One of the few things thirteen-year-old McKenzie Mullins likes more than squeezing a horse’s nose is messing with its lower lip. “It’s all about the lip,” she told me one morning last summer, standing in her family’s stables, in Gordon, which house seventy horses, including Twister, Swingin’, Bully, Fancy, Player, Lizzie, Plagiarism, and Snoopy. When we’d arrived, McKenzie had hopped up onto a fence and waved to the horses with the enthusiasm of somebody entering a giant family reunion. “Hello, Gordo!” she yelled. Gordo looked up and shook his mane. “Hey, Earless!” she yelled to another one. “That’s Earless Arless. He likes to have his ears scratched.” Then she tiptoed up to a horse that was falling asleep—one leg bent, its big face relaxed, its lower lip beginning to sag and quiver. She reached up, tugged on its lip, and the horse twisted its face like an annoyed Mr. Ed. McKenzie giggled hysterically.

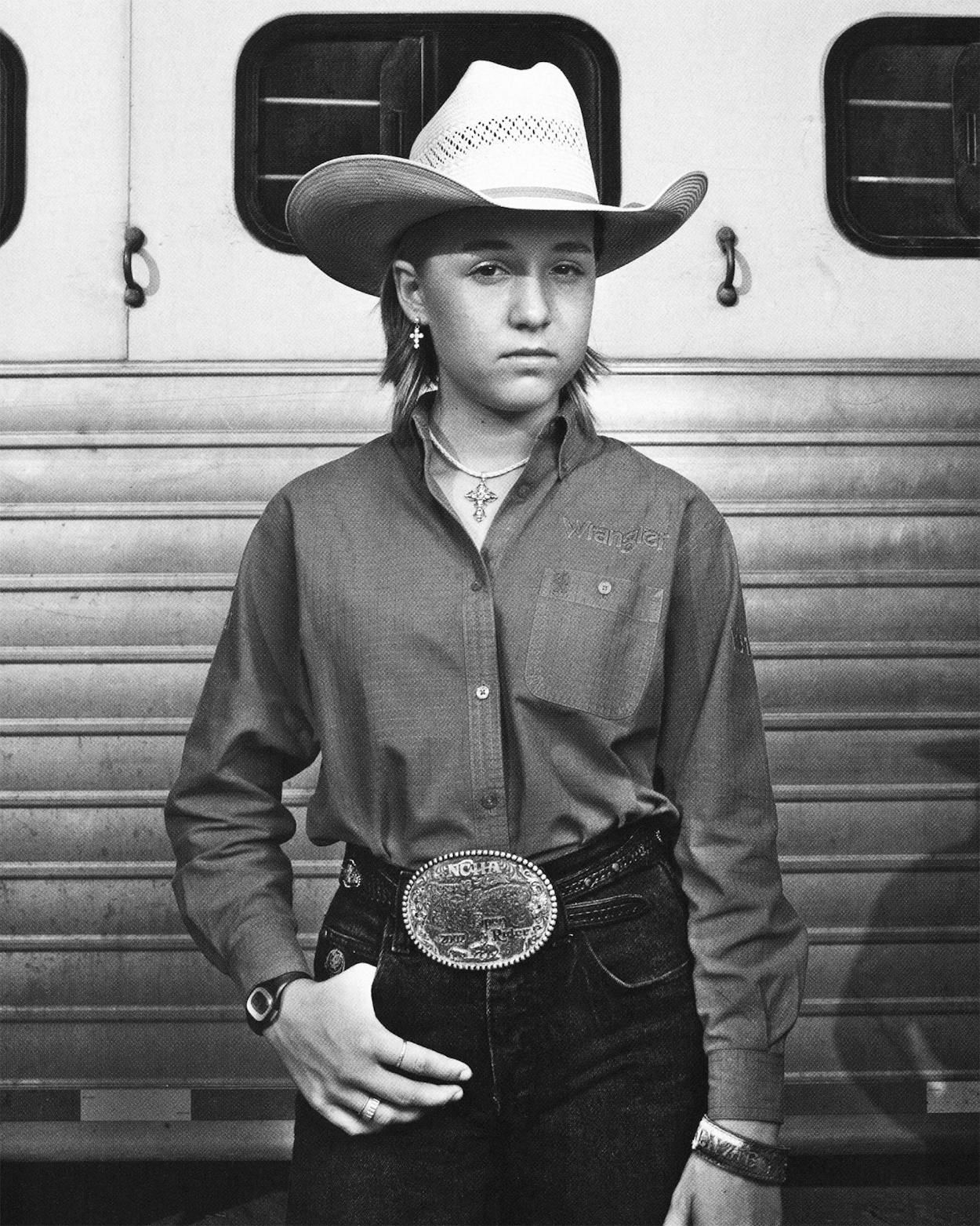

Seeing this, it is easy to forget that McKenzie Mullins is one of the greatest cowgirls in the world. Physically she is slight. She stands five-feet-three, weighs 95 pounds, and wears size 0 slim jeans. Pink rubber bands cover her braces, and her freckled cheeks retain a ten-year-old’s plumpness. But last year, at the end of the 2002 season, McKenzie became the youngest competitor ever to enter the open division of the National Cutting Horse Association (NCHA) World Championship Finals—the Super Bowl of cutting. Taking second place, she beat out her sixty-year-old stepfather, Robert Rust, a two-time world champion and NCHA hall of famer, as well as several men four times her age with barrel chests and Clint Eastwood squints who could probably bench-press her with one arm. This season she has continued her streak, maintaining second place on an otherwise adult-dominated circuit, and this month, she will compete again in the World Finals, in Amarillo.

To compete at such a high level, McKenzie is on the road nearly 250 days out of the year, and she has forfeited childhood as we normally conceive of it: She earns enough money that she could live on her own if she wanted (she has a sponsorship contract with Wrangler to wear its clothes in the arena, and so far this season she has pulled in more than $53,000 in prize money); rather than attend school, she squeezes in homeschool lessons; and in place of passive greetings, she often responds to routine questions like “How are you doing?” with a ranking number. She can act remarkably mature—such as when she strokes her chin and discusses the finer points of taking a horse to stud—and since she’s often on the road, McKenzie spends more time with her parents than most adolescents would tolerate. In fact, of all the people she knows, she says her stepfather is the coolest.

Together with Robert, who is considered one of the top cutting-horse trainers in the world, and her mother, Connie, a former ballet dancer, McKenzie logs between 40,000 to 80,000 miles a year in the family’s red Freightliner truck on the way to and from cutting competitions. At these events, from morning to night, she is either feeding, washing, riding, or competing on a horse. It may be a hard life, but to hear McKenzie tell it, she wouldn’t have it any other way. “I couldn’t sit very long at a desk,” she says, “and I don’t ever want to live in a city. I love traveling and watching the scenery from the truck.” She’ll grudgingly acknowledge that she works harder than most kids, but she says she enjoys the rewards of a less normal life. For now, McKenzie doesn’t feel as though she’s missing out on anything, really. All she wants is to be the best, and her proximity to greatness is so intoxicating that the alternatives seem dull.

In contrast to most cowboy disciplines, cutting requires more instinct than athleticism or brute strength. There is no tackling or roping. There is no riding of animals whose genitals are strung up and yanked to make them buck. Instead, competitors are judged on a scale of 60 to 80 for their ability to separate at least two cows, one at a time, from a small herd in two and a half minutes. Sounds easy, but once a competitor separates a cow (in the sport, both steers and heifers are referred to as “cows”), she must sit between it and the herd, facing down her opponent like a linebacker does a running back. So strong is the cow’s instinct to rejoin its herd that when isolated, it will sometimes pee, spew snot, and run like hell—often charging the horse and rider—to try to get back with the group.

It’s fitting, then, that the highest compliment a cutting competitor can receive is to be told that he or she “has cow.” Having cow (not to be confused with “having a cow”) means that you are an expert in reading bovine body language. You are able to interpret a cow’s tail angles and twitches and head twists and gait changes, all of which can help you anticipate when it wants to go right or left, when it is getting mad, when it is about to charge, and when it is ready to give up. Most important, having cow means you can maneuver a thousand-pound horse to cut a cow off no matter how hard it tries to fake you out or how intent it seems on knocking you over. “You’ve got to know where it’s going next,” says Robert, “and some people can do that better than others.”

It was Robert who first discovered that McKenzie had cow. Four years ago she mostly refused to get near horses. She was afraid to ride and showed little interest in taking part in the profession of her new stepfather. But one day, after her mom had left for a ten-day vacation, McKenzie came out of the house from lunch to clean the stalls, and Robert stopped her on the barn’s cement porch, where the family saddles the horses.

“If you’re going to live in my family,” he told her, “you’re going to learn to ride.”

“Mama said I can do it when I’m ready,” she replied.

“Well, Mama’s not here,” he said.

That afternoon they went to the stables together. Her arms were too little to throw the saddle on the horse, so Robert set up the tack and hoisted her up. “I was scared,” she says. “I really didn’t like horses. They were so big.” But after two days of loping in the family’s practice arena, Robert brought in some cattle from one of their back pastures and coached her as she tried to cut a cow off. “Block its line of vision,” he told her. “Stay in front like you’re playing soccer and somebody’s headed for your goal.” But McKenzie just felt out of control. “I’d tell that to Robert,” she says. “ ’I can’t do this,’ I’d say, and he’d say, ‘You’re going to do it.’ ”

Over the following week, with Robert coaxing her, she began to relax and move with the horse. She pushed her sixty pounds onto its back and learned to hold a steady posture. Soon she was going to bed and dreaming of riding again. “It was the first thing I wanted to do in the morning,” she says. “A few days before my mom came home, I remember breaking the horse out into a run in the pasture. I felt free.”

“When I came back she was a totally different person,” says Connie. The dinner-table conversations that had always seemed a little boring to McKenzie finally took on meaning. She listened and asked questions and for the first time caught a glimpse of what she might be capable of. “Her confidence went up that first summer because she decided she wanted this,” says Robert. “If we had kept pushing her, it wouldn’t have happened.”

After her first competition, that summer, McKenzie rose steadily in the competitive cutting circuit during the next three years. In 2000 she won tenth place in the junior youth division. In 2001 she took third in the youth. But last season was her breakthrough. Heading to the championship finals in February 2003, Robert could have chosen any of his colleagues to show one of his best cutting horses, Rosie’s Lena, in the open division. Despite her age and inexperience, he chose McKenzie. He says people asked him, “ ’Don’t you think you’re putting a lot of pressure on her?’

And I said, ‘You learn to deal with pressure whether you’re twelve or forty.’ We told her to go and have fun. We said first is fine, but second is fine too. It’s different when these guys are older and this money is paying the light bill.”

Still, there were 8,500 people packed into the stands. “I was so nervous before I went into the arena,” says McKenzie. “It felt like everybody was watching me and thinking, ‘There’s the youngest.’ But I felt like I was watching it from some other place. I couldn’t hear anything. It was like I was in a bubble.” You wouldn’t have perceived she was nervous from the way she performed unless you knew that the stone-still expression she wore entering the ring was one of shock. By the end of the competition, she had narrowly missed first place. McKenzie sums up her performance this way: “I was trying to remember to breathe.”

Last August McKenzie and her family traveled to Austin for a cutting competition at the Travis County Exposition Center. It was a low-stakes event, but McKenzie’s performance and the money she earned would factor into her season-long ranking (only cutters ranked in the top fifty can enter the World Finals). This season, while she remains in second place, the number one ranking is being fiercely guarded by a petite grandmother named Mary Jo Milner, a five-time world champ in the non-pro circuit who wants to break a world record with a sixth win.

Inside the corrugated-metal venue, the temperature was 98 degrees, and a slight breeze blew the apple-sweet smell of fresh dirt through the building’s open sides. About thirty people wriggled uncomfortably on the metal bleachers that faced the basketball-court-size ring; a dozen others plopped down a cooler of sodas in the middle of a circle of folding chairs at floor level and discussed families, sports, and the latest news from Cutting Horse Chatter magazine.

When it was McKenzie’s turn to cut, she rode into the ring dressed in a pink plaid shirt, a white straw hat, and jeans covered by chaps. On her belt was the 2002 runner-up world championship buckle—a gold-colored disk as big as a mango that pictured a horse and a cow head-to-head in poses suggesting debutante dips. On the far side of the ring, a group of about twenty yearlings huddled together side by side against the arena’s back fence, rears facing McKenzie.

Riding her horse Fancy, McKenzie entered the herd, and the cows responded by trotting into the middle of the ring. A couple seconds later, she selected a black cow and cut it off. The cow’s big ears flopped and its eyes widened as it realized it was alone, and it began to sprint back and forth. For thirty seconds, McKenzie, eyes half-closed, countered every juke the cow threw at her while folks in the bleachers cheered, “Here, cow!” and “Haw!” Finally, having displayed her control, McKenzie released cow number one with 1:23 left on the clock. Her dispatched opponent, looking baffled and pitiful, trotted back to the group.

At the 53-second mark, McKenzie made a deep cut, selecting a cow from the middle of the herd; this strategy scores more points from the judges because it is more difficult. The cow she’d chosen was feistier, and it headed directly at her and Fancy. But McKenzie just toyed with it, tapping Fancy with her boots, prompting him to plunge deeply into the soft dirt as he dodged left, then right. McKenzie kept a perfectly balletic posture, eyeing the dazed bovine with her hat tilted down.

“Haw!” came from the bleachers. “Here, cow!” With about half a minute left, she let the second cow go and then spent her last ten seconds toying with a brown-and-white cow. When the buzzer rang, she patted her horse and pushed her hat down on her head. The judge announced her score—76, four points from perfect and enough to secure McKenzie first place in the day’s event.

Debbie Patterson, a three-time world champ in the non-pro circuit told me later, “The thing about McKenzie is she works harder at this than just about anybody, all year round. That’s what it takes. That little girl eats, sleeps, and breathes cutting.”

Anyone who spends time with McKenzie will quickly understand just how focused she is. One afternoon, she gave me a tour of her family’s house, in Gordon, about seventy miles southwest of Fort Worth. It’s a three-bedroom, two-bath manufactured home facing the family’s huge new cutting arena and surrounded by 480 acres. Along the way, McKenzie stopped to point out the wall of photographs showing her and Robert in various cutting competitions, the saddle she won in the 2002 World Finals, and the glass-top table displaying about sixty belt-buckle awards. In her bedroom, which was striped with light green and purple paint, was a suitable menagerie of plastic ponies. McKenzie went into her closet and showed me one of her twenty Wrangler shirts and the Wrangler jeans she was going to wear the next day. Then she dragged a book off her shelf called FunFax Horse and Pony and began reading.

“ ’Surprising fact: A horse’s brain weighs approximately 650 grams.’ ” She stuck her lip out and nodded, impressed. “ ’Heaviest: In 1938, in Iowa, Brooklyn Supreme, a Belgian Brabant, weighed 1.44 tons.’ Wo-o-w. ‘Longest mane: American horse Maude’s mane grew to 5.5 meters, or 18 feet. Smallest: Little Pumpkin, an American Falabella stallion, stood 35.5 centimeters, or 14 inches.’ ” She placed her hand a foot from the floor, her brown eyes wide. “Hey, that’s really short!”

It’s no wonder McKenzie has such a singular focus. On a typical day at home, she wakes up at seven-thirty and does schoolwork with her mom. Just before noon she walks over to the family’s 120- by 200-foot arena. There, where a radio tuned to old country plays 24 hours a day, she’ll hook the young horses up to a guided walking circle that squeaks as it goes around. After that she might spend half an hour galloping through the 355-acre woods to check on the new colts, and on her way back, she’ll take twenty minutes to coax a few skittish cows or buffalo into the arena for horse training. For the remainder of the afternoon and evening she helps Robert teach the young or inexperienced cutting horses, reading cows till the sun goes down. Then she gets to eat, watch a little TV, and finally, sleep.

But that’s just when she’s home. The family’s hauling schedule shows that three or four days out of each week, from December to the following November, they’re traveling to compete in places like Virginia, Mississippi, Oklahoma—anywhere there is a cutting event. They drive all day to get to a place, often arriving late at night, and then lead about ten horses out of their hauling trailer, set them up in stalls, and feed them each a bucket of alfalfa hay. Sometimes McKenzie will go to bed around two o’clock in the morning at a nearby motel, then wake up at five, feed the horses by six, and start warming up by seven or eight. Most nights the cuttings finish between eight and eleven o’clock, though if McKenzie’s events end early, her folks usually let her visit with any young kids who are hanging around. On the ride home, she curls up in a bunk bed installed in the truck.

It’s a schedule that means McKenzie’s contact with the world outside cutting horses is often limited to the little television in the truck’s cab. She watches, amazed by some of the things she sees, like tattoos, men with long hair, or people who surgically split their tongues in half like a lizard’s. She tries to stay tuned in through her old friends from school. She sends them text messages and sleeps over at girls’ houses whenever she can, dissecting the various dating strategies of those who have more day-to-day socialization. “My friends and I decided that all of us have to approve if we want to date somebody,” she says. “We have to tell each other who he is, and we can’t leave each other out.” And McKenzie is no slouch when it comes to giving advice. Her friend Elizabeth, age fifteen, says, “McKenzie helps me with my boy problems; I help her with hers.” But even cutting-horse friends like Elizabeth inhabit a different terrain: Elizabeth attends a private high school in Fort Worth and is a cheerleader. For her, cutting is still a weekend pursuit, not a career.

Once in a while, McKenzie sits in the arena and imagines her future. Years from now she believes she will go to college and become a veterinarian. Until then, she’ll be far from desks and teachers and young peers, learning about life while riding back and forth and back and forth in a red Freightliner truck and on the saddle of a horse. But her focus has given her the ability to magnify her world’s elements, and she’s old enough now that she sees her life sharply, at least in the way it contrasts with the lives of some of her peers. “To me, the country kids learn how to work earlier than city kids. One of my friends who’s nine woke up at six this morning to clean stalls,” she said. And what someone else might consider a tough lifestyle McKenzie sees as slow-paced, one that allows her the long hours to spend time with her family. “Everybody in the city is in a rush,” she said. “They don’t see their fathers. When the dad gets home, he’s irritated and wants to go to bed.”

On my last visit with McKenzie, I went with the family to the Silverado Arena, in the town of Weatherford, one of the cutting community’s favorite venues. A structure about half as big as a Home Depot, the place has the feel of a country club. Wood benches surround the ring, large ceiling fans keep the air from getting stale, the pen has a fresh coat of kelly-green paint, and a glass-enclosed restaurant with a view of the action sits on the second floor. McKenzie and her parents like the Silverado because it’s only an hour from home but also because, compared with some of the dilapidated outdoor arenas they visit during the season, the place is a palace.

Which is somewhat surprising. You can’t find many sports with wealthier contestants than cutting. Nationally, more than nine thousand NCHA members compete in cuttings throughout the season, making $1,000 to $30,000 per weekend. So far this season Robert has made more than $1 million. Much of that income, however, goes back into the horses, which can cost up to $1 million to purchase and $800 a month to care for. (Last season, the only thing McKenzie bought with her winnings—which totaled $17,400—was a $72 salmon-colored shirt decorated with small flowers. The rest went back into the horses.)

Inside the Silverado, the family began pointing out some of their moneyed competitors: Lonnie Allsup, of Allsup convenience stores, was there, as was Jerry Durant, of Durant Chevrolet, and one couple who controls three million acres of timberland in Canada. In the stands, I met Wal-Mart heiress Alice Walton, one of the richest women in the world. She knew all about McKenzie. She pointed at the arena with a long brown cigarette and explained, “This is a mind game. McKenzie is good at it. Lots of kids are good at it. But you’ve seen what she can do. She has cow.”

When it was McKenzie’s turn to compete, she rode confidently into the arena atop Fancy and tucked her loose hair behind her ears. Fancy walked steadily as McKenzie picked a cow out of the wall of rears and prodded it into the center of the arena. Then the jumping dance began. She finished with a score of 72.

It was Friday night, and with the competition so close to home, Robert, Connie, and McKenzie had the luxury of driving back to Gordon (population: 451) in search of dinner. On the way, the sappy Lonestar country song “My Front Porch Looking In” played on the radio.

“Oh, I like this one. Turn it up,” McKenzie said.

Instead, Robert, who was driving, turned the radio off.

McKenzie punched him in the arm and pleaded with her mom, “Make him turn it on!”

Connie smirked, raised an eyebrow, and continued to look ahead.

McKenzie proceeded to punch Robert in the arm repeatedly until he threw his head back and laughed a high-pitched “Hee, hee!” and said, “Aw, McKenzie, this old country boy is so sad I think I’m going to have to pull over onto the side of the road an’ cry.”

McKenzie quit slugging him, and she sat back in her seat and folded her arms, trying to contain an amused smile.

Rounding the corner into town, the family passed the high school McKenzie would be attending if she spent less time on the road. The school itself was difficult to identify among all the manufactured buildings.

“Where is it?” Robert asked.

When McKenzie pointed it out, Robert slowed the truck down and the three of them looked at the school in silence, as if they were observing an exotic species in too small a cage. Then Robert picked up speed and headed back down the road.