavy flow of morning traffic along Broadway. It had been a clean, perfect shot. He’d watched Wood quiver for a fraction of a second, then drop in his tracks.

Within minutes, one of the most intensive and costly investigations in history was under way.

$100,000 Down and Human Collateral

Jimmy Chagra would have had to wear a sack over his head if word had gotten out, but in the summer of 1977 he was working as a glorified mule in a smuggling operation headed by Southwest dope czar Henry Wallace. These were hard times for Chagra. He’d scored big two years earlier when he and some friends first made their Colombian connection and successfully landed a freighterload of marijuana in an isolated cove near Boston. The following summer, Jimmy and his brother Lee blew millions in the casinos of Las Vegas. But Jimmy’s losing streak didn’t stop in Vegas. Shortly after Christmas, 1976, drug agents in Ardmore, Oklahoma, seized a DC-4 with 17,000 pounds of top-grade Colombian marijuana on board. None of the authorities were able to pin that one on Jimmy, and the ten smugglers caught in the raid were acquitted, thanks to some fancy legal work by Lee, but the material loss was a major setback. When a DC-6 crashed on takeoff from an improvised field near Santa Marta, Colombia, the setback escalated into disaster. Then a third aircraft, a Learjet that Jimmy chartered from a firm in Las Vegas in an abortive effort to rescue a crew member who had been badly burned in the DC-6 crash, was seized by Colombian authorities. The crew member died after the Colombians refused to allow two paramedics who had accompanied Chagra to administer treatment. Jimmy and some others were arrested and held in Colombia for several weeks. No charges were filed, but the loss of the aircraft and the cargo, combined with the massive publicity, momentarily paralyzed Jimmy’s budding career as a dope entrepreneur. That was when he went to work for Henry Wallace.

Wallace operated out of Berino, New Mexico, a tiny farming community in the Upper Rio Grande Valley, just across the state line from El Paso. Jimmy had known Wallace for more than a year, and they had become good friends —gambling, doping, shooting pool, comparing notes. Jimmy swallowed considerable quantities of pride when he had to ask the Fat Man, as Wallace was called, for a job.

Wallace was a smuggler’s smuggler. He had his own unlimited source of marijuana, supplied by a commander of the federales in Mexico. Wallace subcontracted with a number of experienced pilots, including Marty Houltin, commander of a notorious clan of New Mexico smugglers known as the Columbus Air Force, and Jim French, an aging scammer who lived in semiretirement on an old smugglers’ ranch in the Gila Wilderness. Dallas attorney Billy Ravkind, who represented French, once described Wallace’s many-tiered operation in this manner: “The left hand didn’t know what the right hand was doing. In fact, the left hand didn’t know what the left hand was doing. This finger didn’t know what that finger was doing.” Richard Young, a San Francisco musician who worked for Wallace in the winter of 1977 and later became a full partner in other scams, recalled his first very narrow glimpse of the big picture. Young was paid $2000 a trip to truck marijuana from New Mexico to Indiana. He never saw the people who delivered the truck in New Mexico, and he never saw the people who received it in Indiana. His job was to drive, period. And just in case he got any bright ideas, a “chase car” followed him all the way.

In the summer of 1977 Jimmy’s friendship with Wallace was severely strained when Wallace was unable to pay Jimmy $150,000 for his part in a marijuana shipment out of Mexico. Wallace testified that he called a summit meeting at the home of one Leslie Harris in the Upper Valley to discuss what had happened to the missing funds. It was a decidedly acrimonious meeting: almost everyone carried a gun, and at one point two former Bandidos who worked for Jimmy Chagra threatened to pour gasoline over Leslie Harris’s dog and light a match. Acting as peacemaker, Wallace suggested privately to Chagra that the two of them form a new partnership. Wallace needed Chagra’s connections in Colombia—it was becoming increasingly difficult to peddle low-quality Mexican weed, which partly accounted for the missing money—and Chagra needed a grubstake. This was Wallace’s plan: they would first smuggle in fifty pounds of cocaine, then use the profits to smuggle a freighterload of prime Santa Marta Gold, the smoke of discriminating weedheads, who would pay four or five times the price of Mexican grass. Chagra agreed, and they sealed the partnership with a snort of coke.

Chagra was dead broke, but Wallace was more than willing to carry his friend. Wallace borrowed $15,000 seed money from Richard Young, promising Young a piece of the deal, and another $60,000 from friends in Florida. At one meeting Wallace fronted Chagra six ounces of cocaine, and at another he gave Chagra $50,000 of his own money. Jimmy was also able to borrow money from his family, telling them the publicity made it impossible to continue enduring life in El Paso. He said he wanted to move to Canada and find a new life, but that was a lie. He intended to move to Fort Lauderdale, where he would set up an offloading operation for the eventual shipment of marijuana. He knew a man who had several large fishing boats suitable for the task.

The immediate problem was finding a pilot (Jimmy didn’t trust his own pilot after the crash in Colombia) and an airplane of sufficient range to fly from Florida to Colombia and return with the cocaine. Wallace suggested Jim French, but Chagra hesitated: the Frenchman hated Jimmy’s guts because Jimmy had cheated him in several earlier deals. That didn’t worry Wallace, who lured French out of retirement by promising him a one-third partnership. Of course, he didn’t tell French that Jimmy Chagra was also a partner, just as he failed to mention to Jimmy that Richard Young was part of the deal.

Wallace also contacted an El Paso travel agent named Dudley Connell, hoping to borrow money. Connell introduced him to a friend in Denver, Paul Taylor. Neither Connell nor Taylor came up with money, but they agreed to help sell the cocaine and put the profits back into the boatload of marijuana.

By October, Chagra and all the other smugglers were in place and ready to execute the scam. French and Young had delivered a newly purchased Aerocommander to Florida, and Wallace had gone to Santa Marta to arrange to have the cocaine fronted. Now came the first major hitch. Chagra’s longtime supplier refused additional credit: he had never been paid for the marijuana confiscated in Ardmore or the load burned in the plane crash. The resourceful Wallace found another supplier, Raul Ruíz, who agreed to front six kilos (they had planned on fifty) at a price six times higher than expected. Wallace would be held hostage pending payment.

It was late October before they got a break in the weather. French, Chagra, and Young headed for Colombia in the Aerocommander. Four hours into the flight they developed engine trouble over the Windward Passage and were forced into an emergency landing at Great Inagua. It was another two weeks before Chagra located a new airplane and the six kilos were finally delivered to Florida.

The cocaine turned out to be of poor quality and none of the money ever found its way back to Colombia. Connell and Taylor took a kilo on consignment but never bothered to pay. Again, Wallace saved the day. He convinced the Colombians that the money would be forthcoming and worked a deal whereby a second supplier, José Barros, agreed to front 30,000 pounds of marijuana and provide a ship if Chagra would make a down payment of $100,000, which he did. Once more, Wallace remained as human collateral, but Chagra arranged for Wallace’s wife and young daughter to join him in Santa Marta.

Wallace didn’t know it, but Chagra was working a side deal with huge profit potential. While waiting for their shipload, Chagra began making daily reconnaissance flights over the shallows of the Great Bahama Bank, looking for ships that had missed their rendezvous points and were anchored there like sitting ducks. This was extremely dangerous business, elbowing in, as it were, on someone else’s operation, but Jimmy reasoned—or so he said—that once the marijuana was off-loaded and headed for market, he could locate the real owners and work out the financial details.

Although Jimmy hadn’t anticipated this piece of good fortune, he had arrived in Florida at the crest of the marijuana boom. By late 1977 marijuana trafficking was far and away Florida’s leading industry. In Dade County alone, marijuana generated an estimated $7 billion, easily surpassing the $4.1 billion reported from tourism. Colombia’s gross income from marijuana and cocaine was $8 billion, five times the national budget; two million tons were shipped each week to the United States, most of it undetected. The 35-ton coastal or island freighter had replaced the airplane as the preferred conveyance. In most cases, the Colombians were willing to front both the dope and the ship. A government report estimated that at least 160 coastal freighters made regular dope runs from Colombia.

American authorities were losing the war, and they knew it. The ocean was simply too big, as were the profits and the variety of otherwise respectable citizens willing to risk sharing them.

Hovering Vessels

Two days before Christmas, 1977, as Wallace supervised the loading of a coastal freighter called the Dona Petra in a cove on La Guajira Peninsula, Jimmy Chagra was busy freelancing the cargo of two other ships. He had spotted the Miss Connie and the Eco Pesca IV, two freighters of questionable registration, anchored in the shallows off Orange Cay. The pilot of a Coast Guard spotter plane had noticed the same two ships. They were anchored thirty miles from the nearest shipping lane, a dead giveaway that they carried illicit cargo.

Chagra’s off-loading crews had barely departed with 24,000 pounds when the crews of two Coast Guard cutters boarded the so-called stateless vessels (no proof of registration) and seized the remaining 106,000 pounds. An old Prohibition statute that refers to “hovering vessels” allowed authorities to seize illegal cargo on the high seas and tow the offending ships to port, but it did not provide for the arrest of the crews. They were shipped home at U.S. government expense, and the freighters were sold at auction, frequently to brokers representing the original owners. Of course, the captains of the Miss Connie and the Eco Pesca IV named Jimmy Chagra as their contact.

Wallace was furious when he learned that his partner had branched out into the freelance business. He considered it unprofessional, especially since Chagra didn’t seem willing to cut him in. Wallace flew to Florida on Christmas Day with their cocaine supplier, Raul Ruíz, who was anxious to settle up. Chagra stalled Ruíz with a payment of $40,000 and a promise that Wallace would deliver the remainder of the money within a week, which he did, along with several hundred thousand dollars’ worth of radio and navigational equipment for the next freighter.

Four days after Christmas the Coast Guard cutter Cape Shoalwater spotted the Doña Petra anchored 55 miles east of Miami. By New Year’s Day, the Doña Petra, still fully loaded, was moored at the U.S. Customs Service dock in Miami.

By then Wallace and the other conspirators had had a bellyful of Jimmy Chagra. No one, not even the Colombians, had been paid. Chagra casually dismissed the loss of the Doña Petra: after all, it was Wallace who had made the deal. Chagra had already found a new supplier in Miami, another Colombian, named Theodoro, and he demonstrated little interest in settling old debts. Chagra’s greed and resounding stupidity had compromised the entire scam.

Wallace formulated his own private plan to cut Chagra out of the operation. First he flew to El Paso with three kilos of cocaine and $100,000. He gave the money to the Colombians as partial payment for the loss of the Doña Petra and used most of the coke himself. In late February, Wallace called a secret meeting in New Orleans, inviting Jim French, Richard Young, and most of the others, but pointedly neglecting to tell Jimmy Chagra, who was to be the main topic of conversation.

The meeting was convened in a suite at the Hilton Inn near the New Orleans International Airport. Wallace, a prodigious user of alcohol and cocaine, provided the refreshments and did most of the talking. Richard Young recalled: “Everyone there was mad at Chagra. We had used him in Florida because we had no one else to offload the boats. That was his only job, and he’d screwed it up royally.” Wallace told the others that the next shipment would arrive in New Orleans, not Florida as Jimmy Chagra anticipated. Chagra was out of the deal, period. Nobody objected.

Wallace had already given Young money to set up their New Orleans operation, and he still had $114,000 in his pocket. Drunk on power, and on assorted chemicals, he staggered across the Hilton parking lot to his rental car, which he proceeded to ram into the side of the airport limousine. Wallace was attempting to buy the limo when the cops arrived. That was the beginning of the end of the conspiracy.

The police turned Wallace over to the DEA. Agents found only a trace of cocaine, but the $114,000 and his reputation as a major cocaine dealer were taken as evidence that he wasn’t in town for Mardi Gras. During interrogation, Wallace admitted that he knew Jimmy Chagra and Jim French and agreed to cooperate with the DEA if the agents would return his $114,000.

Wallace was allowed to go back to Florida, where he was shocked to discover that the captain had missed signals and was about to land the cargo in Florida, as originally planned. Though Wallace had agreed to cooperate with the DEA, he had neglected to mention this shipment of marijuana, and by mid-March the weed was on its way to market. Instead, Wallace told the agents that a Colombian named Raul Ruíz was in Miami: Wallace still owed Ruíz more than $2 million and perhaps saw this as an opportunity to settle the debt. As far as Jimmy Chagra knew, the operation worked perfectly.

The House in Las Vegas

Jimmy had married his girlfriend, Liz Nichols, in January, and by summer he was ready to fold the Florida headquarters. He bought a twelve-room house in Las Vegas, and while it was being remodeled he and his bride quartered in the Sinatra Suite at Caesar’s Palace. The suite and everything that went with it was on the house. Jimmy was a “preferred” customer of the casino, and over the next few months he signed markers worth several million dollars. Meanwhile, the money from the dope operation continued to flow back to his dealers in Florida. Jimmy sent chartered jets to retrieve it.

While Jimmy was living a lifestyle that would have shamed King Farouk, almost every other participant in the conspiracy was getting busted. Richard Young tumbled a day after Easter, when his van, loaded with marijuana, broke down in Ocala, Florida; he happened to take it for repairs to a garage frequented by the highway patrol. Connell and Taylor were popped in unrelated drug busts. In June Wallace was busted again, this time in Denver. With the exception of Jim French, every major member of the gang was talking to the feds.

Back in El Paso, Lee and the youngest Chagra brother, Joe—and nearly every other lawyer in town—were hearing rumors that Jimmy was about to be indicted. Jimmy was so arrogant and cocksure that he didn’t really believe it, and Lee had his own problems. He had repeatedly lost clashes with Judge Wood and with prosecutor James Kerr. Shortly after Wood’s blundering announcement that Lee was an ongoing target of the grand jury, Lee had a disastrous fling in Las Vegas, losing almost half a million dollars, most of which he couldn’t pay. Jimmy humiliated Lee by paying off the debt, then announcing to the bosses at Caesar’s Palace that the next time his big brother came to town, Jimmy wanted him treated like a goddam king. After that Lee refused to set foot in Vegas.

During the remodeling of Jimmy’s house, Joe and his wife, Patty, visited several times. Joe had finally convinced Jimmy that the threat of his indictment was real and should be regarded as extremely serious business, particularly if the case ended up in Judge Wood’s court. Joe speculated that Jimmy would have less than a fifty-fifty chance in Wood’s court, regardless of the particulars. Months earlier, in Florida, Jimmy had heard his brothers talk about the tyranny of Wood and Kerr. Lee had gone up before some mean judges and spiteful prosecutors before—he’d been doing it for years—but until recently he’d never taken it personally. He’d never hated them, or anybody else. That wasn’t Lee’s style. No one had ever seen Lee in such a state as he was in now, but few people really blamed him. “The sonofabitches are killing me, literally killing me,” Lee had said one night in Florida.

When Jimmy wasn’t working the tables at the casinos, he was gambling in private games with other Las Vegas regulars. Jimmy fancied himself a good and clever golfer, a real hustler, and this fantasy cost him millions in the autumn of 1978. Gamblers from Boston to Florida to Hollywood were talking about Jimmy Chagra in tones normally reserved for particularly memorable pieces of cheesecake. A Hollywood producer told friends that he had taken four hundred grand off Jimmy in a golf match. “The ignorant bastard was trying to hustle me,” the producer said.

Money didn’t seem to matter that much to Jimmy, as long as he had it. He loved to flaunt it. He instructed Liz always to carry at least $10,000 in her purse, and she made a point of doing so: she knew better than to cross Jimmy. Joe remembered the gigantic walk-in safe that Jimmy had installed in his new home—it was usually overflowing with bundles of cash. From the summer of 1978, when Jimmy left Fort Lauderdale and moved to Vegas, until shortly after Lee’s murder in December of that year, Jimmy spent a fortune. Maybe $20 million, maybe more.

The renovation of the new house cost nearly $1 million, a stiff price for this bizarre monument. Jimmy’s primary concern was to make the house larger and better than the one Lee had built for himself in El Paso. He was especially proud of the master bedroom. It was as large as three normal rooms, and except for the lavender drapes, which Liz selected, everything in the room was mirrors. Mirrored walls, mirrored ceiling, mirrored floor, even mirrored furniture. It turned one man into an infinite number of himself and made two look like a mob. The main piece of furniture was a canopied four-poster, the width of two king-size mattresses, made of mirrors and polished chrome. Concealed in the headboard was a console of buttons and switches controlling an obscene number of electronic gadgets, including a six-foot TV screen that appeared from behind a panel of mirrors, a fireplace that burned artificial wood with artificial fire, and a saunalike environmental chamber that could simulate rain, Baja sun, jungle steam, spring showers, or Chinook wind. Jimmy’s dream was one day to watch Lee’s expression as he was introduced to this room. But Lee died without seeing it.

Lee’s murder stunned everyone, but it nearly drove Jimmy crazy. First he blubbered like a baby, then he got a gun and stalked around the room, waving it wildly. “He wanted to kill someone, anyone,” recalled Patsy Chagra, their sister. Jimmy believed the murder had been committed by DEA agents acting under orders from Kerr and Wood. He especially blamed the judge. “He destroyed Lee,” Jimmy said. “He ruined him.” Like many others in the law enforcement establishment, Wood believed that Lee was the kingpin smuggler. Jimmy alone knew the terrible irony: Lee had never done a drug deal in his life. But he had faded Jimmy’s heat for years. Lee had aided and abetted some of convicted smuggler Jack Stricklin’s deals and had set up some dummy corporations for Jimmy’s Florida scam too, but he had never come close to doing what the government believed justified those years of harassment—he’d never masterminded a dope deal. That was Jimmy’s specialty, and in some perverse way the publicity that had ruined Lee had also damaged Jimmy by depriving him of the recognition he wanted.

A few weeks after Lee’s murder Jimmy was indicted by a grand jury in Midland, the only place in the district where he was certain to be tried by John Wood. The prosecution claimed that one of Jimmy’s planes had once flown over Midland, a legal ploy that the defense was powerless to prevent. The trial was set for May 29. Wood first set bond at $1 million, though he later reduced it to $400,000, and Jimmy returned to Las Vegas to wait. He was convinced that he would lose in Wood’s court, but he was also convinced that the judge would make a reversible error.

In early May, Jimmy was a prominent figure on the fringes of the World Championship of Poker at Binion’s Horseshoe Casino. That was when he was introduced to Charles Harrelson, a convicted hit man. He talked with Harrelson for less than a quarter of an hour, but that was enough time to plan an assassination. Jimmy wanted Wood to pay for what he imagined Wood had done to Lee. Jimmy assumed that he would go to jail at the conclusion of the trial, and he calculated that the hit should be scheduled shortly after the sentencing, when he would have a perfect alibi.

Jimmy was playing cards on May 29 when he heard that Wood was dead. “I nearly puked,” he said. “It wasn’t supposed to be like that. It was supposed to be after the trial.”

After that short conversation in Vegas, Jimmy didn’t see Harrelson again. Jimmy didn’t know for sure who had killed Wood.

“Are You the Boss? Is Your Name Jimmy Chagra?”

Judge William S. Sessions sat ramrod straight, impervious to the August heat that wilted everyone else in the Austin courtroom. A tall, thin-lipped, humorless man with the bearing of a nineteenth-century British headmaster, Sessions seemed so stiff and correct that he might have been wearing a whalebone corset under his black robe. More likely, he was wearing a flak jacket. Most of the judges and prosecutors in the district adopted that as a standard item of clothing after Wood was gunned down.

Sessions, who had been a federal prosecutor before President Ford appointed him to the bench in 1974, was next in line to become chief judge (an honor that would have gone to Wood) and was probably the best-qualified judge to hear the Chagra case. He had never had any dealings with any of the Chagra family, nor did he have especially close personal ties to Judge Wood.

Under the best circumstances—and these were just about the worst—Jimmy Chagra’s trial promised to be delicate and difficult. The three-month-old investigation into the Wood murder (said to be the most intensive since the assassination of John Kennedy); the media attention to the Chagra family, dope smuggling, and organized crime; the elaborate courtroom security; and the FBI’s description of Judge Wood’s murder as “the crime of the century”—all these things overshadowed the trial. Even without the gusher of publicity, there were intrinsic legal problems. No one seemed sure how to proceed under the kingpin law. The statute itself was hopelessly vague. There seemed to be two burdens on the government: (1) to prove that the defendant was the boss of the smuggling ring, as opposed to merely another hand, and (2) to demonstrate that he made a “substantial” amount of money from drug trafficking, as opposed, say, to gambling, which Chagra listed as his profession. To support its contention, the government had granted immunity to almost all of the other members of the conspiracy.

The case for the defense rested on the jury’s believing that Jimmy Chagra was a “two-fisted professional gambler” victimized by the “purchased testimony of government witnesses.” Chagra maintained that the feds had an ongoing vendetta against his family. Lee was the man they had really wanted; Jimmy was just a consolation prize. One defense witness was U.S. attorney Jamie Boyd, who had once testified that DEA agents lie, tamper with evidence, and commit other crimes in pursuit of their trade. Jamie said these things in defense of a friend who had been a customs agent before being mauled in an interagency political battle with the DEA, but having said them, he was on record.

The fact that he was on call as a defense witness precluded Jamie’s active participation in the prosecution, about which he was secretly relieved. He preferred to orchestrate from the wings. No matter how it looked from the outside, this was Jamie Boyd’s show. He had been waiting a long time to poleax a Chagra, and getting a kingpin in the deal was a bonus without parallel. For days now, Jamie had personally prepped his star witness, Henry Wallace. He’d actually come to enjoy Henry’s hardscrabble style and honest flair for crime. Jamie’s wife, Suzy, tells the story of the time they were all driving around Midland during Jimmy Chagra’s bond hearing, how Henry put his arm around a DEA agent, passed the bottle, and confessed that he might learn to like it here on the other side. When Henry started beguiling the jury with his tales of life, in the dope trade, the jury would understand what Jamie Boyd understood: that whatever Henry had done, he wasn’t as bad as Jimmy Chagra.

When the trial started on August 1, Henry Wallace set the stage for everything the prosecution hoped to prove. Henry was half Mexican, half Irish, a big teddy bear with a singsong Frito Bandito voice, and as he talked of tons of dope and millions of dollars and how Jimmy Chagra, the boss, had cheated them all, the jury hung on every word. Jimmy smiled and sometimes laughed at Wallace’s testimony. Judge Sessions had to warn the defendant several times that these proceedings were in no way humorous.

Wallace told the jury that he had first met the defendant, Jamiel Alexander Chagra, in the summer of 1977 at the home of Leslie Harris, where a group of smugglers and dealers had gathered to discuss what had happened to the money from a large shipment of marijuana.

Carl Pierce, the prosecutor Jamie Boyd had tapped to lead the government’s case, wasted no time in establishing the thesis.

PIERCE: When you first met Mr. Chagra . . . what did you say to him?

WALLACE: My first words to Mr. Chagra were, “Are you the boss? Is your name Jimmy Chagra?”

PIERCE: What did he reply?

WALLACE: “Yes.”

Bribes and Lies

Like ducks in a line, the co-conspirators told their sordid stories and named Jimmy Chagra as the boss. Several witnesses got their stories crossed, but the weight of the testimony had an obvious effect on the jurors, none of whom had ever before heard the confessions of big-time dope traffickers.

All during the seven days that the government took to present its case, something kept bothering Joe Chagra. He had agreed to play second chair to Oscar Goodman, the high-priced Las Vegas lawyer whom Jimmy had personally selected to head up his defense. Goodman, who had made his reputation by defending some of the legendary names in organized crime (among them Meyer Lansky), was a good lawyer but a poor choice in this particular case. His fast-paced Philadelphia delivery failed to elicit much sympathy from a down-home Central Texas jury made up mostly of current or former government workers.

While Goodman was cross-examining Wallace, Joe Chagra kept wondering about Jim French. Where was French? Why hadn’t he been indicted with the others? The defense lawyers had considered calling French as their own witness but decided it was too risky. As it turned out, this was one of their fatal mistakes.

It was almost exactly one year later, during his own smuggling trial in August 1980, that French (corroborated by Richard Young) made it clear that Henry Wallace was the boss. “It was basically Wallace’s deal,” the Frenchman said. “He got the money, put the deal together, and went to Colombia. The only reason Jimmy was even there was because he knew some people to off-load the marijuana. Wallace definitely called the shots—not Jimmy. Nobody in their right mind would work for Chagra. He was a liar and a cheat and a thief. Nobody in our business trusted him.” Young testified that he never regarded Chagra as anything except a flunky. Why hadn’t Young said this at Jimmy’s trial? “Nobody ever asked me,” he replied.

The defense’s second big mistake was not properly analyzing its own case. Regardless of the government’s evidence, it was still possible to take the low road: it was still possible to maintain that while the defendant had smuggled some marijuana for Henry Wallace, he had never been involved in the more serious crime of cocaine smuggling. The DEA had conceded that “not one iota of cocaine” had been traced to Jimmy Chagra. The problem was, Jimmy seemed to want it both ways: he wanted to be found not guilty, but he also wanted people to believe that he was the boss. He insisted that his lawyers continue to pound at the theme that the real criminals were the unscrupulous agents of the DEA and their hired stooges, the co-conspirators. Against the better judgment of his lawyers, Jimmy Chagra took the witness stand.

Jimmy’s testimony was a disaster. Even under the friendly guidance of Oscar Goodman, he came across as arrogant and petulant, and when the prosecution started working him over, his responses were so bellicose that even his friends in the gallery felt a sense of resentment. Jimmy denied that he had ever been involved in drug smuggling. He had made all that money gambling. He didn’t even know that his friend Henry Wallace was a drug smuggler. He thought Wallace was a farmer. He barely knew French and thought he, too, was in farming. He’d met Richard Young once, and he’d never met any of the others. He couldn’t explain government exhibits demonstrating hundreds of telephone calls from his home in Fort Lauderdale to the homes of the other conspirators—maybe someone had used his phone. As for the 34 separate billings from his phone to the Republic of Colombia, Chagra told the jury that he had a number of “adopted children” living there. No, he couldn’t remember any of their names. But he remembered something else. He remembered that during the time Wallace was in Colombia (doing what, he didn’t know), Wallace’s wife, Betty, stayed at the Fort Lauderdale Hilton. “She came to my house every day . . . she used my phone because she said they were broke,” Jimmy said, leaving the jury to speculate how a woman with no money could live for two and a half months in a Florida resort hotel. Chagra didn’t realize that the government already had passport, hotel, and airline records proving that Betty Wallace had stayed in Florida exactly three days. Or that Betty herself was ready to testify that she barely knew Jimmy Chagra and had never set foot in his home.

There was one more major surprise in the trial. Earlier in the week Jimmy had accidentally run across Henry Wallace in the bar of an Austin hotel, and there was an apparent attempt at extortion, or bribery, depending on which story you believe. According to Chagra, Wallace offered to change his testimony—and get Richard Young to change his—for $300,000. Wallace gave him no choice, Jimmy told the jury. If he refused, Wallace would carry through a DEA plot that would frame Jimmy for the murder of John Wood. (This was one of the few times Wood’s name was mentioned in the jury’s presence.) Recalled to the stand, Wallace confirmed the accidental meeting but said the bribery attempt was Chagra’s idea. He denied the part about the DEA plot but admitted taking $1000, which he turned over to the prosecution.

The jury took less than two hours to find Chagra guilty of continuing criminal enterprise and everything else in the indictment. Sessions released Chagra on $400,000 bond and set September 5 as the date for sentencing. But Chagra had no intention of being sentenced. A week after the trial he jumped bond and disappeared.

Six months later, in February 1980, the FBI arrested Jimmy outside a cheap Las Vegas motel. The fugitive was unarmed and carried $180,000 hidden in a box of diapers. It wasn’t clear why Jimmy had come back to Vegas, though some speculated that he had returned to have plastic surgery done by a doctor who was famous for changing the identity of underworld characters. The tip leading to Chagra’s arrest came from a casino waiter who had been sent out to buy some wigs for Jimmy and his wife.

Judge Sessions sentenced Chagra to thirty years without parole. In April 1980 he entered the U.S. Penitentiary at Leavenworth.

Sluggo and Mr. Bill

It was like watching time-lapse photography, the way Joe Chagra had aged. Two years ago he had looked like a kid auditioning for West Side Story, heavy on bluff and uncertainty, charged with supermachismo as he bobbed behind his mirrored sunglasses, a cigarette dangling from his lips—and yet so obviously fresh and clean that he squeaked. Now that Lee was dead and Jimmy faced the prospect of dying in prison, Joe was the patron of the family, like it or not. His hair was longer, and carefully styled. His face showed signs of weathering, and he frequently used cocaine. He was still painfully handsome: you couldn’t look at Joe without thinking of Al Pacino in The Godfather. But he had learned to express himself, to drop the act and come down hard if he had to.

Joe’s whole life seemed unencumbered by choice; the stream of events that was the Chagra family legacy seemed to flow down and deposit its silt at his feet. He had wanted to be a doctor, not a lawyer. He had tried working his way through undergraduate school, and he worked so hard that his grades suffered. When he realized that he wouldn’t be admitted to medical school, he took Lee’s advice and followed his path. Right up until Lee’s death, Joe was always in his shadow. Lee always gave Joe the short end, and Joe took it because that’s the way it was in their family. Now he was in Jimmy’s shadow, doomed to follow another trail he had never intended.

It was all so unfair, so fraught with potential for disaster. Lou Esper, convicted of setting up Lee’s murder, was doing a measly fifteen years. Hardly a week passed that Joe didn’t get a letter or phone call from some con offering to “kill the guy who killed your brother.” It seemed to go with the territory. Now that Jimmy was a target in the Wood investigation, Joe had to screen vague offers from shadowy people claiming to have information about that crime. The government was showing early signs of panic. The investigation was stalled, and there were rumors that frequent quarrels were dividing Jamie Boyd and certain FBI agents.

By the spring of 1980, what had really happened in the Wood murder was becoming clearer to Joe. He remembered that day a month before Lee was killed, the day they heard about the attempt on James Kerr. “Lee and I looked at each other. Lee was pale as a ghost. I knew what was going through his mind, but neither of us said anything.” They had all talked about how the bastards ought to be wasted, Kerr and Wood. Joe had never dreamed it would happen, and he was certain Lee hadn’t either. Jimmy was another matter. Jimmy might have put a contract on Kerr just to prove to Lee that he could.

This was also the spring when Joe first met Charles Harrelson, the man who two years later would be indicted as the triggerman. They were introduced at the home of a mutual friend. Joe recognized the name Harrelson as that of one of the witnesses who had testified before Jamie Boyd’s grand jury investigating the assassination. A known gambler and hit man, Harrelson had apparently been cleared in the Wood murder. The thing about Harrelson that most interested Joe Chagra at the moment was Harrelson’s cocaine: he had an enormous supply. Joe was spending $100 a day, sometimes more, on his own habit.

In the weeks that followed, Joe Chagra and Charles Harrelson saw each other a number of times. Harrelson, who had been arrested a few months earlier in Houston on drug and gun charges, was using the alias Jo Robinson. Joe Chagra claims that at this time he agreed to act as Harrelson’s attorney.

Several weeks after their first meeting, Harrelson was hired as a bodyguard by Virginia Farah, widow of the cofounder of Farah Manufacturing. Virginia was Patty Chagra’s friend, and Joe drew up the contract of employment. This was a traumatic time in Virginia Farah’s life: her son, daughter-in-law, and granddaughter had been killed in an auto accident on Memorial Day, and she was also embroiled in a bitter lawsuit with her former brother-in-law, Willie Farah. Harrelson, or Jo Robinson, as she knew him, was a ruggedly handsome, enormously self-sufficient man of considerable charm. He obviously knew how to handle himself, and he was patient and attentive to Virginia. Several times that summer Harrelson invited Joe and Patty and their two children to the Farah home—he thought Virginia needed to be around children—and he enjoyed entertaining them with a dazzling array of card tricks he had mastered while spending 27 months in solitary at Leavenworth.

Harrelson was married to Jo Ann Starr, a former Las Vegas blackjack dealer who had known Lee. In fact, Lee once defended Jo Ann’s boyfriend, Peter Kay, on charges of killing for hire. Peter Kay and Harrelson were close friends. Harrelson told Joe some of what had taken place in Las Vegas in the weeks just before Wood’s murder. A team of Texas gamblers had worked a scam to take Jimmy for several million dollars. One Texan known by the code name Sluggo challenged Jimmy to a high-stakes golf game. Jimmy didn’t know it, but the gamblers had also given him a code name—Mr. Bill. Dressed as grounds keepers and using two-way radios, the gamblers arranged for all of Jimmy’s shots to end up behind trees, while Sluggo’s ball was habitually discovered a few feet from the pin. Jimmy dropped $580,000 that afternoon. Everyone in Vegas heard him bitching and moaning and complaining that his luck had never been so bad. When Jimmy asked for an opportunity to recoup his losses, the gamblers invited him to play cards, and then dice. Both games were rigged, of course.

About that same time Harrelson arrived in Las Vegas. He later told friends that he, too, had cheated Jimmy, though in a more menacing fashion. Harrelson offered to kill the man who had killed Jimmy’s brother, or to kill Judge Wood, whichever Jimmy preferred. He accepted the contract on the judge, though he told friends that he had no intention of fulfilling it. When Harrelson heard that Wood had been killed, he decided to claim credit—at least that was the story he was telling now. He sent his stepdaughter, Teresa Starr Jasper, to collect $250,000 from Liz Chagra.

As the attorney for both Jimmy and Harrelson, Joe had placed himself in the middle of what promised to be one of the bloodiest legal battles in history. To complicate matters, Harrelson had failed to show up for his trial in Houston and was now a fugitive.

Several times that summer Joe visited Jimmy at Leavenworth. It was only a question of time until the FBI caught Harrelson and put all the elements of the crime together. It occurred to Joe that he might become a target of the investigation too. He couldn’t help that. The time would come when the conspirators would be forced to cut their losses and make some kind of deal with the government. Joe’s strategy was to play for time, which depended on his ability to keep Jimmy and Harrelson from trying to work individual deals. Joe had to persuade them to hang together.

By late August, Harrelson, still hiding out, was losing touch with reality. He had started shooting cocaine, and he telephoned Joe one night, half off the wall because he had seen DEA agents perched in the trees outside Virginia Farah’s home. Harrelson disappeared for a few days, then called Joe from Houston with more wild stories about being chased by helicopters and about little men who bored holes through the bathroom wall. At Harrelson’s insistence, Joe taped this rambling, nearly incoherent monologue.

A few nights after that, Harrelson telephoned Joe from a motel on the east side of El Paso. That same night Joe received another phone call from one of Lee’s former clients, William Mallow, a fugitive who had escaped from a federal prison in Colorado. Mallow had warned Joe that he might try to escape, but Joe hadn’t believed him; Mallow had less than two years left to serve. But here he was in El Paso, staying at the same motel where Charles Harrelson was hiding. That night Joe introduced the two fugitives, and early the next morning he heard a news report that Mallow had been involved in a shootout with the El Paso police. When the feds discovered that Mallow and Harrelson had been registered at the same motel, and that Joe Chagra had been with both, they naturally perceived this to be another piece of the complex puzzle.

By early September Harrelson was in custody. He’d been driving Virginia Farah’s Corvette down I-10 in the desert somewhere east of Van Horn, shooting cocaine and seeing agents’ faces on highway signs. He stopped to inspect a rattling muffler, which he attempted to repair by shooting it with his .44 magnum. In his drug-induced dementia, he missed the muffler but managed to shoot out a rear tire. Motorists reported a crazed hitchhiker standing on the highway with a gun pointed at his head; when the police arrived they discovered Charles Harrelson. He held them off for six hours, pressing the muzzle of the .44 against his nose. Finally Virginia Farah was called to the scene, and she persuaded him to surrender. During the standoff, the police reported, Harrelson confessed to the murder of John Wood. He also confessed to killing John Kennedy.

Something Only the Killer Knew

These weren’t good times for U.S. attorney Jamie Boyd. The FBI’s year-long investigation of Wood’s murder had turned up nothing. Jamie was conducting his own investigation through the grand jury, but he believed that certain FBI agents were trying to undermine and discredit him. He thought they were jealous, and this reinforced his feeling that he was getting somewhere.

Jamie’s ace in the hole was a seedy little informant named Robert “Comanche” Riojas, who had been feeding bits and pieces of information to a certain FBI agent since a few days after the Wood murder. With the exception of this one agent, hardly anyone in the FBI believed anything Riojas said. Riojas faced charges in the murder of a Bexar County inmate and was obviously trying to make a deal. “Riojas was a bad joke, a certified maniac,” said Alan Brown, Riojas’s lawyer. “He was always stopping by my office, asking the secretary if she wanted anyone murdered. One day he’d have a story about murdering five Mafia figures in New York, and the next day he’d be talking about a shipment of machine guns. Nobody in his right mind believed Riojas.”

But little by little, Jamie Boyd was beginning to believe. He had agreed to place Riojas under witness protection. In time Jamie began to feel empathy with the little snitch, much as he had with Henry Wallace. Jamie’s wife, Suzy, baked Riojas a batch of cookies. Boyd couldn’t believe that Riojas was merely using him, although, as events proved, that’s what was happening. The FBI agent would ask Riojas about a certain name, and Riojas would grab the bait and invent a connection to Wood’s murder. He told of two meetings in which various underworld figures discussed killing Kerr and Wood. When the agent asked about some gamblers who had been friends with Jimmy Chagra, Riojas concocted the lie that these were the same men who had stalked Judge Wood for weeks. One of the gamblers frequented a resort motel just across the bay from the judge’s retreat at Key Allegro. The police checked motel records and learned that the hoods had in fact been there just before Wood was murdered. This was just one more coincidence, but Jamie didn’t know that. Some of Riojas’s stories were so wild and dangerous that they were instantly discounted, but one story almost caused the resignation of a high-ranking San Antonio police officer, and another delayed the confirmation of a federal judge.

When Harrelson was arrested in Van Horn in September, the prosecution took another look at him. Harrelson was a close friend of many of the gamblers and thugs Riojas had fingered. About that time, a Houston lawyer who was representing Harrelson made a halfhearted attempt to have his client confess to the Wood hit in return for a less-than-life sentence in a federal rather than a state prison. If Harrelson were tried by the State of Texas, he would face a death penalty. He was comfortable in federal prison—Percy Foreman once observed that he had never seen Harrelson so content as when he did his stretch at Leavenworth. Professional killers were accorded special status, and in no time Harrelson was running the yard. Harrelson had grown up in the shadow of the Texas prison unit at Lovelady. His father was a prison guard and his uncle was the warden. State prisons were mean and hard and unyielding, all the things Harrelson had been trying to escape all his life. The lawyer’s offer interested Jamie. He bucked it to Washington, but it was quickly rejected.

Then something else happened that made Boyd believe he was on the right track. Harrelson sent word to the U.S. attorney that he knew something only the killer knew: one of the tires on Wood’s station wagon was slashed just before the assassination.

The rambling interviews with Riojas didn’t constitute a neat scenario, but they did circumscribe a rough triangle connecting gamblers and hit men—what Jamie called the Dixie Mafia—to Charles Harrelson, then indirectly to an infamous desperado named Jerry Ray James. James couldn’t have taken part in the Wood killing—he was doing two life sentences at the New Mexico state prison at the time. But James was one of those cons who knew things. Compared with him, the gamblers and hit men described by Riojas were choirboys. Lawmen in the Southwest considered James the modern equivalent of Dillinger or Machinegun Kelly. Following the bloody Santa Fe prison riots, James was transferred to La Tuna federal prison, near El Paso, where FBI agents questioned him about Wood.

In June 1980, Jerry Ray James was transferred to Leavenworth, where he quickly became close friends with Jimmy Chagra. This was James’s fourth trip to Leavenworth: he was preceded by his reputation as a hardened, stir-wise con with a well-known hatred for snitches. James told Jimmy Chagra that during the Santa Fe riots he had broken into the comptroller’s safe and removed the prison’s list of informants, and that he had personally killed nine of them. That was a lie, but it had the desired effect. In a short time, Chagra was bragging about his own life of crime, starting with how he had had Judge John Wood wasted.

Beginning in October, the FBI taped hours of conversations between James and Chagra, coaching James between sessions on what questions to ask and what areas to cover. On a number of occasions James reminded Jimmy to be sure and tell his brother about their various schemes. At one point Joe Chagra received a call from a con in Leavenworth, warning him that Jerry Ray James was a snitch, but when Joe told Jimmy, he laughed at the notion and so did everyone who knew James.

The tapes of conversations between Jerry Ray James and Jimmy Chagra were used to persuade a federal judge in Kansas City to allow electronic surveillance of the entire Chagra family, including Jimmy’s three small children. That in turn led to court authorization to tape Charles Harrelson in the Harris County Jail.

Jamie Boyd was aware of all of this when he and his wife entertained an out-of-town visitor in early December. It was the first night since Wood’s murder that the Boyds had not been under the 24-hour protection of federal marshals, and the visitor was astonished at the degree of paranoia permeating the couple’s apartment. Jamie repeated his conviction that the entire Chagra family was mixed up in the assassination. Suzy apologized for the lack of security and said she hoped they wouldn’t all be murdered in their sleep. It was more than a year later when the visitor realized the source of the Boyds’ paranoia: the tapes revealed conversations in which Jimmy discussed with Joe his ideas for killing key witnesses, past and present.

The following day was Saturday, but Jamie kept an appointment at his office in what was now called the John H. Wood, Jr., Federal Courthouse. His meeting was with a high official from the Department of Justice who had come to inform the U.S. attorney that he was no longer in charge of the Wood investigation. Jamie knew that he had become a lame duck when Ronald Reagan was elected, but he figured he’d serve at least until the new administration took office. The firing came as a shock, but also as a relief.

Jamie told friends that Washington had taken him off the case because of a disagreement over the methods being used in the investigation. The deputy attorney general who had dreamed up Abscam wanted to use the same tactics to trap the Chagras and Harrelson. And Jamie didn’t. He thought that method was too risky. The use of government informants to trick suspects into confessions had been a valid tool of law enforcement as far back as the Jimmy Hoffa case, but bugging private conversations in which none of the parties was aware of or had given consent to surveillance was virgin territory, uncharted in the law. Worse yet, the government was tampering with the concept of attorney-client privilege. It was the kind of thing the feds had done in the heyday of Joe McCarthy and J. Edgar Hoover, but this was the eighties. Jamie feared the long, costly investigation would fall victim to the domino theory: one wrong move and the whole case would tumble.

But there was yet another reason that Washington was disenchanted with Jamie Boyd. The star of Jamie’s grand jury, Robert Riojas, had been completely discredited. The government had spent millions running down rabbit trails, and all there was to show for it was a tainted grand jury. It would be necessary to impanel an entirely new grand jury to hear the new government theory.

After that, Washington took no chances. Jamie was quietly removed from office and given his old job as U.S. magistrate, which would allow him to retire with full benefits. All aspects of the Wood investigation were taken over by the FBI. Even the prosecutors who would work with the new grand jury were moved from the courthouse to the FBI office—from prosecution to enforcement.

The Shredded Map

Patty Chagra knew that things were desperate, even if Joe didn’t. Joe hardly talked to anyone anymore. He snorted cocaine all night and slept all day, and even when his brain emerged from the shadows he seemed to be preoccupied with a morass he couldn’t articulate. His law practice was almost nonexistent, except for Harrelson and Jimmy. Patty had threatened to leave him.

“You’re more alone living with someone doing coke than if he’s not around at all,” she said. It wasn’t just the coke. Worse than the coke was its symptom—the easy money that had come from Jimmy’s smuggling operation. Patty remembered that even before Lee’s murder Joe would stay up all night counting money and snorting cocaine. She’d seen the effects of the money on the entire family. The jewelry, the expensive cars, the airs and pretenses. The Chagras used to be simple, decent people, a trifle eccentric, to be sure, but true to their code and ancestral traditions. Now they were the Lebanese Hillbillies.

By the fall of 1980 Patty was beginning to piece together the events of that summer, the visits to Virginia Farah’s, the whispers and secret conversations between her husband and Charles Harrelson. “It was a weird situation,” she said later. “Charles was so charming you couldn’t believe it. I asked him about stories that he was a hired killer, and he said he’d never killed anyone who didn’t need killing.”

Not long after Harrelson’s arrest in Van Horn, he wrote and asked Joe to visit him in the Harris County Jail. That was when Harrelson drew a map showing Joe where he had hidden the murder weapon. The map lacked detail: it showed a Stuckey’s near an exit on I-20 east of Dallas, then a large area that included Lake Ray Hubbard. If there really was a gun out there, a person would have to dig up a hundred square miles to find it. As soon as Joe returned to El Paso, he ran the map through the shredder in his office, but later, for some inexplicable reason, he drew it again from memory and locked it in his safe at home.

Harrelson had apparently told someone else about the gun too. The man told Joe that he had actually found the gun but had been too frightened to touch it. He also asked Joe to contribute money to Harrelson’s defense, even though Joe was already contributing his time as an attorney. Joe told Patty about this, and they agreed it sounded like a setup to trick him into looking for the gun. A few months later someone broke into Joe’s office. He believed it was the FBI looking for the map.

Joe’s bouts with depression and paranoia intensified each time he visited his brother at Leavenworth. He’d come home smashed, then sleep for two days. Once when Joe was supposed to be visiting Jimmy in prison, Patty called his motel in Kansas City and found him so loaded he could barely talk. The whole family was pressuring Joe—Mom Chagra; his sister, Patsy; Jimmy’s wife, Liz. They didn’t seem to understand what was happening to Joe, but they demanded to know why he couldn’t get Jimmy out of prison.

At first Joe told his wife about his talks with Jimmy, but after a while he was too depressed to discuss them. “You know Harrelson knocked off the judge,” Jimmy had said on one occasion. Joe didn’t really know that. He knew what Harrelson had told him, but he didn’t know what kind of game Harrelson was playing. Joe didn’t think Harrelson would rat on Jimmy, but Jimmy was sure of it. Jimmy would whine and complain and demand that Joe find a solution for the problem of Harrelson. “Off him!” Jimmy snapped at one point. Joe couldn’t believe Jimmy had said that. The gravity of the situation didn’t seem to register with Jimmy. It was getting so Joe couldn’t handle these talks. Jimmy was also talking about killing Henry Wallace. Jimmy’s inmate pal Jerry Ray James had a friend who would make Wallace “disappear” for a price. During one visit Jimmy asked Joe to deliver a message to Jack Stricklin, who owed Jimmy money. “If he don’t get that money up in two weeks I’m gonna off him. I’m not playing . . . I’ll have him f—in’ bumped off.” Joe promised to deliver the message.

Jimmy was willful and domineering with everyone, a bully and a braggart, but he was an absolute tyrant with his younger brother. Joe’s inclination had always been to placate Jimmy, to laugh it off and promise to support whatever ridiculous plan Jimmy might consider. If Jimmy had suggested blowing up the Pentagon, Joe would probably have agreed.

Jimmy was constantly talking about escape, not just to Joe but to a number of inmates at Leavenworth. During one conversation he told Joe about plans to use a helicopter. Once he’d broken out, Jimmy planned to move to the Orient and establish himself as a kingpin drug trafficker. Joe said he would help, though he didn’t believe Jimmy was serious. The problem was money. Jimmy accused Joe of squandering at least $400,000 of Jimmy’s dope profits. “You’re real happy playing with my money,” he said. “It’s like Monopoly money.” Joe denied squandering any of Jimmy’s money, but he believed it when Jimmy told him he had gone through a million dollars since being sent to jail. Jimmy had lost thousands betting on football games and gambling with other inmates.

During one prison conversation Jimmy said that if push came to shove, he would tell the FBI that Joe was in fact Mr. Big, the patrón of the family at the time of Wood’s murder. Joe didn’t believe Jimmy would actually do it, but Patty wondered. Jimmy had made a similar threat regarding their sister, Patsy. The mere suggestion illustrated that even behind bars Jimmy was dangerous.

Although Joe forgot most of the promises as quickly as he made them, there was one that held his attention. Jimmy had run across his Colombian supplier, Theodoro, in prison, and the two of them had hatched a plan for Jimmy to arrange to off-load a shipment of marijuana that was waiting off the coast of the Carolinas. Naturally, Jimmy would need Joe’s help. Though Joe smelled another trap, he promised. He telephoned a man named Beto Madrid and asked him to contact Theodoro’s man on the East Coast. Joe was only interested in checking out Theodoro, in confirming his suspicions that it was a government trap, but the next time he heard from Beto was when he called from Colombia. Beto was following through on the deal. Joe told Beto to forget it, but he couldn’t bring himself to tell Jimmy the same thing. Soon the talk escalated from one shipload of marijuana into many, and then into a separate deal to smuggle millions of dollars’ worth of cocaine through Mexico. Jimmy kept demanding to know why Joe was stalling, and Joe kept thinking of new excuses. At one point Joe admitted: “I’ll be honest with you . . . I don’t know what I’m doing.”

Long before the Chagras became seriously worried that Joe was a target in the Wood investigation, they all were worried about Liz. She was falling apart. At one point she was hospitalized for a nervous breakdown, and another time she tried to kill herself on drugs.

Jimmy had always been insanely jealous of Liz, and now that he was helpless behind bars it was almost too much. He’d once accused Liz and Patty of having a lesbian affair. “Because I loaned her a pair of panty hose,” Patty recalled. Another time in Las Vegas, he’d severely beaten Liz, then forced her to admit that she and Joe were lovers. It wasn’t true, but he made Liz telephone the hotel room where Joe and Patty were staying and confess that she’d “told Jimmy the truth” about their affair. “Jimmy was crazy,” Patty said. “You didn’t even try to argue with him.”

During one of her visits to Leavenworth, Liz asked her husband what would happen if Teresa Jasper talked. “If they get [Harrelson’s] daughter to corroborate . . . I’m in trouble,” Liz said.

“You deny everything,” Jimmy told her.

“Well . . . that doesn’t mean shit.”

“Yeah, I know, but . . . how would they know what you’re doing? . . . she didn’t say this is for killing Wood when [she] collected it. . . .”

“No. . . .”

“It could be a gambling debt. It could be anything. . . . What are you nervous about?”

“Nothing. Why?”

“What are you shaking about?” Jimmy asked.

“I shake all the time,” Liz told him.

One time Liz told Jimmy, “There’s a good chance I could go to jail.”

Jimmy replied, “Possibly, honey, but just for ten or fifteen years.”

Later Jimmy reminded his wife that she had insisted on knowing the truth about the Wood killing. In fact, now that he thought about it, she’d told him to do it. “Hey, man, as it stands, you killed Wood,” Jimmy said.

Liz was concerned that her conversations with Jimmy were being taped (it still hadn’t occurred to Joe that everyone’s conversations with Jimmy were being taped), so they sometimes communicated by passing notes. Jimmy had instructed his wife to tear up the notes and flush the pieces down the visitors’ toilet, but when she tried it this time someone had turned off the water. FBI agents recovered 92 soggy pieces and fitted them back together. Among other things, Liz had written, “Joe says the FBI knows I took some money to Teresa.”

On the way back to El Paso, other FBI agents detained Liz—two in Denver, two more at the airport in El Paso. She was badly rattled, but she handled it pretty well. One agent told her, “We got Joe nailed already. We only want the big ones—Joe, Jimmy, and Harrelson.” Liz told Joe and Patty that the agents offered her a deal: $500,000 in cash and a new identity. If she didn’t cooperate, they would take away her children and put her in prison for life. “They told her she had forty-eight hours to make up her mind,” Patty said. Liz replied that she would “think about it.”

In reality, there was nothing to think about. The FBI agents had no intention of working a deal. They believed they had their case. It was contained in many hours of tapes, starting back in October. Shortly after the FBI made its spurious offer, Jimmy was awakened in the dead of night and transferred without explanation to the maximum security prison at Marion, Illinois. For several days no one in the family knew his whereabouts, and for several weeks Joe Chagra wasn’t able to visit his brother.

Soon after Jimmy’s transfer, the FBI took Jerry Ray James out of Leavenworth and hid him in an undisclosed location. A few months later, New Mexico governor Bruce King created a controversy with his astonishing announcement that James had been pardoned. The news that Jerry Ray James had “flipped” sent shock waves through every jailhouse, pool hall, and police precinct from Albuquerque to Corpus Christi. Here was a criminal who had occupied a position on the FBI’s Ten Most Wanted List, who, according to an FBI bulletin, was “extremely dangerous” and fancied himself “a modern-day Al Capone.” The Justice Department claimed James’s release “was in the interest of justice,” but the police chief in Tatum, New Mexico, who had helped send James to prison for what everyone had hoped was the last time, called the pardon “a travesty of justice.” The U.S. attorney in Albuquerque claimed that James had furnished “crucial evidence in an investigation of unique significance to the entire criminal justice system.”

Within days of James’s departure from Leavenworth, the FBI applied to Judge Sessions for permission to search the homes of Joe, Liz, Patsy, and Mom Chagra, and of Red Nichols, Liz Chagra’s father. Though Sessions would probably be trying the Wood murder case, he was able to read sections of transcript from the tapes.

On February 27, 1981, seventy agents from the FBI, the DEA, and the IRS blocked off a section of Santa Anita Street, pulled their vans in place, and raided the five homes. The raid was supposed to be secret, but every media outlet in town knew about it in minutes. The search took fourteen hours. It turned up the map and the tape Joe had made of Harrelson’s incoherent phone call from Houston. It also turned up two ounces of cocaine and five pounds of marijuana. Agents seized family assets, including several million dollars’ worth of jewelry and silver coins, thousands in cash, and other valuables. They confiscated five of Mom Chagra’s scrapbooks. They even took a ring that Patty’s parents had given her when she was in high school. In theory, all these assets were seized as a lien against the $600,000 Jimmy owed the IRS, even though the IRS had already collected $450,000 from the sale of the house in Vegas and another $180,000 that Jimmy was carrying when he was arrested, plus a car and a $35,000 Winnebago.

“I Thought You’d Hire the Mafia”

Joe Chagra and his attorney Billy Ravkind first learned of the existence of the tapes on March 23, 1981, during a five-hour interview with the FBI. An agent asked Joe if he’d ever admitted to anyone any part in Wood’s murder. Joe said he had not. The agent raised an eyebrow, then played a short piece of tape. Joe sat stunned as he heard his own voice during this exchange with his brother:

JIMMY: Boy, we shouldn’t of done that, huh, Joe?

JOE: That’s right.

JIMMY: You’re the one that said do it, do it, do it.

At this point the agent switched off the tape machine. Joe could feel the cold, sickening swirl of cocaine in his head as he fumbled for words. Yes, he remembered now. He was horrified that Jimmy would say something like that, even as a joke. The agents smiled. They had planted the trap carefully, and now it was time to spring it. They played another short burst of tape:

JIMMY: You’re the one was all hot to do it.

JOE: . . . I never thought you’d get someone like this guy [Harrelson] to do it. . . . I always thought . . . someone in the Mafia.

JIMMY: I had a few thoughts like that. What difference does it make?

JOE: Well, this guy’s an asshole. That’s what difference.

The agents told Ravkind that they had hours of taped conversations in which Jimmy and Joe discussed past and present crimes and planned future ones, including jailbreaks and narcotics trafficking. Maybe Joe was joking, maybe he wasn’t. That would be a question for the jury to decide.

“I don’t believe they really want to indict Joe,” Ravkind said. “But they feel they don’t have a choice. That may be the only way they can use the tapes. Joe can’t waive attorney-client privilege, even if he wants to: only his clients have that power. The only way they can get around the privilege is by claiming Joe was part of the conspiracy.”

At this point Ravkind took some calculated risks. First, he told reporters about the incriminating piece of tape he’d heard in the FBI office. By taking the initiative, he believed, he could disarm the government’s bomb. Ravkind then arranged for his client to take a polygraph test. Joe passed on the question of Wood’s murder. Later, the FBI agreed to test him. Joe failed on two questions, one concerning the validity of his attorney-client claim with Harrelson, the other his knowledge of the whereabouts of the gun. Still, the government agents seemed inclined to make a deal. At one point they offered Joe five to ten years’ prison time for a guilty plea and cooperation. They even discussed restoring his license to practice law once he’d served time. Joe discussed the offer with Patty and they refused it. “Joe couldn’t confess to something he didn’t do,” Patty said. “If they’d limited the charge to possession of drugs, we would have gone for it. But he couldn’t confess to conspiring to kill Wood or to obstruction of justice.”

In August 1981 twenty agents excavated a creek bed near Lake Ray Hubbard. All they got was blisters. During a second search, they trucked in loads of sand, dammed up the creek bed, and used two backhoes to dig out the mud, which they sifted by hand. Again they found nothing. The break came a few weeks later when two boys walking along the creek found a stock from what turned out to be a .240-caliber Weatherby Mark V rifle. For more than two years the FBI had been looking for the wrong gun.

But now they moved quickly. The manufacturer of the rifle, Weatherby, Inc., of South Gate, California, furnished a list of dealers. Agents checked each dealer’s records until they turned up a purchaser who had used a nonexistent phone number and address. The name on the form was Fay King. Faking! Using fingerprints, agents traced the purchase to Jo Ann Harrelson. In November the wife of the suspected hit man was found guilty of using a false name to purchase a weapon; she was sentenced to three years in prison.

In December Harrelson pleaded no contest to drug and weapons charges stemming from his escapade near Van Horn. He was sentenced to forty years (he was already doing thirty on his earlier conviction in Houston). The FBI finally had Harrelson where it wanted him—in a Texas prison, chopping cotton. The squeeze was on.

Teresa Starr Jasper, Harrelson’s stepdaughter, was also in jail for refusing to testify before the grand jury. After weeks in jail, she finally agreed to talk in exchange for a grant of immunity.

The investigation ended on April 15, 1982, almost three years after it had begun. Indictments charging conspiracy to murder Judge Wood were returned against Jimmy, Liz, and Joe Chagra, and Charles Harrelson. They, as well as Jo Ann Harrelson, were also charged with a number of other crimes. The cost had been incredible. Seventy full-time FBI agents had logged 82,000 man-hours and interviewed 30,000 people. And that didn’t include work done by the DEA, the IRS, and other government agencies. The investigation had cost at least $5 million, maybe as much as $10 million. New and frightening areas of electronic surveillance had been explored, and pardons or immunity had been granted to dozens of criminals, one of them a boss dope smuggler and another a man who thought of himself as a modern-day Al Capone.

The five defendants remain in jail pending trial on September 28.

- More About:

- TM Classics

- Longreads

- San Antonio